FALL 2023 VOLUME 69 NUMBER 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF

THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Art

in the

Botanical

Sciences

Applications in Plant

Sciences

Celebrates Its 10th

Anniversary... p. 252

Botanical Society of America’s Award

Winners... p. 244

Fall 2023 Volume 69 Number 3

FROM the EDITOR

Greetings,

I am thrilled to share this very special issue of PSB that focuses on the many connections

between science and art. This issue has been brought to you by an impressive team of guest

editors: Patricia Chan, Rosemary Glos, Ashley Hamersma, Kasey Pham, and Nicolette

Sipperly. I want to thank this team for their creative visioning and hard work putting this

issue together. I also want to thank the talented authors and creators who have shared their

work with us. There was such a positive response to the call for articles on this topic that we

anticipate continuing this subject in our Spring and Summer issues.

In this issue, you will also find many of our regular PSB sections, as well as news and awards

from Botany 2023 and profiles of our new Distinguished Fellows.

Sincerely,

PSB 69 (3) 2023

159

159

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SPECIAL SECTION: ARTS IN THE BOTANICAL SCIENCES: PAST, PRESENT,

AND FUTURE................................................................................................................................

161

Weaving Together Culture and Ecology to Express My Identity as a Scientist

(by Clarissa Rodriguez)......................................................................................................................... 162

Art in the Herbarium? (by Maura Flannery)....................................................................................... 165

The Significance of Illustrations as Nomenclatural Types in Botany: “Iconotypes”

at the Natural History Museum Vienna and the Importance of Color Systems,

such as Those Utilized by Ferdinand Bauer [1760–1826]

(by Tanja M. Schuster et al.)............................................................................................................... 170

Celebrating the Launch of the UTEP Virtual Herbarium by Highlighting

Contemporary and Historical Art and Science of the El Paso Region

(Mingna V. Zhuang et al.)..................................................................................................................... 176

Celebrating Plant Diversity through Art (by Alice V. Pierce et al.) ........................................ 179

Brazilian Botanists Flirting with Arts: Valuing the Multicultural Heritage

(by Lucas C. Marinho et al.) ................................................................................................................ 182

Integrating Botany, History, Culture, and Contemporary Art in a Botanical Garden

Museum (by Nezka Pfeifer)............................................................................................................... 186

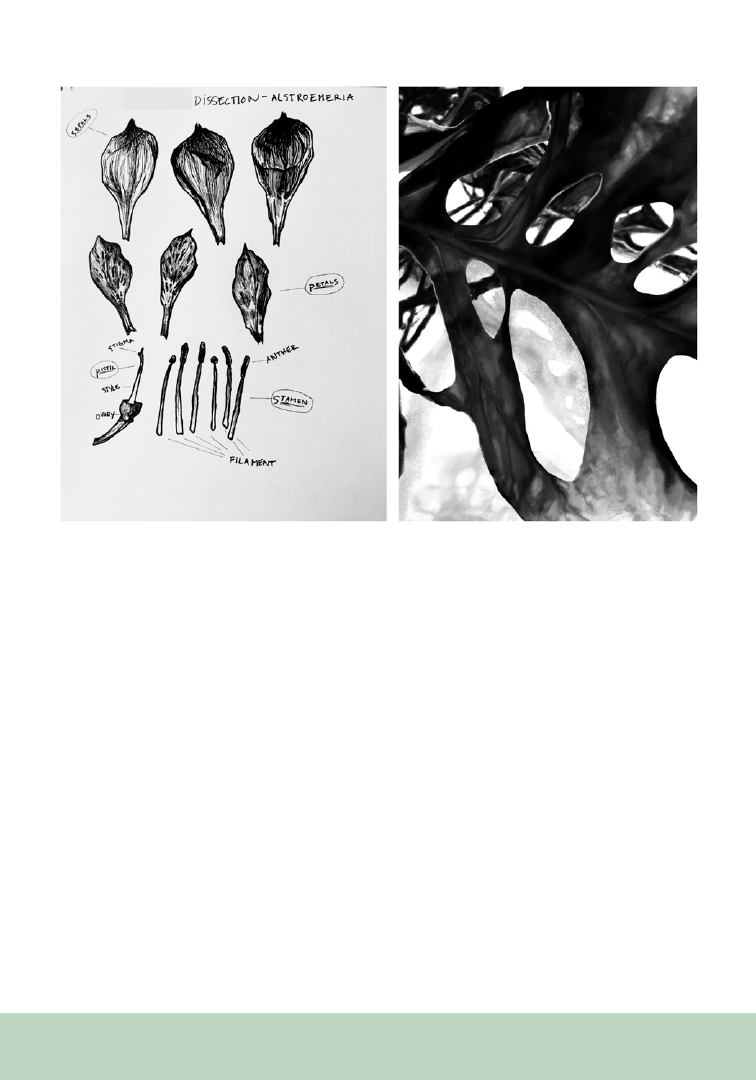

Science, Art, and the Allure of Photographs (by Benjamin-Goulet-Scott

and Jacob Suissa).................................................................................................................................... 189

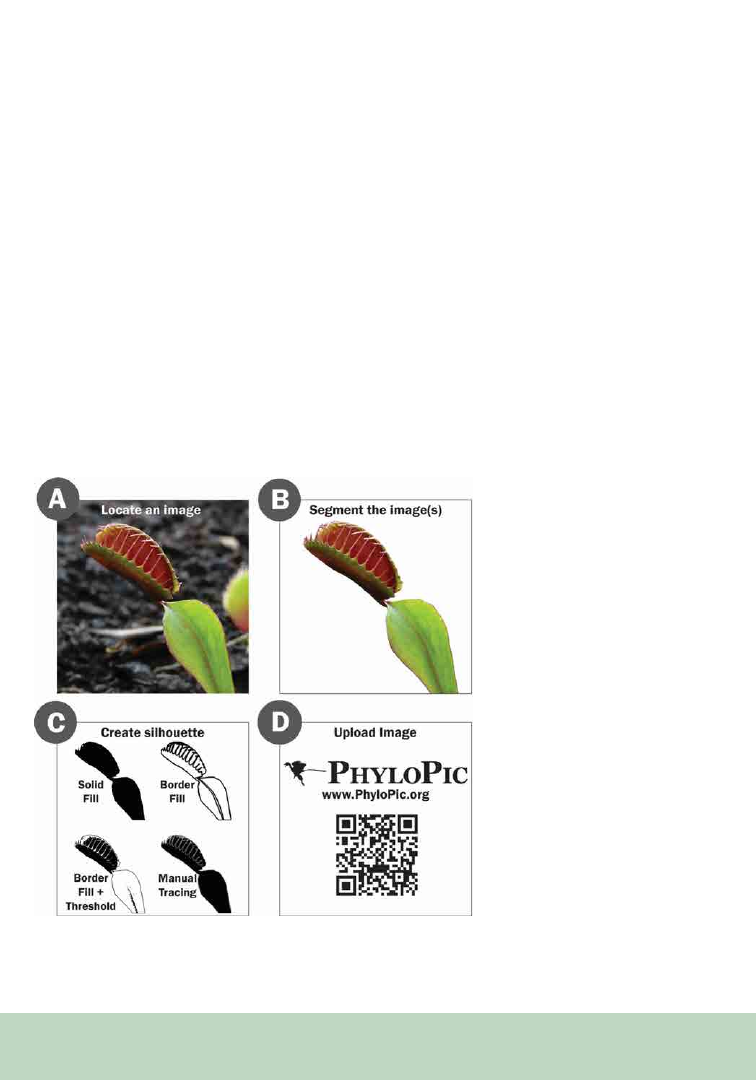

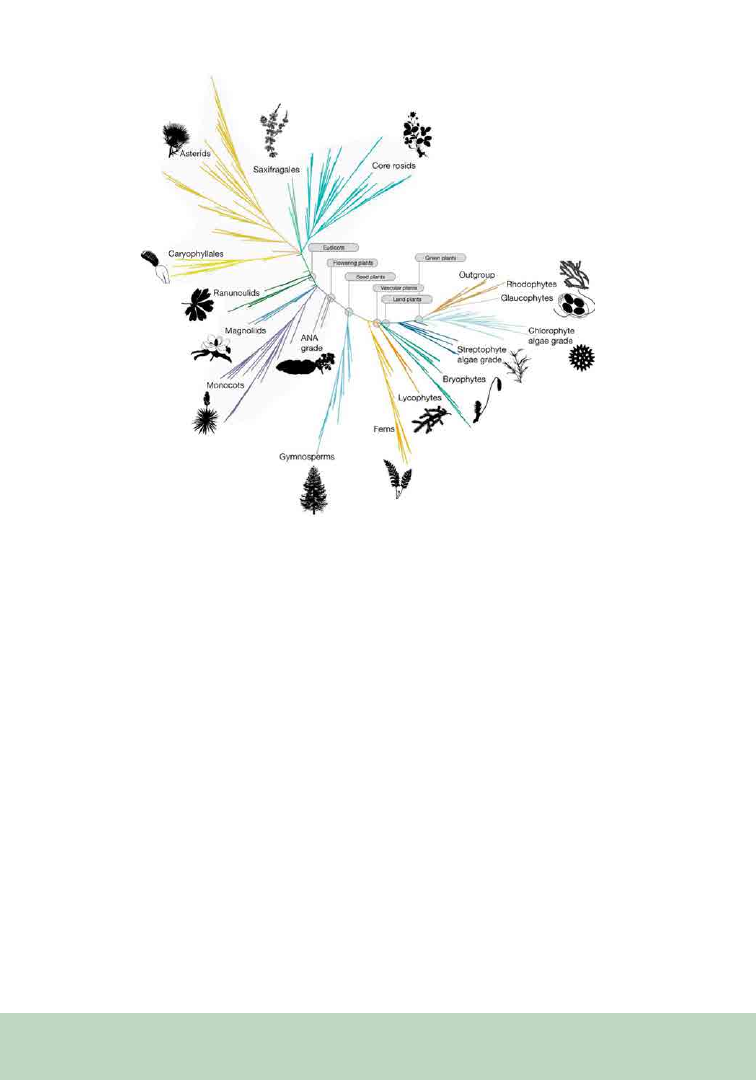

Filling Out PhyloPic: Call for Adoption by Plant Scientists (by Mason C. McNair

and T. Michael Keesey)......................................................................................................................... 193

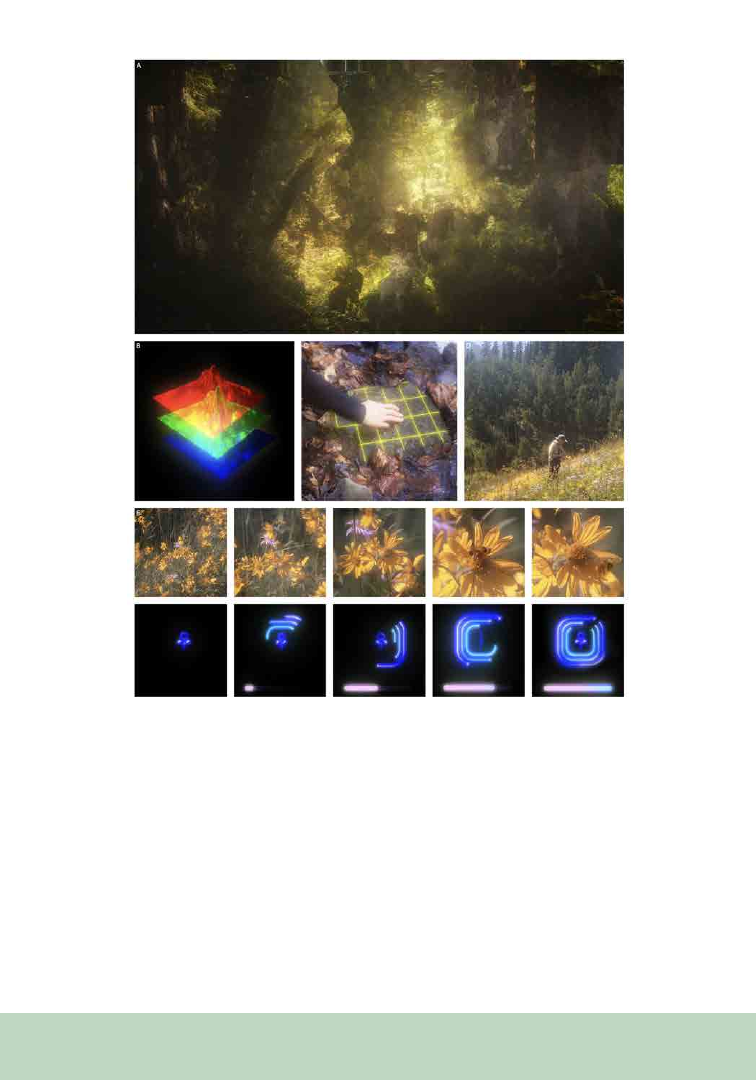

Can the Collaboration of Science and Art Broaden Our Understanding of Nature?

(by Paul J. CaraDonna and Mark Dorf) ........................................................................................ 198

The Integration of Botanical Science, Art, and Agency (by Maria Park et al.)................ 202

“Art of Horticulture” Course Cultivates Creativity (by Emily Detrick

and Craig Cramer..................................................................................................................................... 206

Reaching Across Audiences: Connecting to and Communicating Botanical Concepts

Through Art (by Janette L. Davidson et al.) .............................................................................. 209

Reconnecting Science with the Visual Arts: Teaching the Art of Biology

(by Lynne Gildensoph) .......................................................................................................................... 216

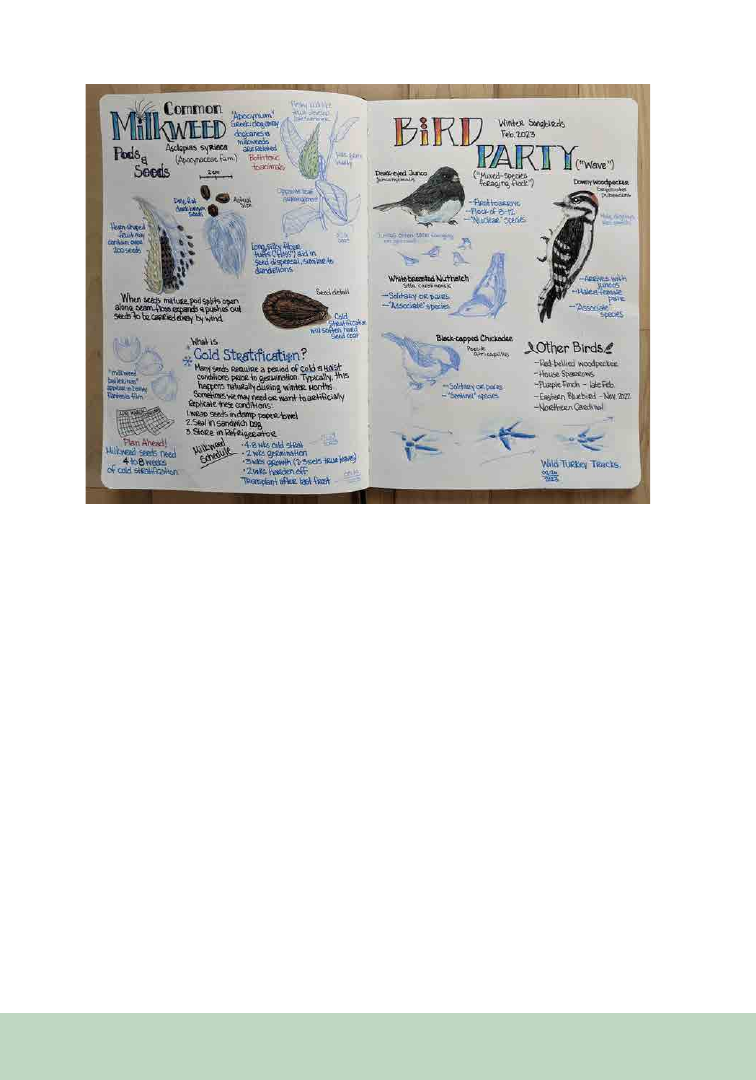

Nature Journaling: Sharing Perspectives Between Art and Science

(by Corinn Rutkoski et al.).................................................................................................................... 219

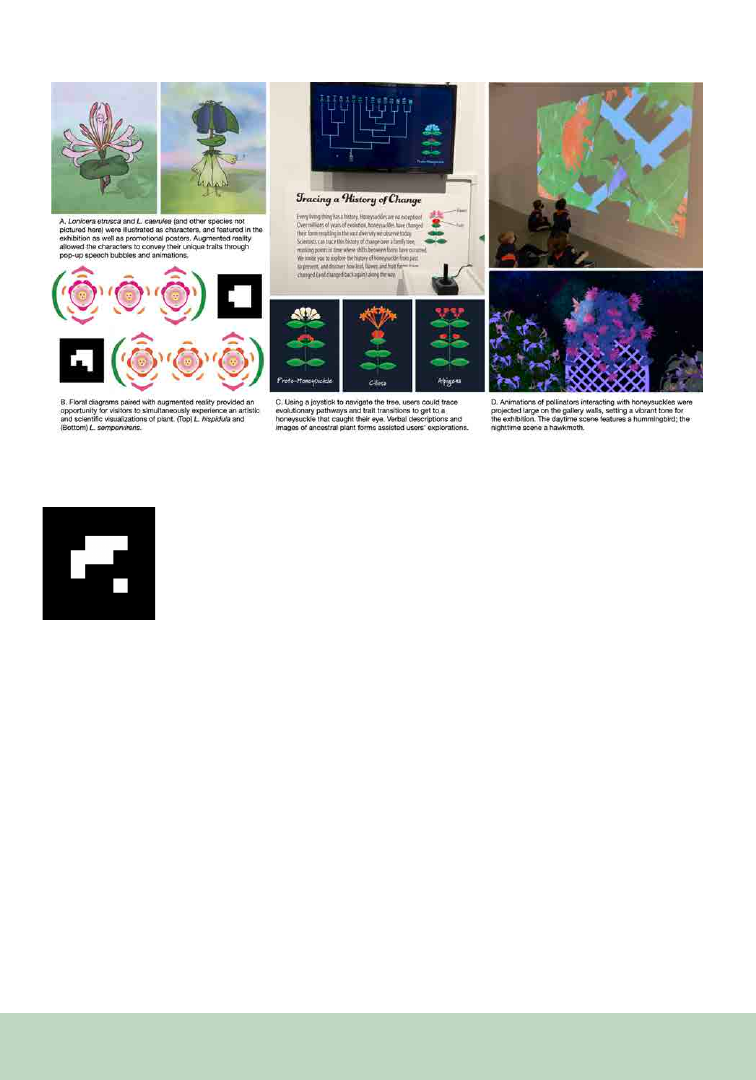

Plants as a Case for Creative Collaboration: Designing the Interactive Art-Science

Exhibition Meaningful Beauty (by Christopher Ault et al.) ................................................ 221

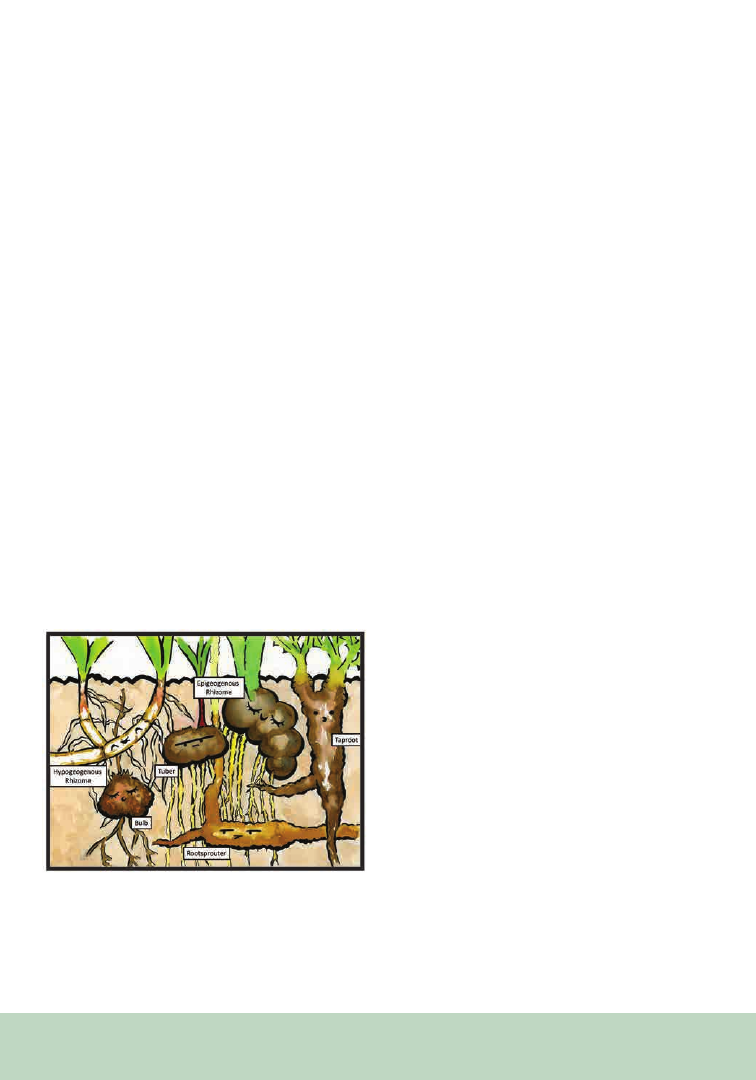

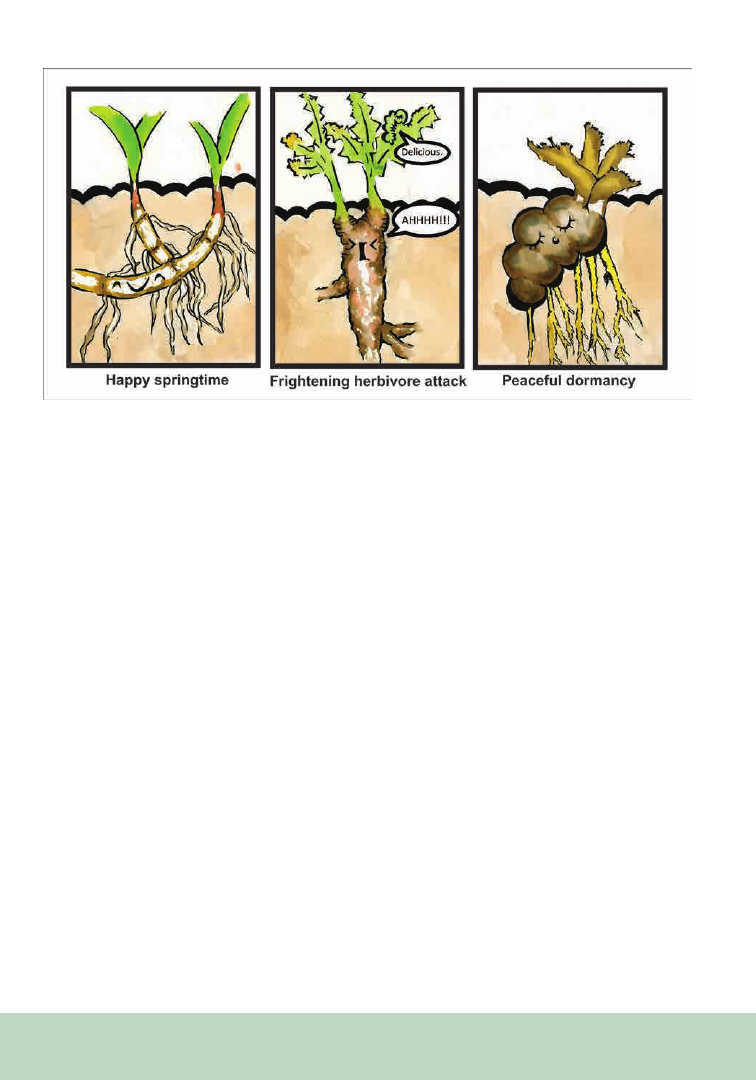

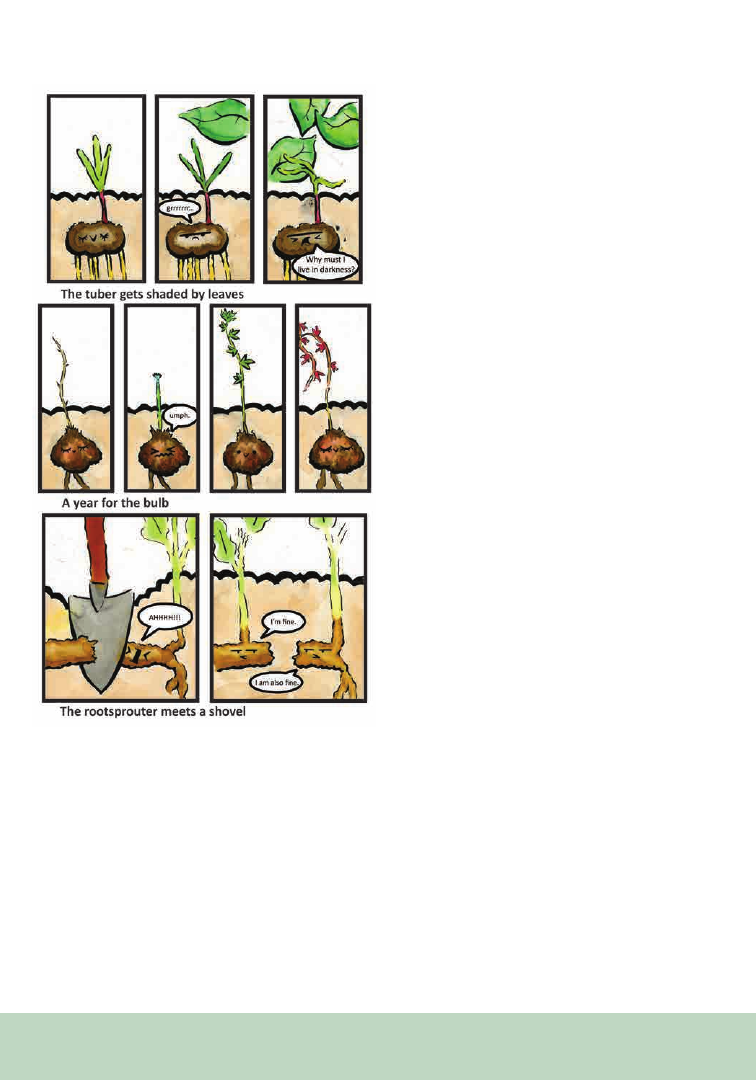

Understanding Plants Through Imagery: Functional Traits, Cuteness, and

Narrative (by F. Curtis Lubbe) .......................................................................................................... 227

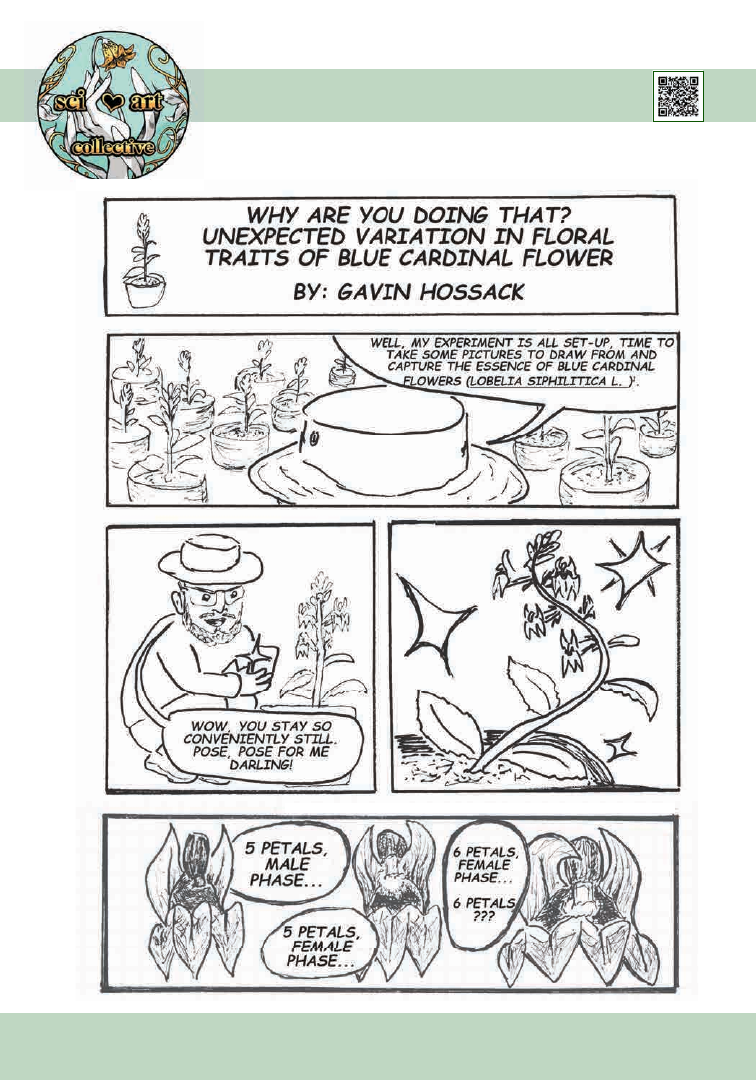

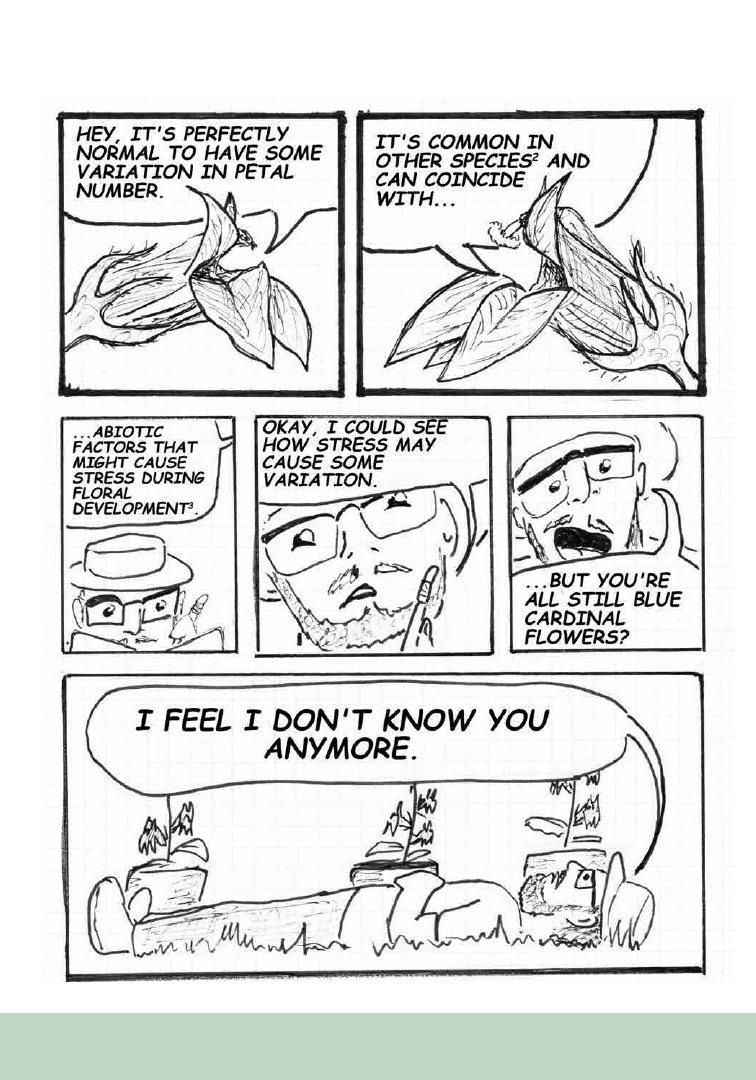

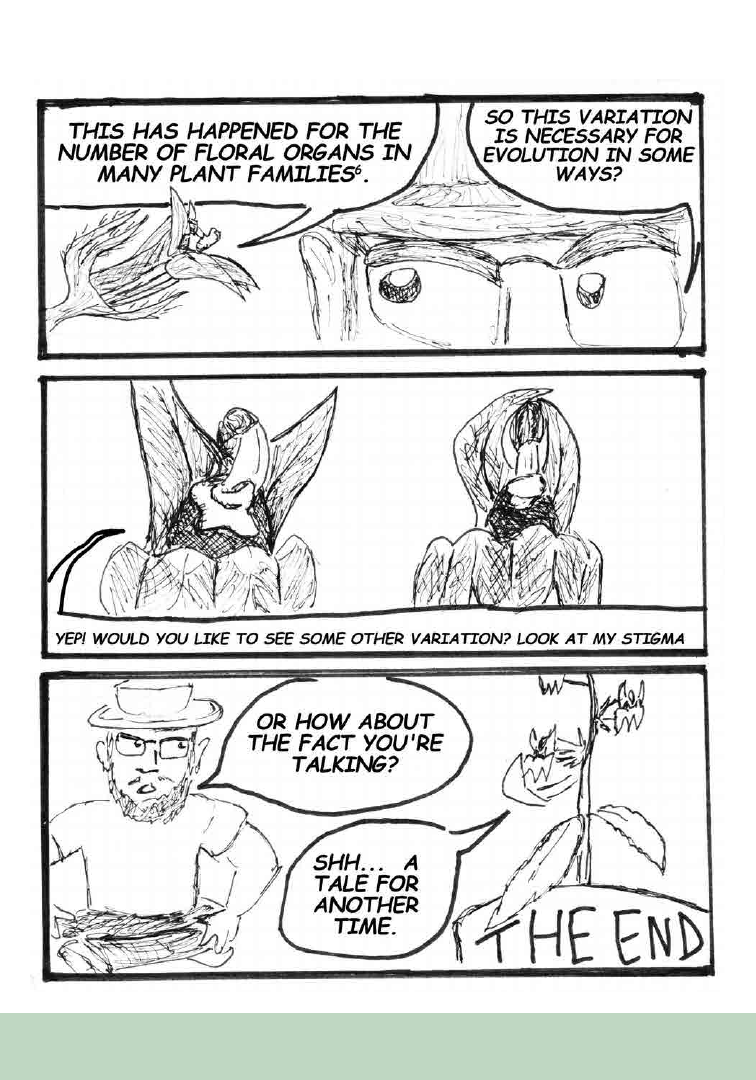

Why Are You Doing That? Unexpected Varaition in Floral Traits of

Blue Cardinal Flower (by Gavin Hossack).................................................................................. 232

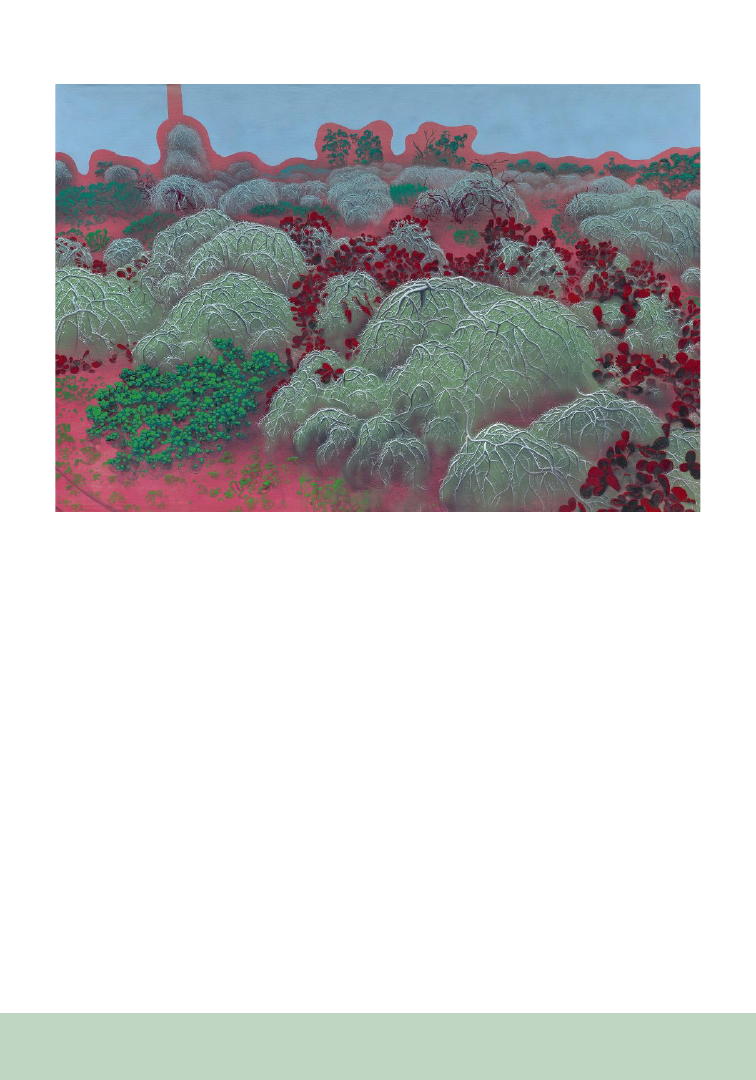

Wild Growth Paintings (by Daniel Philosoph)................................................................................... 237

Art + Botany: Making a Difference (by Kathleen Marie Garness) ......................................... 239

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN: FALL 2023

..............................................................................................244

SOCIETY NEWS

Botanical Society of America’s Award Winners (Part 2) ........................................................................244

Publications Corner..................................................................................................................................................... 252

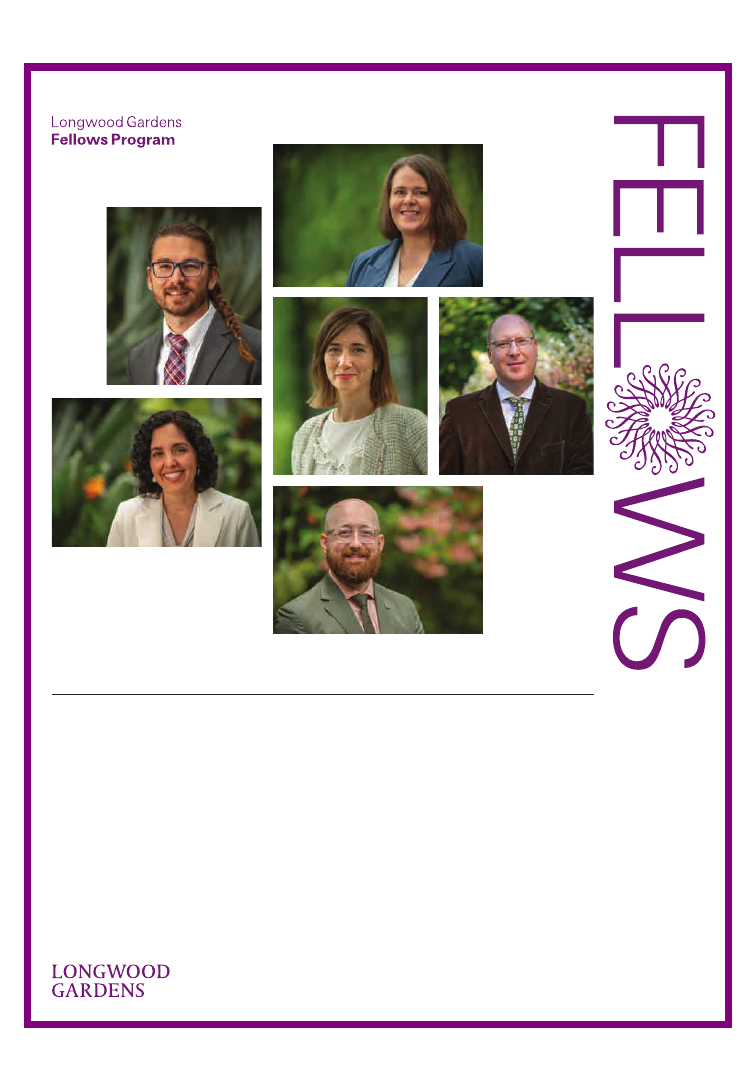

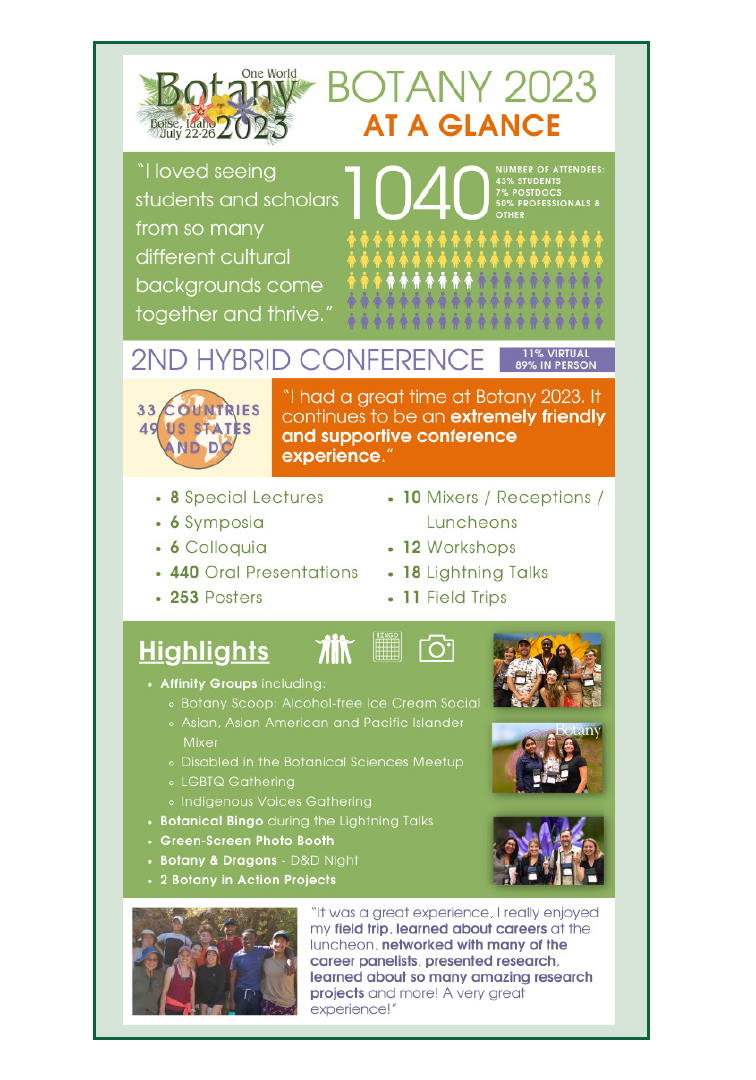

Botany 2023At A Glance......................................................................................................................................... 254

MEMBERSHIP NEWS

BSA Spotlight Series.................................................................................................................................................. 257

BSA Professional Highlight Series...................................................................................................................... 258

New AJ Harris Graduate Student Award........................................................................................................ 259

BSA Student Chapter Updates..............................................................................................................................259

It's Renewal Season .....................................................................................................................................................260

PSB

Print Subscription Change

............................................................................................................................

260

Year-End Giving.............................................................................................................................................................260

2023 BSA Gift Membership Drive .......................................................................................................................261

New BSA Ad Hoc Committee................................................................................................................................261

SCIENCE EDUCATION

Updating BSA’s State-by-State Botanical Resource Pages Please Help!.................................... 264

PlantingScience Updates......................................................................................................................................... 264

Meet Our F2 Fellows .................................................................................................................................................. 265

Read About Digging Deeper.................................................................................................................................. 266

STUDENT SECTION

Botany 2023 Review................................................................................................................................................... 268

IN MEMORIAM

Dr. Joel Fry (1957-2023)....................................................................................................................................... 270

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Dr. John Kiss Featured on The Space Show............................................................................................. 273

BOOK REVIEWS.................................................................................................................................................

274

S

tart Planning for

See logo description on inside back cover

161

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

SPECIAL SECTION

Art in the Botanical Sciences:

Past, Present, and Future

As you may have guessed from the cover, this is no ordinary issue of the PSB! You are reading the first

in a multiple-issue anthology dedicated to art and the botanical sciences. We, your guest editors, are a

group of graduate students from four universities who are passionate about the intersections of botany,

art, and personal expression. This anthology grew out of our first workshop on botanical art at Botany

2022 in Anchorage, AK. As artist-scientists, we have worked to create spaces where our colleagues can

discuss their complex, and sometimes challenging, experiences of bridging the gap between disci-

plines. The PSB editorial team invited us to expand on the ideas shared in our workshop via a special

issue. We accepted with enthusiasm and set to work soliciting abstracts for an issue that celebrated

the many ways that people integrate art and botany. We received so many exciting proposals that the

resulting pieces will be published in three(!) consecutive issues of the PSB.

In this issue, you will learn about a variety of artist-scientist collaborations, integrations of art and

science in museums, scientists’ and artists’ accounts of what drives their curiosity and exploration, and

the role of art in teaching and herbarium curation.

In preparing this issue, we learned that “anthology” comes from the Greek anthologéō, or “I gather

flowers.” How fitting for a collection of works that celebrate the beauty and wonder of the botanical

world. We hope the pieces featured in this anthology inspire you to envision how creativity can enrich

our lives as scientists, artists, and educators.

Enjoy!

The SciArt Collective

Nicolette Sipperly, Stony Brook University

Rosemary Glos, University of Michigan

Kasey Pham, University of Florida Patricia Chan, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Ashley Hamersma, University of Florida

162

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

ABSTRACT

To reach broader audiences, science

communication must move towards imaginative

and unconventional methods of conveying

research and knowledge. I use embroidery to

weave together my personal, scientific, and cultural

experiences and share them with not only other

scientists but general audiences and my family.

I grew up helping my grandparents forage for

medicinal plants, weed their crop fields, and herd

our family cattle every summer in the grasslands

of Mexico. Our daily work required knowledge

of when and where plants grow, when to harvest,

and when to rotate cattle. Despite my exposure to

botany and ecology at an early age, I never linked

my family’s cultural knowledge to these fields of

science. The more I researched about my Mexican

heritage, the more proof I found of various ways

to transfer knowledge via cultural practices.

Traditional embroidery has long been a way

for people to record the plants and animals that

Weaving Together Culture and Ecology to

Express My Identity as a Scientist

were present on the land, as well as an important

way to share important stories and lessons. As a

scientist, I integrate my culture into my work by

using embroidery to communicate my research,

study species, and express my identity through

art. This form of transferring knowledge also

helps promote cultural diversity and inclusivity

in science. Given that information is conveyed

mainly through visualizations rather than text

via embroidery and other art forms, SciArt also

removes language barriers that may prevent

individuals from engaging with science. Although

I use embroidery here as an example of expressing

my identity as a scientist, I encourage others to

find ways to express their science using other

forms of media (e.g., sculpture, dance, song) that

provide creative avenues for passing knowledge

from one generation to the next.

I was fortunate to spend my childhood summers

in the semi-arid grasslands of Zacatecas, Mexico

with my grandparents. Surrounded by a diverse

range of flora and stunning exposed cliffs, I

was captivated. My grandparents taught me the

importance of being land stewards, showing me

how to rotate cattle to ensure plant regrowth

the following year and how to identify and use

plants with ethnobotanical properties. These

were all lessons that had been passed down

orally for generations in my family. Although

I was not consciously aware of it at the time,

these experiences were integral to developing

my scientific worldview, but I would not begin to

link my family’s cultural knowledge to scientific

concepts in ecology until college. This realization

Clarissa Rodriguez

Plant Biology Ph.D. Candidate,

University of California-Riverside

163

allowed me to self-reflect on my identity and

explore other forms of transferring knowledge in

Mexican culture that I may have overlooked. I was

captivated by the use of artisan’s hand embroidery

to convey stories and even record flora and

fauna that were present on landscapes through

beautiful images created on textiles using colorful

threads. Today, I am continuing this tradition by

using embroidery to communicate my science

with broader audiences, express my identity as a

Mexican-American scientist, and weave together

my scientific training and heritage in hopes

of encouraging the representation of cultural

diversity and knowledge in science.

As a first-generation Mexican-American, I wanted

to fit in with my peers, and sometimes fitting in

came at the cost of suppressing my own Mexican

heritage. My mother started to teach me how to

embroider when I was 10, showing me the various

stitching techniques my great-grandmother had

taught her. As a child, I was eager to learn how

to use stitches to display intricate flowers, birds,

and mammals. But as I entered my teenage years,

I spent less time practicing my embroidery until I

stopped altogether to make time for other hobbies

that I could share with my American friends. I had

also stopped making my annual trips to Mexico

due to heavy cartel violence that was rampant at

the time. This change meant that I could no longer

engage in ranching, farming, or family gatherings

in Mexico—activities that had always been a

central part of my life. Consequently, this led to

an identity crisis where I found myself identifying

more with my American companions and losing

the firm grip I had on my Mexican roots.

During my college years, I wasn’t entirely sure

about my cultural identity, but I knew for certain

that I wanted to become a scientist to solve the

environmental concerns plaguing our world.

My understanding of science was limited to the

Western perspective, where trained scientists

collected data and validated it through peer review.

However, it wasn’t until I took an undergraduate

ecology course that I realized how much my

grandparents’ traditional practices were rooted in

the fields of community and restoration ecology. It

was foolish of me to not recognize earlier that their

knowledge of rangelands and natural resource

management was science. Their ecological

knowledge was accumulated over generations of

trial and error, and this realization encouraged

me to reflect on my identities. In turn, I found

a creative outlet through SciArt embroidery to

express my cultural ties and share science.

My first attempt at merging science and art via

embroidery was unsuccessful. I had forgotten

how technical the work of embroidery was, and

my work was riddled with crooked stitches and

tension issues throughout. Although it wasn’t

pretty, I wanted to show my grandma that I had

finally found a way to share my love for science

while paying homage to my Mexican roots. After

ten years of not seeing my family in Mexico, I

made the journey to reconnect, share my work,

and seek advice on how to fix my technique. My

grandma and my aunts gave me pointers on how

to improve my technique, but also expressed joy

that “the young generation is keeping our tradition

alive.” My mother was especially proud of me for

embracing my Mexican heritage within academic

spaces, because she had witnessed my struggles

with identity for years. This trip inspired me

to design a series of hoops to convey important

concepts and processes within the field of plant

ecology.

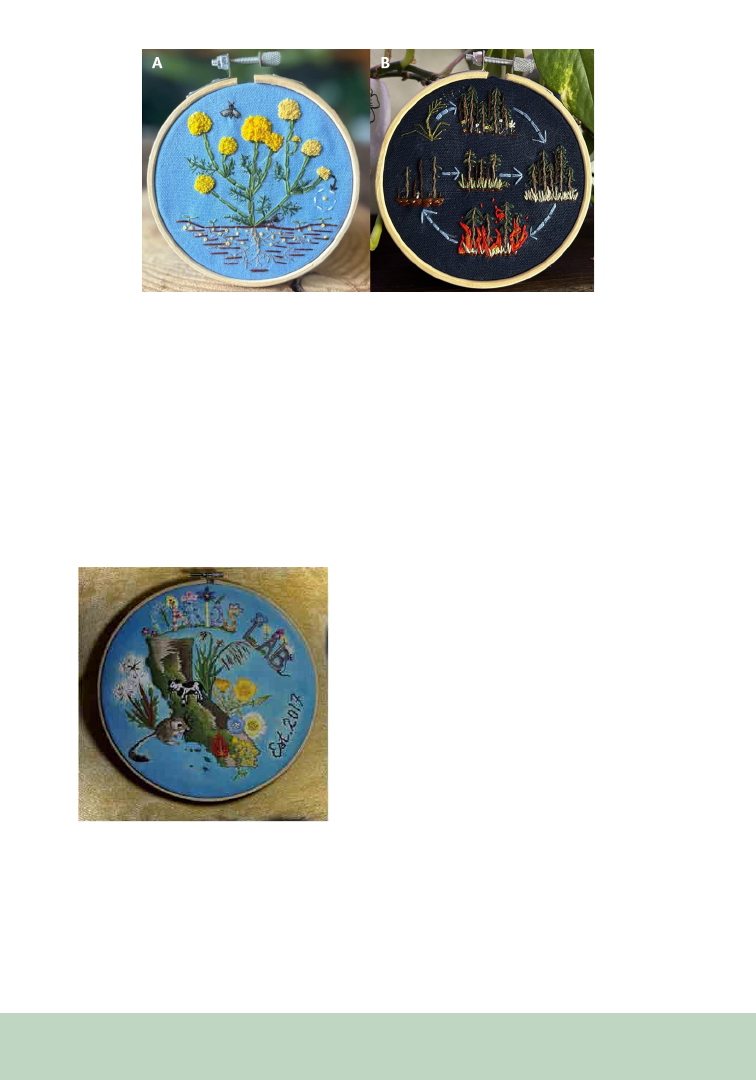

Given my scientific interests, plant invasions are

a common theme in my SciArt. For instance,

stinknet, a focal species of my dissertation, is an

invasive plant that is difficult to manage due to its

prolific seed production and persistent soil seed

bank (Figure 1A). Likewise, I created a hoop that

shows how the dispersal of introduced grasses

into a community can establish an invasive grass-

fire feedback loop by increasing biomass and fuel

continuity while suppressing native plant recovery

(Figure 1B).

A large reason why I feel comfortable expressing

myself within academic spaces is due to my

advisor’s support, Dr. Larios, who is a fellow first-

164

Figure 1. Embroidery hoops showing (A) stinknet (Oncosiphon pilulifer) accumulating seeds in the seed bank, and

included a harvester ant (Pogonomyrmex rugosus) crawling along the soil surface to depict a collaborative study in-

vestigating the role of harvester ants in dispersing invasive plants, and (B) invasive grass-fire cycle that establishes once

invasive grasses disperse into a community, which creates a litter layer that adds fuel and connectivity that carries fire

easily and creates a feedback loop to maintain invader dominance while suppressing native recovery.

generation Mexican-American, and an incredible

scientist. To show my appreciation for her

dedication to creating an inclusive workspace, I

designed and embroidered a hoop to represent the

various research topics (e.g., trophic interactions,

coexistence and land management) she studies

Figure 2. A 12-inch embroidery hoop I made for my

PhD advisor, Dr. Larios, to showcase the wide scope of

her community and restoration ecology research pro-

gram in California, which was established in 2017.

throughout California (Figure 2). One of my

favorite things about embroidery is the removal

of a language barrier. One can stare at a hoop

and recognize the heterogenous landscape of

California, along with the biodiversity of plant

species, herbivores (e.g., cows, kangaroo rats)

and fire on the landscape hinting at ecological

processes.

SciArt is a powerful tool for self-expression

and knowledge transfer that can reach broader

audiences and increase inclusivity in science. For

many individuals who come from historically

underrepresented groups within the fields of

STEM, this is a way for us to help integrate forms

of cultural knowledge and dissemination into

a Western-dominated society. Peer-reviewed

journals are already recognizing the power of

art to convey information by requiring graphical

abstracts (i.e., visual representations of the article’s

main findings). Although I use embroidery here, I

encourage others to find their own artistic outlet

to promote their science and help them share

their story. I urge my colleagues to try out visual

and performing arts to discover their preferred

creative outlet. Above all, do not hesitate to

take the first steps toward integrating art with

botanical sciences, whether that means making

the initial brush stroke, threading the first needle,

or collaborating with an artist.

165

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

In the 1980s, only one species of the genus Anisotes

was known in Madagascar. However, a specimen

on loan to the California Academy of Sciences

(CAS) from the National Museum of Natural

History in Paris seemed to be from the same genus

but with distinctive leaf and flower shape. Daniel

Thomas of the CAS wanted to know more, so he

asked botanical illustrator Erin Hunt to draw the

plant from the specimen. The result was different

from what he expected, but Hunt thought she

had captured the form correctly. When CAS

botanists went to Madagascar with the drawing

in hand, they found the plant, identifiable from

the drawing. Hunt had been right (Daniel et al.,

2007).

Such stories are rather common in botany.

After the illustrator Patricia Fawcett at Fairchild

Botanical Garden drew a flower from life with

Maura Flannery

Doctor of Philosophy, St. John’s University,

Department of Computer Science,

Mathematics and Science, New York, NY

Art in the Herbarium?

too many floral parts to fit the taxon description,

botanists realized intra-species variation required

amending the description (Stevenson and

Stevenson 2014). Conceptualizing a given species

can involve several different kinds of input ideally

including fresh and preserved material, but also

hand-drawn illustrations. The emergence of

modern botany in the 16th century was based on

this assumption, which required the rejection of

classical authorities’ deep distrust of hand-drawn

illustrations (Reeds, 1976). It is not surprising

that Luca Ghini (d. 1556), the director of the first

botanic garden in Pisa, was a very early proponent

of herbaria and field trips as well as a collector of

drawings and printed artwork, some from the first

printed herbals with good illustrations (Findlen,

2017). It quickly became common for botanists

to trade or borrow both specimens and images,

as they moved away from reliance on classical

authorities who distrusted plant drawings.

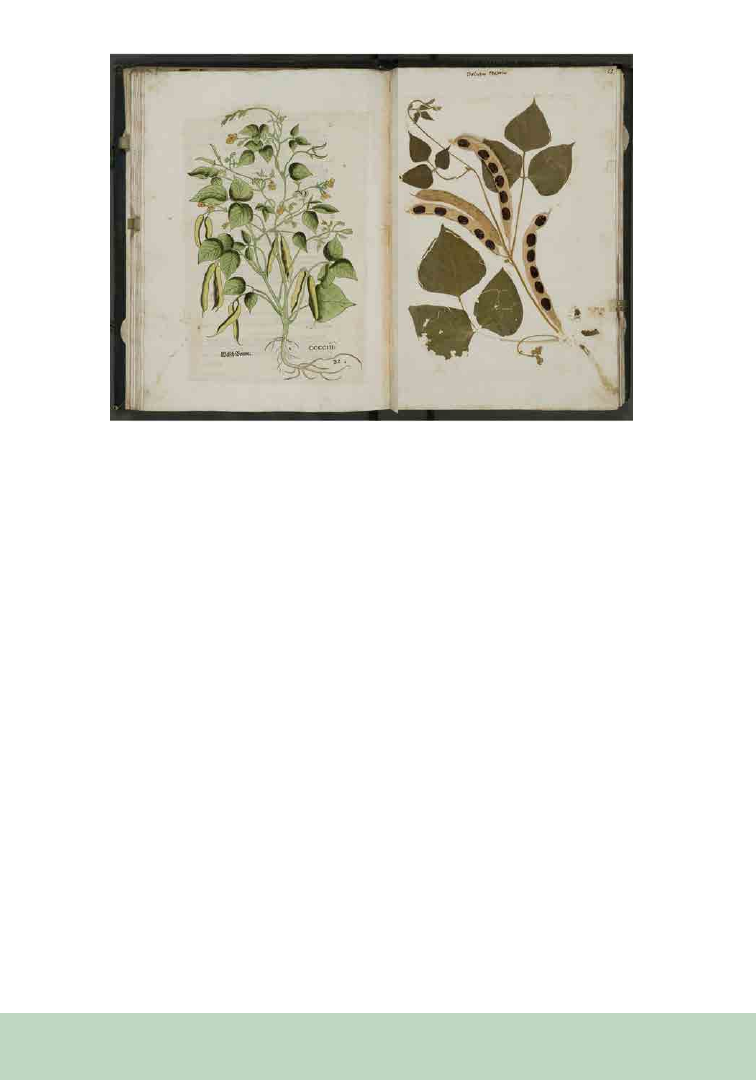

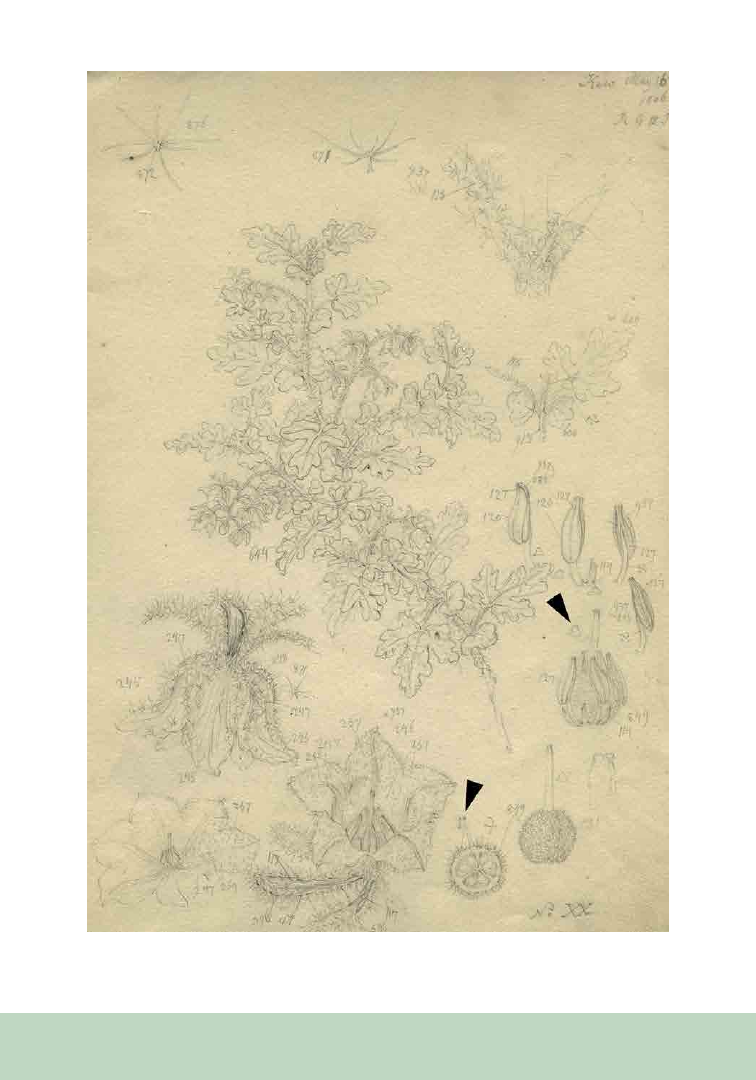

The Swiss naturalist Felix Platter (1536-1614)

arranged his bound collection so that in many

cases he would have one or more images on the

left-hand page, and a specimen of the same species

on the right (Figure 1; Benkert, 2016). On the

other hand, the Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi

(1522-1605) stored his specimens and watercolors

separately. Some early modern botanists used

other visual technologies including nature prints

and rubbings to get information about plants into

a portable reference format. There were even

some who painted in missing parts of a specimen.

Because botanical terminology was in its infancy,

visual representations could differentiate among

similar species in ways that written descriptions

166

could not. Those interested in plants preferred

to receive drawings rather than text. Some argue

that it was the illustrations that pushed botanists

to write descriptions of equal clarity, and that

the artists of the age were influential in causing

botanists to observe more closely (Smith, 2003).

The relationship between drawing and knowing

has become a topic of interest among historians

of art and science. The astronomer Omar Nasim

(2013) describes how repeated drawing of nebulae

in the 19th century clarified the concept of an

astronomical phenomenon that, as its name

suggests, was blurry. As more observations were

made, as drawings were repeated night after night,

these hazy structures become more familiar to the

observer’s eye, mind, and hand. Drawings were

tools in the process of discovery and knowledge

stabilization. In drawing, the hand slows down

observation, allowing the mind to synthesize.

Barbara Wittmann (2013) reports on a scientific

illustrator’s experiences working on a new fish

species where getting the drawings correct led him

to discover novel anatomical features. Botanists

who choose to do at least their own preliminary

drawings have similar experiences. As they draw

plant structures repeatedly, often from different

perspectives or from different dissections, they

find themselves learning more and having to

correct their drawings and written descriptions

along the way.

If a professional illustrator is doing artwork, there

is a back-and-forth, with the botanist making

corrections. This is what Lorraine Daston and Peter

Galison (2007) term “four-eyed sight,” producing

a more informative image than one pair of eyes

could. Clarity and discovery arise from this give-

and-take. A drawing helps both the botanist and

the audience to understand more about the plant.

The zoologist and illustrator Jonathan Kingdon

(2011) appeals to research on the neurophysiology

of sight to explain why pen and ink drawings and

prints are particularly useful. The human brain

processes signals from the eyes by detecting edges

and accentuating them. This means that black-

and-white illustrations communicate information

especially effectively because they are in tune with

the brain’s visual processing system.

Figure 1. From Felix Platter’s herbarium (volume 7, pp. 86-87). Hand-col-

ored woodcut image of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) from the Ger-

man edition of Leonhard Fuchs’s 1542 herbal, facing specimen of the same

species. Courtesy of Bern City Library.

167

As more and more new plants were discovered

around the world beginning in the 1500s, botanists

were challenged with naming and describing

them. There was a fervor among many to publish

new species as soon as possible, often based only

on specimens or drawings sent to them. Even

Carl Linnaeus described many species solely on

the basis of watercolors or printed black-and-

white illustrations. When his species descriptions

were later typified, these images became

lectotypes since they were the only materials he

had examined. This was true for other botanists

as well, although now the practice is only allowed

in defined cases in the International Code of

Botanical Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants

(Turland and Wiersema, 2018).

Pragmatically, drawings of plants also serve as a

back-up to specimens and descriptions. The plants

of New Spain that were collected in the late 18th

century by the Sessé and Mociño Expedition

reached Spain safely, but their analysis and

publication was disrupted by Martin de Sessé’s

death and the Napoleonic Wars. José Mociño

fled to France, taking with him some written

descriptions and nearly 2000 illustrations made

during the expedition. In Montpellier, he shared

this hoard of information on undescribed species

with Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, who was

writing a comprehensive work on the world’s

plants. De Candolle regarded these watercolors

and sketches as so valuable that he had them hastily

copied by a large team of artists before Mociño

returned to Barcelona. After Mociño’s death there,

the originals were lost until 1979! Consequently,

for more than 150 years, de Candolle’s annotated

copies became the primary source of information

about hundreds of New World species (McVaugh,

1998).

In the 18

th

and 19

th

centuries, British colonial

administrators in India created botanical gardens

as a way to gather and observe many species to find

those that could be sources of food, medicines,

and useful items such as textiles and timber

wood. Meanwhile, botanists collected thousands

of specimens in support of this effort. It became

standard practice to have Indian artists paint

watercolors of many of these plants. This was not

just to have a record of a plant’s color and form,

but also to ensure that there was any record at all.

In tropical climates, conditions sometimes drove

collectors to rely on nature prints and drawings. It

was difficult to preserve specimens in hot humid

areas and to prevent insect and fungal damage.

In the 20

th

century there were botanists like Oakes

Ames at Harvard who included ink drawings and

watercolor sketches by his artist wife Blanche Ames

on his orchid specimens. This approach continues

as drawings of flower dissections and microscope

enlargements of structures are added to sheets by

botanists and artists. Because of the importance

of having different kinds of information about a

plant available at the same time, such practices

persist, but there has been a change in storage

practices. In the past, illustrations of a species

were often stored in the same folder as specimens

of that species. This was handy for botanists but

perhaps not so good for the art, which could be

damaged by substances leaching from the plants.

With the start of digitization projects, when

folders that hadn’t received attention for years

were examined, it became common to remove the

illustrations, particularly if they weren’t physically

attached to the specimens. They are now usually

stored separately, often in the library or archives

affiliated with the herbarium.

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RGBE)

has a large number of Indian plant specimens,

many collected by physicians who had trained

in Edinburgh and later served Britain’s massive

colonial enterprise in India. Henry Noltie, then

a curator at the RBGE herbarium, spent months

going through folders, removing the images created

by Indian artists and successfully re-sorting them

from taxonomic order into separate collections,

many donated by one person or organization

and in some cases created by a single Indian

168

artist or by a small group. Noltie was often able

to identify the artists by name, but others remain

anonymous. Through this work, Noltie learned

a great deal about the collections and the people

related to them, producing several books on these

works (Noltie, 2002, 2017). The art is now stored

in the RBGE archives, along with correspondence

and other papers from those responsible for the

specimen and art collections. The Royal Botanic

Gardens Kew and many other institutions have

done the same.

This policy makes the illustrations more available

to those interested in the historical and artistic

significance of these works and keeps them

together as collections so they can be compared

in terms of style. In other words, the images are

now treated more as works of art than of science,

perhaps to the detriment of science. What might

be good for the botanical art and for the history

of art and botany, might not be the best solution

for botanical inquiry. Past collectors of Indian

botanical art were often as interested in them as

works of art as of science, and today this is true

for many who collect botanical art. However, both

the art and specimens were created as scientific

documents, whether or not they had any obvious

aesthetic appeal. The botanist Peter Crane (2013)

considers botanical illustration as important

today as it was hundreds of years ago, but notes

economics has changed the picture. Today, color

images are rare in taxonomic treatments of new

species, and even pen-and-ink illustrations are

less prevalent, even though, for all the reasons

discussed earlier, illustrations can provide vital

information to botanists.

The works described here were created as adjuncts

to specimens, living and preserved, and they should

be able to continue to function this way. Opening

up a species folder and finding illustrations can

provide a botanist with information on color and

form less likely to be documented in the specimen

itself, thus making it easier to create a full mental

image of the plant. If the illustrations are stored

elsewhere, this richness is lacking. A trip to the

archives would be necessary to see the relevant

drawings. Since some of the art collections have

been digitized, and herbaria are continuing to

digitize their collections, it should be possible to

link a specimen to one or more illustrations of that

specimen as one facet of the extended specimen

concept.

Implementing such an idea is hardly trivial.

The databases used in science and those for art

and archival materials are often quite different.

There are moves toward standardization across

platforms, but implementation will not be easy.

The work of developing what is called FAIR

data—Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and

Reusable—is substantial (Manzano and Julier,

2021). The colonial origin of a good deal of both

types of collections needs to be acknowledged as

well. However, my focus here is on the value of

linking art to science, an important component

since the 16th century. It is as important today

not only for what botanists can learn about

plants but for the aesthetic lift that comes with

examining these works, even if the goal is to seek

out taxonomic information. The botanist Richard

Mabey’s (2015) comment is relevant here: “The

quintessence of a plant can only ever be a fantastic

goal, something to travel towards but never reach”

(p. 27). That’s why we need to dig into—and

preserve—different types of information: living

plants, specimens, art, and photography, which

should not be forgotten but is outside the scope

of this article.

REFERENCES

Benkert, D. 2016. The ‘Hortus Siccus’ as a focal point:

Knowledge, environment, and image in Felix Platter’s and

Caspar Bauhin’s herbaria. In S. Burghartz, L. Burkart, and

C. Göttler (Eds.), Sites of Mediation, 211–239. Brill, Leiden.

Crane, P. 2013. Gingko: The Tree that Time Forgot. New Ha-

ven, CT: Yale University Press.

Daniel, T. F., B. A. V. Mbola, F. Almeda, and P. B. Phillipson.

2007. Anisotes (Acanthaceae) in Madagascar. Proceedings of

the California Academy of Sciences 58: 121–131.

169

Daston, L., and P. Galison. 2007. Objectivity. Zone, New

York.

Findlen, P. 2017. The death of a naturalist: Knowledge and

Community in Late Renaissance Italy. In G. Manning, C.

Klestinec (Eds.), Professors, Physicians and Practices in the

History of Medicine, 127–167. Springer, New York.

Kingdon, J. 2011. In the eye of the beholder. In M. R. Can-

field (Ed.), Field Notes on Science and Nature, 129–160. Har-

vard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Mabey, R. 2015. The Cabaret of Plants: Forty Thousand Years

of Plant Life and the Human Imagination. Norton, New York.

Manzano, S., and A. C. M. Julier. 2021. How FAIR are plant

sciences in the twenty-first century? The pressing need for

reproducibility in plant ecology and evolution. Proceedings of

the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288: 20202597.

McVaugh, R. 1998. Historical introduction. Torner Collection

of Sessé and Mociño Biological Illustrations, Hunt Institute for

Botanical Documentation. Website: https://www.huntbotani-

cal.org/art/show.php?10.

Nasim, O. W. 2013. Observing by Hand: Sketching the Nebu-

lae in the Nineteenth Century. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

Noltie, H. J. 2002. The Dapuri Drawings: Alexander Gibson

and the Bombay Botanic Gardens. Antique Collectors’ Club,

Edinburgh.

Noltie, H. J. 2017. Botanical Art from India: The Royal Bo-

tanic Garden Edinburgh Collection. Royal Botanic Garden

Edinburgh, Edinburgh.

Reeds, K. M. 1976. Renaissance humanism and botany. An-

nals of Science 33: 519-542.

Smith, P. H. 2003. The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experi-

ence in the Scientific Revolution. University of Chicago Press,

Chicago.

Stevenson, J. W., and D. Wm. Stevenson. 2014. The nuts and

bolts of doing the Flora of the Bahama Archipelago: How Don

Correll worked. The Botanical Review 80: 135–147.

Turland, N. J., and J. H. Wiersema (Eds.). 2018. International

Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants. Koeltz,

Oberreifenberg.

Wittmann, B. 2013. Outlining species: Drawing as a research

technique in contemporary biology. Science in Context 26:

363–391.

170

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

The Significance of Illustrations as Nomenclatural Types in

Botany: “Iconotypes” at the Natural History Museum

Vienna, and the Importance of Color Systems,

Such as Those Utilized by Ferdinand Bauer [1760–1826]

Tanja M. Schuster

1,7

Mario-Dominik Riedl

2

Sarah Fiedler

3

Martin Krenn

2

Heimo Rainer

1

David J. Mabberley

4,5,6

1

Natural History Museum Vienna, Department of Botany,

Herbarium, Burgring 7, 1010 Vienna, Austria

2

Natural History Museum Vienna, Department Archive for

the History of Science, Burgring 7, 1010 Vienna, Austria

3

Natural History Museum Vienna, Libraries Department,

Burgring 7, 1010 Vienna, Austria

4

Wadham College, University of Oxford, Parks Road,

Oxford OX1 3PN, United Kingdom

5

School of Natural Sciences, Macquarie University, Mac-

quarie Park, New South Wales 2109, Australia

6

Australian Institute of Botanical Science (Royal Botanic

Gardens and Domain Trust), Mrs Macquaries Road, New

South Wales 2000, Australia

7

Author for correspondence: tanja.schuster@nhm-wien.ac.at

ABSTRACT

Aside from the more commonly selected

herbarium specimens for this purpose, a botanical

illustration—in particular, a historical one—

can also serve as type for the name of a taxon.

The Archive for the History of Science at the

Natural History Museum Vienna holds many

such “iconotypes.” These include illustrations

used in Jacquin’s, Schott’s, and others’ taxon

descriptions. Additional drawings of great value

for taxonomy are annotated field sketches, such

as those by Ferdinand Lukas Bauer. The field

drawings, often with locality data and dates of

observation, enabled him to produce colored

plates of exceptional aesthetic and scientific

quality by employing numerical and other codes

to document color, hue, brightness, opacity, and

texture of morphological features.

KEYWORDS

Australia, Linnaeus, natural history collections,

New Holland, Norfolk Island, nomenclature,

typification

HISTORICAL ILLUSTRATIONS AS

NOMENCLATURAL

TYPES FOR PLANT NAMES

Although the term “iconotype” is not formally

used in the International Code of Nomenclature

for Algae, Fungi, and Plants (ICN), it is generally

understood to be an illustration that serves as

the type for the name of a taxon. For example,

the lectotypes of many Linnaean binomials in

botany and zoology are illustrations (Jarvis, 2007,

2008). When a type specimen is lost or destroyed,

illustrations prepared from the original material

can be candidates for types; such illustrations are

obligate lectotypes when all other original material

has been lost.

171

“Iconotypes” at the Natural History

Museum Vienna Archive

The Archive for the History of Science at the

Natural History Museum Vienna (NHMW) houses

a significant collection of historical illustrations,

some of which are types for names of animals,

fungi, and plants (for example, illustrations by

Nikolaus von Jacquin [1727–1817], Joseph Franz

von Jacquin [1766–1839], and Heinrich Schott

[1794–1865]).

Most of Schott’s specimens of Araceae were

destroyed in a fire at the end of WWII (see Riedl,

1981) so that taxonomists (e.g., Coelho, 2000) have

to rely on Schott’s illustrations of original material

for typification (Figure 1). Other examples are

mycological illustrations in Jacquin (1776), as

few, if any, of Jacquin’s specimens of fungi have

survived; for example, the published illustration

of Boletus cinnabarinus Jacq. (= Pycnoporus

cinnabarinus (Jacq.) P.Karst., Polyporaceae) is the

type (see link in References).

One Step Beyond: The Field

Drawings of Ferdinand Lucas Bauer

Use of illustrations as types is facilitated if they

were made using standardized coloration. An

outstanding example of this is the work of

Ferdinand Lucas Bauer (FLB), whose pencil field-

sketches, now almost all at NHMW, were the bases

for colored illustrations (mostly now at BM), some

of which are types. The drawings are important,

because they include information omitted from

the final, colored illustrations, such as collection

localities, dates, and additional detailed sketches of

descriptive morphological characters (Mabberley,

2021). The sketches also bear FLB’s notations using

numerical and other codes, which indicate the hue,

brightness, opacity, and texture of particular parts

of the living organism (Figure 2). FLB did this to

document rapidly the coloration of a specimen in

the field with a view to his “reviving” this later in

watercolor.

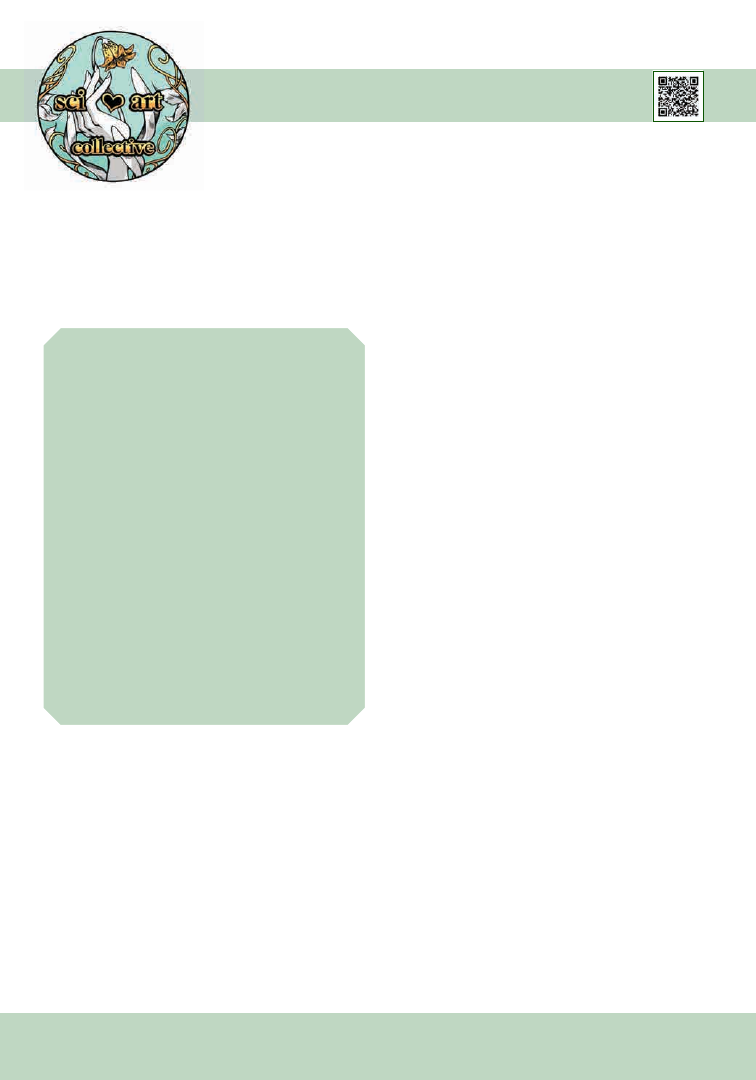

Figure 1. Note that this figure can only be accessed elec-

tronically via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7874857.

The lectotype for Philodendron imperiale Schott, a

synonym of Philodendron ornatum Schott (Araceae),

‘Schott Aroideae’ No. 3620 (see arrowhead). Most of

Schott’s specimens were destroyed in a fire at the end of

WWII, and taxonomists use the illustrations of original

material commissioned by Schott (this one done by W.

Liepoldt, double arrowhead) for typification.

FLB’s drawings recorded for the first time many

Australian species then new to Western science, as

he accompanied Matthew Flinders’ voyage (1801–

1803), the first documented circumnavigation

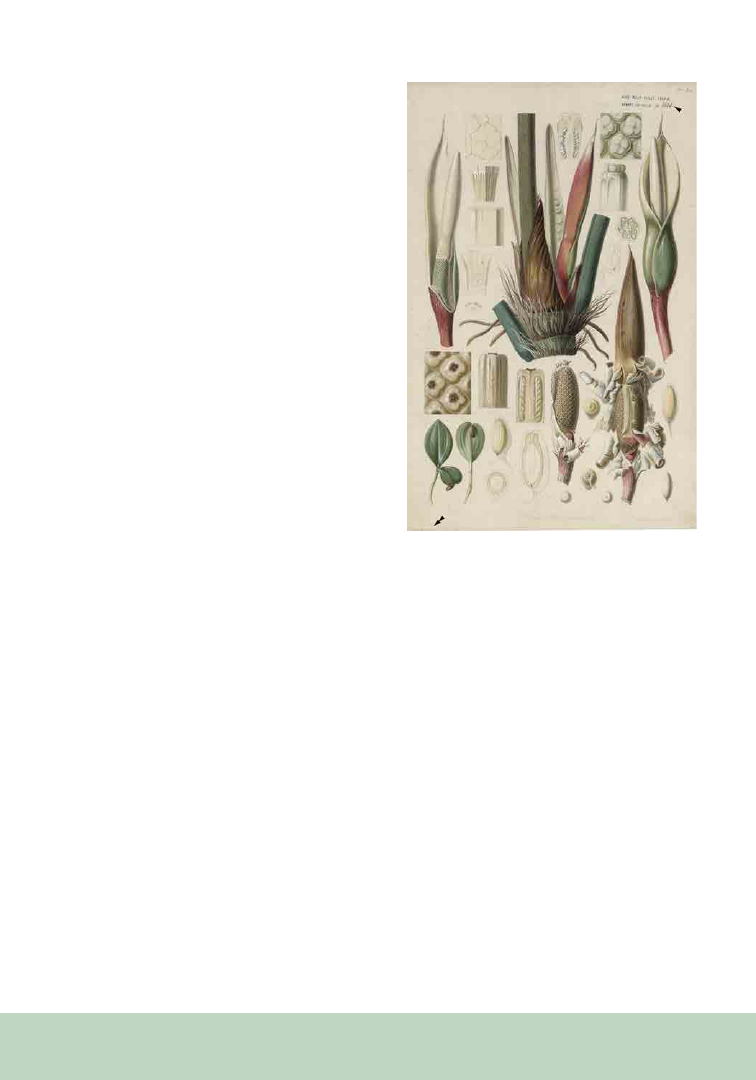

of the continent. For example, Figure 2 shows

an as-yet-undescribed species of Thomasia, a

genus restricted to Australia (Malvaceae). This is

likely T. sp. Vasse (Wilkins and Shepherd, 2019;

but see Shepherd and Wilkins, in preparation).

Exceptionally, the notation on the drawing

indicates that FLB drew it at Kew Gardens,

where the plant was raised from seed, most likely

collected during the expedition.

172

Figure 2. Drawing by Ferdinand Lucas Bauer of an undescribed species of Thomasia currently listed as T. sp. Vasse

(Malvaceae). Note that the numbers on the drawing correspond to numerical codes Bauer used to indicate hue, bright-

ness, opacity, and texture of a particular structure. The arrows point to additional symbols, such as sigils.

173

Color Charts for Standardization

in Historical Illustration as

Used by Bauer

FLB used the “painting by numbers” technique

throughout his career (Mabberley, 2017). His

color-code evolved over time and could have

been derived from principles in, or partial use

of, color systems developed by others. These

include Brenner (1680); Estner (1794), which is

specifically referenced on some of FLB’s Pacific

drawings (Mabberley, 2017, 2019); Schäffer (1769);

Schiffermüller and Denis (1771); Struve (1797);

Werner (1774); Widenmann (1794); Willdenow

(1799); and, perhaps, that associated with Haenke

(see Lack and Ibáñez Montoya, 2004, but also

Mabberley and San Pío Aldarén, 2012). FLB may

also have utilized color tables used by various

tradespeople (ceramics painters, printers, tanners)

and chemists (Pörner, 1773; Gülich 1779, 1780,

1781, 1786). Over time, he used an increasing

range of numbers, and the later work, in Australia,

included values close to 1000 (Pignatti-Wikus et

al., 2000) for botanical subjects, and beyond in the

later zoological drawings made on Norfolk Island.

However, FLB’s elaborate color chart is lost (Riedl-

Dorn and Riedl, 2019), if it ever existed (Mabberley

and San Pío Aldarén 2012; Mabberley, 2017, 2019,

2022; Jelley, 2022). Jelley (2022) has a practical

explanation for the numerical code based on an

art practitioner’s process, showing that the layout

of FLB’s paintbox may have functioned as his aide-

memoire and that the numbers could have been a

two-part code. The first one or two digits specified

which pigment to use, and the last digit(s) were

directions on how to achieve the correct blend,

brightness, opacity, etc. In other words, if this

hypothesis is proved, there probably never was a

physical color-chart of FLB's.

In addition to numbers, FLB used many additional

ciphers, especially in his later zoological drawings.

These include planetary symbols to convey

information about color, in that they were then

commonly understood to correspond to metals

such as gold for the sun ( ), silver for the moon

( ), and so on. However, FLB sometimes also wrote

the actual words “gold” or “silver” on drawings

together with the symbols. We assume therefore,

that the symbols had additional meaning and

may also refer to particular color blends, pattern,

texture, brightness, and/or opacity for that color

(e.g., yellow for ). Bauer also used upper- and

lower-case letters, maybe corresponding to those

in the tables of Schiffermüller and Denis (1771),

but also see Pignatti-Wikus et al. (2000), sigils

(symbols used in alchemy and magic; see Figure

2), and the Greek alphabet. Roman numerals

usually indicate the number of any particular

structure (e.g., stamens in a flower, spines of a fish

fin). It is currently mostly unclear, though, what

these additional symbols exactly mean. Jelley

(pers. comm.) is conducting further research into

these more complex layers of information in FLB’s

Australian work.

The importance of Ferdinand Bauer’s drawings at

the NHMW to taxonomic biology, as “iconotypes”

and otherwise, is only now beginning to become

clear. A thorough investigation of the collections,

necessarily involving international collaboration,

is much needed (Mabberley, 2021). In addition

to their immeasurable scientific and aesthetic

value, these drawings document the Australian

flora largely before European settlement. It would

therefore be important to make them available

to a broader audience. This will require funding

for a collaboration between Australian botanists,

NHMW staff (archive, botany, and library), and to

hire project-based digitization staff.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the reviewers for helping to improve

the manuscript, as well as Trevor L. Blake, Kelly

Shepherd (PERTH), and Carol Wilkins (PERTH)

for refining our Thomasia identification.

174

DATA AVAILABILITY

STATEMENT

High-resolution scans of the illustrations shown

and other “iconotypes” are available upon request

for research purposes via the Archive for the

History of Science at the Natural History Museum

Vienna (archiv@nhm-wien.ac.at).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of

interest.

FUNDING

This project was not supported by external

funding.

AUTHORSHIP

S.F.: review and editing (equal); M.K.: review and

editing (equal); D.J.M.: conceptualization (equal),

writing – review and editing (supporting);

H.R.: review and editing (equal); M.-D.R.:

conceptualization (equal), writing – review and

editing (supporting), figure preparation (lead);

T.M.S.: conceptualization (equal), writing –

original draft (lead), writing – review and editing

(lead), figure preparation (supporting).

REFERENCES

Brenner, E. 1680. Nomenclatura et species colorum miniatae

picturae. Stockholm, Sweden. Website: https://weburn.kb.se/

metadata/146/EOD_2514146.htm

Coelho, M. A. N. 2000. Philodendron Schott (Araceae): mor-

fologia e taxonomia das espécies da Reserva Ecológica de

Macaé de Cima - Nova Friburgo, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Ro-

driguésia 51: 21–68.

Estner,

F. J. A. 1794. Versuch einer Mineralogie für

Anfänger und Liebhaber nach des Herrn Bergcommissions-

raths Werner’s Methode, I. Bd. J. G. Oehler, Wien, Austria.

Website: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/

bsb10283387?page=9

Gülich, J. F. 1779. Die rechte und wahrhafte Färbekunst. C. F.

Schneider, Leipzig, Germany. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.11588/

diglit.27273#0005

Gülich, J. F. 1780. Vollständiges Färbe- und Blaichbuch

zu mehrerm Unterricht, Nutzen und Gebrauch für Fabri-

kanten und Färber. A. L. Stettin, Ulm, Germany. Website:

https://books.google.at/books?id=zBVaxkKMGPoC&pri

ntsec=frontcover&hl=de&source=gbs_ViewAPI&redir_

esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Gülich, J. F. 1781. Vollständiges Färbe- und Blaichbuch wel-

ches drey der wichtigsten Hauptstücke für Fabrikanten ent-

hält. Stettinische Buchhandlung, Germany. Website: https://

www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10304876?pa-

ge=7

Gülich, J. F. 1786. Vollständige bewährte praktische Anwei-

sung zur Färberey auf Schaafwolle, Camellhaar und Seyde.

Stettinische Buchhandlung, Ulm, Germany. Website: https://

www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10304882?pa-

ge=1

Jacquin, N. J. von. 1776. Florae Austriacae sive plantarum

selectarum in Austriae archiducatu sponte crescentium, Vol.

IV. J. M. Gerold, Wien, Austria. Website:

https://www.biodi-

versitylibrary.org/item/9678#page/7/mode/1up

Jarvis, C. 2007. The art and science of typification. In Order

out of Chaos. Linnaean plant names and their types, 13–61.

The Linnean Society in association with the Natural History

Museum London, London, United Kingdom.

Jarvis, C. 2008. Linnaeus’ use of illustrations in his naming

of plants. In M. J. Morris and L. Berwick [eds.], The Linnae-

an legacy: three centuries after his birth. The Linnean Special

Issue 8: 75–84.

Jelley, J. 2022. A Puzzle in a Paintbox: A painter’s solution

to Ferdinand Bauer’s colour code for the Flora and Fauna

Graeca 1786–1794. Art and Perception. DOI: https://doi.

org/10.1163/22134913-bja10042

Lack, W. and M. A. Ibáñez Montoya. 2004. Recording co-

lour in late eighteenth century botanical drawings: Sydney

Parkinson, Ferdinand Bauer and Thaddäus Haenke. Curtis’s

Botanical Magazine 14: 87–100.

Mabberley, D. J. 2017. Painting by numbers: the life and

work of Ferdinand Bauer. NewSouth, Sydney, Australia.

Mabberley, D. J. 2019. Botanical Revelation – European

encounters with Australian plants before Darwin The Peter

Crossing Collection. NewSouth, Sydney, Australia.

Mabberley, D. J. 2021. The “London” Australian natural his-

tory drawings of Ferdinand Bauer (1760–1826) revisited.

Flora Mediterranea 31: 67–94.

Mabberley, D. J. 2022. The Peter Crossing Collection: an il-

lustrated catalogue. Peter Crossing Collection, Sydney, Aus-

tralia.

Mabberley, D. J. and M. P. de San Pío Aldarén. 2012.

Haenke’s Malaspina colour-chart: an enigma. Real Jardín

Botaníco, CSIC, Madrid, Spain

175

Pignatti-Wikus, E., C. Riedl-Dorn, and D. J. Mabberley.

2000. Ferdinand Bauer’s field drawings of endemic Western

Australian plants made at King George Sound and Lucky

Bay, December 1801 - January 1802. I: Families Brassica-

ceae, Goodeniaceae p.p., Lentibulariaceae, Campanulaceae

p.p., Orchidaceae, Pittosporaceae p.p., Rutaceae p.p., Styli-

diaceae, Xyridaceae. Rendiconti Lincei, Scienze Fisihce e

Naturali 9: 69–109.

Pörner, C. W. 1773. Chymishce Versuche und Bemerkungen

zum Nutzen der Färberkunst. Vol. 3, M. G. Weidmanns Er-

ben und Reich, Leipzig, Germany. Website: https://books.

google.at/books?id=e-cUAAAAQAAJ&pg=PP5&hl=de&s

ource=gbs_selected_pages&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

Riedl, H. 1981. Families destroyed in World War II at the

Vienna Herbarium (W). Taxon 30: 727–728.

Riedl-Dorn, C. and M. Riedl. 2019. Ferdinand Bauer or Jo-

hann and Joseph Knapp? A rectification. The Gardens’ Bulle-

tin, Singapore 71: 123–142.

Schäffer, J. C. 1769. Entwurf einer allgemeinen Farben-

verein oder Versuch und Muster einer gemeinnützlichen

Bestimmung und Benennung der Farben. E. A. Weiß, Re-

gensburg, Germany. Website: https://nbn-resolving.org/

urn:nbn:de:bvb:355-ubr12318-3

S

chiffermüller, I., and M. Denis. 1771. Versuch eines Farben-

systems. A. Bernardi, Wien, Austria. Website: https://www.

digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb10058712?page=1

Struve, H. 1797. Méthode analytique des fossiles, fondée

sur leurs caractères extérieurs. Lacombe & Co., Lausanne,

Switzerland. Website: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/

de/view/bsb10284666?page=1

Werner, A. G. 1774. Von den äußerlichen Kennzeichen der

Fossilien. S. L. Crusius, Leipzig, Germany. DOI: https://

digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/werner1774

Widenmann, J. F. W. 1794. Handbuch des oryktognos-

tischen Theils der Mineralogie. S. L. Crusius, Leipzig,

Germany. Website: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/

view/bsb10284860?page=1

Willdenow, C. L. 1799. Grundriß der Kräuterkunde

zu Vorlesungen entworfen. Von Ghelensche Schriften,

Wien, Austria. DOI: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/

item/220233#page/5/mode/1up

Wilkins, C., and K. Shepherd. 2019. A key to the species

of Thomasia (Malvaceae: Byttnerioideae). Nuytsia 30:

195–202.

176

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

As archives of historical plant specimens,

herbaria provide snapshots of environmental

landscapes across time that are continuously

accessed, recontextualized, and reinterpreted

through modern techniques. Moreover, specimen

imaging in herbaria has been key to recent global

digitization efforts that confer multiple benefits,

including facilitating taxonomic revisions and

enabling better access to biodiversity data (Soltis,

2017). Specimens also become discoverable to

non-traditional researchers, such as artists and the

interested public.

From 2019 to 2022, the University of Texas at El

Paso (UTEP) herbarium imaged and georeferenced

all its specimens (~50,000 records) from the

southwest US and Mexico, funded by two grants

(IMLS IGSM-245733 and NSF DBI1902078).

To celebrate these projects, largely conducted

by biology undergraduates, we developed the

exhibit “Where We Will Grow: Elsie Slater, Plants,

and Art” at UTEP’s Centennial Museum and

Chihuahuan Desert Gardens (Fall 2021–Spring

2022) to showcase the history, art, and science of

the herbarium. We chose to highlight Elsie Slater

Celebrating the Launch of the UTEP Virtual Herbarium by

Highlighting Contemporary and

Historical Art and Science of the El Paso Region

Mingna V. Zhuang

1,3

Nabil Gonzalez

2

Michael L. Moody

1

1

UTEP Biodiversity Collections, Biological Sciences De-

partment, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 W Univer-

sity Ave. El Paso, TX 79968

2

Art Department, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 W

University Ave. El Paso, TX 79968

3

Author for correspondence: mzhuang@utep.edu

(1871–1952), a self-taught botanist, because her

collections represented the earliest specimens

from El Paso held by our herbarium and because

her unique dual interests in both the arts and

the sciences. Slater was a writer and artist whose

works are held at UTEP (Centennial Museum

and C. L. Sonnichsen Special Collections), which

span the scientific (exceptional botanical art) to

the impressionistic. Drawing from Elsie’s diverse

interests, the UTEP Herbarium partnered with

the Art Department’s Drawing I Class taught by

Nabil Gonzalez to use specimens from Elsie’s

collections as inspiration for student art. Because

of COVID-19 restrictions, art students visited the

new digital herbarium (Project Page: https://arctos.

database.museum/project/10003615) rather than

the physical herbarium. Collections Manager

Vicky Zhuang met with the students via Zoom

during a class period to introduce the project.

She described the herbarium, provided examples

of how researchers used herbarium specimens,

and guided the students through how to use the

database to find images of specimens. Students

were then instructed by Nabil to reinterpret Elsie’s

point of view towards the botanical world and

the romance of life. Each student researched their

chosen specimens and subsequently created a

composition representing a page out of a journal.

The students were asked to restrict their search to

the El Paso area and to focus on Elsie’s collections

when possible. However, they were intentionally

not exposed to Elsie’s artworks, so they would be

inspired to develop their ideas independently and

with few limitations. With regards to the exhibit,

students were only told that their pieces would be

paired with Elsie’s works and specimens in a botany

177

and art-focused exhibit and were encouraged to

explore a variety of mixed media and concepts.

This project granted students the experience of Elsie's

creative world that blended botany and art. For

example, Elsie’s specimen sheets often had poetic

notes. When describing a Baileya multiradiata

(UTEP 6602), she noted, “…one of the brightest

gold flowers, very very beautiful for our city.” Digital

collections allowed students to thoroughly examine

these specimens by focusing on shape, form, color,

and texture. Artists take inspiration from nature

and the world around them (Flannery, 2013).

Everything they see, touch, and feel is an important

part of how artists understand and research the

creative process. Thus, the collaboration gave

art students a new perspective on the artistry

of scientific specimens through Elsie’s unique

collection.

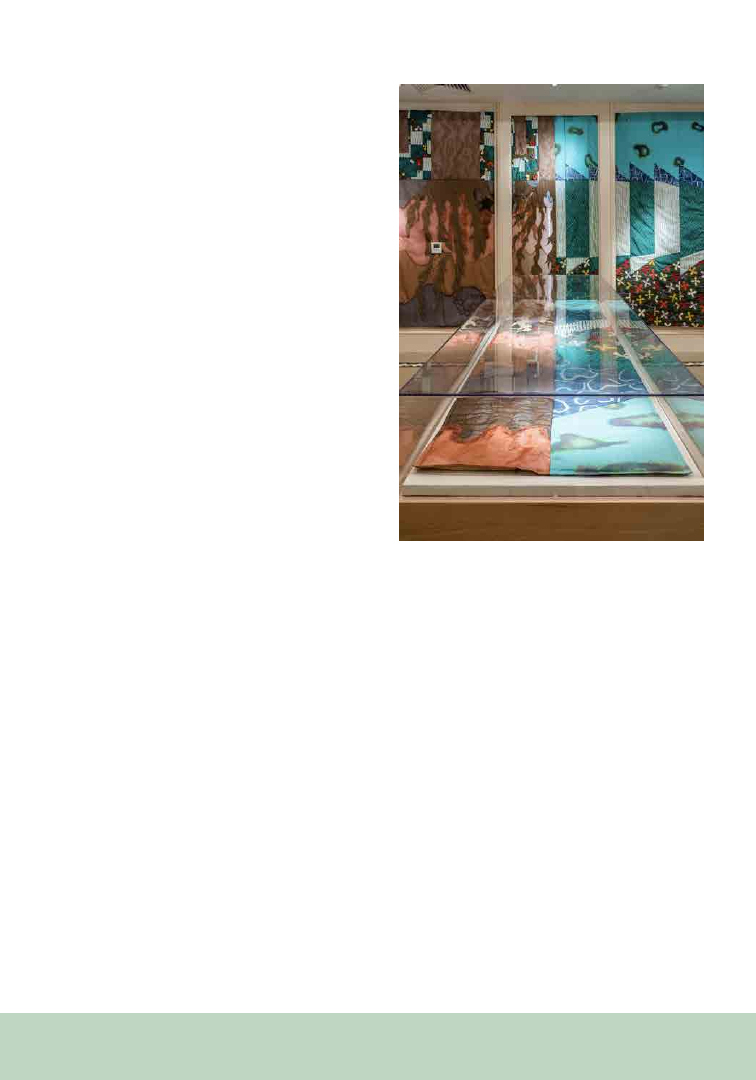

Because students were not restricted in style, the

students produced art pieces that represented

a diverse range of interpretations, realistic to

abstract, sometimes of the same specimens

(Figure 1). However, additional check-ins to

ensure the accuracy of scientific names and

species associations would have been beneficial.

Despite working independently, some students

converged on similar motifs (i.e., eyes, bones,

life, and death). Additionally, like some of Elsie’s

botanical art, some of the pieces included text (i.e.,

Figure 1B and D), as well as true-to-life reflections

of the specimens. Several art students found relief

from the pandemic lockdown and discovered new

inspiration in their local plant diversity. Finally,

biology students curating the exhibit connected to

the specimens they had been working on in a new

and broader context. Overall, the exhibit revealed

parallels in modern perspectives of science and art

using historical specimens.

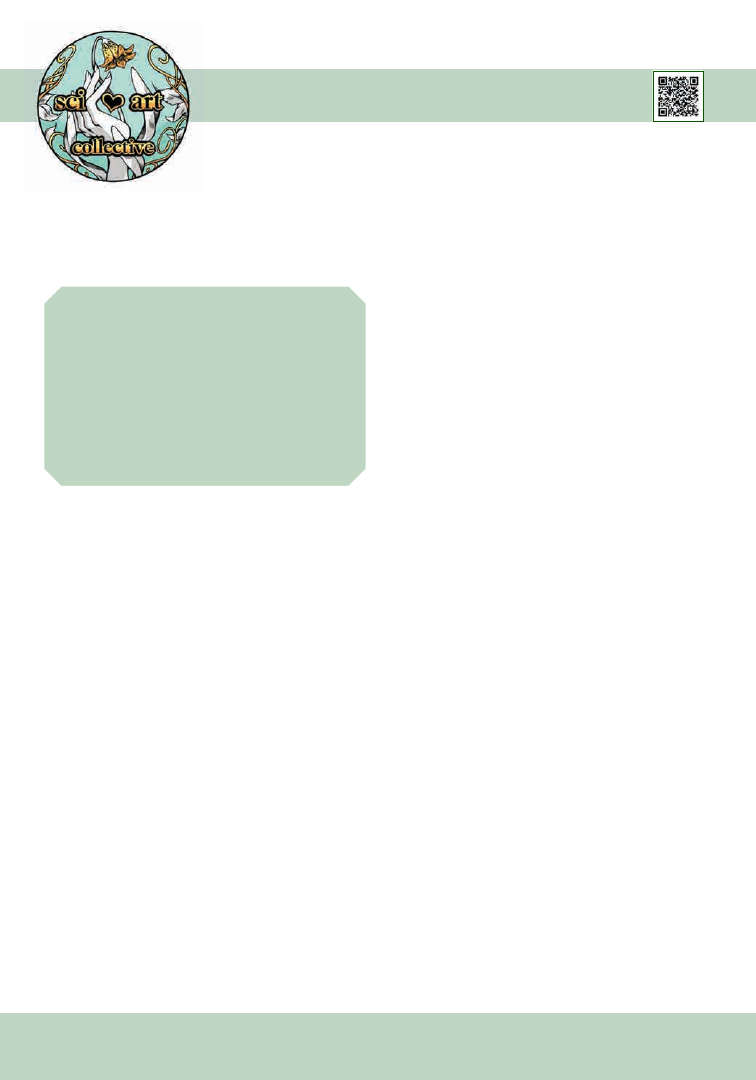

Figure 1. Botanical-inspired art and science exhibited during the “Where We Will Grow Exhibit.” (A) A portion of the exhibit

pairing student art pieces with a description of Elsie Slater and her works, specimens, and art; (B) an example of Elsie’s art pieces;

(C) a Porophyllum scoparium specimen (UTEP 6646) used as art inspiration in part D; (D) art piece by Julyet Carillo, using sev-

eral species (UTEP 6646, 6696, 6649) showcased in the exhibit; (E) tour stop at the purple prickly pear (Opuntia macrocentra) in

the gardens, connecting living specimens to Elsie’s specimen (UTEP 6668). Photos courtesy of the Centennial Museum (A and B).

178

The resulting exhibit, “Where We Will Grow: Elsie

Slater, Plants, and Art,” combined Elsie’s botanical

specimens, art, and writings with diverse pieces

of contemporary student art. Curators selected

specimens from Elsie’s collections that were used

by students, represented in Elsie’s art or both

(i.e., Figure 1C and D). To draw cohesion with

the exhibit and living plants, patrons toured

the museum’s Chihuahuan Desert Gardens via

a self-guided tour app that linked living and

herbarium specimens. To choose the stops, we

cross referenced a list of specimens used by the

art students and species represented by Elsie’s

collections to species available in the Centennial

Gardens (i.e., Figure 1D and E). At each stop,

patrons scanned a QR code and viewed a specimen

collected by Elsie, its locality information, and a

few facts about the species. As a result, patrons

could view the same species in multiple contexts,

from the past, present, and future, through art, as

well as historical and living specimens.

The digital exhibit can be accessed at https://www.

utep.edu/centennial-museum/museum/past-

exhibits/where-we-will-grow.html.

REFERENCES

Flannery, M. C. 2013. The herbarium as muse: plant

specimens as inspiration. Biology International 53: 23-34.

Soltis, P. S. 2017. Digitization of herbaria enables novel

research. American Journal of Botany 104: 1281-1284.

179

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

Alice V. Pierce

1,2,5,

Ian C. Anderson

1,3

Neelima R. Sinha

4

J. Grey Monroe

1

1

Department of Plant Biology, University of California,

Davis, Davis, CA, USA, 95616

2

Department of Plant Sciences, University of California,

Davis, Davis, CA, USA, 95616

3

Integrative Genetics and Genomics Graduate Group, Uni-

versity of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA, 95616

4

Plant Biology Graduate Group, University of California,

Davis, Davis, CA, USA, 95616

5

Author for correspondence: avpierce@ucdavis.edu

ABSTRACT

Especially in recent decades, plant scientists

have had to develop new skill sets, becoming

statisticians, bioinformaticians, evolutionary

ecologists, visual artists, as well as experts in many

fields of biology. In regard to visual arts, botanists

have a long history of collecting plant specimens

for herbariums across the globe to showcase plant

diversity and through illustrations, they raise

awareness of the vast ecological importance of

plants in their diverse habitats. With botanical art,

plant scientists increase the public appreciation of

plant diversity and provide access to diversity in

regions where some of these plants had never been

seen. Now, with huge online repositories of digital

plant pictures, DNA/RNA sequencing, ChIP-seq,

metabolomics, and proteomic/crystallography

data, plant scientists have increased the ways to

catalog plant diversity at the molecular level, and

further increased the access of these resources

Celebrating Plant Diversity through Art

to fellow scientists. In this series of illustrations,

and through a modern digital twist of botanical

art, we hope to celebrate the progress made by

plant scientists around the world to accelerate our

understanding of plant evolution and diversity

and highlight a promising avenue for scientific

illustration to play a role in depicting fundamental

plant biological concepts and molecular diversity.

KEYWORDS

botanists, plant diversity, plant scientists, science

art

New technologies, such as DNA/RNA

sequencing, ChIP-seq, metabolite profiling, X-ray

crystallography, and others, have expanded our

methods for cataloging plant diversity by allowing

scientists to study plants at the molecular level.

In Figure 1, we celebrate the novel and impactful

efforts made by plant scientists to catalog

plant diversity across scales—from proteins to

Petunias. Understanding the diverse interactions

occurring at the molecular, cellular, organismal,

and environmental levels accelerates our

understanding of plant diversity and adaptation to

their environments.

Next to the chromatin, mRNA transcripts are being

subjected to RNA interference (F). At the top is an

homage to the petunia experiment where RNAi

was first discovered (G). Some of these transcripts,

however, can be transcribed by ribosomes and

become proteins (H). Many proteins interact at

the cellular level and work together to carry out

180

Figure 1. Several discoveries have revealed how plants interact and respond to their envi-

ronment. See the text of this article for further explanation.

a wide range of biological functions, including

transcription, translation, signaling, metabolic

processes (I), and carbon fixation (J).

On a larger scale, we see how cell types that have

differential gene expression patterns and vary in

protein populations can come together to form

tissues, such as in the stomata-epidermal cell

layer (K) and the leaf cross-section (L). These cells

interact with each other to communicate with

themselves and the environment to respond to

stimuli they might encounter.

Plants can respond to hormones such as auxin,

ethylene, and salicylic acid (M), which play a

crucial role in the diverse interactions occurring

within and between plants. Hormones regulate

181

plant growth, development, and response to

environmental and pathogen stress.

On the bottom, we see variation in tomato leaf

shape with age, known as heteroblasty (N). A

subset of phenotypic variation of developmental

traits allows plants to adapt and interact with their

environment differently, potentially providing an

advantage in various ecological niches depending

on the circumstances.

In addition to interacting with their abiotic

environment, plants interact with other

organisms. Understanding the interactions of

plants with other organisms such as microbes (O)

or pollinators (P) is critical for understanding the

role of plants in their ecosystem.

Continuing to catalog plant diversity at the

molecular, cellular, and environmental levels is

crucial to understanding and appreciating how

plants interact with their environment, furthering

our understanding of how plants have contributed

to the diversity of life, and accelerating efforts to

conserve plant species in a rapidly changing world.

182

From the P SB Special I ssue on Art in the Botanical Sciences

Brazilian Botanists Flirting with Arts:

Valuing the Multicultural Heritage

Lucas C. Marinho

1

Anderson dos S. Portugal

2

Vinícius dos S. Moraes

3

Marcelo G. Santos

2

Suzana Ursi

4

1

Universidade Federal do Maranhão, Departamento de

Biologia, Avenida dos Portugueses 1966, Bacanga, 65080-

805, São Luís, MA, Brasil.

2

Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, Faculdade de

Formação de Professores, Laboratório de Biodiversidade,

Rua Dr. Francisco Portela 1470, Patronato, 24435-005,

São Gonçalo, RJ, Brasil.

3

Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Laboratório de Inovações em

Terapias, Ensino e Bioprodutos, Avenida Brasil, 4365,

Manguinhos, 21045-900, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil.

4

Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Biociências, De-

partamento de Botânica, Rua do Matão 277, Cidade Uni-

versitária, 05508-090, São Paulo, SP, Brasil.

5

Author for correspondence: lc.marinho@ufma.br

Plants have always been a source of inspiration

for many artists, and Botany often resorts to them

so that plants “live” eternally—as is expected—in

artistic works. And the plants, what can they “tell”

us about these humans who try to understand them

using Science and Art? Brazilian literature brings

rich examples in which plants are the protagonists

(see Clarice Lispector or Ana Martins Marques).

In the book O pensamento vegetal: a literatura e as

plantas (“Plant thought: literature and plants” in

free translation), Evando Nascimento, a Brazilian

writer, highlighted the relationship between

literary text and the floristic universe at the 19th

International Literary Festival of Paraty (Flip).

In this edition, the focus was on “Nhe’éry,” the

Atlantic Forest as named by the Guarani, one of

the many native peoples of Brazil.

Initiatives focusing on this powerful Art–Botany

relationship are still germinating in Brazil

(following “ArtScience Manifesto”; see Bernstein

et al., 2011), with some botanists and teachers

building upon the multisensory and poetic

experience created by plants and the world. It

is clear that, even though sparsely distributed

throughout Brazilian history, there have been

other non-scientific artistic initiatives between art

and plants. But here, we present some of the Art

and Botany (as a science) initiatives and, especially,

contextualize the complex cultural interplay that

shaped these two areas in Brazil.

COLONIAL HERITAGE

The arrival of Europeans represented a breaking

point in how art was seen and produced in Brazil.

However, there is a rich recorded Brazilian Pre-

Cabraline Art (in reference to the Portuguese

navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral, the “discoverer” of

Brazil), represented by cave painting, sculptures,

and ceramics. Amazonian ceramics are probably

the best-known artistic manifestations of

Brazilian Pre-Cabraline Art (Prous, 2007). Prior

to colonial contact, Indigenous art was sovereign;

subsequently, other cultures, especially from the

African continent, also set out their point of view.

The art of the remaining Indigenous peoples is still

quite expressive in Brazil (for more, see examples

of Carmézia Emiliano and Uýra Sodoma). The

presence of artists (e.g., Thomas Ender and Johann

183

Moritz Rugendas) in the field expeditions to the

interior of Brazil showed the European vision of

the Brazilian flora, and everyday aspects for the

original people took on grandiose dimensions for

those who were unfamiliar with it.

Botany assumed the status of Scientia Amabilis

at the end of colonial period in Brazil, when the

knowledge about plants was seen as an important

social status with reverberations in architecture, in

gardens, and in the great scientific expeditions to

recognize the flora and the associated biodiversity.

National Botany Day in Brazil celebrates the

birthday of a Bavarian naturalist, Carl Friedrich von

Martius. Although this symbolic date highlights

how the European view is still hegemonic in

Brazilian Botany, it is impossible to ignore the

tremendous value of Martius’ legacy. Together

with Johann Baptist von Spix, Martius traveled

immense distances through Brazil between 1817

and 1820 throughout a variety of domains and

recorded all the floristic diversity they encountered

in the magnificent Flora Brasiliensis compendia.

They returned to Europe with a huge collection of

preserved biological samples and live specimens.

Two young Indigenous people from different

ethnicities in Brazil, Miranha and Juri, were also

taken to Europe and died some time later. The

story of how those people were integrated into

Martius and Spix’s expedition is still controversial

and has more than one version (Costa, 2019).

At the end of his life, Martius rejected the brutal

behavior of including people as collectibles, which

was sadly common among colonizing naturalists.

Martius and Spix produced valuable ethnographic

descriptions, and the masks collected by them in

Amazonia are an important record of symbolic

practices by Indigenous nations, many of them

now extinct (Santos, 2014).

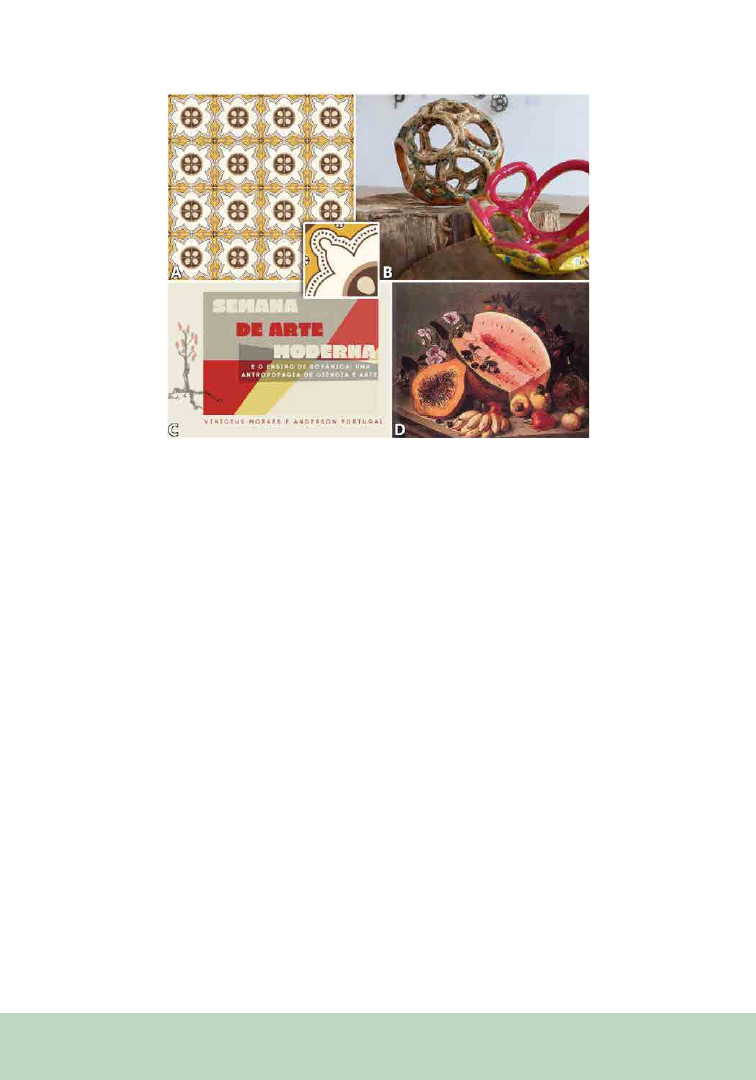

Gradually, not only was European culture brought

to Brazil, but also species in vivo or in graphic

representations, such as those that adorn the

Portuguese tiles, or azulejos, of northeastern Brazil

(Menezes et al., 2020). In this case, it was up to

Brazilians to appreciate the Europeans’ paintings

of non-native plants without the feeling of cultural

identity (belonging) about the artifact or what it

represented (Silva et al., 2021).

Brazilian flora began to be included slowly in

art as part of sacred works and sculptures (e.g.,

Machado et al., 2018). At that time, art in general

was closely linked to Catholic productions, and

much of what was produced had underlying

tendencies. In this sense, a devaluation of the

arts produced by cultural groups that existed

in Brazil (such as that by Indigenous people) or

that were brought to Brazil (such as by Africans)

was inevitable, since until then these local groups

did not share the Christian faith. Although the

quality and historical value contained in the

Portuguese azulejos and sacred sculptures are

invaluable, the presence of plants is linked to the

technical character, as part of the work, and not as

something to be felt (Figure 1).

Contrary to the visual arts, music and dance had

already been impacted by the presence of different

cultures on Brazilian land. Orality carried out

information about plants from north to south of

the country. For example, in Samba or Capoeira

(a dance/fight created by Brazilians of African

descent) songs, the use of native plants in the

production of percussive instruments and rituals

is common (Hartmann et al., 2023). The fact is

that, although the Brazilian population of the

colonial period was composed of many people—

it is important to highlight that Indigenous and

Africans were composed of countless different

ethnic groups, and each one had its own way

of seeing art and plants—the contribution for

“botany and art” was unbalanced.

Decolonization Movements

In 1922, a great artistic exhibition called “Semana

de Arte Moderna (SAM)” took place in São

Paulo. Organized by artists and intellectuals,

the movement suggested breaking up with

artistic European traditions of the time. SAM is

184