IN THIS ISSUE...

FALL 2019 VOLUME 65 NUMBER 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Meet new BSA Student Representative,

Shelly Gaynor.... p. 177

Students beta-testing new

PlantingScience module.... p. 174

Old trees meet new technology.... p. 156

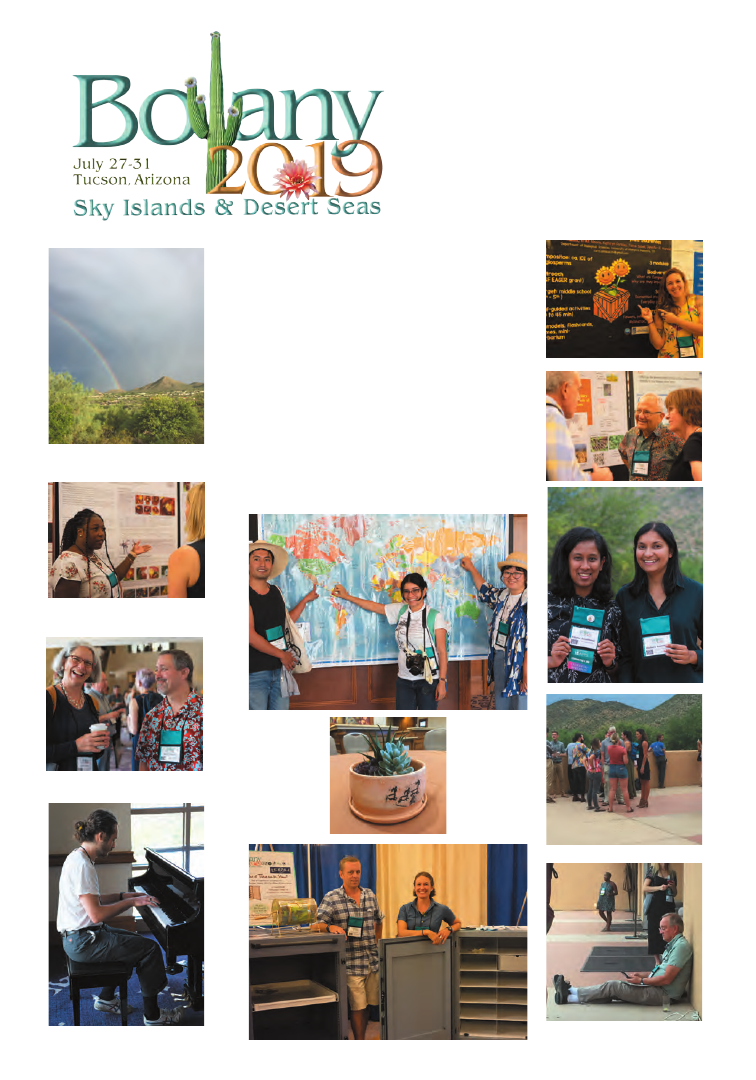

Botany 2019: A Fantastic Time in Tucson!

Fall 2019 Volume 65 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 65

From the Editor

Melanie Link-Perez

(2019)

Department of Botany

& Plant Pathology

Oregon State University

Corvallis, OR 97331

melanie.link-perez

@oregonstate.edu

Shannon Fehlberg

(2020)

Research and Conservation

Desert Botanical Garden

Phoenix, AZ 85008

sfehlberg@dbg.org

David Tank

(2021)

Department of Biological

Sciences

University of Idaho

Moscow, ID 83844

dtank@uidaho.edu

James McDaniel

(2022)

Botany Department

University of Wisconsin Madison

Madison, WI 53706

jlmcdaniel@wisc.edu

Greetings,

I hope that those of you who made the

trip to Tucson found this year’s Botany

meeting to be productive and stimulat-

ing. It was my first time in Arizona and

I particularly enjoyed the landscape.

As always, we are pleased to list the

winners of awards that were presented

during the meeting. Congratulations

to all!

I want to highlight a pair of articles in

this issue that address botanical ed-

ucation for general audiences—one

looking back at the work of influential

past botanists and the other focusing

on using modern social media tools to

engage the community. It is important

and inspiring to consider those who use

creative and contemporary resources

to promote plant and environmental

science. Many in our professional com-

munity are doing incredible outreach

with both local and global audiences.

At PSB, we are always pleased at high-

light those projects, either as articles or

as features in the Education News and

Notes section.

143

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOCIETY NEWS

Public Policy Committee Report Supporting Evidence-Based Policy

Through Public Comments ............................................................................................................................144

BSA Promotes Author Workshop at the XXI Congreso Mexicano de Botánica in

Aguascalientes, Mexico ...................................................................................................................................146

New

AJB Reviews

Feature Coming In 2020 ............................................................................................147

BSA Members Participate in 2019 Climate Strike ...............................................................................147

Botanical Society of America’s Award Winners

(Part 2)

...................................................................148

Botany 2019 - It's More Than Just Another Scientific Conference! ..........................................153

SPECIAL FEATURES

Old Trees Meet New Technology ...................................................................................................................156

Inspirational Voices in Early Botanical Education .................................................................................161

SCIENCE EDUCATION

“Botanists: See Zoologists and Wildlife Biologists”: Seeking Resources on

Careers for Plant People ................................................................................................................................172

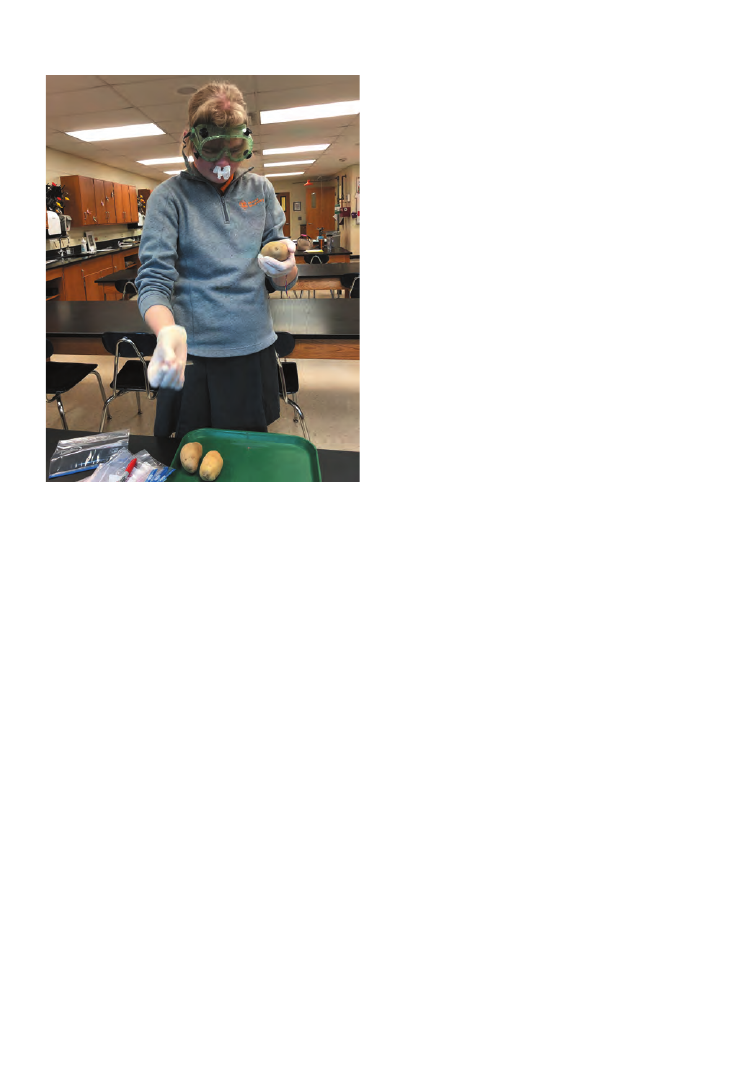

PlantingScience Launches new “Plants Get Sick, Too!” Theme in Collaboration

with American Phytopathological Society .............................................................................................174

Thanks to PlantingScience’s Early-Career Scientist Support Team .........................................175

STUDENT SECTION

Getting to Know Your New Student Representative: Shelly Gaynor ...........................................177

Quick Notes on the Botany 2019 Conference .......................................................................................179

ANNOUNCEMENTS

New BSA Social Media Liaisons Selected for 2019-2020..............................................................180

Harvard University: Bullard Fellowships in Forest Research ...........................................................181

In Memoriam

Personal Reflections on a Guiding Light: Winslow R. Briggs (1928-2019) ........................182

Arthur Oliver Tucker, III (1945-2019) ........................................................................................................185

W. Mark Whitten (1954–2019) ....................................................................................................................188

BOOK REVIEWS

Biographies ..................................................................................................................................................................192

Ecology ..........................................................................................................................................................................195

Economic Botany .....................................................................................................................................................196

Physiology ....................................................................................................................................................................197

Systematics.................................................................................................................................................................199

144

SOCIETY NEWS

Public Policy Committee Report

Supporting Evidence-Based Policy

Through Public Comments

By BSA PPC Co-Chairs Krissa Skogen (Chicago Botanic

Garden) and Kal Tuominen (Metropolitan State University)

and ASPT PPC Chair Andrew Pais (North Carolina State

University)

During the past year, we have highlighted

ways that BSA members can support science-

friendly candidates and legislation to increase

the capacity for botanical expertise in the

federal workforce (PSB 65[1]: 2019). Winners

of this year’s (BSA) Public Policy Awards,

(ASPT) Congressional Visits Day Award and

(BSA/ASPT) Botany Advocacy Leadership

Award have also described their experiences

reaching out to elected officials (PSB 65[2]:

2019). Another way our members have

engaged in public policy is by providing public

comments on proposed rules or rule changes.

Public comments can be a highly effective

way of leveraging your subject matter

expertise to create positive change. However,

many scientists are unaware of what a public

comment is or how governments use them.

While new laws are introduced by parts of the

legislative branch (e.g., the federal House of

Representatives), proposed rules are created

by parts of the executive branch (e.g., the

Environmental Protection Agency) in order to

carry out existing laws (e.g., the Endangered

Species Act). Because civil servants with

technical expertise are often involved in

proposing and altering rules, public comments

can be surprisingly similar to writing or orally

presenting research findings to a scientific

audience. Here we provide some tips for how

to get started with your first public comment.

IDENTIFYING YOUR

SUBJECT MATTER

EXPERTISE

Within the scientific

community, we often assume

that our subject matter

expertise begins and ends

with our own research. In

the context of public policy,

however, that expertise is

far broader. What graduate-

level STEM courses have you

completed or do you teach?

What topics did your graduate

committee expect you to

PSB 65 (3) 2019

145

discuss during comprehensive exams? Have

you been a co-author on any side projects?

Have you used your scientific training to

help a nonprofit organization become more

effective? How do you explain the relevance

of your work to friends and neighbors? The

answers to these questions can help you

identify what your subject matter expertise

looks like to elected officials. It is likely that

you have expertise in many subjects, or that

you have not fully constructed the nature of

your expertise in the context of a particular

policy issue that interests you!

IDENTIFYING PROPOSED

RULES OR RULE CHANGES

While many scientists become aware of pro-

posed rules or changes directly through their

own research, by law most governments in the

United States must publicly announce such

proposals. The federal government makes

these announcements in the Federal Regis-

ter (www.federalregister.gov), and StateScape

provides links to state registers (http://www.

statescape.com/resources/regulatory/regis-

ters/). If you are interested in science policy

but unsure about how to leverage your sci-

entific knowledge, try searching one of these

registers to identify opportunities to comment

based on your location, subject matter exper-

tise, agency, and comment deadline.

WRITE AND SPEAK

While federal public comments are typically

submitted in writing, state and local

governments often hold community hearings

to take verbal testimony in addition to a venue

for submitting written comments. Attending

a community hearing is an excellent way to

become familiar with the rule-making process

and to learn deeply in a short amount of

time about multiple viewpoints on the issue.

Any verbal testimony you provide will be

documented and made public, so prepare as

you would for a conference presentation or

course lecture. The number and geographic

locations of hearings tends to be limited,

so if you are unable to travel on a specific

day, providing a written comment is still

a good option. In our experience, written

comment periods typically last 60 to 90

days; your state or local government may

have different expectations. If you need

assistance writing your first public comment,

the Public Comment Project provides more

detailed guidelines and templates (https://

publiccommentproject.org/how-to).

KNOW YOUR RIGHTS

Scientists speaking publicly on politically

challenging topics such as climate change

experience political and sometimes legal

opposition. Depending on your professional

role, the sort of information you may legally

provide in a public comment may also be

limited. OrgÍanizations such as the American

Institute of Biological Sciences (www.aibs.

org), the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund

(csldf.org), and the government affairs office

at your institution can help you navigate

the less familiar aspects of using your First

Amendment rights and your professional

expertise for the betterment of society.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

146

In support of the Society’s commitment to

greater international collaboration, the BSA

publications group and Wiley, our publishing

partner, hosted a free author workshop at

the XXI Congreso Mexicano de Botánica on

October 23, 2019, in Aguascalientes, Mexico.

Like the workshop held at the XII Congreso

Latinoamericano de Botánica in Quito,

Ecuador (2018), this workshop focused on what

researchers can do to improve their chances

of getting published in a scientific journal—

and then what they can do after their paper is

published to make sure it is discovered by the

larger community. Topics covered included:

Choosing a journal, writing the paper clearly

and concisely, and convincing the editor it

should go out for review; understanding what

happens during peer review and revision;

making your paper “discoverable” to search

engines and promoting your own work

through various channels; learning about

ethical issues in publishing; and getting advice

for publishing in foreign language (primarily

English) journals.

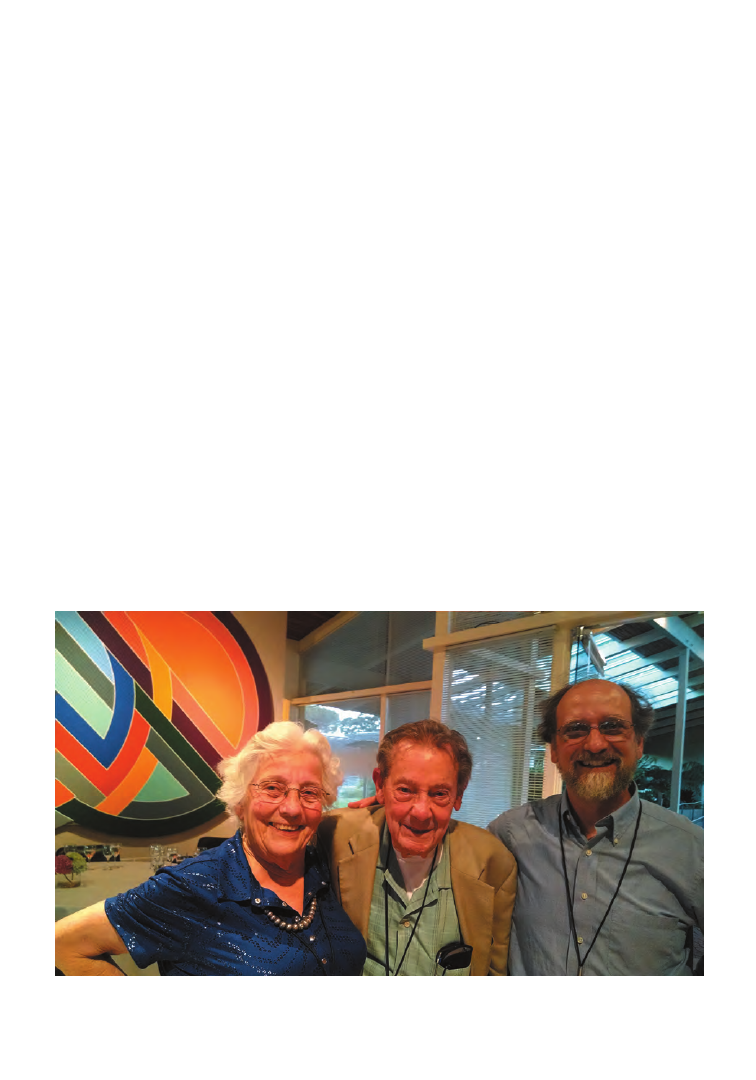

The presenters at the workshop were Amy

McPherson, BSA Director of Publications

and AJB managing editor; Gillian Greenough,

Executive Editor, Life and Physical Sciences,

Research & Society Services at Wiley; and

Marcelo Rodrigo Pace, Investigador Asociado

at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de

México and Editor-in-Chief of the IAWA

Journal. The presentation was given mostly

in English, with slides translated into Spanish

as a handout for attendees. Pace provided

advice from his own publishing experience

and helped with the Q&A in Spanish. Heather

Cacanindin, Executive Director of the

Botanical Society of America, attended the

Congreso in support of botanical colleagues

in Mexico and provided information about

the benefits of joining BSA.

We look forward to continuing to expand

the BSA’s international outreach at upcoming

conferences.

BSA Presents Author Workshop at

the XXI Congreso Mexicano de

Bot

á

nica in Aguascalientes, Mexico

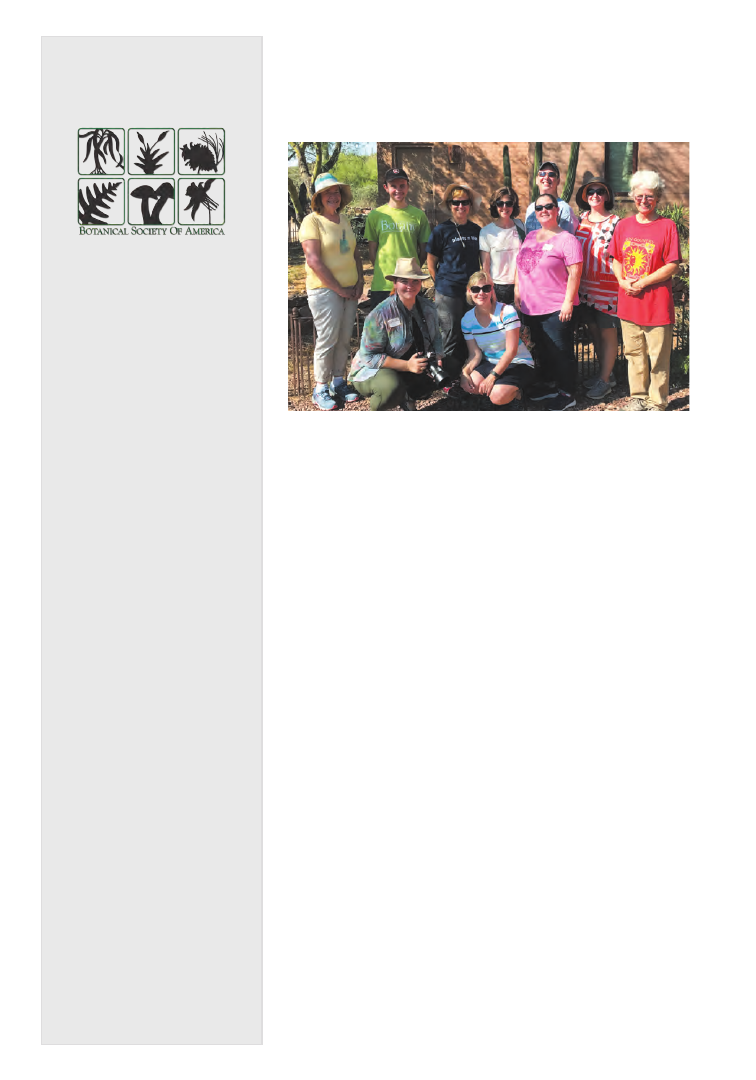

Marcelo Pace, AJB Managing Editor Amy McPherson, and Wiley Representative Gillian Gre-

enough [front row center] led the author workshop at XXI Congreso Mexicano de Botánica.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

147

BSA MEMBERS

PARTICIPATE IN

2019 CLIMATE STRIKE

The 2019 Climate Strike attracted BSA members

from around the globe. Here, Dr. David Ehret

participated in the Climate Strike in Victoria, BC,

Canada. “I thought it was important to add my

voice to the chorus of others demanding climate

action,” Ehret said. “I was most impressed by all

the millennials and Gen Z’ers at the protest. It was

so inspiring to see such passion and commitment

among the young.”

New

AJB Reviews

feature

coming in 2020

AJB Reviews is set to launch in 2020! These reviews will expand the coverage and reach of the

journal by providing timely syntheses of major issues, and new insights or perspectives to guide

future research.

AJB Reviews, headed by Drs. Jannice Friedman, Emily Sessa, and Pamela Diggle, place topics

in context while being forward-thinking and insightful. They can develop new hypotheses and

propose general models that help move the field forward. Original interdisciplinary syntheses

and articles that cover newly emerging fields are welcomed. Authors can express a personal

perspective while maintaining a balanced view of the field.

Anyone interested in submitting to AJB Reviews should provide a preliminary summary of

up to 250 words. A decision on whether to invite a full review rests with the Editorial Board.

All contributions will be fully peer-reviewed, in line with other AJB manuscripts. For more

information, go to https://bit.ly/2LvM1BE or e-mail the Reviews Editor at reviews@botany.org.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

148

The BSA was pleased to announce its annual

award winners in the last issue of the Plant

Science Bulletin. We now present the rest of

the awards available at press time.

CONGRATULATIONS TO

2019 BESSEY AWARD WINNER

SUZANNE KOPTUR!

This year the BSA recognized Dr. Suzanne

Koptur, Professor at Florida International

University, with the Charles Edwin Bessey

Teaching Award. This award recognizes

outstanding contributions made to botanical

instruction and celebrates individuals

whose work has improved the quality of

botanical education at a regional, national, or

international level. The Bessey Award is the

highest honor for Teaching and Educational

Outreach given by the Botanical Society of

America.

Suzanne has been an active member of the

BSA since graduate school. She has presented

over 40 papers at BSA conferences over the

years, both ecological and educational, and

is a member of the Teaching, Ecology, and

Tropical Biology sections.

Suzanne is a clear fit with the qualities

recognized by the Charles Edwin Bessey

Teaching Award. During her career she has

mentored an exceptional number of graduate

and undergraduate students, including

many from groups under-represented in the

sciences. She actively seeks funding to provide

early opportunities for her students, providing

opportunities for undergraduate researchers

to join her and her graduate students in the

lab and field, supporting and encouraging

them to attend and present at botanical

meetings, and to be involved in the PLANTS

mentoring program and other career-building

opportunities. In 2017 she was awarded the

FIU University Graduate Student Provost

Award for Mentorship of Graduate Students

recognizing her mentoring efforts. One of

her former students writes: “Through her

vocation to training the next generation of

botanists, she has left a lasting legacy. Every

one of us that has had the great fortune in

having Suzanne as a teacher will go forth as

emissaries for science, creating a ripple effect

that will spread her passion for plants far and

wide throughout the world.”

Botanical Society of America’s

Award Winners

(Part 2)

PSB 65 (3) 2019

149

Suzanne is an active and engaged teacher who

embraces new teaching techniques like active

learning, flipped courses, and online teaching.

She was active in creating a new FIU initiative,

Quantifying Biology in the Classroom (QBIC),

to help biology students develop quantitative

skills to help them succeed. She served as the

QBIC director from 2012-2016, and continues

to serve this program as co-director. She

contributes to the research on teaching and

has made great impact in developing and

supporting a culture of teaching innovation

within her department.

In addition to her work at FIU, she is active

in community outreach. She has been a

supporter and proponent of Fairchild Tropical

Botanic Garden’s Connect to Protect program

encouraging citizens and schools to help create

habitat corridors between the endangered

South Florida Pine Rocklands.

She has worked with local schools to

build butterfly gardens, organizes several

conferences that bring researchers and natural

resource management professionals together,

and serves on county committees to develop

conservation initiatives.

The Bessey Award is given annually in honor

of one of the great developers of botanical

education, Dr. Charles Edwin Bessey. Dr.

Bessey served first as professor of botany and

horticulture, and later as dean at the University

of Nebraska.

His work and dedication to

improving the educational aspects of Botany

are most noted in what Nebraskans call

“The Bessey Era” (1886-1915), during which

Nebraska developed an extraordinary program

in botany and ranked among the top five

schools in the United States for the number of its

undergraduates who became famous botanists.

Past Bessey award winners include: Lena

Struwe, J. Phil Gibson, Bruce K. Kirchoff,

Shona Ellis, Paul H. Williams, Les Hickock

and Thomas R. Warne, Susan Singer, Geoff

Burrows, Chris Martine, Roger Hangarter,

Beverly Brown, Michael Pollan, Thomas

Rost, James Wandersee, W. Hardy Eshbaugh,

David W. Lee, Donald Kaplan, Joseph

Novak, William Jensen, Joseph E. Armstrong,

Marshall D. Sundberg, Gordon Uno, Barbara

W. Saigo and Roy H. Saigo, and Samuel Noel

Postlethwait.

BSA CORRESPONDING MEMBERS AWARD

Corresponding members are distinguished senior scientists who have made outstanding

contributions to plant science and who live and work outside of the United States of America.

Corresponding members are nominated by the Council, which reviews recommendations and

credentials submitted by members, and elected by the membership at the annual BSA business

meeting. Corresponding members have all the privileges of lifetime members.

Dr. Richard Abbott, University of St Andrews, London, United Kingdom

Dr. Lucia Lohmann, Universidade de São Paulo (USP), Sao Paulo, Brazil

Dr. Jefferson Prado, Instituto de Botânica, Herbário, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Dr. Victor Rico-Gray, Universidad Veracruzana, Veracruz Mexico

Dr. Fernando Zuloaga, Instituto de Botánica Darwinion, San Isidro, Argentina

PSB 65 (3) 2019

150

DONALD R. KAPLAN MEMORIAL LECTURE

Dr. John Z. Kiss, University of North Carolina, Greensboro

John’s interest in space biology has led to past spaceflight projects which used microgravity as a

tool to understand the mechanisms of tropistic responses. Currently, his team has been approved

by NASA for several new experiments on the International Space Station to investigate plant

tropisms. His long-term goal is to understand how plants integrate sensory input from multiple

light and gravity perception systems.

MARGARET MENZEL AWARD

(GENETICS SECTION)

The Margaret Menzel Award is presented by the Genetics Section for the outstanding paper

presented in the contributed papers sessions of the annual meetings.

Erika Frangione, University of Toronto Mississauga, for her presentation: Comparative

transcriptomics of repeated reticulate evolution in the genus Cuscuta (Convolvulaceae). Co-

author: Saša Stefanović

EDGAR T. WHERRY AWARD

(PTERIDOLOGICAL SECTION AND

THE AMERICAN FERN SOCIETY)

The Edgar T. Wherry Award is given for the best paper presented during the contributed papers

session of the Pteridological Section. This award is in honor of Dr. Wherry’s many contributions to

the floristics and patterns of evolution in ferns.

Hannah Ranft, Johns Hopkins University, for the presentation: Sometimes it only takes one

to tango: using natural history collections to assess the impact of asexuality in the fern genus

Pteris. Co-authors: Kathryn Picard, Amanda Grusz, Michael Windham, Eric Schuettpelz

PSB 65 (3) 2019

151

THE BSA UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT

RESEARCH AWARDS

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards support undergraduate student research and

are made on the basis of research proposals and letters of recommendation.

Blake Fauskee, The University of Minnesota-Duluth, for the proposal: Could RNA editing

explain phylogenetic rate heterogeneity in seed-free vascular plants?

Brianna Reynolds, The University of Tennesse-Knoxville, for the proposal: Identifying Fungal

Endophytes in a Myrmecochore, Chelidonium majus

Susana Vega, University of Antioquia, Colombia, for the proposal: Taxonomic Revision of the

Genus Selaginella P. Beauv. (Selaginellaceae) in the Department of Antioquia, Columbia.

Paige Wiebe, Kansas State University, for the proposal: Niche divergence in big bluestem grass

ecotypes in response to experimental drought: Mechanisms of local adaptation

Noah Yawn, Auburn University, for the proposal: Reassessment of the Endangered Alabama

Canebrake Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia Alabamensis, Populations and Occurrences in Collaboration

with the Atlanta Botanical Garden

KATHERINE ESAU AWARD

(DEVELOPMENTAL AND STRUCTURAL SECTION)

This award was established in 1985 with a gift from Dr. Esau and is augmented by ongoing

contributions from Section members. It is given to the graduate student who presents the

outstanding paper in developmental and structural botany at the annual meeting.

Joyce Chery, University of California-Berkeley, for the presentation: Evolution of strange

wood development in a large group of neotropical lianas, Paullinia (Sapindaceae). Co-

authors: Marcelo Pace, Pedro Acevedo-Rodriguez, Carl Rothfels, Chelsea Specht

PSB 65 (3) 2019

152

PHYSIOLOGICAL SECTION LI-COR PRIZE

Lauren Tucker and Amanda Salvi tied for the LI-COR Prize for an Oral Paper

Laurent Tucker, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, for the presentation: Recovery

of California black walnut trees following drought induced dieback. Co-authors: Frank Ewers,

Stephen Davis, Edward Bobich

Amanda Salvi, University of Wisconsin - Madison, for the presentation: Mesophyll

photosynthetic sensitivity to leaf water potential increases in Eucalyptus species native to

moister Australian climates: a new dimension of plant adaptation to drought. Co-authors:

Duncan D. Smith, Kate McCulloh, Thomas Givnish

Steven Augustine and Katie Krogmeier for the LI-COR Prize for Best Poster

Steven Augustine, University of Wisconsin - Madison, for the poster: Going for broke: carbon

and water relations of germinant conifer seedlings exposed to drought. Co-author: Kate

McCulloh

Katie Krogmeier, Appalachian State University, for the poster: Investigating potential impacts

of polyploidy on the ecophysiological responses of Solidago altissma to climate change. Co-

authors: Howard Neufeld, Erica Pauer

PHYSIOLOGICAL SECTION STUDENT

PRESENTATION AWARD

Helen Holmlund, University of California, Santa Cruz, for the Best Oral Presentation: High-

resolution computed tomography reveals dynamics of desiccation and rehydration in a

desiccation-tolerant fern. Co-authors: Brandon Pratt, Anna Jacobsen, Stephen Davis, Jarmila

Pittermann

It's more than just

another scientific

conference!

This year 1200 people from all over the

world came together in Tucson, Arizona

as colleagues, collaborators, students, and

friends of Botany!

Friendships are formed, science is shared,

knowledge is expanded!

It's more than a scientific meeting - it's a

yearly reunion of people with the same

interests and passion for science - with a lot

of fun thrown in!

Botany 2019 Beverages by the Numbers

1121 Servings of Craft and Domestic Beer

1227 Glasses of Wine

923 Gallons of Coffee

49 Gallons of Fruited Water

PSB 65 (3) 2019

155

Botany 2019 in your words.....

• I attended the in-service at the Mission Garden. I loved the

experience, and am happy I had the opportunity to participate!

• Crop wild relative conservation field trip is very nice!

• Culture of botany conference is very pleasant and

inviting, contributes to enjoyable experiences speaking

with a wide range of botanically inclined folks.

• I enjoyed the conference, and it was really nice

to be able to go hiking right from the hotel.

• This was one of the best meetings ever. The energy was great.

Personally, I think it is because participants could get outside

easily, and because they could hike so readily. I went out for an

hour or more every morning but one. Those hikes left me high

for the rest of the day.

• It was a stunning setting, which made the stay very pleasant.

• I attended probably the best symposium since I began coming to

BSA...the Land Plant Evolution symposium was outstanding.

• Loved the venue, we should consider going back there in a

few years. You did a good job providing vegan food this time

(usually there are no options, or the options aren't very good).

The student housing rates were adequate enough to encourage

students to attend.

• I think the PLANTS program and travel grants are extremely

valuable. I have participated as a PLANTS mentor for 3 years,

and I plan to continue participating whenever possible.

• It was both scientifically stimulating and lots of fun

• I really enjoy the friendly atmosphere and the chance to see

cool talks and catch up with colleagues!

156

SPECIAL FEATURES

I

f my own childhood is any indication, many

a child has grown up wishing that trees

could talk. In fact, recent events suggest that

it is not just children, but adults too, who wish

this were so. In 2010, the European magazine

Eos launched “The EOS Talking Tree.” They

fitted an urban tree with various sensors

and used these to give the tree emotions and

opinions (Galle, 2016). The tree’s website

was visited over 350,000 times (Galle, 2016).

Shortly after, another public-tree event took

place in Australia (Lafrance, 2015). In 2013, a

government tree-servicing program, intended

to improve tree maintenance in the city of

Melbourne, took an odd turn. When given the

opportunity to use unique tree-codes to e-mail

the city and inform workers of maintenance

needs, citizens instead wrote thousands of

love letters to the city’s trees (Lafrance, 2015).

Then, in the summer of 2018, an agave plant

in the Halifax Public Gardens became a local

celebrity and took the city by storm (Berry,

2019).

These examples point to a human desire

to connect to, and communicate with,

nature. Though novel in Western thought,

communication across different species is

featured in many Indigenous oral traditions

(Legge and Robinson, 2017). Unfortunately,

research suggests that modern people

are more disconnected, both emotionally

and physically, from nature than previous

generations (Barlett, 2008; Vining et al.,

2008). With over 80% of Canada’s population

residing in urban areas (Statistics Canada,

2014), access to and engagement with urban

nature is important now more than ever.

Understanding public values and testing

engagement strategies is, then, vital to urban-

forest management (Ordoñez et al., 2017).

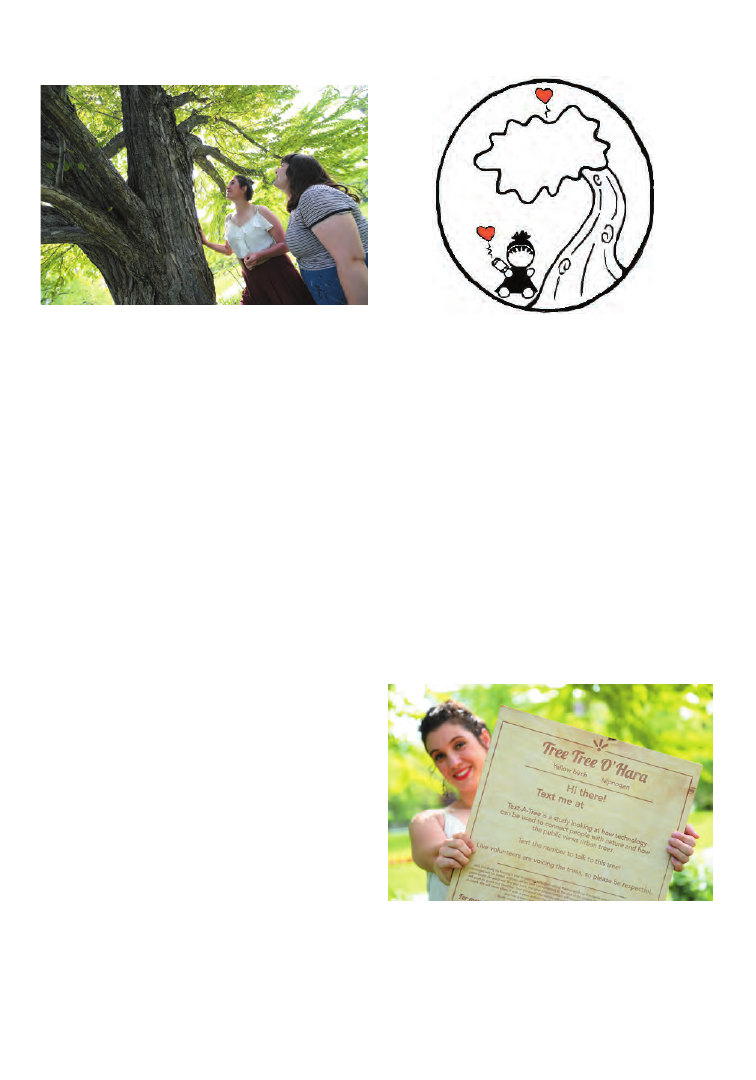

On July 7, 2019, a team of volunteers and

I launched Text-A-Tree: one part public

engagement and one part academic study

(Figs. 1, 2). Text-A-Tree serves as the final

project in my Master’s of Resource and

Environmental Management at Dalhousie

University, under the supervision of Dr. Peter

Duinker. An underlying theory behind the

initiative is that if we want to encourage people

Old Trees Meet New Technology

By Julietta Sorensen Kass

Dalhousie University

e-mail: jl883690@dal.ca

www.halifaxtreeproject.com/textatree

PSB 65 (3) 2019

157

to develop relationships with trees, we should

emulate the way we develop relationships

with each other. For many of us, that now

involves texting. So, from July 7 to August 31,

visitors to the Halifax Public Gardens can text

several trees and receive unique responses

within 24 hours. Participants can also engage

through our social media platforms using

@TextATreeHalifax.

Text-A-Tree hopes to determine whether

texting and social media can be used to

engage people with urban trees. The results of

the study will help inform future engagement

strategies relating to urban forests or urban

nature. As described by Ordóñez et al. (2017),

understanding public values relating to urban

forests can help guide and broaden effective

management. The project will determine the

utility of text-based engagement compared

with Instagram and Facebook engagement,

providing insight into communication

strategies. Analysis of text conversations will

add to the growing research on how Canadians

perceive and value urban forests (Ordóñez et

al., 2016).

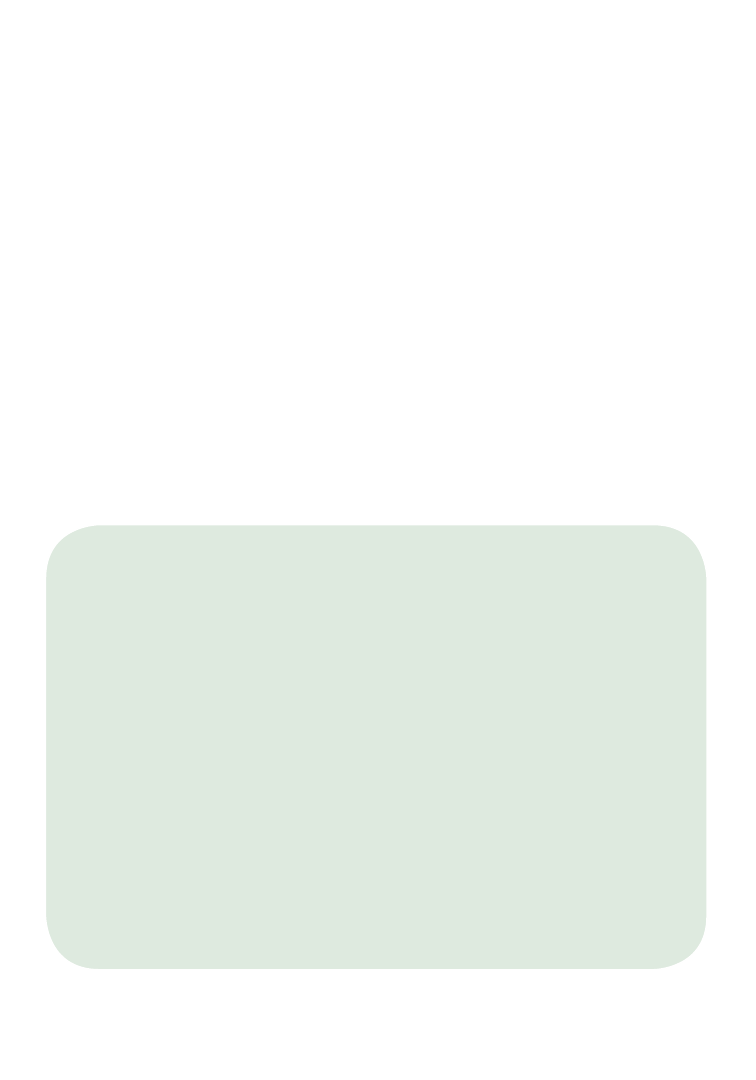

“Texting trees” are denoted by wooden signs

(Figs. 3 and 4). Each sign displays the tree’s

phone number and information regarding the

project, study, and consent. Fourteen trees,

each with their own volunteer tree-speaker

and personality, are spread throughout the

Gardens. There is also a silent Wish Tree,

which people can send their wishes to via text.

Communication is enabled through a cloud-

based system called Zendesk and monitored by

the project head. Each volunteer was provided

with training on the communications system.

Figure 1. Julietta Sorensen Kass (left) and

Anna Irwin-Borg spent many an hour discuss-

ing logistics and media strategies.

Figure 2. When Text-A-Tree was first conceived,

it was a crazy idea and a few sketches. We wanted

our logo to reflect where the journey began.

Figure 3. The first tree we named was a yellow

birch called Tree Tree O’Hara, named after a

famous drag queen, due to the tree possessing

both male and female flowers.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

158

Volunteers were also briefed on urban forest

research, biological and cultural information

regarding their tree species, and facts

pertaining to their unique tree. Using this

information, volunteers created personalities,

complete with pronouns. The entire process

was designed to help participants in the project

recognize trees as individuals, allowing them

to develop a relationship with trees, and view

them as living members of the community.

Attributing trees with personhood may appear

strange in dominant Western culture, but

such a view has roots across time and space

(Boyer, 1996; Bird-David, 1999; Tam et al.,

2013; Tam, 2014; Legge and Robinson, 2017).

One example with particular significance to

Halifax is that of the Mi’kmaq concept of Msit

No’kmaq (translated to “all my relations”).

In this, animals, plants, and even geographic

locations are recognized as having an identity,

personality, and spirit (Robinson, 2014). These

entities are considered persons, in that they

experience their existence in the first person

(Legge and Robinson, 2017).

Mi’kmaq culture was further incorporated

into the project, with 4 of the 15 trees being

selected due to their cultural significance.

These trees boast both their English and

Mi’kmaq names on their signs and initiate

texts to participants with the word “Kwe,” a

Mi’kmaq greeting meaning “I am here” (T.

Christmas, personal communication, June

2019). Through their conversations with

participants, the volunteers representing

these trees share how trees have contributed

to culture in Nova Scotia.

Both the Halifax Public Gardens and the

City of Halifax itself also have a connection

to Japan, which made Japanese culture

important to incorporate as well. Again,

4 of the 15 trees were selected based on

significance to Japanese culture, and these

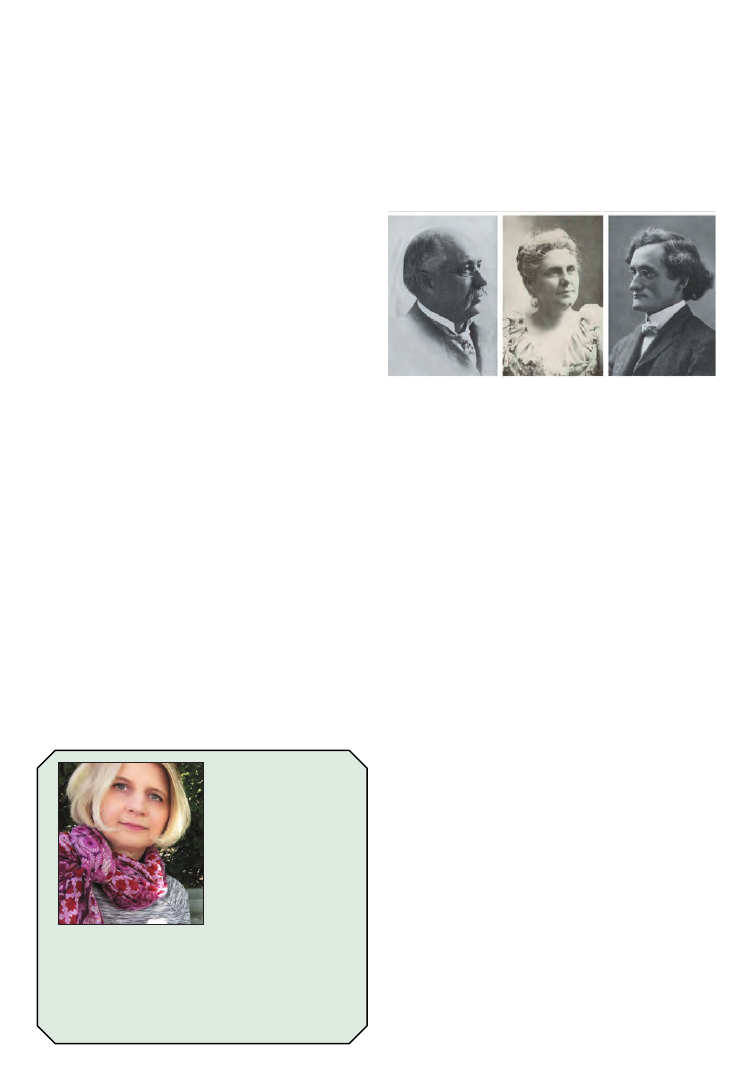

trees now greet participants with Kon’nichiwa

(hello!) and share cultural information (Fig.

5). As an additional recognition of Japanese

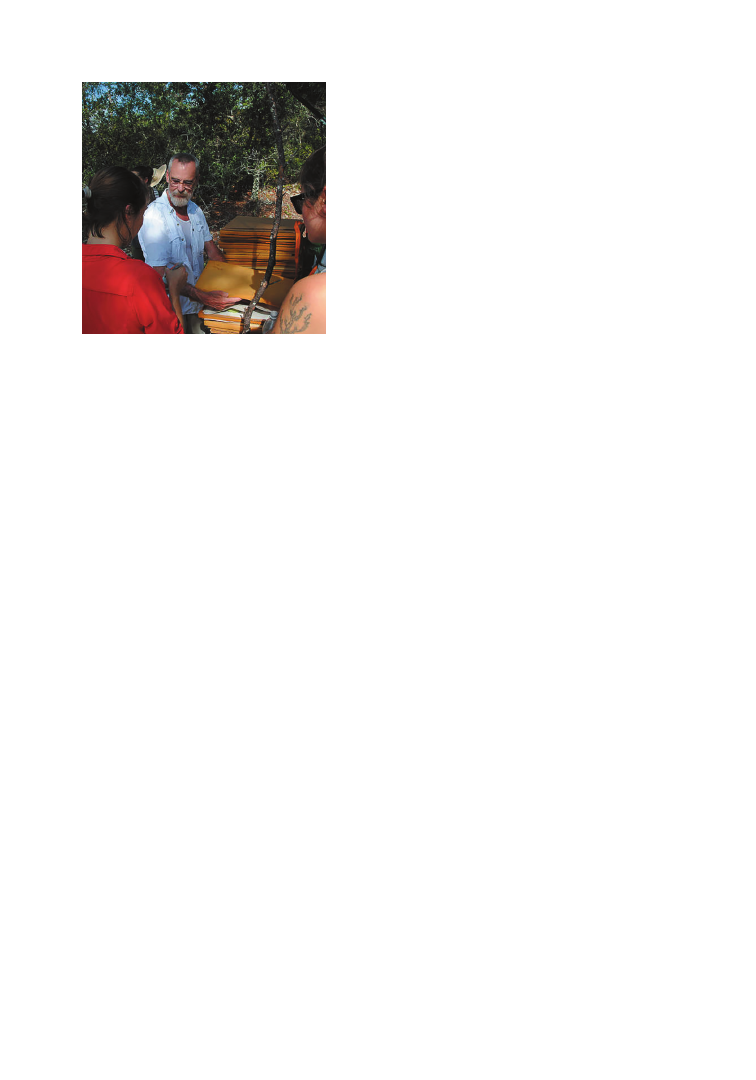

Figure 4. Volunteers were heavily involved

from the beginning. Here we are preparing all

15 signs for our textable trees at the Halifax

Public Gardens.

Figure 5. An early summer shot of Maggie the

Magnolia, one of our 15 textable trees, and a

nod to Japanese culture.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

159

culture, Text-A-Tree was launched on July

7 to coincide with the Tanabata festival. We

partnered with the Dalhousie Japanese Society

to put on a small celebration, including

Japanese crafts, games, and stories. In keeping

with tradition, members of the public were

invited to wish upon the Wish Tree, although

with their phones rather than the customary

tanzaku (long strips of paper). The Wish Tree

has continued to receive wishes and will do so

throughout the project. Anonymous wishes

are posted daily on Facebook and Instagram

(@TextATreeHalifax).

The emphasis on culture is intended to make

Text-A-Tree accessible to the diverse peoples

living in and visiting Halifax. By celebrating

different cultures, we hope to create a space

for people from any background to participate

and share their values. Previous studies have

engaged in street-side interception surveys,

which, by necessity, capture information

from individuals old enough (over 18) and

comfortable with surveys (e.g., Ordóñez et

al., 2016, 2017). Building on the foundation

of this work, we propose that text messaging

might allow younger participants and those

less comfortable with English, or perhaps

intimidated by the prospect of an interview

with university members, to express their

views as well.

Though proper analysis has just begun in

September 2019, initial engagement seems

promising. One week after the launch of

Text-A-Tree, volunteers had engaged in over

1000 unique conversations from participants.

While some have been clear in voicing why

trees are of value---for example, through

comments on beauty, shade, and health---

others have responded with questions and

have been delighted by the information

provided by our volunteers. The data will

likely reveal more surprises still, but for now,

it seems there is hope that technology may

help people reconnect with urban nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was made possible thanks to

the support of the Nova Scotia department

of Communities, Culture, and Heritage, the

Suellen Murray Educational Bursary, and The

Friends of the Public Gardens.

LITERATURE CITED

Barlett, P. F., E. N. Anderson, J. C. Boyer, D. Brunck-

horst, T. Princen, and P. B. Barlett. 2008. Reason

and reenchantment in cultural change: Sustainabil-

ity in higher education. Current Anthropology

49(6): 1077-1098.

Berry, S. 2019, Jan 30. Grow your very own Agave

Maria with seed from celebrity plant. CBC News,

Nova Scotia. Retrieved from: https://www.cbc.ca/

news/canada/nova-scotia/grow-agave-maria-seeds-

celebrity-plant-public-gardens-1.4998366.

Bird-David, N. 1999. “Animism” revisited: person-

hood, environment, and relational epistemology. Cur-

rent Anthropology 40(S1): S67-S91.

Boyer, P. 1996. What makes anthropomorphism natu-

ral: Intuitive ontology and cultural representations.

Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 2(1): 83-

97.

Galle, T. 2016, Aug 8. Talking tree case video. [Video

file]. Retrieved from:

https://www.youtube.com/

watch?v=jMcV0OHBa18.

Lafrance, A. 2015, July 10. When you give a tree an

email address. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://

www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/07/

when-you-give-a-tree-an-email-address/398210/.

Legge, M., and M. Robinson. 2017. Animals in In-

digenous spiritualities: Implications for critical social

work. Journal of Indigenous Social Development 6(1):

1-20.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

160

Ordóñez, C., T. Beckley, P. N. Duinker, and A. J. Sin-

clair. 2017. Public values associated with urban for-

ests: Synthesis of findings and lessons learned from

emerging methods and cross-cultural case studies. Ur-

ban Forestry & Urban Greening 25: 74-84.

Ordóñez, C., P. N. Duinker, A. J. Sinclair, T. Beckley,

and J. Diduck. 2016. Determining public values

of urban forests using a sidewalk interception survey in

Fredericton, Halifax, and Winnipeg, Canada. Arbori-

culture & Urban Forestry 42(1): 46-57.

Robinson, M. 2014. Animal personhood in Mi’kmaq

perspective. Societies (4.4): 672-688.

Statistics Canada. 2014. Canada’s rural population de-

clining since 1851. Canadian Demography at a Glance.

Catalogue No. 98-003-X. Retrieved from: https://

www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-

x2015004-eng.htm.

Tam, K. P. 2014. Anthropomorphism of nature and ef-

ficacy in coping with the environmental crisis. Social

Cognition 32(3): 276-296.

Tam, K. P., S. L. Lee, and M. M. Chao. 2013. Saving

Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connected-

ness to and protectiveness toward nature. Journal of

Experimental Social Psychology 49(3): 514-521.

Vining, J., M. S. Merrick, and E. A. Price. 2008. Hu-

man perceptions of connectedness to nature and ele-

ments of the natural and unnatural. Human Ecology

Review 15(1): 1–11.

FROM THE

PSB

ARCHIVES

60 years ago: “A survey has been made of what bacteriology teaching and research assistants were being

paid at 34 colleges and universities during the year 1958-59 [. . .]

For teaching assistants the number of hours of work per week ranges from 8 to 22 with most places re-

quiring 15 to 20. Just half of the institutions use teaching assistants for 9 months. About half of the remainder

have 10 months appointments, the rest 12 months. There is great variation in the number of hours of graduate

work that assistants are allowed to carry, but an estimate would be that two courses through the year is what

the figures mean. Fifteen institutions charge teaching assistants no fees. In the others, particularly those with

charges for out-of-state students, fees may run as high as $400 for the academic year (and these institutions do

not necessarily have the highest stipends for teaching assistants). [. . . ]

The stipends for Teaching Assistantships for 9 months run from under $1000 (2 institutions) to just over

$2000 (1 institution).

- Creighton, Harriot B. “ASSISTANTS’ SALARIES 1958-59” PSB 5(5): 7

[Editor’s Note: Online inflation calculators (e.g. Calculator.net) indicate that this would be approximately

$8,700 to $17,500 in 2019 dollars.]

50 years ago: “Dr. Charles Heimsch, retiring Editor of the American Journal of Botany, presented a report

on the current status of the Journal and a summary of certain aspects of the Journal operation during his 5-year

tenure as Editor.” In 1969, 153 manuscripts were published and 28 were rejected.

- Starr, Richard C. “Minutes of the Business Meeting” PSB 15(4): 7

PSB 65 (3) 2019

161

N

ature study, as we have come to

understand it in the 21st century, is an

umbrella term used to encompass education

about our environmental world. It is a course

of biological study that introduces the curious

student to introductory levels of botany,

zoology, entomology, and the study of other

living systems. Nature study may be the

initiation of an educator’s enthusiasm, in any

of these disciplines, to raise his or her students'

curiosity.

Here, I seek to tell the story of a collective

group of nature educators, with a predilection

toward botany, who were inspired and

influenced by Cornell University nature study

educator, Anna Botsford Comstock, and her

husband John Henry Comstock, entomologist

and educator, at the turn of the 20th century.

The three notable educators—Liberty Hyde

Bailey, Anna Botsford Comstock, and John

Walton Spencer (Fig. 1)—mentored four

young women to seek their own paths

and establish their botanical legacy. (It is

noteworthy that Bailey was an early member

Inspirational Voices in

Early Botanical Education

and past-president of the BSA.) The stories,

or at least the botanical marks, of Alice

Gertrude McCloskey, sisters Julia Rogers and

Mary Rogers Miller, and Ada Eljiva Georgia

are preserved in Mrs. Comstock’s original

unpublished autobiographical manuscript.

The 1953 autobiography, The Comstocks of

Cornell, was drastically altered when Mrs.

Comstock’s manuscript was culled in the

years following both Comstocks’ death by

several Cornell personalities who sought

to elevate Prof. John Henry Comstock’s

entomological legacy (St. Clair, 2017) at

the expense of Anna B. Comstock’s own

legacy. The collective botanical and nature

study work of this group of seven educators

overlapped in their individual projects and

through collective ventures. Following their

stories is a bit convoluted, yet astonishing in

the closeness of their connection. Here I hope

to bring their stories back into the light, and

to recognize them for their contributions, as

Anna B. Comstock intended.

By Karen Penders St. Clair

School of Integrative Plant Science, Plant

Biology Section, Cornell University, Ithaca,

NY 14853

E-mail: aka27@cornell.edu

Figure 1. John Walton Spencer, Anna Bots-

ford Comstock, and Liberty Hyde Bailey circa

1904.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

162

LIBERTY HYDE BAILEY,

ANNA BOTSFORD

COMSTOCK, AND

JOHN WALTON SPENCER

Anna B. Comstock began her career at

Cornell University in the late 19th century, in

collaboration with the entomological research

of her husband, John Henry Comstock, and

spread collaterally when she partnered with

the agrarian zeal of Bailey. The scope of

Bailey’s work is an article unto itself. For our

purposes here, it will suffice to say that Bailey

came to Cornell in 1888 as Chair of Practical

and Experimental Horticulture. His work

in nature education and outreach, during

the early 20

th

century, came at the heels of

an accomplished botany and horticulture

education, including a two-year herbarium

assistantship to the distinguished botanist,

Asa Gray, at Harvard University (Lawrence,

1955). Bailey wrote six botany textbooks

between 1898 and 1909; however, one of his

first books, Talks Afield (1885), was a botany

book written for the farmer and non-scientist.

Bailey founded the College of Agriculture at

Cornell, and served as the dean of the New

York State College of Agriculture from 1903

until his retirement from the University in

1913 (Lawrence, 1955).

The ink of the Nixon Act of 1896, which

allowed funding for extension courses in

horticulture, had barely dried as Bailey and

Anna B. Comstock traveled by horse and

buggy visiting rural schools of New York

State (Anna B. Comstock, unpublished).

In meeting with teachers in Cattaraugus

County, New York, they discovered John

Walton Spencer in Westfield, New York, and

believed him to be a man who seemed to

have the qualities needed to develop further

work on the Nature Study

program (Palmer,

1944). Spencer came to Cornell University

on a voluntary basis in 1896, at the behest

of Bailey. The Nature Study movement from

Cornell took off like a firestorm around the

country upon Spencer’s inclusion. Letters

from superintendents around the country

proclaimed enthusiastically to procure from

Spencer every copy of the Nature Study

circular letter for all their teachers (Spencer,

1898). This circular was developed by Spencer

while at Cornell University.

Spencer was passionate about his work in

Nature Study and lectured around New York

State in various schools of local townships.

He wrote about several topics regarding

Nature Study, and particularly with plant-

based lessons such as The Apprentice Class

in Gardening out of door work; Elementary

Gardens out of doors; Sowing a Seed; Plant

Life; Soils; Autobiography of a Corn Stalk;

Fall Planting for Outdoor Growth; Plants

that prepare lunches for their offspring; Seed

dispersal; Perennials for the School Ground; A

Bulb Garden; and How to Help Plants Grow

(Spencer, 1898).

In addition to impact among adults, Spencer’s

essays and circulars were important for

promoting gardening and nature study

among the youth. In his essay What is Nature-

Study?, Bailey stated that Spencer was largely

responsible for the fruition of the children’s

garden movement in New York largely due to

his efforts to put children in touch with nature

in their daily lives through the development of

Junior Naturalist Programs. This program was

a subscription-based incentive for teachers

and students to get pamphlets and information

about nature studies. It is here where we are

first introduced to Alice Gertrude McCloskey,

who, with Spencer, organized Junior Naturalist

Clubs with the idea of organizing children

PSB 65 (3) 2019

163

into clubs for the study of plants and animals,

and other outdoor subjects (Bailey, 1897).

ALICE GERTRUDE

MCCLOSKEY

John Spencer first met Alice Gertrude

McCloskey in Saratoga Springs, NY during

his travels around the state for his Junior

Naturalist Programs. She had so impressed

Spencer with her work in nature education in

the schools that he recruited her to come to

Cornell University to assist in answering the

inquiries that were coming in from his junior

naturalists. McCloskey came to Cornell in the

fall of 1899 and was appointed an Assistant in

Nature Study (Cornell Alumnae Club, 1915).

At the instigation of Bailey, Spencer, with

McCloskey, encouraged Cornell agricultural

faculty to write to children in the country in

an effort to build comradery between farm

families and the University. McCloskey was

the one “who first used the phrase” Cornell

Rural School Leaflet (quote from Palmer,

1944).

In an unpublished account from July 1900,

during a summer session at Chautauqua

Institute for Nature Study teaching, Anna B.

Comstock observed, “Mr. John Spencer and

Alice McCloskey were also there for the Junior

Naturalist and gardening work. I saw Mr.

Spencer give a practical lesson in gardening

to kindergarten children and I marveled at

this success and his charm for the little folk.”

(Anna B. Comstock, unpublished).

Overlapping this work, from 1899 to 1904,

McCloskey was co-editor of the Junior

Naturalist Monthly with Comstock, and

worked with Spencer on developing and

implementing lessons (Anna B. Comstock,

unpublished Chapter 10, p. 18). McCloskey,

Anna B. Comstock, Rogers, and Spencer also

collaborated on the Cornell Reading-Course

for Farmers as part of their extension work. At

the time a group of 20 people represented the

New York Experiment Station and University

Extension Staff. In 1900, members of this

staff were already working together on the

Home Nature-Study Course as part of the

Cornell Reading-Course for Farmers (Cornell

University, 1902 [Cornell Ag Exp St, 1894-

1911]).

The Reading-Courses were precursors to

the Cornell Nature-Study Leaflets, which

were later distributed by Bailey. McCloskey

contributed 20 of the 30 leaflets written for

children with Bailey, Anna B. Comstock,

Spencer, and others covering the remaining

10. The individual educational leaflets were

succinct and guided the educator through

basic methods of instruction and encouraged

observation by the child. Half of the 30

children’s leaflets are botanically focused.

McCloskey wrote half of these botanical

modules herself, which included Maple Trees

in Autumn (1903), A Corn Stalk (1903), In the

Corn Fields (1903), Jack-in-the-Pulpit (1903),

Twigs in Later Winter (1904), Pruning (1904),

The Hepatica (1904), and Dandelion [with

Bailey] (1904) (New York State Department

of Agriculture, 1904).

MARTHA VAN RENSSELAER

AND

THE BOYS AND GIRLS

LEGACY

The Comstock-Bailey association was the

synergistic catalyst that also pulled Martha

Van Rensselaer to Cornell. Recruited by

PSB 65 (3) 2019

164

Bailey, at the request of Anna B. Comstock,

to come help organize a reading course for

farmers’ wives, Van Rensselaer was a New

York State native in her third term as School

Commissioner for Cattaraugus County. She

already had early contact with Spencer, asking

for circulars to distribute at a forthcoming

meeting of the Teacher’s Association (Fig.

2). Van Rensselaer held such a staunch

commitment to the Cornell nature and rural

education programs that she wrote Spencer of

her readiness to answer the call to come help

(Spencer, 1897-1912, Box 2).

Figure 2.

An etching gifted to Martha Van

Rennselaer by Anna B. Comstock (“To Mar-

tha Van Rennselaer – with love – from the en-

graver & artist-”).

Under Spencer, part of the reorganization of

educational efforts in 1902 included Anna

B. Comstock and Van Rensselaer with their

collective venture of the Boys and Girls

magazine. It is at this point that McCloskey

returned to her classes at the University,

although she also contributed eight articles

to Boys and Girls magazine, on other nature

topics, until it ceased publication in 1907.

Anna B. Comstock, Spencer, and Van

Rensselaer’s early nature writing, through their

joint publication of Boys and Girls, maintained

their educational base in nature study at

Cornell. This annual publication served as

a platform for botanists, horticulturalists,

zoologists, and agricultural specialists to

interact with parents, teachers, and children

in distant communities. The Boys and Girls

nature magazine was not only an important

source to reach children outside of New York

State, but also served as a stepping stone

of publication for young women under the

direct influence of both Spencer and Anna B.

Comstock. First published in 1901, Boys and

Girls was the brain-child of Van Rensselaer in

conjunction with Spencer (Percival, 1956). At

the beginning of her auspicious career, Van

Rensselaer, already acquainted with Spencer

from her early Commissioner days, approached

him with the idea of producing a publication

about garden, home, and nature education.

Anna B. Comstock, in turn, was approached

by Spencer with a proposal to join as editor,

adding not only her own stories and artwork,

but the “Comstock” name to the venture.

Unlike the Home-Nature Study Course, under

the general direction of Mary Rogers Miller

(see below), running concurrently at the time,

the idea for the Boys and Girls publication was

one that would interact directly with children.

Building on the “Uncle John” precedent of the

Junior Naturalist Clubs, the goal of this new

format would be to endeavor to reach children

beyond New York State.

The little magazine was published for five

years with Van Rensselaer taking over as

editor in 1903 as Anna B. Comstock shifted

her energies to the Home Nature Study

Course leaflets at Miller’s resignation (Anna

B. Comstock, 1907).

1

Comstock maintained

her influence on Boys and Girls not only with

PSB 65 (3) 2019

165

her own submissions, but also as a direct

channel for other young women to have a

means to have their own writing published.

McCloskey,

2

Miller (

“Woodland Flowers

in Spring,” Boys and Girls, April 1904)

, and

Julia Rogers (

“A Winter Landscape,” Boys and

Girls, February 1904)

all submitted articles

and essays to Boys and Girls, contributing to

nature study education movement into the

early 20th century.

MARY FARRAND ROGERS

MILLER

Mary Farrand Rogers Miller was the younger

of the two Rogers sisters who held a lifelong

relationship with the Comstocks (Fig. 3).

Miller was born and raised on a farm in Dallas

County, Iowa in the mid-1860s. Her strong

roots in rural life gelled compatibly with the

surging nature study education movement of

the time. Miller taught in rural, village, and

city schools both in Iowa and Minnesota from

the age of 17 (Cornell Alumnae, 1909). Miller

came to Cornell University in 1893, choosing

to “study the facts of life in biology laboratory

with men and women working together

matter-of-factly” (Miller, 1954). Miller met

John Comstock almost immediately at the

beginning of the Spring 1893 session at Sage

Hall, where Miller lived and Comstock took

his meals when his wife traveled (Anna B.

Comstock, unpublished Chapter 9, pp. 14–

15). An excellent student, Miller became

determined by the following spring of 1894

to study entomology. She and her colleagues

kept the professor on his toes as he met the

demand for his growing department in what

was the largest ever registered for the third

term in entomology (Anna B. Comstock,

unpublished Chapter 9, pp. 25-26). In 1896, her

senior year at Cornell, Miller was appointed

to the position of laboratory assistant in the

department of entomology and continued in

the capacity of an instructor for the summer

term.

In the following fall of 1896, winds of change

began to blow for the College of Agriculture

at Cornell. As stated previously, it was in this

year that the Ways and Means Committee of

the New York State Legislature appropriated

funds to Cornell University to expand the

nature study education initiative at the College

of Agriculture. This appropriation was an

expansion from the 1894 establishment of

extension courses in horticulture with

Cornell teachers in Chautauqua County of

New York (Anna B. Comstock, 1953; Anna

B. Comstock, unpublished, Chapter 10, p. 3).

The Bureau of Nature Study began an issuance

of leaflets immediately in December 1896.

The early leaflets were known as the Teacher

Leaflets with both Anna B. Comstock and

Miller contributing articles accordingly. The

Teacher Institute leaflets that Miller oversaw

reached 30,000 teachers (Palmer, 1944).

In 1897, Miller was appointed Lecturer in

Nature Study as Cornell began its extension

Figure 3. Mary Farrand Rogers Miller (Cor-

nell Alumni News, 1909) and Julia Ellen Rog-

ers (Class of 1892, University of Iowa).

PSB 65 (3) 2019

166

work in the College of Agriculture, and for a

brief time commanded a higher salary than

Anna B. Comstock herself (Kohlstedt, 2005).

3

It was a position that Miller held for six years

during which

time she also taught at Cornell

Summer School with the rank of Instructor.

Miller also appeared on the programs of the

National Education Association of the New

York State Science Association, and of the

American Association for the Advancement

of Science (Cornell Alumnae, 1909). Miller’s

relationship with Anna B. Comstock

intertwined as they both taught nature study

at the State Normal School at Chautauqua,

and she, along with her sister, Julia, lived with

Anna B. Comstock during these summers

away from Ithaca. The Rogers sisters were not

just any students with a marginal relationship

to the Comstocks; they formed an important

part of the Comstock household (Comstock,

unpublished Chapter 10, pp. 10, 17, 23).

Miller’s name appeared at the onset of the

project as the Nature Study educator as part of

the organization of the Station and University

Extension Staff. She contributed annually to

the Teacher Leaflets until their publication

ceased in 1901 (

New York State Dept. of

Agriculture, 1904

). With the cessation of one

project, Miller was free to complete another.

Her book, The Brook Book: A First Acquaintance

with the Brook and its Inhabitants Through the

Changing Year, was first published in 1901.

Dedicated to “John Henry Comstock”

4

, the

book is expressive with its execution of a prose

of deep reflection and introspection. Miller

wrote in a semi-autobiographical format,

as her unnamed protagonist hiked through

wooded wetlands with “the Professor.” Her

writing anthropomorphized the brook with

the courses of a human life. The wife of

Cornell horticulturist, William (Wilhelm)

Tyler Miller,

5

Miller’s The Brook Book has

an appeal to the botanist, entomologist, and

naturalist alike as the chapters alternately

weave each discipline in concert with each

other. The symbiotic relationship of plant,

insect, and animal in this slim volume is a

treasure.

The termination of the Teacher Leaflets

program in 1901 was more of a hiatus than

an end-point for the educators involved

with its writing. Each educator evolved their

direction, guided by the demands of the

teachers for whom they wrote their nature-

education modules. The nature study work at

Cornell continued with Liberty Hyde Bailey

appointing Miller as the general director of

the Home Nature Study course in 1902 as well

as assistant editor of the magazine Country

Life in America (a position she maintained

through October 1909) (

Cornell Alumnae,

1909).

Miller contributed several articles to

the Home Nature study course, but her tenure

was short-lived as her husband’s career pulled

the couple in a new direction, away from

Ithaca, New York in 1903.

6

For several years

before her death, at age 103, in 1971, Miller

was noted as the oldest living Cornell alumna

(Edward D. Cobb, personal communication).

JULIA ELLEN ROGERS

Little is known of Julia Ellen Rogers, the

older of the two sisters, whom the Comstocks

took to their hearts. At the end of the 19th

century, Julia was known as a prominent

nature study educator in the state of Iowa.

Her collaboration with members of the Iowa

Agricultural College was part of the nature

study education movement being introduced

in the west as well as an early attempt to

compile seven nature study lessons in booklet

form for classroom teachers. Her contribution

PSB 65 (3) 2019

167

of “A Nature Study Lesson on the Grasshopper”

to the Iowa-based booklet hints to the

collaboration that lay a decade in her future.

7

Scant documentation exists to indicate

exact dates of Rogers’ migration east. The

pull eastward may have been great with the

prospects of a college education influenced by

Julia’s younger sister, Mary (Farrand) Rogers

Miller, and her senior thesis work with John

H. Comstock. The notoriety of both the

Comstocks’ work in nature study education,

particularly of Anna B. Comstock, would have

been known to Rogers as well and may have

been an incentive to come to Cornell.

Rogers enrolled in Cornell in 1900 and

worked closely with John H. Comstock on her

master’s thesis of Materials for Winter Work

in Nature-study (1902) (Rogers, 1902; Cornell

University, 1908). In what is one of the few

existing documents to reflect Rogers’ voice,

the introductory remarks of her thesis speak

directly toward the influence and importance

of the Nature Study Program lauded by Anna

B. Comstock at that time. She emulated

Anna B. Comstock both with positive and

encouraging paragraphs about the importance

of the thoughts of a child’s own observations,

and of the knowledge such observation incurs.

Rogers with her sister Mary Miller were

considered members of the Comstock

household. Both young women traveled with

Anna B. Comstock to southern New York

State for the summer nature study lectures at

Chautauqua Institute. Julia would stay with

Anna B. Comstock when John H. Comstock

would travel for his work (Anna B. Comstock

unpublished, Chapter 10, p. 23). A self-

described publisher, Rogers was a prodigious

writer; her article, “Boys & girls, as naturalists,

gardeners, home-makers, citizens,” contributed

to Boys & Girls: A Nature Study Magazine, was

to be the first of several articles and books that

Rogers was to write in her career (Comstock,

1907).

Rogers’ entomological beginnings

took a decidedly botanical turn with seven of

her ten publications following her botanical

interest. These include:

• Among Green Trees: A Guide to Pleasant

and Profitable Acquaintance with Familiar

Trees (1902; A. W. Mumford: Chicago);

• Tree Book: A Popular Guide to a Knowl-

edge of the Trees of North America and to

Their Uses and Cultivation by Julia Ellen

Rogers (1905; Doubleday, Page & Com-

pany: New York);

• Book of Useful Plants by Julia Ellen

Rogers. Illustrated by Thirty-One Pages

of Half-Tones from Photographs (1913;

Doubleday, Page & Company: New York);

• Useful Plants Every Child Should Know

(1913; Doubleday, Page & Company:

New York);

• Tree Guide: Trees East of the Rockies by

Julia Ellen Rogers (1916; Doubleday, Page

& Company: New York);

• Canadian Trees Worth Knowing (1917;

The Musson Book Co.: Toronto);

• Trees Worth Knowing (1917; Doubleday,

Page & Company: New York);

• Trees (1926; Doubleday, Page & Com-

pany: New York).

Little more is known of Julia Rogers save for

her writing. It is known that Rogers eventually

settled in later life, first in New Jersey, near

her sister Mary, and then in California where

her interest turned to seashells and their

identification (Cornell University, 1908).

After her death in 1958, Rogers’ remains were

interred in her home state of Iowa.

PSB 65 (3) 2019

168

ADA ELJIVA GEORGIA

Ada Eljiva Georgia came to Ithaca, NY, to join

John Spencer as his assistant in the early days

of nature study education in 1896 (Fig. 4).

Spencer discovered Georgia as a teacher in the

city schools of Elmira, New York, engaged in

nature study work with her classes (New York

State College of Agriculture, 1921). Little is

known about Georgia’s background up until

this time; however, her affiliation with Cornell

University was through nature study initiatives

she worked on in collaboration with Anna B.

Comstock and others.

Figure 4. Alice Gertrude McCloskey and

Ada Eljiva Georgia

(Images from Cornell Nature Study Leaflets,

Fall 1956, Vol. 50, No.1.)

Georgia joined Anna B. Comstock in

producing the Home Nature Study Course

leaflets in 1906 when she was transferred to

Anna B. Comstock’s office. With her, Georgia

brought a sound knowledge of plants that

added tremendously to the writing of the

leaflets and assisted in the answering of letters

that Anna B. Comstock had been diligently

working on alone, in the three years before the

arrival of both Spencer and Georgia. Georgia’s

memory was vast, her interests many, and her

love of literature provided many of the literary

references to Anna B. Comstock’s superb

Handbook of Nature Study (Trump, 1954).

Through her associations with Spencer, Anna

B. Comstock, and in turn with Bailey, Georgia

published a large tome with the MacMillan

Company in October 1914 that was edited by

Bailey. The book, A Manual of Weeds (1914),

was part of a collection of books called The

Rural Manuals edited by Bailey. Georgia’s book

contains 385 illustrations from wildflower

author F. Schuyler Mathews and is dedicated

to the memory of her mentor, Spencer, who

died in 1912.

8

Georgia describes herself as

“an assistant in the farm course” on the front-

piece of her book, yet Spencer and Anna B.

Comstock’s influences are evident in that

Georgia endeavored to make her book “less

technical and easier for the general reader to

understand.”

The preface of A Manual of Weeds safeguards

the only words that are truly Ada Georgia’s

own thoughts or philosophies. The writing is

lyrical and resonant of both Bailey’s and Anna

B. Comstock’s own writing styles:

“... Dame Nature is an ‘eye-servant’; only by the

sternest determination and the most unrelaxing

vigilance can her fellow-worker subdue

the earth to his will and fulfill the destiny

foreshadowed in that primal blessing, so sadly

disguised and misnamed, when the first man

was told, ‘Cursed is the ground for thy sake; in

sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life;

thorns also and thistles shall it bring forth to

thee; and thou shalt eat of the herb of the field.’

A stern decree.” (Georgia, 1914)

Working with Anna B. Comstock up until her

sudden death in 1921, Georgia was described

by her colleague and friend as a woman of

remarkable character and indomitable spirit

PSB 65 (3) 2019

169

(Anna B. Comstock, unpublished, pp. 17-

37).

9

Additionally, Georgia is saluted by

Anna B. Comstock’s successor, E. Laurence

Palmer, over 20 years after Georgia’s death in

the Cornell Rural School Leaflet of September

1944:

“A debt of gratitude is due to some of those who

served during the early days of Cornell nature

study but who did not have the opportunity

to assume conspicuous places of leadership.

Foremost of these is Ada Georgia, a tireless,

careful, outdoor person with a fundamental

love for children that was not always obvious

to casual acquaintances. As an inadequate

monument to her careful, useful work she left

her Manual of Weeds that was for years a

classic in its field.” (Palmer, 1944)

In the Preface of her Manual of Weeds, Georgia

lastly acknowledged the desire for her work to

be published for the public-at-large as “one of

the few wishes that ‘come true’ …” (Georgia,

1914). This final statement of Georgia’s book

gives a nod toward the importance in which

precedence, influence, and mentoring have

toward the next generation of nature educators,

including botanists, and particularly women,

with the motivation to push forward toward

legacies in their own names.

CONCLUSIONS

This brief historical review of the rich tapestry

of Nature Studies, conducted by dedicated

women and men associated with Cornell

University, attests to the profound influence

that these pioneers had during the early part

of the 20th-century America. Sadly, most of

their writings have gone neglected. Yet, even

a casual reading of the bulletins and books

produced by these once influential scientists

and educators shows that the love and concerns

about the welfare of the natural environment

predates current concerns about the erosion

of our ecosystems and the sustainability of

our world’s biodiversity. It would be remiss of

me not to encourage re-reading the literature

produced by these forward-looking scholars,

for much would be re-learned and perhaps

not forgotten.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A special word of thanks, and appreciation, is

extended to Edward D. Cobb, Karl J. Niklas,

and Randy O. Wayne in the School of Inte-

grated Plant Science/Plant Biology section

of Cornell University, Ithaca, NY for their

mentorship and assistance with photographs.

I also thank two reviewers for the many posi-

tive and constructive comments regarding

my manuscript.

FOOTNOTES

1

“Boys and Girls.” “v. 1-6, v. 7, no. 1-6;

Jan.

1903-July 1907. Caption title: Boys & girls, as

naturalists, gardeners, home-makers, citizens.

Official organ of the Chautauqua junior

naturalist clubs, June 1904-Nov. 1905. Editors:

Jan.-Mar. 1903, Mrs. Anna B. Comstock. --Oct.

1903-July 1907, Martha Van Rensselaer.”

2

What Happened to Freckles: March 1904

(Volume 2, Number 3); A Riddle! Who Can

Guess It?: April 1904 (Volume 2, Number

4); Required Reading for Chautauqua Junior

Naturalists: November 1904 (Volume

3,

Number 3); Required Reading for Chautauqua

Junior Naturalists: December 1904 (Volume 3,

Number 4); Bird Houses: May 1905 (Volume

4, Number 5); For Chautauqua Junior

Naturalists: May 1905 (Volume 4, Number 5);

June 1905 (Volume 4, Number 6); December

1905 (Volume 5, Number 4); Winter Birds:

PSB 65 (3) 2019

170

January

1906 (Volume 6, Number 1); Carrots

in the Schoolroom: January 1907 (Volume 7,

Number 1); Cats: January, 1907 (Volume 7,

Number 1); The Brook and the Brookside: May

1907 (Volume 7, Number 5) (Cook, 2005).

3

The following year, Anna B. Comstock was

appointed Assistant Professor of Nature Study

in the Cornell University Extension Division

on November 10, 1898. This designation was

rescinded in 1899 by the Board of Trustees.

Comstock was then appointed Lecturer in

Nature Study by Cornell President Gould

Schurman (Comstock, unpublished, 10-8).

4

“To JOHN HENRY COMSTOCK Guide,

Philosopher and Friend ALL THAT IS WORTHY

IN THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY

DEDICATED (Miller, 1901).”

5

Wilhelm (William) Miller received his

three degrees from Cornell University (18

96

BS; 1897 AM, 1900 PhD) (Cornell Alumni

News, 1922), and worked on chrysanthemum

research with Liberty Hyde Bailey.

6

State of

New York Department of Agriculture,

Cornell Nature-Study Leaflets. “Mosquitoes”

(1902), “About Crows” (1902), “Pruning”

(1902), “The Life History of a Beet” (1903)

(New York State Dept. of Agriculture, 1904).

7

Iowa State Horticultural Society, John Craig,

and Julia E. Rogers. 1890. Suggestive Outlines

Bearing upon the Introduction of Nature Study

into the Schools of the State / Authorised by the

State Horticultural Society and Prepared by

Members of the Faculty of the Iowa Agricultural

College, Assisted by Julia E. Rogers. Iowa State

Horticultural Society: Des Moines, IA.

8

“To the revered memory of John Walton

Spencer: My employer, teacher, and friend to

whose first suggestion and encouragement the

beginning of this book is due.” (Georgia, 1914).

9

“On January 8th [1921] Miss Ada Georgia

died. She was a remarkable character.

She suffered hardships all her life and her

indomitable spirit carried on despite them. She

was a passionate lover of books, a keen observer

of nature, and an indefatigable worker. She had

been my greatly prized assistant in conducting

the Home Nature Study Course for eight

years. Her devotion to the work and loyalty to

me had made her an important factor in my life

and a valued friend.” (Comstock unpublished,

17-37).

LITERATURE CITED

Bailey, L. H. 1885. Talks Afield: About Plants and the

Science of Plants. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, MA.

Bailey, L. H. 1897. “What Is Nature-Study?” Cornell

Nature-Study Leaflets, Teachers’ Leaflets, No. 6 (May

1): 11–19.

Comstock, A. B. 1907. Boys and Girls: A Nature Study

Magazine. (Edited with Martha van Rensselaer and

John W. Spencer, v. 1-6, v. 7, no. 1–6.) The Stephens

Publishing Co., Columbia, MO.

Comstock, A. B. 1953. Comstocks of Cornell: Biogra-

phy and Autobiography of John Henry Comstock and

Anna Botsford Comstock. (Edited by Ruby Green Bell

Smith and Glenn W. Herrick.) Comstock Publishing

Associates, New York.

Comstock, A. B. unpublished. The Comstocks of Cor-

nell: Biography and Autobiography of John Henry

Comstock and Anna Botsford Comstock. #21-25-27,

Box 8. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections,

Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

Cook, F. W. M. 2005. “Core Historical Literature of

Agriculture (CHLA),” January 3, 2005.

Cornell Alumnae Club of New York, 1909. “Mary