IN THIS ISSUE...

SUMMER 2023 VOLUME 69 NUMBER 2

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

155 Years of Botany at Emporia State

University: A Case Study of College

Botany in the U.S.... p. 92

Meet the new student representative,

Josh Felton! ... p. 141

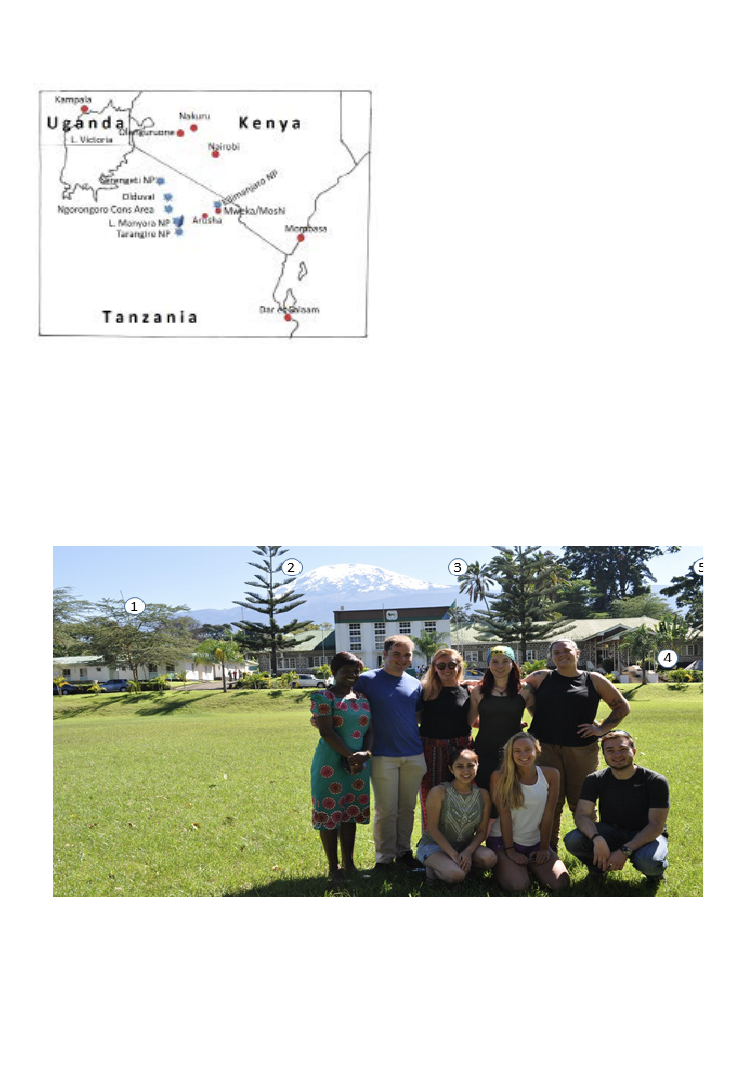

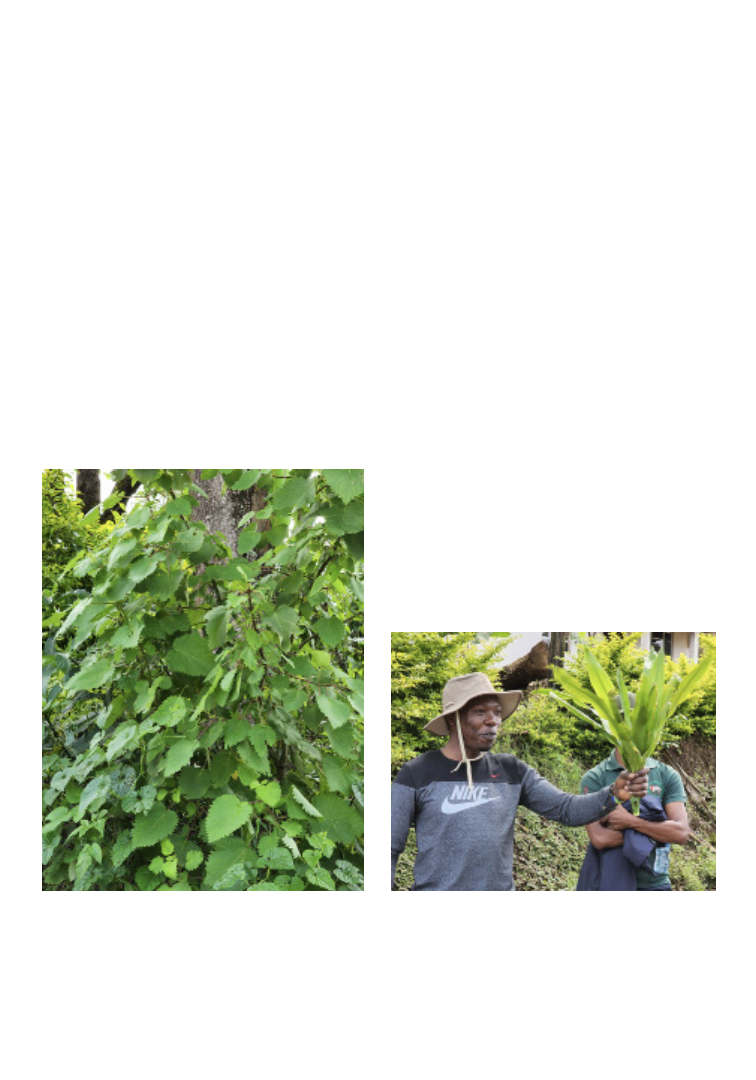

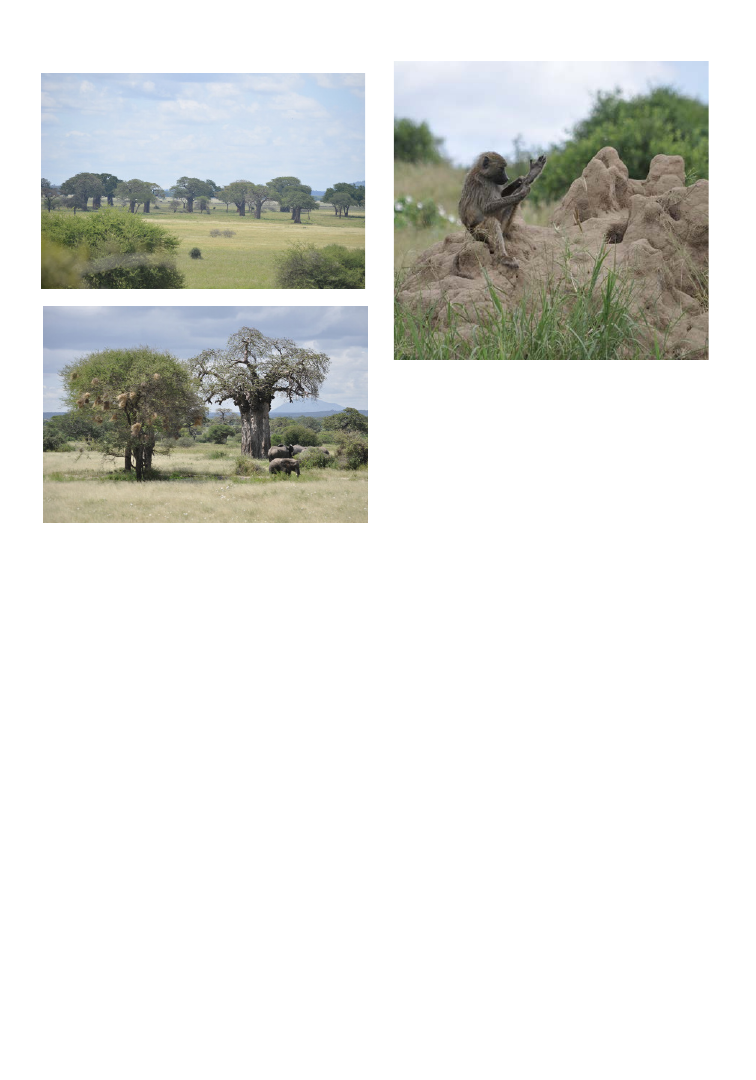

Travels in Tanzania with North

American Undergraduates: A Botanical

Safari...p. 114

Summer 2023 Volume 69 Number 2

FROM the EDITOR

Greetings,

It’s summer in Omaha, which means college baseball games, afternoon

thunderstorms, and incoming undergraduate advising. At my institution, at least,

it is rare to find a first-year student who knows they want to pursue a career in

botany. It can be a struggle to recruit and develop potential young botanists and

the landscape for botanical education has certainly undergone significant changes.

In this issue, you will find a case study of Botany as a discipline at Emporia State

University that discusses some of these challenges and changes, both historical and

recent. We also include an article describing a travel course which seeks to introduce

botany to students who are more focused on zoology. In this summer issue, you will

also find resources that may be helpful for navigating Botany 2023.

I hope to see many of you there!

Sincerely,

PSB 69 (2) 2023

68

68

SOCIETY NEWS

BSA Emerging Leader Award

The Emerging Leader Award of the Botanical Society of America is given annually in recognition

of creative and influential scholarship as well as impact in any area of botany reflecting the breadth

of BSA. Awardees have outstanding accomplishments and also have demonstrated exceptional

promise for future accomplishments in basic research, education, public policy, exceptional service

to the professional botanical community, or a combination of these categories.

Botanical Society of America’s

Award Winners (Part 1)

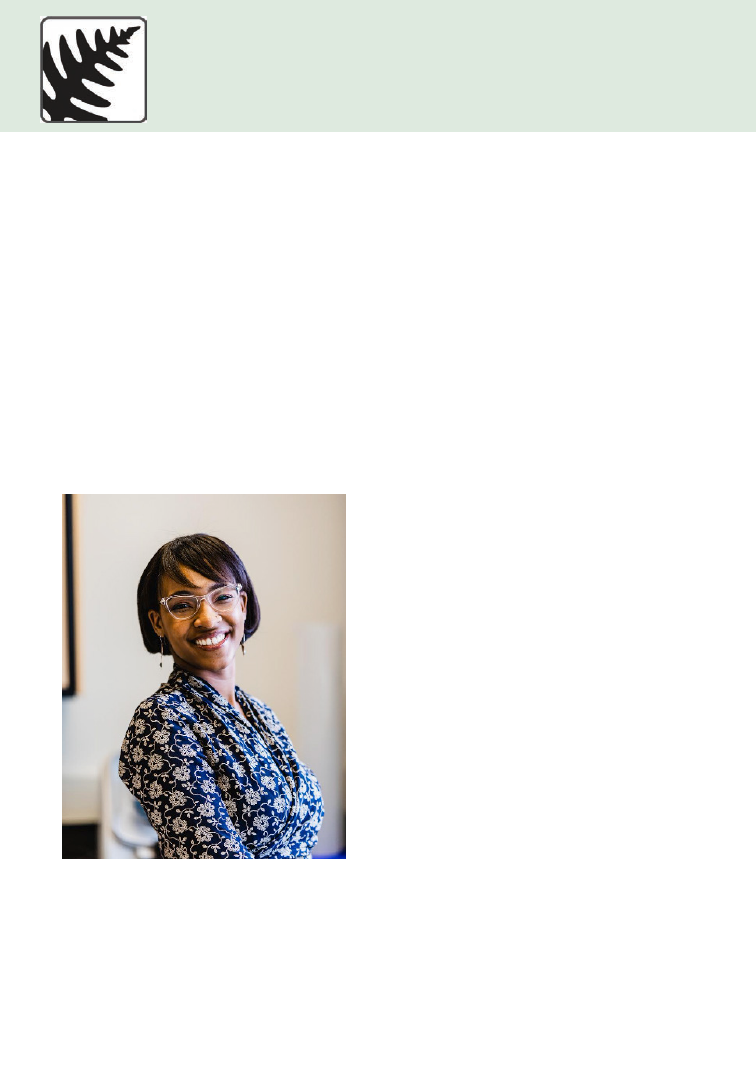

DR. JOYCE G. ONYENEDUM

CORNELL UNIVERSITY

Dr. Joyce Onyenedum is currently

Assistant Professor of Plant Evolution in

the Liberty Hyde Bailey Hortorium at

Cornell University. She earned a bachelor’s

degree in plant sciences from Cornell and

a doctorate in integrative biology from

the University of California, Berkeley. The

fundamental question driving her research is

understanding how plants climb. She studies

patterns through classical plant anatomy,

morphology, molecular systematics,

and statistical phylogenetic comparative

methods; she complements these findings

with an understanding of the developmental,

cell, and molecular processes that shape

the climbing habit in disparate lineages.

This integrative approach allows her to link

macroevolutionary patterns to fine-scale

mechanistic processes, thus uncovering the

evolution of development (evo-devo) of

climbing plants.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

69

Charles Edwin Bessey Teaching Award

(BSA in association with the Teaching Section and Education Committee)

Dr. Cynthia Jones, University of Connecticut

Dr. Eddie Watkins, Colgate University

Donald R. Kaplan Memorial Lecture

This award was created to promote research in plant comparative morphology, the Kaplan family

has established an endowed fund, administered through the Botanical Society of America, to

support the Ph.D. research of graduate students in this area.

Erika Edwards, Yale University

The Grady L. and Barbara D. Webster Structural Botany

Publication Award

This award was established in 2006 by Dr. Barbara D. Webster, Grady’s wife, and Dr. Susan V.

Webster, his daughter, to honor the life and work of Dr. Grady L. Webster. After Barbara’s passing

in 2018, the award was renamed to recognize her contributions to this field of study. The American

Society of Plant Taxonomists and the Botanical Society of America are pleased to join together in

honoring both Grady and Barbara Webster. In odd years, the BSA gives out this award and in even

years, the award is provided by the ASPT.

Alberto Echeverría, Emilio Petrone-Mendoza, Alí Segovia-Rivas, Víctor A. Figueroa-

Abundiz, and Mark E. Olson

The vessel wall thickness–vessel diameter relationship across woody angiosperms

American Journal of Botany, April 2022 109: 856-873

The BSA Developing Nations Travel Grants

Rafael Acuña-Castillo, Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

Tami C. Cacossi, UNICAMP, Brazil

Idowu Obisesan, Bowen University Iwo, Nigeria

Malka Saba, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Jayani Wathukarage, Department of Agriculture, Sri Lanka and University of the Philippines,

Diliman

PSB 69 (2) 2023

70

The BSA Professional Member Travel Grants

Ana Andruchow-Colombo, University of Kansas

Nina Baghai-Riding, Delta State University

Israel L. Cunha Neto, Cornell University

Jessamine Finch, Native Plant Trust & Framingham State University

Julia Gerasimova, Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt

Margaret Hanes, Eastern Michigan University

Adriana I. Hernandez, California Academy of Sciences

Pankaj Kumar Ph.D., FLS, Texas Tech University, Department of Plant and Soil Science

Francesco Martini, Trinity College Dublin

Elizabeth McCarthy, SUNY Cortland

BSA Public Policy Award

The Public Policy Award was established in 2012 to support the development of tomorrow’s leaders

and a better understanding of this critical area.

Katherine T. Charton, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Lauren M. Orton, Sauk Valley Community College

Botanical Advocacy and Service Grant

This award organized by the Environmental and Public Policy Committees of BSA and ASPT

aims to support local efforts that contribute to shaping public policy on issues relevant to plant

sciences. To learn more about the winning projects, go to https://botany.org/home/awards/spe-

cial-funds-and-awards/botany-advocacy-leadership-grant.html.

Zeta Phi Beta Sorority, Inc State of Hawaii/New Mexico State Social Action Coordinator:

Maya L. Shamsid-Deen

For the proposal: Zeta Day at City Council: Social Action for Integrative Botanical Education,

Access to Land, & Food Sovereignty

PSB 69 (2) 2023

71

AWARDS FOR ESTABLISHED SCIENTISTS

GIVEN BY THE SECTIONS

Samuel Noel Postlethwait Award (Teaching Section)

The Samuel Noel Postlethwait Award is given for outstanding service to the BSA Teaching Section.

Janelle M. Burke, Howard University

AWARDS FOR EARLY CAREER SCIENTISTS

AJB Synthesis Papers and Prize

The AJB Synthesis Prize is intended to showcase early-career scientists and to highlight their unique

perspectives on a research area or question, summarizing recent work and providing new insights

that advance the field. The Prize comes with a $2000 award and recognition at the BSA Awards Cer-

emony at the Botany Conference. This is the first year of this award.

Dr. Liming Cai, University of Texas at Austin, for her article “Rethinking convergence in

plant parasitism through the lens of molecular and population genetic processes,” 2023, AJB

110: e16174. (To read more about Dr. Cai, see the Publications Corner article in this issue.)

AWARDS FOR STUDENTS

Donald R. Kaplan Dissertation Award in

Comparative Morphology

This award was created to promote research in plant comparative morphology, the Kaplan family

has established an endowed fund, administered through the Botanical Society of America, to

support the Ph.D. research of graduate students in this area.

Haylee Nedblake, University of Kansas

For the Proposal: Evolution of bee-exclusionary corolla width differences in Penstemon

PSB 69 (2) 2023

72

Graduate Student Dissertation Award in Phylogenetic

Comparative Plant Biology

This award supports the Ph.D. research of graduate students in the area of comparative plant

biology, broadly speaking, from genome to whole organism. To learn more about this award click

here.

Zachary Muscavitch, University of Connecticut

For the Proposal: The evolutionary dynamics of fog lichen symbionts: going global

The BSA Graduate Student Research Award including the

J. S. Karling Award

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards support graduate student research and are made

on the basis of research proposals and letters of recommendations. Within the award group is

the Karling Graduate Student Research Award. This award was instituted by the Society in 1997

with funds derived through a generous gift from the estate of the eminent mycologist, John Sidney

Karling (1897-1994), and supports and promotes graduate student research in the botanical sciences.

The J. S. Karling Graduate Student Research Award

Jordan Argrett, University of Georgia

For the Proposal: Stealing from the rich to give to the poor: Are hemiparasitic plants the

“Robinhood” of sub-alpine communities?

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards

Anna Becker, University of Florida

For the Proposal: The evolution of Hawaiian blueberries

Akriti Bhattarai, University of Connecticut

For the Proposal: Exploring the genetic mechanisms of white pine blister rust disease

resistance in whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) and Siberian pine (P. sibirica)

Ryan Carlson, University of Minnesota Duluth

For the Proposal: Resolving euphrasia taxonomy in Minnesota

Brendan Connolly, Northwestern University and The Chicago Botanic Garden

For the Proposal: Not all pollinators are created equal: The effects of differences in pollination

efficiency on plant genetic diversity and reproductive success

PSB 69 (2) 2023

73

Alexander Damian-Parizaca, University of Wisconsin-Madison

For the Proposal: Evolution, Taxonomy and pollination of New World Vanilla (Orchidaceae)

Anthony Dant, University of Arizona

For the Proposal: Beyond sidewalks: using a dynamic urban classification system to study the

evolution of an invasive plant

Melissa Duda, Northwestern University

For the Proposal: Using reproductive biology and ecological niche models to predict the

potential impact of hybridization in rare species

Caroline Edwards, Indiana University

For the Proposal: The spatial scale and environmental drivers of local adaptation in Viola

pubescens

Emma Fetterly, Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden

For the Proposal: Understanding biotic and abiotic drivers of floral color polymorphism in

Castilleja coccinea to inform restoration in a changing climate

Clayton W. Hale, University of Georgia

For the Proposal: Left in the shade: understanding the impacts of phenological mismatch

between overstory leaf out and understory herbs

Brooke Kern, University of Minnesota

For the Proposal: Is low hybrid fitness driving selection for increased reproductive isolation

between Clarkia xantiana subspecies?

Ashmita Khanal, Texas Tech University

For the Proposal: Unravelling the genetic basis of sex chromosome evolution in Black

Willows (Salix nigra Marshall)

Izai Kikuchi, University of British Columbia

For the Proposal: Reconstructing the evolution of mycoheterotrophy in Gentianaceae and

Dioscoreales using nuclear phylogenomics

G Young Kim, University of Connecticut

For the Proposal: Facultative CAM (Crassulacean Acid Metabolism) photosynthesis in

Native Hawaiian Peperomia

Kira Lindelof, North Carolina State University

For the Proposal: Applied conservation genetics: GBS and building a genetic inventory for

the recovery of Houstonia montana, an imperiled high-elevation, southern Appalachian

endemic

PSB 69 (2) 2023

74

Amee Maurice, University of Connecticut

For the Proposal: Molecular mechanisms of white pine blister rust disease resistance among

the threatened whitebark pines

Hannah McConnell, University of Washington

For the Proposal: Using the model fern Ceratopteris richardii to investigate genes regulated

by LEAFY orthologs

María de Jesús Méndez Aguilar, Autonomous University of Yucatan

For the Proposal: Populational structure of the traditional Chaya (Cnidoscolus aconitifolius,

Euphorbiaceae) used by Mayan communities in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico

Thomas H. Murphy, University of Florida

For the Proposal: Linking morphological and niche evolution in a ubiquitous neotropical

climber

Rodrigo Nicolao, Universidade Federal de Pelotas

For the Proposal: The role of hybridization in the evolution of the Southeastern South

American wild potatoes (Solanum ser. Commersoniana, Solanaceae)

Diego Paredes-Burneo, Louisiana State University

For the Proposal: The role of the Amotape-Huancabamba zone on the diversification of the

high-Andean flora: a case study of the genus Brachyotum (Melastomataceae)

Seth J. Raynor, University of Colorado Boulder

For the Proposal: Lichens of the Indian Peaks Wilderness, towards a complete state inventory

Senna Robeson, University of Chicago

For the Proposal: Seeking the source of geographic range shifts in tarflowers (Bejaria, Ericaceae)

Katie Kobara Sanbonmatsu, Texas A&M University

For the Proposal: Phylogenetics and biogeography of Macromitrioideae (Orthotrichaceae): A

diverse but understudied group of mosses

Parikrama Sapkota (Pari), University of Texas at El Paso

For the Proposal: Unraveling above-belowground interactions that support restoration of

dryland plants communities

Rory Schiafo, Northwestern University and Chicago Botanic Garden

For the Proposal: Understanding the role of light availability and species’ characteristics for

driving priority effects in oak woodland plant communities

Rachel Tageant, Claremont Graduate University

For the Proposal: A floristic inventory of the Owens River Headwater Area, Mono County, CA

PSB 69 (2) 2023

75

Rina Talaba, Northwestern University

For the Proposal: Investigating the differences of Cirsium pitcheri’s floral scent according to

the predation of novel weevil, Larinus planus

Daniel Tucker, University of Victoria

For the Proposal: Magic carpets of the canopy: the role of epiphytic bryophyte functional

structure in driving hydrologic ecosystem processes in a tropical montane cloud forest

Selena Vengco, Claremont Graduate University

For the Proposal: Conservation genetics and the maintenance of flower color polymorphisms

in a non-model system of Erythranthe discolor (Phrymaceae)

Mari Wilson, University of British Columbia

For the Proposal: Comparative transcriptomic analysis of mycoheterotrophy in fern

gametophytes

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards support undergraduate student research and

are made on the basis of research proposals and letters of recommendation.

Melanie Beaudin, Carleton University

For the Proposal: Genetic diversity and population structure of a disjunct Opuntia fragilis

population

Max Gray, University of British Columbia

For the Proposal: Testing the pervasiveness of MITE-induced apomixis in Asteraceae

Kaitlin Henry, Bucknell University

For the Proposal: Chemical analysis of extrafloral nectar in western Australian Solanum

tudununggae (Solanaceae) to explore possible ant-plant relationships

Jonathan Le, University of California, Irvine

For the Proposal: Mapping nutrient localization throughout Drosera capensis digestion using

MALDI-MSI

Samuel Monger, Auburn University in Montgomery

For the Proposal: Identification of kudzu-associated soil microbes - a first step towards

developing more successful restoration techniques

Zach Smith, University of Wisconsin-Madison

For the Proposal: Morphological and physiological adaptation in an ancient plant lineage

PSB 69 (2) 2023

76

The BSA Young Botanist Awards

The purpose of these awards is to offer individual recognition to outstanding graduating seniors

in the plant sciences and to encourage their participation in the Botanical Society of America.

Fae Bramblepelt, The University of Alabama, Advisor: Michael McKain

Gurleen Chana, University of Guelph, Advisor: Christina Caruso

Sam Fuss, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Erin Grady, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, Advisor: Natalie Love

Wolfgang Graff, Miami University, Advisor: Richard Moore

William Gregor, Miami University, Advisor: Richard Moore

Hanna Hickey, University of Guelph, Advisor: Christina Caruso

Ellie Hollo, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Megan Keyser, Miami University, Advisor: Richard Moore

Henry Lagasse, Trinity College, Advisor: Nikisha Patel

Claire Marino, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine and Tanisha Williams

Taylor Michael, Pittsburg State University, Advisor: Neil Snow

Aadia Moseley-McCloud, Howard University, Advisor: Janelle Burke

Celina Patiño, Weber State University, Advisor: James Cohen

Sam Pelletier, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Dominique Pham, University of Richmond, Advisor: Carrie Wu

Sierra Sattler, South Dakota State University, Advisor: Maribeth Latvis

Rachel Savage, South Dakota State University, Advisor: Maribeth Latvis

Madeline Wickers, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine and Tanisha Williams

Matthew Yamamoto, Connecticut College, Advisor: Rachel Spicer

Noah Yawn, Auburn University, Advisor: Robert Boyd

Diamanda Zizis, Bucknell University, Advisor: Chris Martine and Tanisha Williams

PSB 69 (2) 2023

77

The BSA Student and PostDoc Travel Awards

Winners were selected by lottery

Sevyn Brothers

Claudenice H. Dalastra

Melissa A. Lehrer

Isabela Lima Borges

Carlos A. Maya-Lastra

Vernon I. Cheadle Student Travel Awards

(BSA in association with the Developmental and Structural Section)

This award was named in honor of the memory and work of Dr. Vernon I. Cheadle.

Arthur Leung, University of Toronto, Advisor: Rowan Sage

For the Presentation: Ultrastructural modifications facilitated the initial steps in the evolution

of C4 photosynthesis in Tribulus (Zygophyllaceae)

Oluwatobi Adekunle Oso, Yale University, Advisor: Professor Erika Edwards

For the Presentation: Origin and distribution of leaf teeth in temperate woody angiosperm flora.

AWARDS FOR STUDENTS - GIVEN BY THE SECTIONS

Southeastern Section Student Presentation Awards

The following winners were selected from the Association of Southeastern Biologists meeting that

took place at the end of March, 2023.

Southeastern Section Paper Presentation Award

Ben Brewer, Appalachian State University

Southeastern Section Poster Presentation Award

Elizabeth Companion, University of North Carolina Asheville

Mason McNair

Erika R. Moore-Pollard

Megan Nibbelink

Zach Smith

Tengxiang Wang

PSB 69 (2) 2023

78

STUDENT TRAVEL AWARDS

Developmental & Structural Section Student Travel Awards

Yesenia Madrigal B., Universidad de Antioquia (Colombia), Advisor: Natalia Pabón-Mora

For the Presentation: Assessment of the flowering genetic regulatory network in tropical

orchids with different lifeforms.

Deannah Neupert, Miami University, Advisor: Richard Moore

For the Presentation: The alteration to vegetative growth and gene expression supports the use

of a novel aerial bulbil in Mimulus gemmiparus for reproduction.

Ecological Section Student Travel Awards

Annie E. Meeder, California Polytechnic University, Advisor: Dr. Jenn Yost, For the

Presentation: Post-eradication transitions and dynamics of Santa Cruz Island vegetation

communities.

Charlotte Miranda, San Jose State University, Advisor: Benjamin Carter

For the Presentation: Soil generalist Erysimum capitatum shows differential adaptation to

serpentine soil of origin across a California latitudinal gradient

Shan Wong, Texas Tech University, Advisor: Jyotsna Sharma

For the Presentation: Disjunct populations of a hemi-epiphytic orchid (Vanilla trigonocarpa)

show segregation of mycorrhizal niches.

Genetics Section Student Travel Awards

Samantha Drewry, University of Memphis, Advisor: Jennifer Mandel

For the Presentation: Conservation genetics in the endangered whorled sunflower Helianthus

verticillatus (Asteraceae).

Elizabeth Uzezi Okinedo, University of Massachusetts Boston, Advisor: Brook Moyers

For the Presentation: Pleiotropy and adaptation in the silverleaf sunflower, Helianthus

argophyllus

Primarily Undergraduate Institution (PUI) Faculty and

Future Faculty Conference Awards

Sarah E. Allen, Penn State Altoona

Chloe Pak Drummond, Mount Holyoke College

PSB 69 (2) 2023

79

Elizabeth McCarthy, SUNY Cortland

Angela McDonnell, St. Cloud State University

Angela Walczyk, Gustavus Adolphus College

Phytochemical Section Student Travel Awards

Abigail McCoy, State University of New York at Cortland, Advisor: Dr. Elizabeth McCarthy

For the Proposal: Relaxed purifying selection is observed in genes at the branches of the

flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in Nicotiana species that do not produce anthocyanin

compared to those that do. Co-authors: Jacob Landis, Elizabeth McCarthy

Pteridological Section & American Fern Society

Student Travel Awards

Lacey E. Benson, San Jose State University, Advisor: Dr. Susan Lambrecht

For the Presentation: A morphometric analysis of western sword fern (Polystichum munitum)

pinnae and pinnae scales across the coast redwood forest ecological gradient.

You-Wun Hwang, National Tsing Hua University, Advisor: Li-Yaung Kuo

For the Presentation: Frond dimorphism in Tectaria ferns: trends of their foliar characteristics

and spore investment

@TorreyBotanical

www.torreybotanical.org

@TorreyBotanicalSociety

Torrey Botanical Society

THE OLDEST BOTANICAL SOCIETY IN THE AMERICAS

Field trips

held in the

NY/NJ/CT area

Journal of the Torrey

Botanical Society

free to publish

low open-access fees

Virtual lectures

watch our past

lectures on YouTube

Undergraduate,

graduate, and early

career fellowships

application deadline:

January 15

Since our founding in New York City in 1867, the

goals of the Torrey Botanical Society have

remained the same: to promote an interest in

botany, and to collect and diffuse information

on all topics relating to botany.

Staten Island, 1914

upstate NY, 2012

PSB 69 (2) 2023

80

Eric Puetz

South Dakota State University

Biological life has always fascinated me for

as long as I can remember. At a young age I

was exposed to Native tallgrass prairie species

of Eastern South Dakota. This landscape of

rolling prairie is home to the “Coteau des

Prairie” or “Prairie Coteau,” as described by

French explorers and the homeland of the

Lakota Sioux. This region is located within

one of the most endangered ecosystems on

the planet, Northern Tallgrass prairie, with

an estimated 2–14% of Native Tallgrass

prairie remaining. Conservation policy is

often intertwined with economic interests,

and this is especially true in South Dakota,

where tourism is a significant industry due to

its many natural beauties, including the Black

Hills, Badlands, and Missouri River. I am a

strong believer that biological conservation

of private and public lands is a matter of

national security, and this is linked directly

to public policy. As the impacts of climate

change, geopolitical instability, hunger,

and loss of ecosystem services threaten our

world’s growing population, conserving and

investing in our “biodiversity infrastructure”

will preserve our nation’s ability to provide

resources for future generations. To quote

the late author and naturalist Aldo Leopold,

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve

the integrity, stability, and beauty of the

biotic community. It is wrong when it tends

otherwise.” Preserving ecosystem services

in the face of climate change will require

substantial investment in scientific research,

public education, and advocacy.

In April 2022 I was a recipient of the 2022

Congressional Visits Day (CVD) Award and

had the honor of representing the Botanical

Society of America (BSA) and American

Society of Plant Taxonomists (ASPT).

Drawing on past hands-on experience and

ongoing research training at South Dakota

State University, I used my platform to

advocate for $11 billion in appropriations

for the National Science Foundation (NSF)

in support of scientific research, public

2022—2023 Congressional Visits

Day Remarks

Each year, the BSA Public Policy Committee awards two early-career botanists the opportunity to

attend the American Institute of Biological Sciences’ Congressional Visits Day. This event is hosted

by the Biological and Ecological Sciences Coalition, and recipients obtain first-hand experience

at the interface of science and public policy. The first day includes a half-day training session

on science funding and how to effectively communicate with policymakers provided by AIBS.

Participants then meet with their Congressional policymakers, during which they will advocate

for federal support of scientific research. This article details the experiences of this year’s recipients.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

81

education, and ecological conservation, using

a practical, no-nonsense approach valued in

South Dakota and the Midwest. The NSF’s FY

2023 budget request consisted of six themes:

climate and clean energy research, equity

for underserved communities, discovery

engine, emerging industries, research

infrastructure, and organizational excellence

agency operations/award management. This

experience introduced me to the world of

public policy and allowed me to develop

communication and advocacy skills necessary

for communicating with lawmakers. Despite

the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and

communicating virtually, this event opened

my eyes to the advancements NSF funding

provides in medicine, engineering, biological

sciences, and technology we use every day.

This event, which began with a two-day

communication bootcamp, allowed me to

further build my communication skills and

emphasized the importance of incorporating

my personal story in advocating for increased

NSF funding. Following the communications

bootcamp, three constituents and I met with

personnel from the offices of lawmakers from

South Dakota: Rep. Johnson, Sen. Rounds,

Sen. Thune; Montana: Rep. Rosendale,

Sen. Daines, Sen. Tester; and Minnesota:

Rep. Philips, Sen. Smith. Following the

communication bootcamp, my team members

and I formed a discussion plan of talking

points in relation to our personal stories,

which helped to form relationships during the

short meetings with lawmakers’ staff. Several

memorable moments from these interactions

include briefly speaking with Rep. Johnson,

who had a few moments to listen to our

message despite a busy schedule, and the

breakthrough moments with lawmakers’ staff

where our message was truly being absorbed

and the spark of a true connection was evident.

Bipartisan cooperation during times of stark

partisan political divide is vital to achieving

legislative success. My team and I experienced

strong bipartisan support from Democrat and

Republican lawmakers alike, and during the

fiscal year 2023 NSF funding was increased

by 12% to $9.9 billion. I cherish the memories

from this event, and having the opportunity

to use my voice to advocate for scientific

advancement was a profound experience.

LAUREN M. ORTON, PHD

Sauk Valley Community College

I am honored to be selected as a recipient of

the 2023 Botanical Society of America’s Public

Policy Award. As an early-career Professor of

Biology at Sauk Valley Community College

in Dixon, Illinois, one of my passions is to

advocate for STEM programs across the

higher educational spectrum. The trip to

Washington, DC, was an amazing opportunity

to express the importance of science, not only

from a research perspective, but also from

the unique perspective of community college

education. When we think of projects funded

by the National Science Foundation (NSF),

we can easily identify needs at research-

based universities, independent and non-

profit research organizations, and medical

PSB 69 (2) 2023

82

institutions. However, community colleges

and their diverse student bodies also benefit

greatly from NSF-funded programs that

provide research opportunities for 2- and

4-year undergraduate level students (Research

Experience for Undergraduate student

programs).

After arriving in our nation’s capitol, I had some

time to sightsee across the National Mall (one

of my favorite places). Advocacy, throughout

history, has found its voice on the Mall, and it

is a great source of inspiration. The following

day, our science communication bootcamp,

hosted by the American Institute for Biological

Sciences (AIBS), began at Southwestern

Universities Research Association’s downtown

DC conference facility. Dr. Jyotsna Pandey of

AIBS provided a wonderful bootcamp, and

we began by learning about the pillars of

communication and how to effectively share

our message. Often, scientists are perceived

as out of touch, and it can be a struggle to

express a technical message in ways that

resonate with our audience. Therefore, having

Jyotsna’s expertise in communicating with

our lawmakers was an invaluable learning

opportunity for me. With the tools we learned

during the day, we were able to begin crafting

a message that would be both informative

and persuasive while presenting the needs

of the scientific community through specific

examples in support of our positions.

Additionally, a panel of public policy experts

joined us to speak about their careers on The

Hill and with various federal organizations

dedicated to crafting public policy. Their

experience and advice were encouraging to

those of us seeking to expand our involvement

in science public policy.

That afternoon and continuing into the

morning of the second day, we learned about

the complexities of the federal budgeting

process. Already having an understanding

of organizational and municipal budgeting, I

was amazed by the funding challenges that the

federal government grapples with each fiscal

year. Discretionary funding, which includes

the NSF, is where we tend to hear of the

sweeping cuts in favor of increasing funding

in other areas. There is never an easy solution

when it comes to the budgeting process.

With this knowledge in hand, I began to

understand the approach to advocating for

funding of the NSF, and how to go about

effectively providing that information to

our lawmakers. That second afternoon we

worked with our assigned regional groups. As

a Midwest resident, I was partnered with my

fellow BSA Public Policy Awardee, Katherine

Charton from the University of Wisconsin,

Madison, and Dr. Rebecca Kauten of the Iowa

Lakeside Laboratory and University of Iowa.

I am so grateful to have been partnered with

Katherine and Rebecca, who are not only

wonderful colleagues, but passionate policy

advocates as well! We worked together to

craft a clear and concise message, and request

funding of the NSF at or above the current

level of $11.9 billion. Each team member

spoke to their own strengths and elaborated

on how NSF funding has positively impacted

their careers. Whether it was discussing the

concrete funding numbers and effect on

STEM workforce percentages, speaking to

the impact of NSF funding on the ability for

small and university-independent research

organizations to collect crucial data, or

advocating for educational opportunities made

possible by the NSF for underrepresented

student groups and community college science

programs, we devised a clear message for our

PSB 69 (2) 2023

83

lawmakers. This message was that the NSF is

the primary funding body for science, and

each of us has seen or personally experienced

the positive impact it provides—the NSF

needs your support!

The Congressional Visits Day was an absolute

whirlwind! Starting early in the morning, our

Midwest team traveled to Capitol Hill where

we had for our first meeting in Senator Ron

Johnson’s (R-WI) Hart Senate Building office.

With Jyotsna present to lend her expertise,

we spoke with members of Senator Johnson’s

staff and provided materials from AIBS to

support our request to fund the NSF at $11.9

billion. Although the meeting was brief, it

was informative and upbeat; also, despite

the busy schedules of the congressional staff

members, we were well received everywhere

we went. We bounced back and forth between

the Dirksen Senate Office Building, the

Longworth House Office Building and the

Hart Senate Office Building, meeting with

staff of Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI),

Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA), Senator Joni

Ernst (R-IA), Representative Mark Pocan

(D-WI), Representative Ashley Hinson (R-

IA), and Representative Lauren Underwood

(D-IL). To conclude the day, I met with staff

members of Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL)

and Senator Tammy Duckworth (D-IL) from

my home state of Illinois. Julie Palakovich

Carr, a current member of the Maryland

state legislature, former congressional staff

member, and AIBS associate, joined me to

provide her expertise on NSF funding. It was a

pleasure to speak with her regarding her time

on The Hill and her passion for meaningful

legislation as an elected official.

Overall, my experience was an unforgettable

one. It was a remarkable opportunity to not

only learn about the ins-and-outs of federal

funding and budgeting, but also lend my

voice in support of funding an organization

that is paramount in the scientific community

for financial backing of research. Both

large and small projects, undergraduate

and graduate student thesis research, non-

profit and independent research facility

projects, opportunities for students outside of

traditional research-based higher education

institutions, and so much more fall under the

purview of the NSF’s funding. Meeting with

our representatives keeps them informed of

what their constituency values and wants to

see supported. I hope more people engage

in public policy and speak up for positive

change. As a professor, one thing that was

particularly impactful from this opportunity

was sharing the experience with my students,

in real-time, thanks to social media. I was able

to update students of my journey by posting

to my educational social media channel and

engaging them in the civic process. It is my

hope that, through my example of advocacy,

they will find their voices and become involved

in the issues that matter most to them.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

84

84

PUBLICATIONS CORNER

It is with great pleasure that we mark the first

10 years of publication for Applications in Plant

Sciences. APPS was launched as an open access

journal in January 2013 with the intention of

being “a new source for sharing exciting and

innovative applications of new technologies

that have the potential to propel plant research

forward into the future,” according to the

journal’s first Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Theresa

Culley. The journal covers all areas of the plant

sciences, publishing novel protocols, software

notes, reviews, and application and genomic

resource articles, under the leadership of

current Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Briana Gross, and

Managing Editor Beth Parada, along with the

APPS editorial board.

We will be marking this milestone and

highlighting some of the remarkable papers

published over the past 10 years, including

several special themed issues, which have

helped to bring in talented early-career

and experienced researchers working

together as editors, reviewers, and authors.

Congratulations to all the dedicated people

who contribute to the journal and benefit

from reading the papers published!

Celebrating 10 Years of Publication

for

Applications in Plant Sciences

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF

BOTANY

SYNTHESIS PRIZE

We are delighted to announce that Dr.

Liming Cai, of the University of Texas

at Austin, is the winner of the first AJB

Synthesis Prize (https://botany.org/home/

awards/awards-for-early-career-scientists/

ajb-synthesis-papers-and-prize.html) for

her article “Rethinking convergence in plant

parasitism through the lens of molecular

and population genetic processes,” AJB 2023,

110: e16174. The Synthesis competition was

intended to showcase early-career scientists

and to highlight their unique perspectives on a

research area or question, summarizing recent

work and providing new insights that advance

the field. The Prize comes with a $2000 award

and recognition at the BSA Awards Ceremony

at the Botany Conference.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

85

Dr. Cai is currently a Stengl-Wyer Postdoctoral

Research Fellow at the University of Texas at

Austin focusing on the evolutionary genomics

and physiology of parasitic plants. She

received her doctoral degree in evolutionary

plant biology at Harvard University, and

her bachelor’s degree, with Honors, in Life

Sciences from Fudan University in Shanghai,

China. Her research combines natural history

and cutting-edge molecular methods to

gain a mechanistic understanding of how

plants live and evolve. She is exploring

how plant parasitism impacts the integrity

of mitochondrial function and mito-nuclear

interaction using genome sequencing,

respiratory physiology, and herbarium-

based approaches. Dr. Cai is a member of

the BSA’s Early Career Advisory Board and

has served on the Reviewing Editor Board

for Applications in Plant Sciences. She has

published numerous papers in peer-reviewed

journals and received much recognition and

many awards for her scholarship.

Dr. Cai was one of six early-career scientists

whose Synthesis papers were published in

AJB (https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

doi/toc/10.1002/(ISSN)1537-2197.synthesis).

CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL THE AUTHORS!

PSB 69 (2) 2023

86

The June issue of the American Journal of

Botany explores the theme of “Pollen as

the Link Between Floral Phenotype and

Fitness.” Guest editors Øystein H. Opedal,

Rocío Pérez-Barrales, Vinícius L. G. Brito,

Nathan Muchhala, Miquel Capó, and

Agnes Dellinger worked with contributors

to highlight research that provides new

insights into the relationships between pollen

production, presentation, flower morphology,

and pollination performance (e.g., pollen

deposition onto stigmas), the role of pollinators

in pollen transfer, and the consequences of

heterospecific pollen deposition. Several of

the studies demonstrate exciting experimental

and analytical approaches that should pave

the way for continued work addressing the

intriguing role of pollen in linking plant

phenotypes to reproductive fitness. A paper

in Applications in Plant Sciences forms part of

the current special issue and presents a new

pollen quantification technique that evaluates

the use of high-energy violet light for pollen

grain classification.

The May–June issue of Applications in Plant

Sciences explores “Emerging Methods in

Botanical DNA/RNA Extraction.” Guest

editors Richard Hodel, Ed McAssey, and

Nora Mitchell have curated a diverse group

of papers highlighting the current state

of knowledge in nucleic acid extractions,

including both the key challenges and creative

innovations that have been developed to

circumvent these challenges to address a

variety of exciting botanical questions. This

special issue provides a valuable resource

that will help readers to improve their own

protocols, expand their toolkits, and consider

additional research frontiers enabled by

nucleic acid data.

EXPLORE THE NEW

AJB/APPS SPECIAL ISSUES

See the full issue at:

https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

toc/21680450/2023/11/3

See the full issue at:

https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/

toc/15372197/2023/110/6.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

87

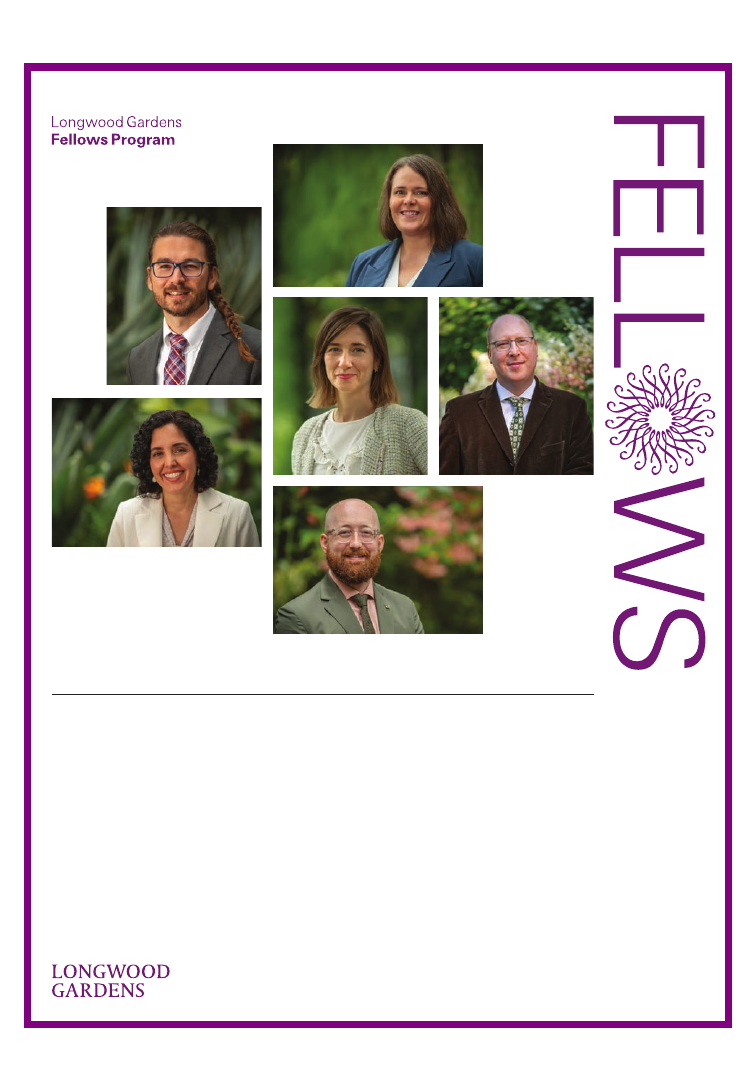

Do you aspire to lead a

horticultural institution

or business?

Are you passionate about

using your career to make

a positive global impact?

Your Path

to Leadership

Applications for the 2024–2025 cohort are

open through July 31. Learn more and apply

at longwoodgardens.org/fellows-program.

Congratulations

to our graduating

2022–2023

Longwood Fellows

Cohort. From top

left: Danny Cox,

Amanda Hannah,

Rae Vassar, Rama

Lopez-Rivera,

Anamari Mena, and

Ryan Gott, Ph.D.

The Fellows Program develops tomorrow’s leaders,

preparing them to successfully navigate pressing

challenges, develop thoughtful strategies, and lead

organizations that are equitable and sustainable.

During the fully funded, cohort-based residency,

Fellows engage in project-based learning that

allows them to hone their professional skills while

delving into issues relevant to the horticulture

industry today.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

88

Jacquelyn Gill is an associate professor of paleoecology at the University of Maine’s Climate

Change Institute. She is a paleoecologist and biogeographer, bringing the perspectives of

space and time to bear on questions in ecology and global change science. Her work takes

a community ecology approach to help understand how species and their interactions

have responded to interacting drivers (like climate change and extinction) through time.

She directs the BEAST Lab, which investigates 1) the legacies “biotic upheavals” like the

extinction of Pleistocene megafauna on vegetation, 2) biotic interactions and drivers of

landscape change on large spatiotemporal scales, 3) plant range dynamics and vulnerability to

climate change, and 4) what paleoecology, Indigenous archaeology, and Traditional Ecological

Knowledges can tell us about human-environment interactions in the past.

She is a co-host of the podcast Warm Regards and author of the blog “The Contemplative

Mammoth”, welcoming conversations and advice on science, early career academia, and

diversity in STEM. She is a co-founder of the March for Science and a 2020 recipient of NCSE’s

Friend of the Planet award.

JACQUELYN GILL

BOTANY 2023

PLENARY SPEAKER

SUNDAY, JULY 23 7:30 PM

BOISE CENTER, BOISE, ID

Register now - www.botanyconference.org

PSB 69 (2) 2023

89

KAROLINA HEYDUK

BSA EMERGING LEADER

DON MANSFIELD

REGIONAL BOTANY LECTURE

JUN WEN

ASPT INCOMING PRESIDENT

ERIKA EDWARDS

KAPLAN MEMORIAL LECTURE

BRENDA MOLANO-FLORES

BSA INCOMING PRESIDENT

JILL WHITE

ANNALS OF BOTANY LECTURE

Botany 2023 Featured Speakers!

SEE the BOTANY 2023 WEBSITE for MORE INFORMATION

THESE TALKS WILL BE PRESENTED LIVE DURING the CONFERENCE

and RECORDED for the VIRTUAL PLATFORM.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

90

© 2022 LI-COR, Inc.

The LI-6800 Portable Photosynthesis System helps reveal it.

• Aquatic measurements—CO₂

gas exchange from algae and

other aquatic samples.

• Multiphase Flash™

Fluorometer—flash intensity of

up to 16,000 µmol m

-2

s

-1

.

• Dynamic Assimilation™

Technique—faster CO₂

response curves.

You share your research stories in

scientific journals, and the LI-6800

is designed to safeguard the

collection and quality of

publishable data. Automated

adjustments of experimental

parameters combined with stable

control of non-experimental

parameters empower you to test

hypotheses with high confidence.

The LI-6800 is the global standard

for photosynthetic gas exchange

and chlorophyll a fluorescence

measurements.

Your research has a story to tell.

The LI-6800 features novel

advancements not found in any

other photosynthesis system:

Learn more at

licor.com/6800

LI-COR and Multiphase Flash are registered trademarks of LI-COR, Inc. in the United States and other countries.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

91

PSB 69 (2) 2023

92

92

INTRODUCTION

Plant Study has been an integral part of the

college curriculum in the U.S. since before

the founding of the nation. In colonial times,

botany was studied primarily as a necessary

component of medical education and the

earliest botanists were physicians. By the

founding of the republic, however, botany

found its place in the field of natural history

at a growing number of institutions and the

teaching of botany was one of the leading

developments in what would become the

standard scientific curriculum. By the 1850s,

botany was one of the premier disciplines

represented in the American Association

155 Years of Botany at Emporia

State University: A Case Study of

College Botany in the United States

By Marshall D. Sundberg

Roe R Cross Distinguished Professor of Biology –

Emeritus, Emporia State University,

Emporia, KS

Email: msundber@emporia.edu

for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Already in 1875 Huxley and Martin had

published their elementary biology textbook

and with the founding of Johns Hopkins

University, academic biology became closely

connected with medicine. In 1882 the Natural

History Section of the AAAS split into four

subdivisions, including biology, but botanists

argued, “Upon even a casual examination

these courses, in almost every case, turn out

not to be courses in biology at all, but courses

in Zoölogy masquerading under an attractive

but deceptive name.” (Macmillan, 1893) This

argument was pivotal in establishing the

Botanical Society of America (Sundberg, 2014).

Nevertheless, by the 1920s biology overtook

botany in the high school curriculum. At the

college level, a 1931 survey of 202 U.S. colleges

and universities demonstrated that botany

remained the most taught introductory course

(59%) while zoology (51%) and biology (42%)

trailed (Schaefer, 1932); by 1937, biology had

replaced botany and zoology in the general

education requirements of more than 60%

of colleges. To address this problem, the BSA

Education Committee obtained NSF funding

for a series of summer institutes (1956-1969)

for small college, and some high school,

SPECIAL FEATURE

PSB 69 (2) 2023

93

teachers to update concepts in modern botany.

Yet, by 1969 it was also clear that botany

departments were being merged into biology

departments and in biology departments,

botany courses were being deleted (Stern).

This trend, documented in a series of Plant

Science Bulletin articles, continues into the

2020s (Sundberg, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2016;

Jones, 2020). For the past 125 years, botany

in the curriculum of today’s Emporia State

University, has followed a remarkable similar

trajectory.

CREATING A SOLID

FOUNDATION

The State of Kansas was admitted to the

Union in 1861, and in 1863 three institutions

of higher education were established: The

State Agricultural College in Manhattan, the

State Normal School in Emporia, and the

State University in Lawrence. This order of

legislation is an indicator of the legislators’

(many of them rural farmers) attitudes toward

education. The Ag School will be critical to

developing the state’s (and their) economies,

and the Normal school will provide teachers

to the schools being opened in many rural

communities. Then comes the university.

The Normal School was finally opened after

the Civil War ended in 1865, and Lyman

Kellogg was appointed as principal. The

following year Dr. Henry B. Norton, who

trained as a science teacher at the Illinois

State Normal School, was hired to teach the

natural sciences, including botany. The first

classes were taught on the second floor of the

Emporia Public School, and the college had

no equipment, books, or maps of their own.

The following year, the first college building

was completed and the 1868 catalog listed

anatomy and physiology, botany, and zoology

as the available natural science classes. In 1874

Norton left to accept a position at San Jose

Normal School in California and S. C. Delap,

Graduate of Millersville State Normal School,

PA, was hired as a replacement. Unfortunately,

the Normal School burned in 1878 and all the

equipment and school records were lost. With

the facility completely destroyed, the faculty

resigned en masse (anonymous, 1889; Prentis,

1899).

A new building was completed in 1880 (Figure

1), and Holmes Sadler was hired as the school

librarian and Natural Science and Elocution

instructor. The natural history classroom

and laboratory were in the basement; on the

first floor was a natural history museum and

recitation room. It is unclear if Sadler had

input into the design of the building, but he was

clearly in the vanguard of science education

theory. As Charles E. Bessey wrote in 1877,

“A college which proposes to keep up with the

current must provide botanical and zoological

laboratories ... A botanical laboratory is just as

necessary for the proper teaching of botany, as

is a chemical laboratory for chemistry” (Bessey,

1877). The 1880-81 catalogue states, “This

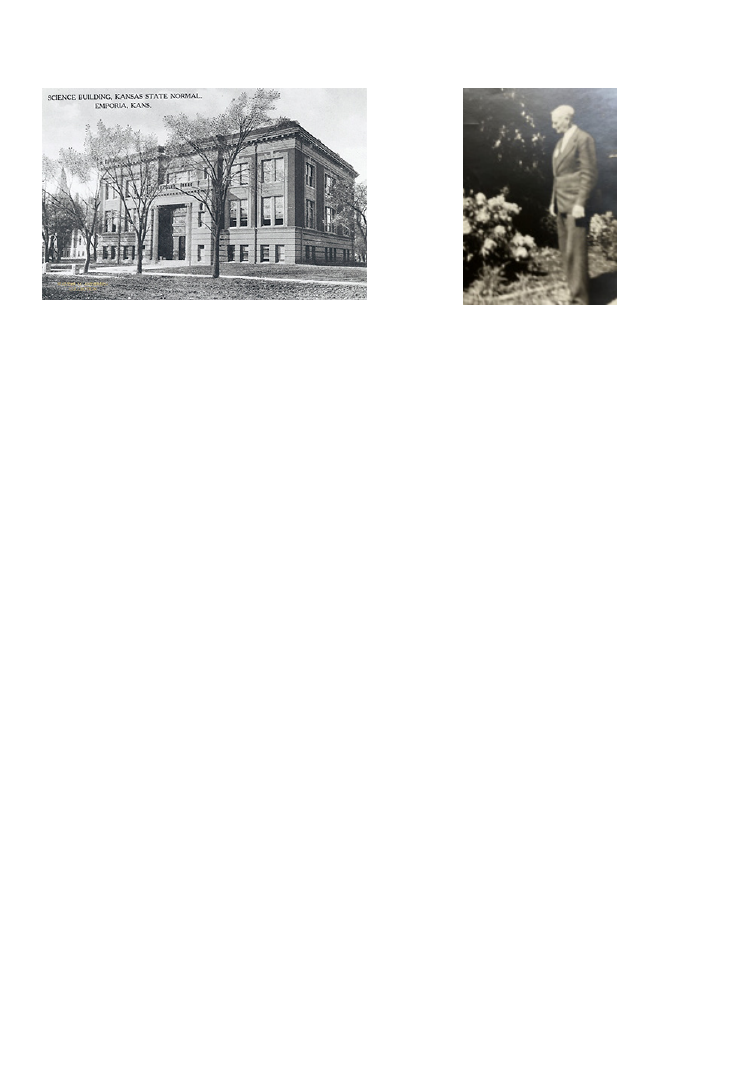

Figure 1. Kansas State Normal School,

1880. Botany was taught in the basement,

on the far west (left) side of the building.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

94

subject [botany] is taught more thoroughly

than any other branch of natural science,

from the fact that the methods of scientific

research do not materially differ in the various

branches, and the materials for extensive

and exhaustive research on this subject are

more readily accessible to our students”

(Catalog, 1880, p. 35). Indeed, both geology

and zoology were scheduled for one 10-week

term whereas botany consisted of 20 weeks of

study and included field and laboratory work.

In the 1881-82 through 1883-84 catalogs,

Sadler provides course descriptions. Students

should be able to describe the similarities and

differences between 40 genera, along with the

distinguishing characters of each, and describe

general principles of classification. They

would also consider the evolution (history)

and physiology of plants. The 1884-85 catalog

specifies Kellerman’s Elements of Botany as

the textbook (1883). This newly published

book was reviewed in Science as being “a

little bit more comprehensive…than books of

this grade usually are…unsatisfactory in its

execution in many respects, it comes nearer to

filling a serious gap in botanical literature than

any other thus far published…” (Science, 1884).

It is unknown what texts were originally used,

but the University library did subscribe to

Science so it is possible this review influenced

Sadler’s choice. However, Kellerman, the

author, was the new Professor of Botany at

Kansas State Agricultural College, so this

also may have influenced Sadler’s textbook

adoption.

It is interesting that for the first time,

components of the laboratory course are

individually specified in the Catalog. Students

were responsible for making a herbarium of

50 species with full descriptions. Each student

also had a compound microscope and was

responsible for making microscopic drawings

of cells and tissues of fungi, algae, and a variety

of land plants. Thus, the Normal School

in Emporia should have been included in

Arthur and Bessey’s lists of colleges adopting

“The New Botany” and requiring use of the

compound microscope in the laboratory

(Sundberg, 2012). In lab, students would also

do experiments with artificial soils (Catalog,

1884-85, p. 37).

In 1885 the regents organized a Department

of Natural History, and Dorman Kelly was

hired as Professor of Natural History to

replace Sadler, who left education and moved

to Memphis. Catalog course descriptions in

1885 were the same as the previous year except

the textbook would be Gray’s School and Field

Book of Botany (1880). The following year,

Kelly devised a new format for the course. At

the beginning of the term, the class would be

divided into two sections. The top half of the

students, in the first section, would receive

more rapid, compressed instruction for the

first 10 weeks. If they received a score of at

least 80%, they would pass the course and be

able to move on to another course. If not, they

would join the second section for the second

10 weeks of normal instruction. Except for a

change in textbook in 1887, Gray’s Lessons and

Manual of Botany, the structure of the course

remained the same for a decade until Kelly

was replaced by Lyman Wooster in 1897.

Wooster was primarily a geologist; as a result,

few changes were made in the botany offering.

The previous year, Bergen (1896) published

Elements of Botany, a somewhat briefer

book than Gray, which Wooster adopted to

complement Gray’s Field, Forest and Garden

Botany (1895) in the Botany course. Some

of the features that may have influenced

Wooster in adopting Bergen were end of

chapter summaries and, for some chapters,

PSB 69 (2) 2023

95

review questions to guide student study. Most

of Wooster’s students were future teachers, so

this provided practice. In 1902 he hired one

of his graduates, Elizabeth Crary, to assist

in teaching the natural history laboratory

courses.

In anticipation of a request to upgrade

the status of the school, the faculty of the

science departments—Biology and Geology,

Chemistry and Physics, Political Geography

and Physiography—compiled a booklet

detailing the course offerings and organization

of each department. It also included sections

on the Methods of Study. Botany continued

to be a 20-week course. During the first

section, which focused on morphology and

taxonomy, students were required to make

80 to 90 “judgements” (detailed descriptions

of characters) for each of 40 to 50 plants. But

first the student must make accurate labelled

drawings of the “plant for the day.” The

judgements for a given day must be prepared

ahead of time as the class time was spent

“verifying” the judgements (compare today’s

flipped classroom approach). “The knowledge

of the plants thus obtained by observation,

by the expression of judgements and by the

criticism of these judgements is still further

tested and corrected by requiring pupils

during the class hour to affirm or deny the

truthfulness of the statements made in several

keys…in so far as they apply to the plants at

hand” (Anonymous, 1904). In the laboratory,

morphological details were sketched and

labelled using water mounts and compound

microscopes. During the second section the

focus is on performing the 40 experiments

described in Bergen (1901) and “from the

personal experience of class members and

class reference books.” Plant anatomy involved

hand sectioning and observations with

the compound microscope, supplemented

with enlarged photographs of tissues, and

correlating structure with function. An

even richer understanding was obtained by

considering the ecology of the plants under

examination.

Beyond these specifics, the booklet went on

to explain some additional objectives of the

curriculum. First, the primary objective is

not to make “finished botanists” but rather

“growing botanists.” The second objective is to

develop students’ observational skills. Third is

to develop students’ power of forming valid

conclusions about what they have seen, felt,

or heard. “Most students in secondary schools

and colleges are weak in the ability to form

judgements about what their senses report, for

most school studies give them small occasion

to use their powers in this direction.” A final

objective is for students to acquire such a

knowledge of plants and love of botany that

they may successfully teach botany in the

elementary and secondary schools of the state

(Anonymous, 1904; Catalog 1905, p. 231).

In 1905 the school was authorized both to offer

bachelor’s degrees and to begin construction

of a new science building. The Department of

Natural Sciences now became the Department

of Biology and Geology, following a national

trend of combining botany and geology.

Biology programs first began to be offered

in U.S. colleges in the late 1880s as an

alternative to separate botany and zoology

programs. By 1911 about 30% of colleges

had biology departments (Sundberg, 2012,

2014). Emporia’s approach was a compromise.

General Biology was added as a 4-credit (cr.)

prerequisite for incoming students who had

not had a full year of high school botany or

zoology. The course taught the common

basic concepts required for both the botany

and zoology programs. A full curriculum of

PSB 69 (2) 2023

96

science courses was now required, and Crary

was promoted to instructor with primary

responsibility for the botany program. Norton

Science Hall was dedicated in November

1907 (Figure 2). A botany laboratory and two

classrooms were on the west end of the first

floor, and another laboratory and the Natural

History Museum were on the west end of the

second floor.

The following year, the curriculum was

expanded and another former student, Alban

Stewart, was hired as an additional instructor.

After one year Stewart decided to move on for

an advanced degree, and Frank U.G. Agrelius

was hired in 1911 to teach Bacteriology as

well as Botany (Figure 3). By this time Crary

had also completed some graduate work at

the University of Chicago and was promoted

to Professor. The botany curriculum now

consisted of 12 courses under the credit hour

system. Freshman Botany remained 4 cr.,

Advanced Field Botany was a 3 cr. summer

course, and the remaining courses were

single-semester, 2 cr. courses: Algae, Fungi,

Mosses and Ferns; Plant Physiology; Plant

Anatomy; History of Botany (summer only);

Economic Botany; Botanical Microtechnique

(summer only); and Nature Study. In 1913 the

Algae and Fungi courses were combined into

a single course and a new Botany in the High

School was added. Lab fees were also added

for some courses: Freshman Botany ($1.25),

Plant Physiology ($3.00), Plant Anatomy

($2.00), and Plant Microtechnique ($2.50)

(Catalog 1913).

According to the 1913-14 catalogue, a B.A. in

biology required 11 cr. in Bacteriology, 11 cr.

in Botany, 8 cr. in Zoology, 2 cr. of Plant Nature

Study, and 2 cr. of Evolution of Plant and

Animal Form; however, the botany offerings

were much reduced after Crary left in 1914.

For the next three decades Frank Agrelius

was the botanist (and bacteriologist) in the

department and the only regularly scheduled

botany courses were: Freshman Botany, Plant

Anatomy, Plant Physiology, Nature Study,

and Systematic Botany—each offered once

a year and occasionally also in summer. In

1916 the Freshman Botany was divided into

two separate courses, the first focusing on

development of spore plants and the second

on development of seed plants.

Figure 2. Norton Science Hall. Botany lec-

ture rooms and laboratories, 2

nd

and 3

rd

floors,

are on the west (left) side of building.

Figure 3. Frank Agrelius, who taught plant

taxonomy for 45 years.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

97

In 1923 the Normal School became

Kansas State Teachers College in Emporia.

Although there were some major changes

to the biology department, losing several

zoology and microbiology courses to newly

formed Department of Agriculture and

Health Education, botany was unscathed.

Agrelius, who had now completed a master’s,

was promoted to Associate Professor. In

1929 the department hired a new head,

John Breukelman, who initially focused

on advanced courses as the regents now

authorized master’s degrees for the college.

In 1930, 2-4 cr. of research was added to

each of the sub disciplines, including botany.

The following year three graduate-level

courses were added: Forest Botany, Special

Morphology of Algae, and Special Morphology

of Fungi. Breukelman’s reorganization of the

department was completed in 1935 when

the Department of Agriculture was merged

with the Department of Biology and Geology

to become the Department of Biological

Sciences. With Wooster now retired, geology

was split out to join with chemistry and

physics in a Department of Physical Sciences.

Breukelman, a charter member of the

National Association of Biology Teachers,

also instituted a Bachelor of Arts in Education

degree for prospective secondary teachers and

a biology minor for the master’s program.

There were no further significant botanical

changes to the department until after the war

(Catalogs, 1931-1935; Breukelman, 1963).

In 1946 the department was approved to

offer a graduate major in biology, and Merle

Brooks received the initial graduate teaching

fellowship. He completed his master’s the

following year and was immediately hired as an

instructor in biology while spending summers

at the University of Colorado pursuing a

doctorate in botany. Initially he taught only the

introductory botany and secondary education

courses, although when Agrelius retired in

1950, Brooks picked up the rest of the botany

courses, except plant systematics, which

Agrelius continued to teach until 1956 when

Brooks completed his doctorate (Breukelman,

1950, p. 190; Menhusen, 1959, p. 27).

Homer A. Stephens, an instructor–extension

agent hired part-time between 1951 and

1955, partially filled the systematics void, but

the Agrelius position was not replaced until

1955 when Gilbert Leisman, a paleobotanist

from Minnesota, was hired (Figure 4). He

changed Systematic Botany into a modern

plant taxonomy course and added Plants of

Kansas. But several courses were also deleted,

including Forest Botany, Spore Plants, Seed

Plants, and Elementary Biological Science.

In 1957 Joseph D. Novak, also with a botany

Ph.D. from Minnesota, arrived to teach

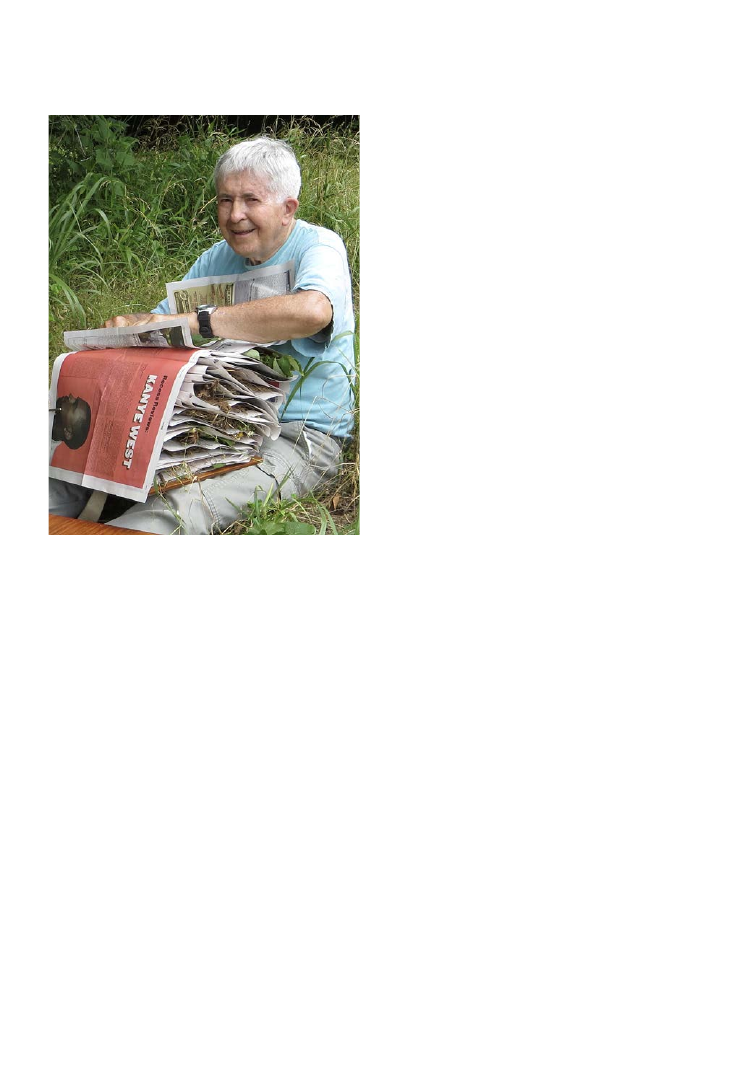

Figure 4. Gilbert Leisman in his Norton Sci-

ence Hall office. Leisman was a long-time

member of the BSA and served as chairman of

the Paleobotanical Section in 1967. He was

awarded several NSF grants to study Kansas

Coal Balls, Permian shale outcroppings at the

Ross Natural History Area, and the late Car-

boniferous Hamilton Quarry Lagerstätte.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

98

Introductory Botany and Science Education,

but left after only one year for a position at

Purdue University and ultimately at Cornell

University. The following year Brooks also

left, leaving Leisman the only botanist

in the department, along with Clarence

Glandfelter, who was hired in 1930 by the

Agriculture Department to teach agriculture

and conservation courses, but since the

department merger brought over Forestry and

Horticulture to biological sciences (Catalogs,

1951-1955, 1957; Bruekelman, 1963).

THE GOLDEN ERA

The entire country experienced a boom in

higher education following World War II,

with returning soldiers given incentives to

pursue education through the G.I. Bill. It is

interesting that before 1890, most high school

graduates went on to college, but this was

less than 4% of 18- to 21-year-olds (Hurd,

1961; Rudolph, 1977). After WWII, with the

dramatic rise in births and the realization

that upward mobility in the lower and middle

classes depended more and more on a college

degree, citizens and legislators put a priority

on expanding access to higher education.

Ironically, even with this general push toward

a college degree, “Scientific illiteracy became a

characteristic of college-educated Americans

some time toward the middle of the twentieth

century if not before” (Rudolph, 1977, p. 255).

Science, then, was a special case that required

additional culturing.

In my experience, as a low-level administrator

at two institutions, three things determine

the success you will have in reaching higher

goals for the unit: support from the top, a

person or core of people on the cutting edge

of innovation, and money–external grant

support. The Department of Biology in the

late 1950s and 1960s was fortunate to have

all three of these components come together

at the same time general support for higher

education was rising. In 1953 the College

inaugurated a new President, John E. King,

who was a strong supporter of the liberal

arts and sciences and in full agreement with

Bruekelman’s philosophy: “To prepare good

teachers you’ve got to first prepare them

intellectually” (Prophet, 1998). A new science

building for the physical sciences was begun

in 1956 and complete in 1959. Although

biology remained in Norton Science Hall, it

expanded to fill the building (Figure 5). In

1963, Brighton Lecture Hall was added to the

science building, and a new biology wing (now

Bruekelman Hall) was begun in 1966 (the last

year of King’s tenure) and completed in 1970.

In addition to these improvements in physical

infrastructure on campus, in 1958 the College

received an option to lease 1040 acres of prairie

on the edge of the Flint Hills, 14 miles west of

Emporia, for a natural history reservation to

be named after the benefactors, the late F.B.

Ross and Rena G. Ross. Breukelman, a field

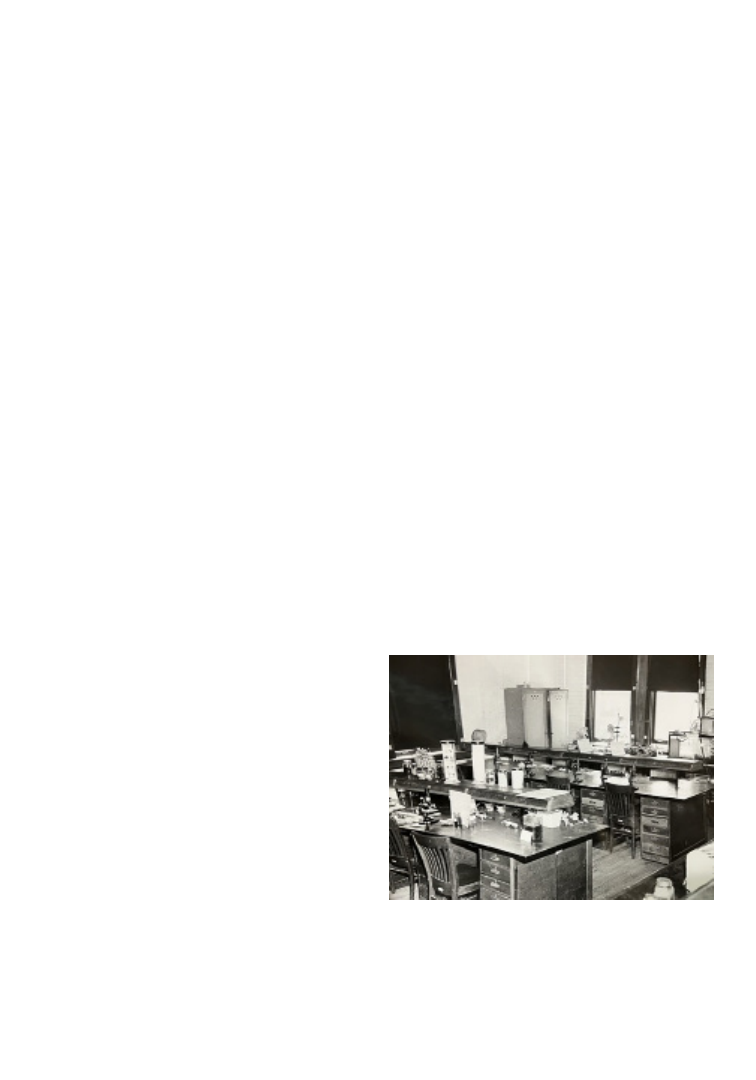

Figure 5. Original Botany Laboratory, 2

nd

floor, Norton Science Hall, now dedicated to

structural studies after plant physiology moved

into a wet laboratory vacated by Chemistry’s

move to the new Science building.

PSB 69 (2) 2023

99

biologist, was persuasive and the college took

the lease. Three years later the estate gifted the

southwestern 200 acres of the F.B. Ross and

Rena G. Ross Natural History Reservation

to the College, a gift accepted by the State

Board of Regents and Legislature. This facility

would turn out to be very important in the

department’s growth during the next decade.

In 1953 Bruekelman was well-aware of the state

of biology education in the country, having

recently completed 11 years as Editor of the

American Biology Teacher. The time was ripe

for change and post-war enrollment increases

were anticipated. In the fall of 1952, there were

5 faculty members serving 236 undergraduate

majors and 10 graduate students; ten years

later there would be 13 faculty serving more

than 705 undergrads and more than 60 grad

students. Graduate summer registration rose

from 15 to more than 100. In 1958 Breukelman

retired as chair, but he had been grooming his

replacement, Ted Andrews, for 10 years and

Andrews hit the ground running. Andrews

graduated from Emporia in 1940 and went on

for a master’s from Iowa, 3 years in the Naval

Reserve, and Ph.D. from Ohio State in 1948.

He immediately accepted a faculty position

in the biology department. Like Bruekelman,

Andrews was very active in NABT and both

served as President of the organization.

Major external grants at Emporia began

with the 1953-1959 Summer Conservation

Workshops, supported by the National Wildlife

Federation and led by Bruekelman. The Initial

NSF Summer Institute for Secondary Science

Teachers at Kansas State Teachers College

was received in 1957 and co-directed by

Merle Brooks, along with a physicist and a

mathematician. This program supported about

120 high school teachers, mostly from Kansas

and adjacent states, to complete two summer

courses in either biology, physical sciences, or

mathematics (about 40 in each). This grant

subsidized tuition and provided room and

board for the participant (and spouse and

family) and a small stipend. It was renewed

annually from 1957 to 1968. The grant also

supported a seminar series by distinguished

scientists who would come to campus for a few

days to a week during the session. Among the

botanists presenting over the duration of the

program were: Henry Andrews, Washington

University, Paleobotany; Leslie John Audus,

University of London, plant hormones;

George W. Beadle, Cal Tech, genes and

enzymes; John Dodd, Iowa State, Algology;

Harry J. Fuller, Illinois, economic botany;

Arthur Galston, Yale, photosynthesis and

plant metabolism; Richard Keeling, Purdue,

anatomy; Samuel Postlethwait, Purdue,

science education; Peter Raven, Stanford,

ecology, evolution; Paul Sears, Yale, plant

ecology; Bruce Stowe, Yale, plant physiology;

Ian Sussex, Yale, plant development; and

Billie Turner, Texas, systematics. Brooks also

coordinated the second year of the program

before leaving Emporia in 1959 for a position

at the University of Nebraska, Omaha.

Ted Andrews, who had just become head of

the department, took over leading the Summer

Institute while searching to replace Brooks

and add additional faculty positions to the

Department. Emily Hartman, with a Ph.D. in

plant taxonomy from Kansas, was hired from

California State Polytechnic College to replace

Brooks in 1958, taking over both his botany

and microbiology courses. However, in 1960

she returned to a position in California. For two

summers (1959 and 1960), Vincent Weber, a

plant anatomist from Minnesota, had a visiting

appointment specifically for the summer

institutes. Another short time hire, Gilbert

Hughes, replaced Weber in the summers of

PSB 69 (2) 2023

100

1961 and 1962, but also taught Microbiology

and Mycology during the academic year,

filling some of Brooks’ former role. A tenure-

track plant taxonomist, James Wilson was also

hired in 1959 specifically to replace Agrelius

and take over systematics. When Hughes left

in 1962, two new botanists were hired, Jack

Carter and Donald Ahshapanek. Carter was

an alumus (B.S. ’51, M.S. ’53) who went on

for a Ph.D. from Iowa. Although trained in

taxonomy, Carter was hired primarily to teach

the plant organismal courses and to take over

as Coordinator of the NSF Summer Institutes.

Like Andrews, Carter was already involved

in NABT, so he was a natural to take over the

grant programs. Ahshapanek, with a PhD in

Plant Physiology from Oklahoma, returned

to Kansas, where he did undergraduate work

at the Haskell Institute (now Haskell Indian

Nations University). The following year

Richard Keeling was hired specifically to teach

Microbiology and Mycology. Between 1960

and 1965 the number of biology faculty grew

from 13 to 23; botanists grew from three to

five (plus one part-time).

Realizing the potential for generating master’s

degrees, Andrews evolved the summer

institute program into a sequential institute so

that a student making satisfactory progress the

first summer could be supported to return the

following two summers. Under this format,

approximately 40 more biology majors could

be added to the graduate program for up to

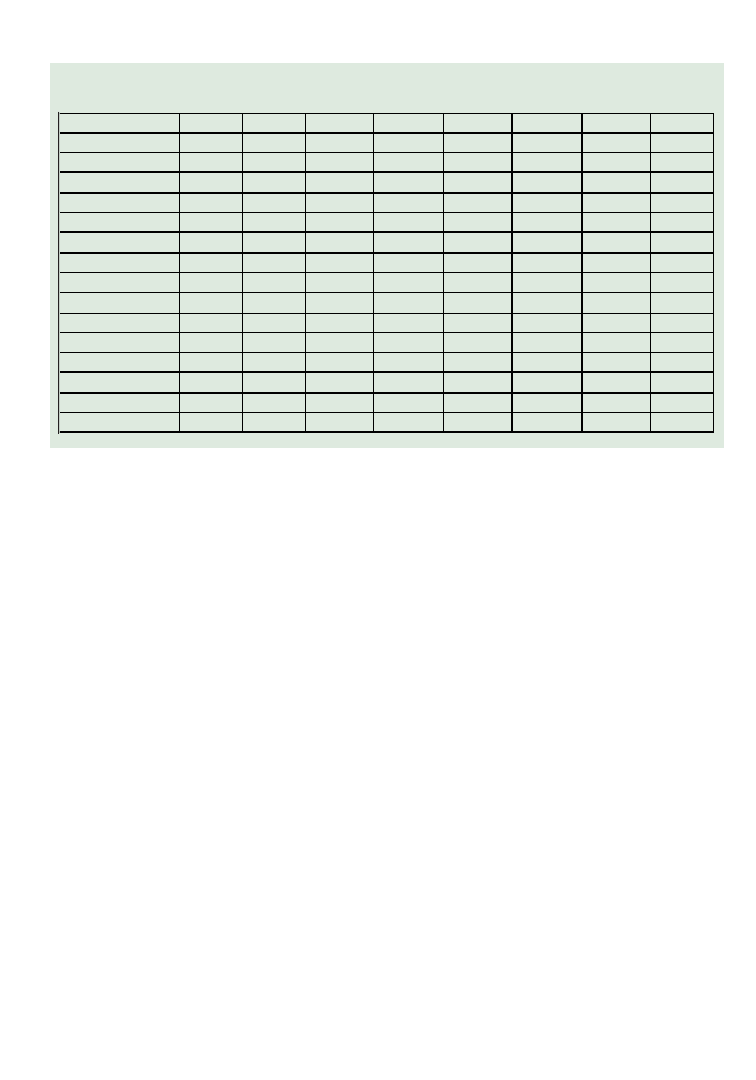

8 years (Table 1). Furthermore, a diversity of

upper level / graduate courses could be offered

on a regular basis, with fieldwork, class, and

research, based at the Ross Reservation (Table 2).

Andrews was also PI on two additional NSF

Grants. Research Participation for High

School Teachers in Biology at Kansas State

Teachers College ran from 1961 to 1968 and

selected 5-8 teachers to spend the summer

taking a research course under the direction

of one of the faculty members. Carter also

coordinated this grant during his tenure at

Emporia.

The Academic Year Institute for High School

Teachers in Biology at Kansas State Teachers

College, which ran from 1962 to 1964, was

also a team project with Andrews as P.I. and

Carter coordinating implementation of the

grant. Its purpose was to broaden teachers’

scientific knowledge and to improve their

ability to motivate their students to consider

STEM careers. The focus was specifically on

the subject matter rather than the methods

of teaching. Thirty teachers were chosen each

year to participate in a full load of graduate

courses and research with the option of partial

support the following summer to complete

the master’s. The program also included

optional spring break field trips. The first

involved caravanning through Tamaulipas,

San Luis Potosi, and Nuevo Leon, Mexico;

subsequent years involved backpacking trips

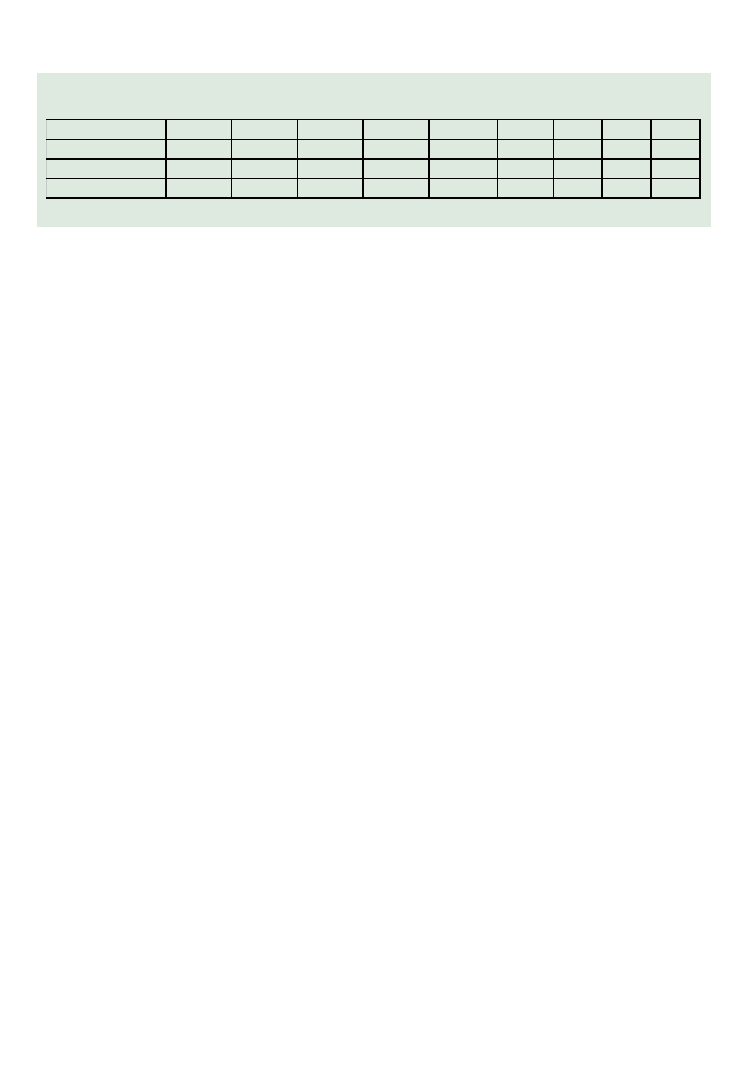

Table 1. Biology Participants in NSF Summer Institutes and Number of Master’s Graduates

Year

1957

1958

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963

1964

Participants

50

50

44

49

50

50

49

38

1

st

time

50

50

32

23

17

17

23

15

Returning

0

0

10

26

38

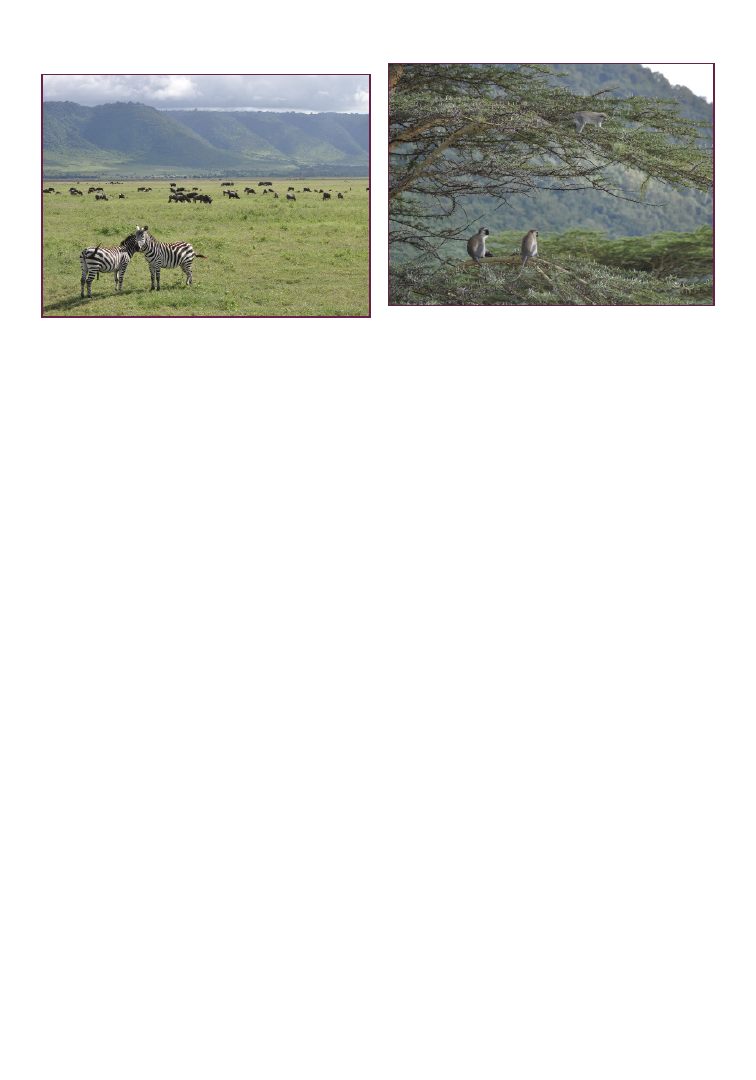

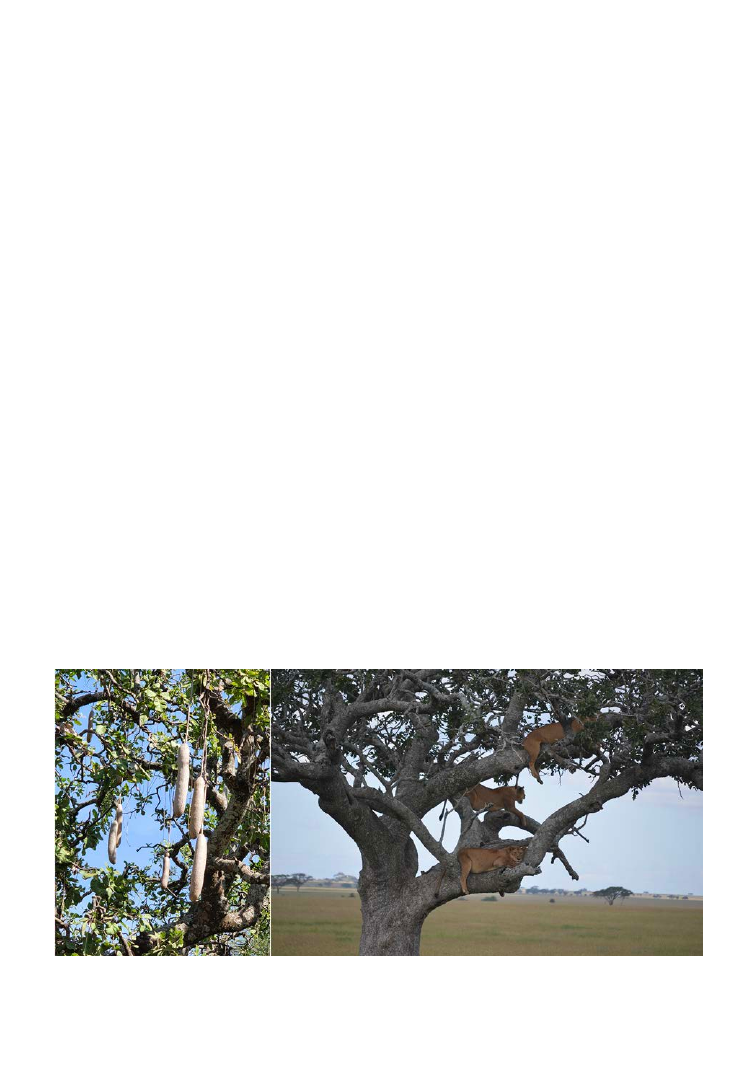

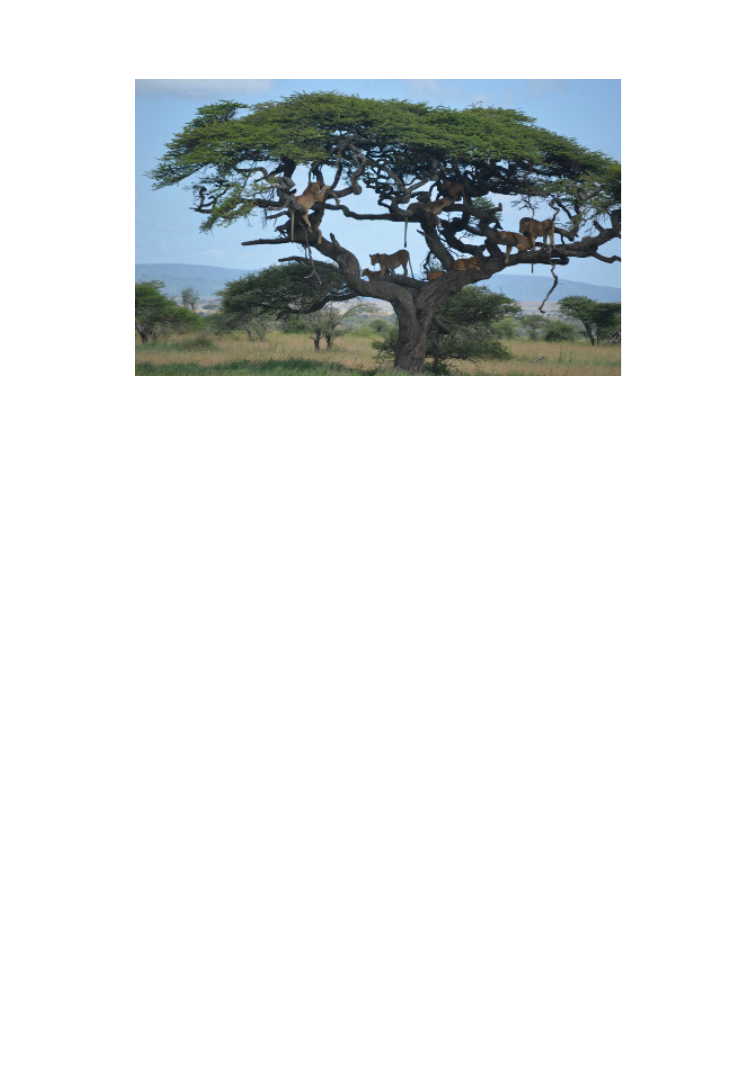

38