Pinguicula - the ButterwortsCarnivorous Plants / Insectivorous Plants

1. Here we see a butterwort, Pinguicula lutea, in its native habitat near Jacksonville, Florida. Pinguicula lutea occurs in sunny, open, wet areas throughout the southeastern U.S. Although butterworts have leaves and therefore trapping mechanisms that look nothing like those of the bladderworts (Utricularia), the two belong to the same family (Lentibulariaceae). Pinguicula bears one or two flowers at the end of a long stalk. 2. The leaves of Pinguicular lutea, seen up close, bear short hairs, (seen at the base of the lower leaf) which secrete sticky mucilage. Invisible in the shiny surface of the picture are tiny round glad hairs that digest insects that are caught in the mucilage. 3. The leaves of Pinguicula are yellowish in color, which is probably the source of the common name butterwort. The trapping mechanism of Pinguicula is a simple one. Insects become stuck in the sticky mucilage (which they may mistake for water or nectar). When an insect becomes stuck on the mucilage, the edge of the leaf slowly rolls over. The leaves never completely close. When the insect is digested, the leaf edges unroll and the leaf becomes more nearly flat.  4. The flowers of Pinguicula lutea are bright yellow. This color is attractive to bees. A bee could fit easily into the wider part of the flower of Pinguicula lutea. There is a small pointed tip on the flower, the spur (at left), which contains a droplet of nectar. A bee, properly oriented within the flower, could feed on the nectar if it has a long tongue. 5. Here are the leaves of Pinguicula caerulea, seen from the above. The bases of three flower stalks can be seen. Pinguicula caerulea occurs in the southeastern United States. 6. The flowers of Pinguicula caerulea are bluish-purple (the word caerulea means "sky-blue" in Latin). Here one flower is seen from the front, one from the side. Notice the small spur on the flower seen in side view. As with Pinguicula lutea, the flowers of Pinguicula caerulea are wide enough to admit a bee, and a long-tongued bee can, when it fully enters the flower, suck nectar from the spur. The flower of Pinguicula caerulea, seen from the front, features deep blue-purple veins on a white background. Patterns like this tend to be associated with be pollination. Where they are, such patterns are called guidelines, because bees are programmed to follow the direction of the veins, which lead them into a flower.     8. A section through a flower of Pinguicula caerulea shows the passage from outside to inside. The furry lump on the lower side of the throat evidently is a signal to a bee that it is on its way toward nectar, and tells it which is the lower side of the flower. If a crawled into the flower with the fury lump below, its back would be contacted by the anthers, which dust pollen on its back (an indentation on the upper part of the tube of the flower, on its upper side) or by the flower's stigma, which picks up pollen. Then a long-tongued bee could get nectar from the spur, which is too narrow for a bee's head but not its tongue.  9. The flower of Pinguicula caudata, seen from the front. The bright pink color suggests a pollinator other than bees. For example, butterflies are attracted to flowers with this color. The name "caudata" means "tailed," and refers to the fact that the spur is very long in flowers of this Pinguicula (spur not shown in this picture). The tongues of most insects cannot reach nectar in a long spur, but tongues of butterflies can. A section of the flower of Pinguicula caudata shows that the long nectar spur (less than half its length shown in this picture) is white inside, whereas the face of the flower is pink. Notice the two curving stamens (the pollen-bearing anthers at their tips) and the ovary, tipped by its pollen-collecting stigma, between them. The stamens and ovary are at the throat of the flower. In flowers pollinated by butterflies, stamens and stigmas tend to be at the throat of a flower, so that the pollen transfer can occur on a butterfly's head at the same time that the butterfly reaches its long tongue into the narrow part of a flower, at the bottom of which lies nectar. Pinguicula macroceras from northern California isn't a conspicuous plant. A butterwort when not in flower can be identified by its sticky yellowish leaves and by its habitat--acid areas that are wet throughout the year. Butterwort plants are perennials, living for several years.

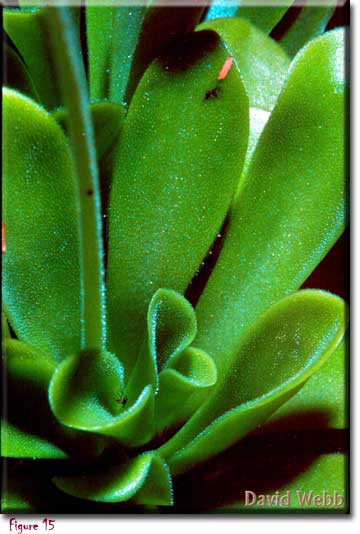

The plant that most closely resembles fly paper is Pinguicula (butterwort). In Michigan, Pinguicula vulgaris (Figure 12 above) occurs on the rocky shores of Lake Superior and is so rare that it is protected by law. You should check your own state for similar protected species as these occupy a rather narrow range of habitats. In Pinguicula, the leaves are all at the base of the plant, oval to nearly round, and often curled up at the edges. The upper surface of the plant is continuously sticky, and tiny flies like mosquitoes, gnats, and midges readily adhere to the surface (Figure 13). There are two kinds of glands on the surface of the leaf (Figure 14). The stalked glands are the sticky ones and trap the insect. The short, surface glands provide the digestive enzymes, including phosphatases, proteases, and ribonuclease, and later resorb the digested material (Heslop-Harrison 1978).  Pinguicula grandiflora can produce one new leaf about every five days, resulting in a total of 400 cm2 of catching surface by the end of the growing season (Heslop-Harrison 1978). In addition to insects, butterworts also make use of nutrients in pollen trapped on their sticky leaves (Heslop-Harrison 1978).

Ca. 80 Listed Species |