In This Issue...

Student reps’ guide to opportuni-

ties for students in 2016.... p.151

Conservation challenges in

Canada’s Nisku Prairie.... p. 140

What are the best practices on

interacting with NSF?... p. 131

PLANTS Grant Recipients and Mentors Gather at Botany 2015!

FALL 2015 VOLUME 61 NUMBER 4

BSA President Richard Olmstead on Increased International Cooperation in Botany

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

A PUBLICATION OF THE BOTANICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA

Fall 2015 Volume 61 Number 4

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 61

Kathryn LeCroy

(2018)

Environmental Sciences

University of Virginia

Charlottesville, VA 22904

kal8d@virginia.edu

L.K. Tuominen

(2016)

Department of Natural Science

Metropolitan State University

St. Paul, MN 55106

Lindsey.Tuominen@metrostate.edu

Daniel K. Gladish

(2017)

Department of Biology &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Biology Department

Division of Health and

Natural Sciences

Holyoke Community College

Holyoke, MA 01040

cwetzel@hcc.edu

Melanie Link-Perez

(2019)

Department of Biology

Armstrong State University

Savannah, GA 31419

melanie.link-perez@armstrong.edu

From the Editor

With this December 2015 issue, I am delighted

to unveil a new look and a new logo for the Plant

Science Bulletin. Botany is a dynamic, evolving sci-

ence and it is fitting for the Plant Science Bulletin-

to continually grow and change together with the

field and with its readers. The BSA staff and I have

been working hard to develop a new layout to fit

within a larger 7 x 10-inch format. It is our hope

that this new format will be attractive, improve

readability of the popular print version of the PSB,

and facilitate digital access of PSB content.

To accompany this new layout for the print PSB,

we will be redesigning the Plant Science Bulletin

webpage (http://botany.org/home/publica-

tions/plant-science-bulletin.html), where you can

easily access the most recent issue of the PSB, the

PSB archives, as well as recent BSA news items and

books currently available for review. Rob Brandt

and the BSA team will be adding additional web

features in the coming months. Check the PSB

page often for updates and for newly available

books!

Within this issue, I would like to draw your atten-

tion to valuable resources for both professional

and student members. You will find an in-depth

article (page 131) about the policies and proce-

dures at the National Science Foundation with tips

for preparing grant proposals. In the Student Sec-

tion (page 151), the student representatives pres-

ent an extensive list of grants and awards, as well as

outreach, training, and professional opportunities

aimed primarily at students. Finally, the Botanical

Society of America is calling for nominations and

applications for several awards that are relevant to

members in all stages of their careers (page 130). I

hope that you consider applying for these awards

or nominating your worthy colleagues.

120

SOCIETY NEWS

The International Botanist

Remarks by President-Elect Dick Olmstead

(Note: The video and slides from this lecture

from the Botany 2015 conference can be found

on the BSA’s Botany Conference YouTube chan-

nel at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hr-

lA43io0CQ.)

I

had an epiphany of sorts one rainy night in

2009 during a long treacherous microbus

ride while conducting fieldwork in the Peru-

vian Andes. A British woman seated next to

me explained why she had spent the last six

months volunteering and traveling in rural

Peru by saying that it wasn’t the immediate

experience that was most important to her,

but rather the lasting impact on her life of ex-

periencing the culture of a foreign country,

about which she would never feel the same

again. Months later, I realized just how true

this is. Ostensibly the reason for my travel

was to collect plants for my research, but after

the passage of time, the memories that stayed

with me were of people and places. Ironical-

ly, my personal history of international travel

began in Peru 41 years earlier as an exchange

student living in Lima and taking advantage

of the opportunity to travel and learn about

the country.

As my career as an academic botanist devel-

oped, that interest in travel served me well as

research interests in plant phylogenetics led

me to visit far-flung parts of the world and

to interact with scientists from around the

world. I would like to relate two of those expe-

riences, because I think they are illustrative of

the tremendous advantages that international

cooperation can yield.

International Research

Collaboration on Verbenaceae

Over the past 13 years, I have been involved

in research on the verbena family. This work

has taken me and/or my students to more than

a dozen countries. Botanists in each country

helped negotiate legal and cultural barriers. In

return, field trips with host country botanists

resulted in the collection of hundreds of plant

specimens for their herbaria and ours. But

equally importantly, the personal connections

that enhance the outcomes of the research

afford a marvelous opportunity for cultural

education of everyone involved. The tangible,

scientific outcomes of this project, which is

still ongoing, include collaboration among 18

scientists from five countries in research pub-

lications; Ph.D. degrees to six students from

five countries, whose research benefited from

Botany 2015

Presidential Address:

Richard Olmstead: The

International Botanist

PSB 61 (4) 2015

121

the collaboration; international research ex-

change opportunities for three grad students;

numerous undergraduate participants; and

presentations at four international confer-

ences (as well as our Botany meetings). I ben-

efitted from their expertise and knowledge of

the local plants, while my collaborators ben-

efitted from the opportunity to participate

in high-impact publications (including sev-

eral in the American Journal of Botany) that

emerged from the collaboration (Figure 1).

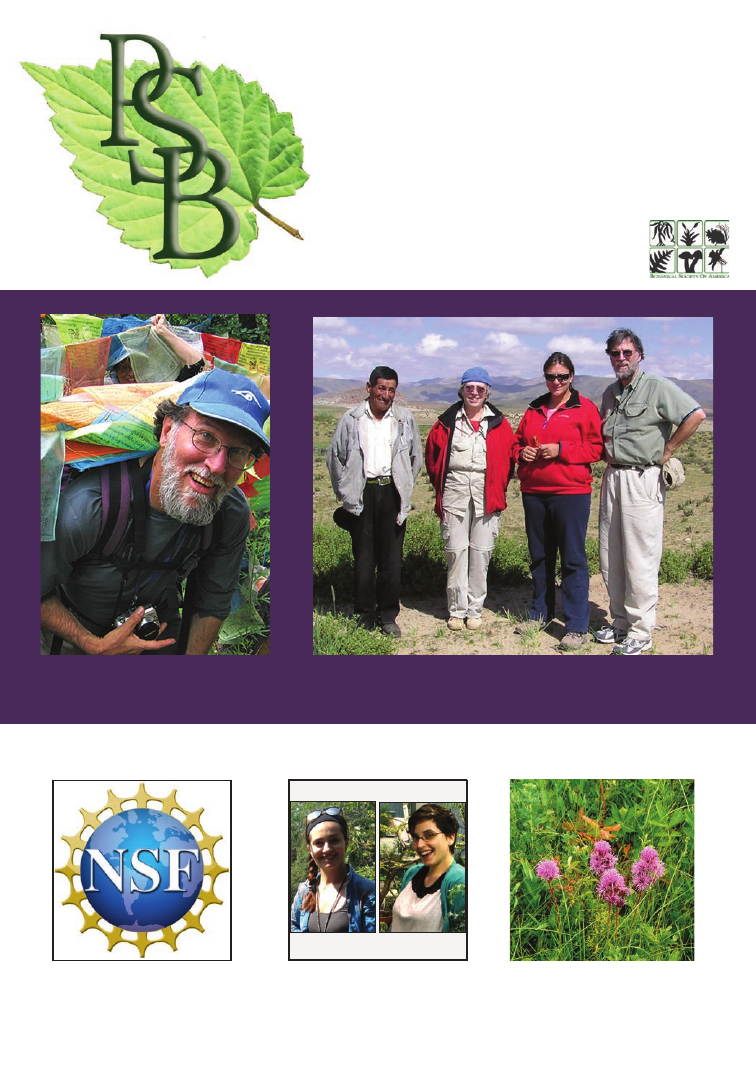

Figure 1. Dick Olmstead with Pedro Estra-

da, María Múlgura, and Alejandrina Alaria in

Jujuy, Argentina.

University of Washington – Sichuan

University Undergraduate Exchange

in Environmental Sciences

With support from the NSF and the Univer-

sity of Washington, in 2000, we initiated an

exchange program for undergraduates in the

environmental sciences. Involving students in

research was central to this program. Today,

nearly 500 students have participated in the

exchange. My active participation was only in

the first few years, during which time a bota-

nist also was active on the Sichuan University

side.

Two students stand out in my mind from

among many who have gone on to profession-

al careers in science. Yuan Yao-Wu was among

the first cohort of Chinese students to enter

the program (Figure 2). After spending his ex-

change year working in my lab in Seattle, he

returned to China to complete his senior the-

sis at the Institute of Botany in Beijing before

coming back to the University of Washington

for his Ph.D. (the first of many in that cohort

to complete a Ph.D.). Yuan was an invited

speaker in the BSA Presidents’ symposium at

Botany 2013 and is now Assistant Professor at

the University of Connecticut.

Figure 2. Yuan Yao-Wu in Sichuan, China

(2002).

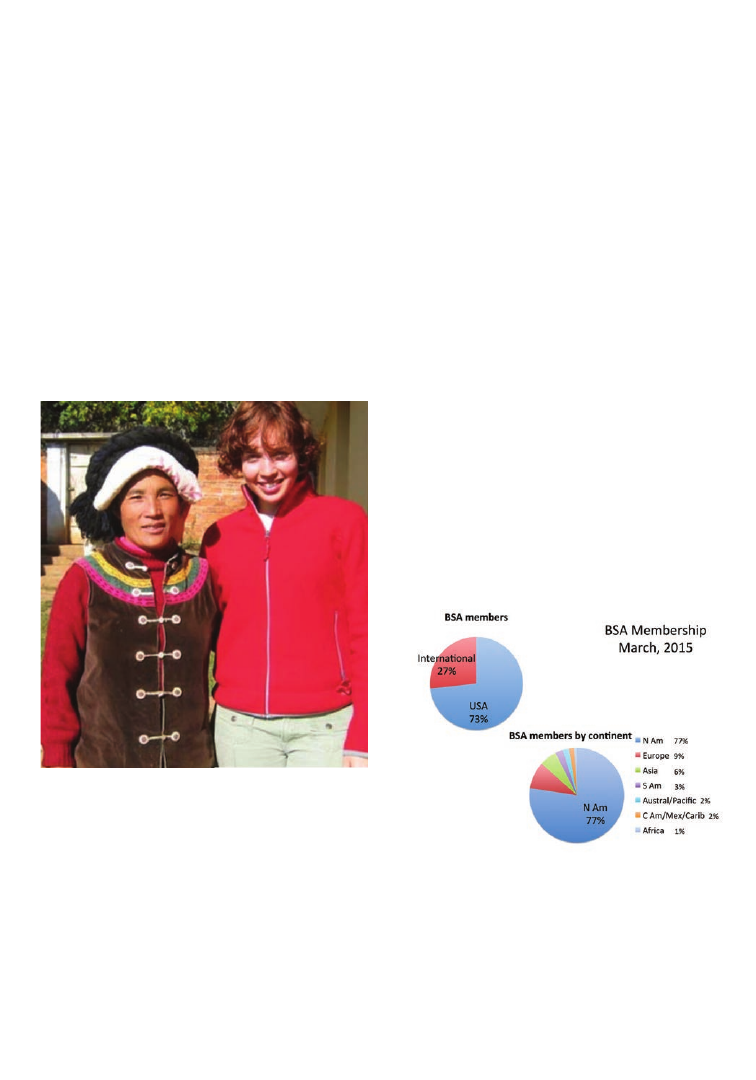

Rachel Meyer was in the second cohort of

UW students to study in Sichuan and partici-

pated in a student-led ethnobotanical study of

the ethnic minority Nuosu people in a remote

village in southern Sichuan (Figure 3). She

returned to Seattle to participate in research

in my lab before completing a Ph.D. degree at

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

122

the New York Botanical Garden on the origin

of domestication of eggplant. As a grad stu-

dent, Rachel was a student representative on

the BSA Board of Directors. She continued

research on the genetics of domestication as a

postdoc and is now an AAAS Fellow working

as an intern at the National Science Founda-

tion. Both Yao-Wu and Rachel attribute their

choice of career track and initial successes

to the opportunities made available to them

through this international exchange program.

For both of them, participation in, and sup-

port from, the BSA also helped launch their

careers.

Figure 3. Rachel Meyer with Nuoso woman in

Sichuan, China (2003).

As I considered what mark I might be able

to make as President of the BSA, I wondered

how representative my experiences were

among BSA members and if there was any-

thing the Society could do to advance interna-

tional collaboration in science and education.

In an effort to quantify this, with the help of

Membership Director Heather Cacanindin,

I asked members to fill out short, five-ques-

tion surveys about their experiences with in-

ternational collaboration. With background

information from the membership directory,

I devised three questionnaires: one for pro-

fessional botanists living in the United States,

one for students, and one for international

members. The surveys also provided an op-

portunity for members to comment individ-

ually. I will present the results of the surveys

here and have forwarded the results, along

with the many comments, to the BSA Com-

mittee on International Affairs.

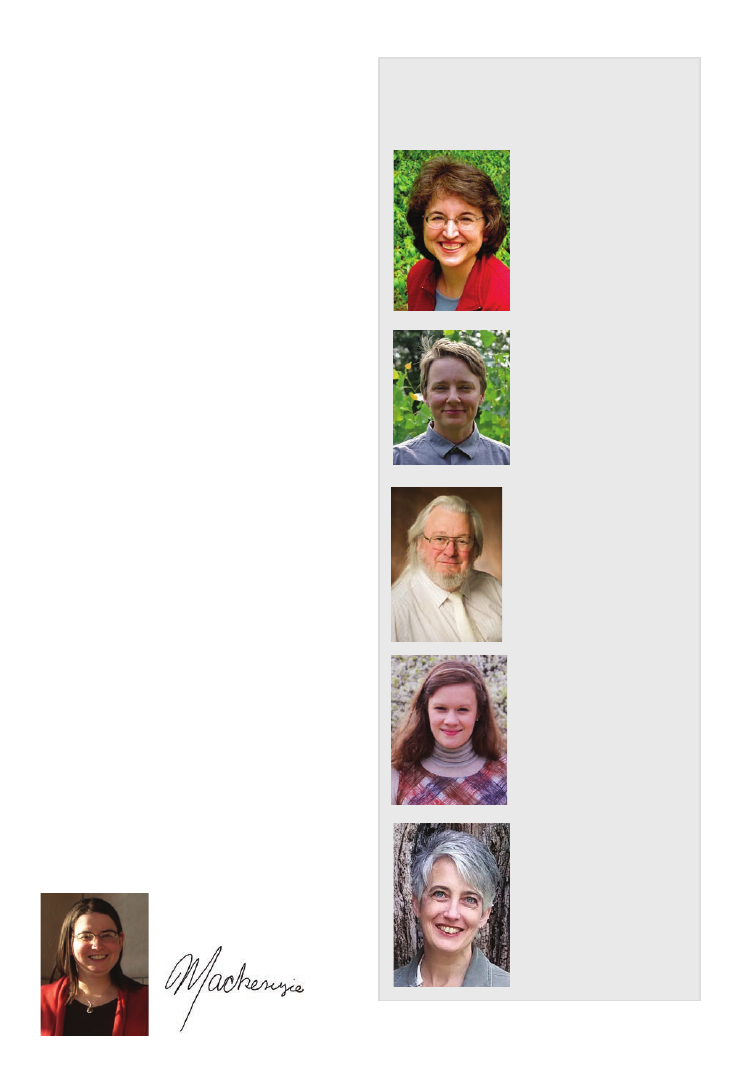

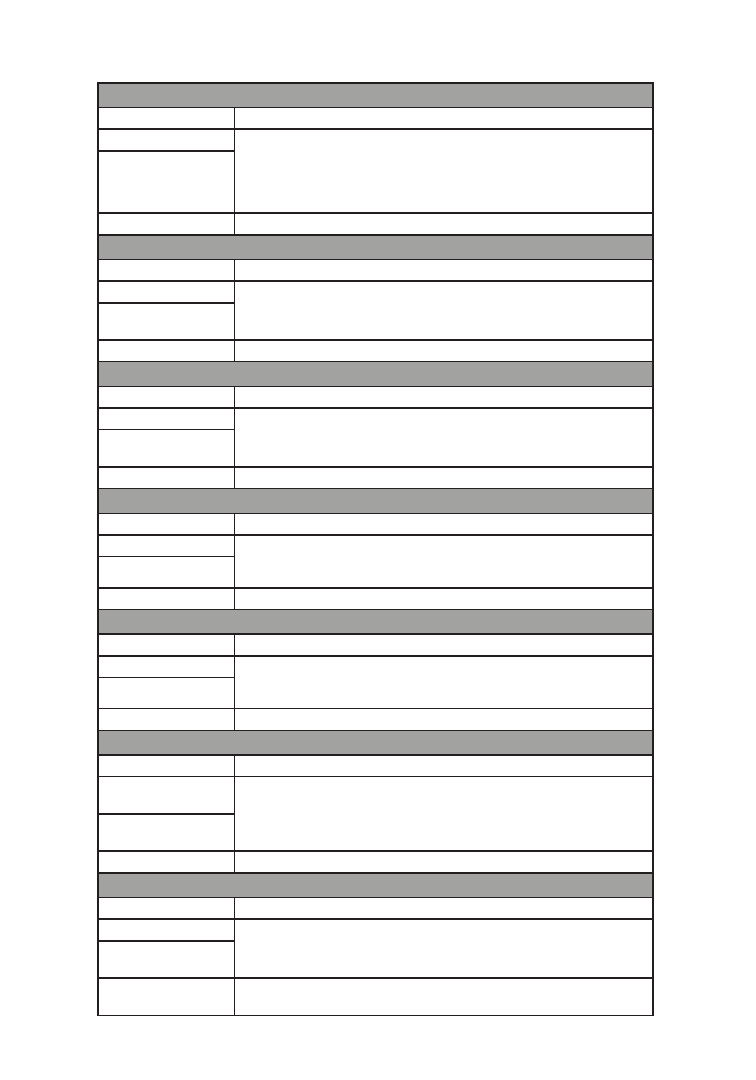

For a little background, I sorted the mem-

bership lists to see what our international

membership looks like. While our member-

ship base is still mostly from the U.S., 27% of

our members are from other countries. Our

neighbors to the north [Canada] account

for another 4%, leaving 23% from outside of

North America (Figure 4). Most of the re-

maining are from Europe, Asia, and South

America.

Figure 4. BSA international membership.

A total of 234 BSA members answered the

survey, including 152 U.S. professionals, 48

foreign members, and 34 students. In each

survey, most questions asked about interac-

tions that had occurred in the last few years

(2012-2015), in order to keep the answers

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

123

from respondents of different ages compa-

rable. Bear in mind that, while many mem-

bers responded, this is not a scientific survey

and there may be biases inherent in whether

members responded or not and in how they

interpreted the questions.

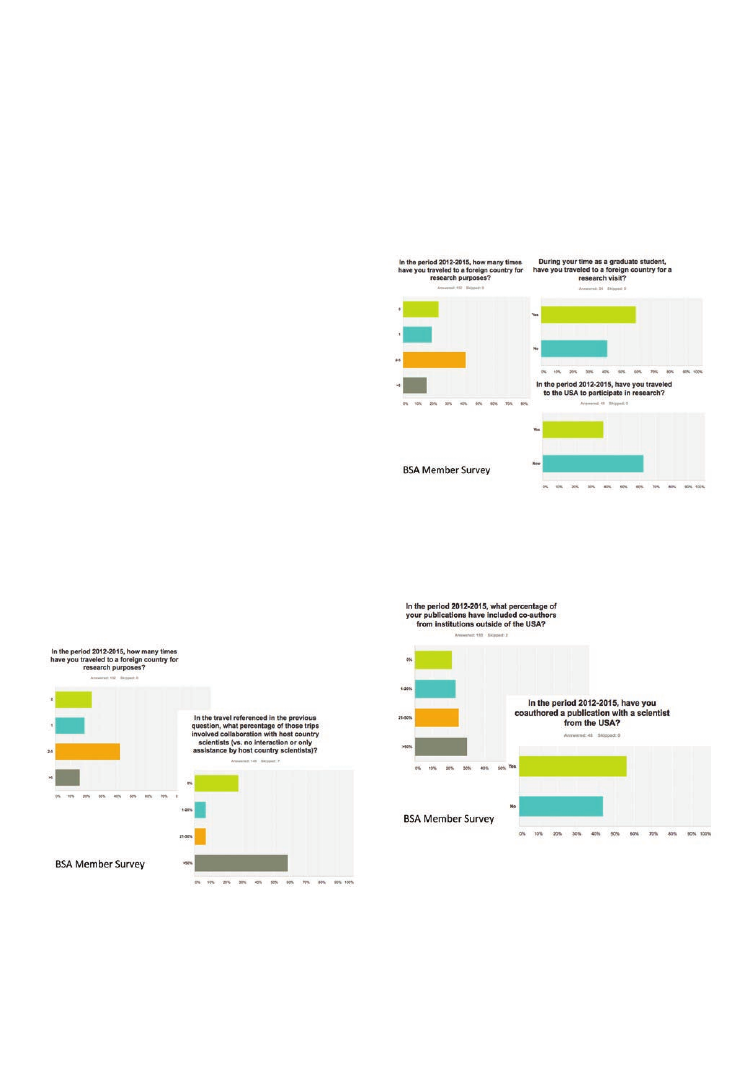

The first questions in each survey asked about

frequency of travel. Over 75% of professional

members from the U.S. had traveled to a for-

eign country for research purposes in that in-

terval, with a mode of two to five trips in the

designated time period (Figure 5). Of those

trips, approximately 75% involved collabo-

ration with host country scientists. In con-

trast, fewer than 40% of foreign members had

traveled to the U.S. to participate in research

(Figure 6). Nearly 60% of our student mem-

bers had traveled to a foreign country for a

research visit. I am impressed with the level

of international collaboration among society

members in the U.S., but perhaps we could do

more to encourage our foreign members to

visit our labs as part of our international col-

laborations.

Figure 5. International collaboration of BSA

members as measured by the number of times trav-

eled to a foreign country for research purposes (0, 1,

2-5, or >5) and the percentage of trips that involved

collaboration with scientists from the host country

(0%, 1-20%, 21-50%, >50%).

Our U.S. professional members also actively

engage foreign collaborators in their research

publications, with nearly 80% publishing with

co-authors from outside the U.S. during the

last 3 years (Figure 7). Nearly one third of

these members shared authorship with for-

eign scientists on half or more of their papers!

Figure 6. BSA members’ collaborative travel

history.

Figure 7. BSA members’ collaborative publica-

tions publications measured by the percentage

of publications with international co-authors

(0%, 1-20%, 21-50% or >50%) and occurrence

of international co-authors (yes or no).

Slightly over half of our foreign members have

published with scientists from the U.S. during

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

124

that same interval. One of the frequent com-

ments from foreign members was that they

joined the BSA to take advantage of oppor-

tunities for collaboration with scientists in

the U.S. However, in response to the survey,

over 60% of foreign members said that BSA

membership has not helped them to become

involved in international collaboration (Fig-

ure 8). I believe the BSA can do more to foster

these interactions

.

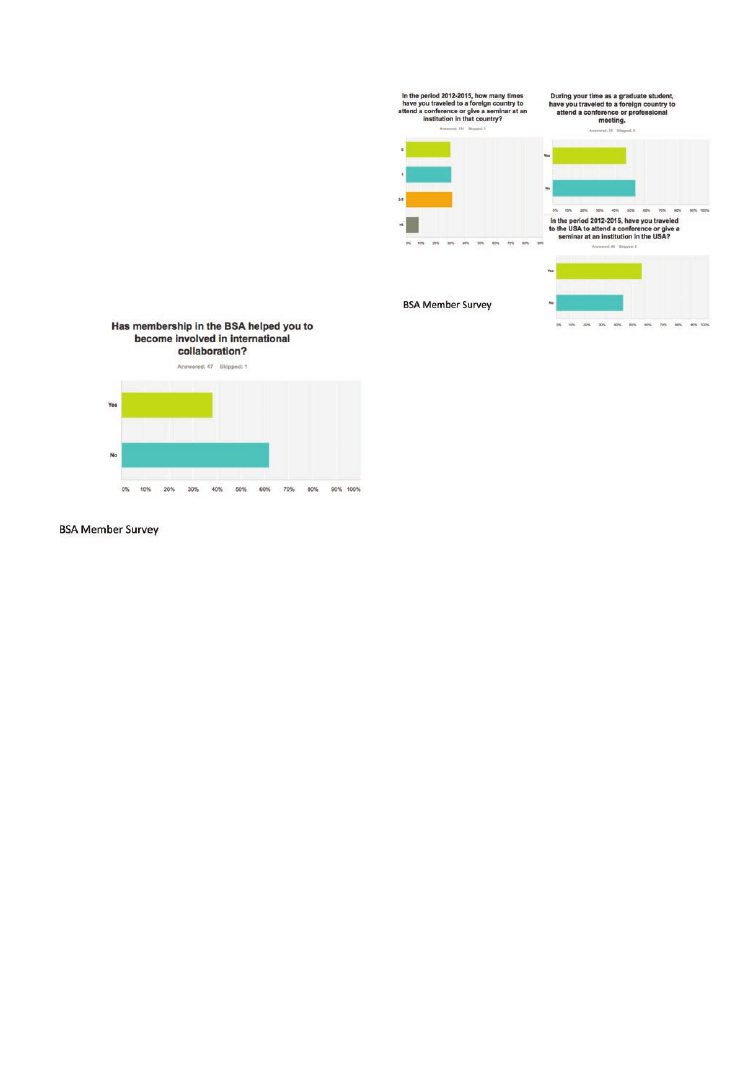

With many members thinking about attending

the International Botanical Congress (2017 in

Shenzhen, China), I was interested in mem-

bers’ participation in international confer-

ences outside of the U.S. Approximately 70%

of U.S. professional members have attended

one or more international conferences in the

past 3 years and more than half of foreign

members have traveled to the U.S. to attend a

conference during that time (Figure 9). I was

impressed to see that nearly half of our stu-

dent members had attended a conference in

a foreign country during their time as a grad

student.

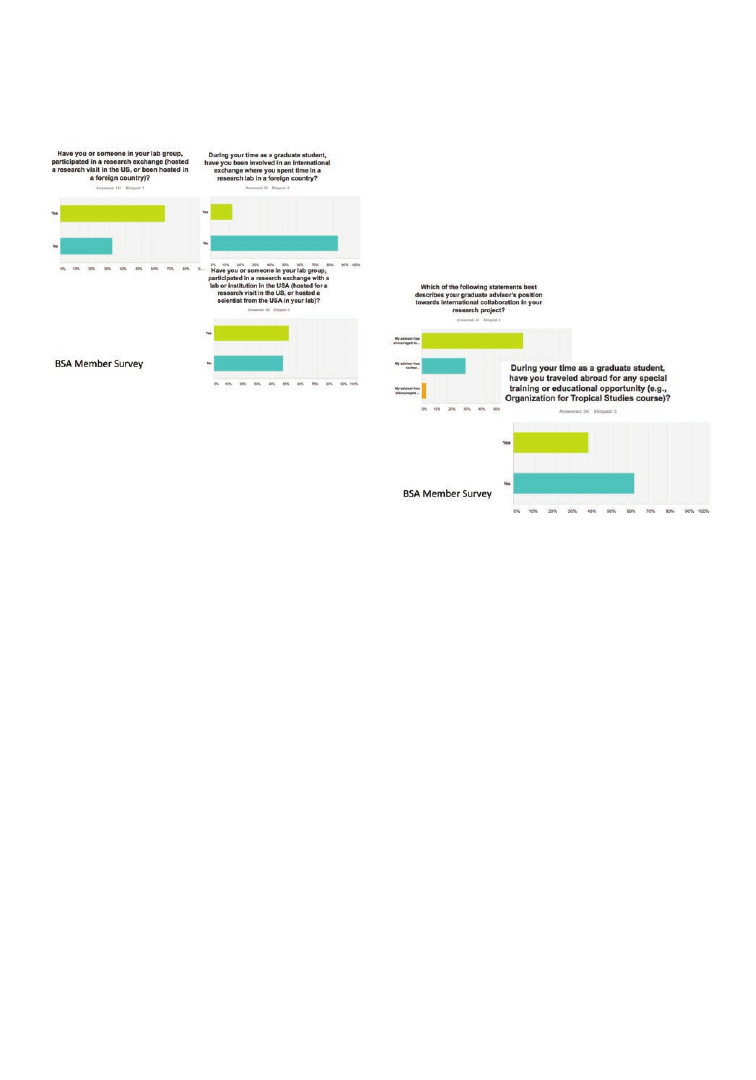

The value of international research exchang-

es is undeniable. A brief visit can be valuable

Figure 9. International travel to conferences by

BSA members including times traveled (0, 1,

2-5, >5) and occurrence of travel by U.S. profes-

sional members and foreign members (yes or no).

for establishing contacts and emerging collab-

orations, but having time to work together is

often essential for collaborations to fully de-

velop. In our survey, nearly two thirds of all

U.S. professionals report that they, or some-

one in their lab, has participated in a research

exchange, either hosting a foreign scientist or

being hosted in a foreign institution (Figure

10). More than half of international members

report participation in similar exchange with

a U.S. institution. Unfortunately, fewer than

15% of our students have had that opportunity.

Having the opportunity for international col-

laboration is a particularly valuable part of

graduate student development. There is no

better way to understand the impact of inter-

national collaboration than to experience it

oneself. I was pleased by the response to the

student survey to learn that two thirds of the

respondents have been encouraged by their

advisors to take advantage of opportunities

for international collaboration (Figure 11). In

addition to research exchanges, opportunities

for foreign travel for special training or educa-

tional opportunities are available for students

(e.g., Organization for Tropical Studies cours-

Society News

Figure 8. BSA membership’s ability to help in

international collaboration.

PSB 61 (4) 2015

125

es). Nearly 40% of student respondents have

taken advantage of such opportunities.

Figure 10. BSA members’ experience with re-

search exchanges, including participation of U.S

professional members (yes or no), graduate stu-

dents (yes or no) and foreign members (yes or no).

Increasingly, science is an international en-

terprise in which the network of connections

throughout the world can, if we choose to take

advantage of it, enhance everything that we

do as individual scientists. International col-

laboration in science and education seemed

to come naturally to me, but I realize that not

everyone has had the same opportunities that

I have had or has been encouraged to take ad-

vantage of them when they do occur. This is

where I think there is a role that the BSA can

play to help promote and facilitate interna-

tional cooperation in research and education.

What can the BSA do? In keeping with the

rapid globalization of botanical research,

the Society should do more to embrace a

leadership role in botanical research and

education worldwide. I think there are-

several things we can do to achieve this:

• Actively grow our international membership

• Partner with botanical societies in other

countries

• Provide a clearinghouse for information on

opportunities in research and education

• Promote international exchange and training

programs for students

• Facilitate contacts among botanists with

common interests

• Encourage member participation in interna-

tional conferences

I was struck by the survey comments from

international members indicating that they

hoped membership in the BSA would lead to

research connections, but also by the results

that show membership has fostered such col-

laboration for relatively few of them. If we can

help our members to connect and build their

own international networks, we can make a

difference in our science and in the careers of

those who practice it.

Reflecting back on that long microbus ride in

the Peruvian Andes, I realize that the personal

friendships I have made and the connection

to places and their histories have created em-

pathy for the issues confronting countries and

cultures around the world. The experiences

have not just made me a better international

botanist, but a better international citizen.

Society News

Figure 11. BSA members’ levels of encourage-

ment for international collaborations.

PSB 61 (4) 2015

126

Public Policy Notes

The BSA Public Policy

Quarterly

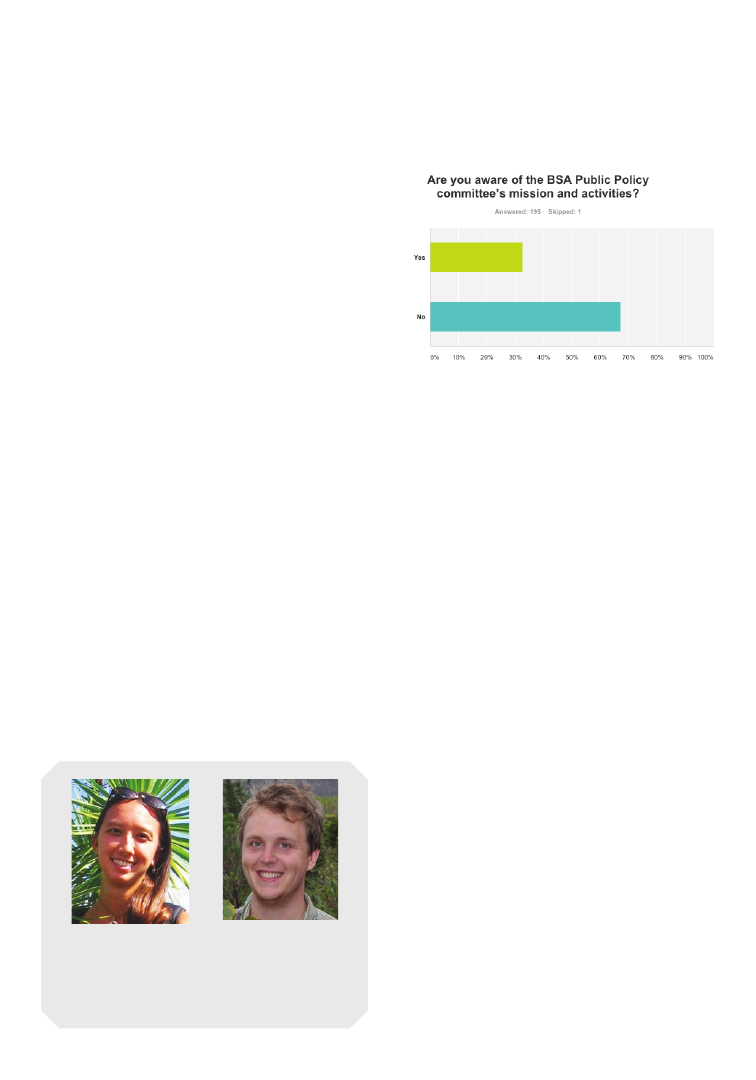

T

his year the BSA Public Policy Commit-

tee has been hard at work trying to bring

policy awareness and engagement to the BSA

membership. We surveyed members of the

BSA during Spring 2015 to understand how to

better provide our membership with the pol-

icy updates they need. We received responses

from 195 BSA members!

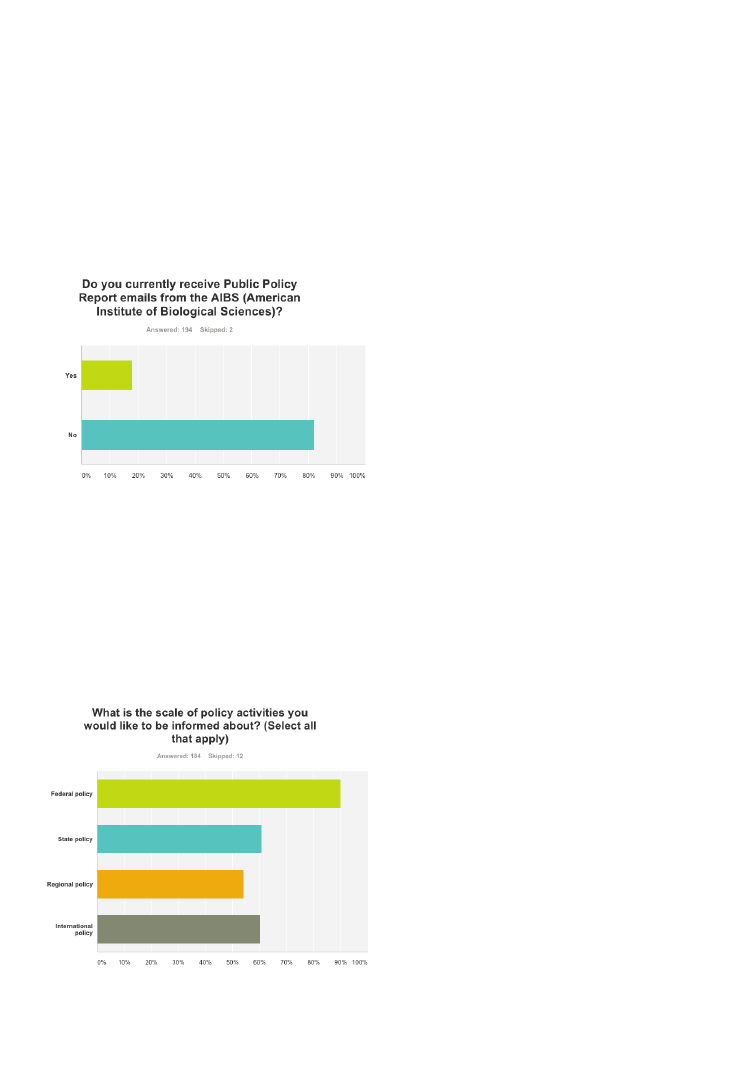

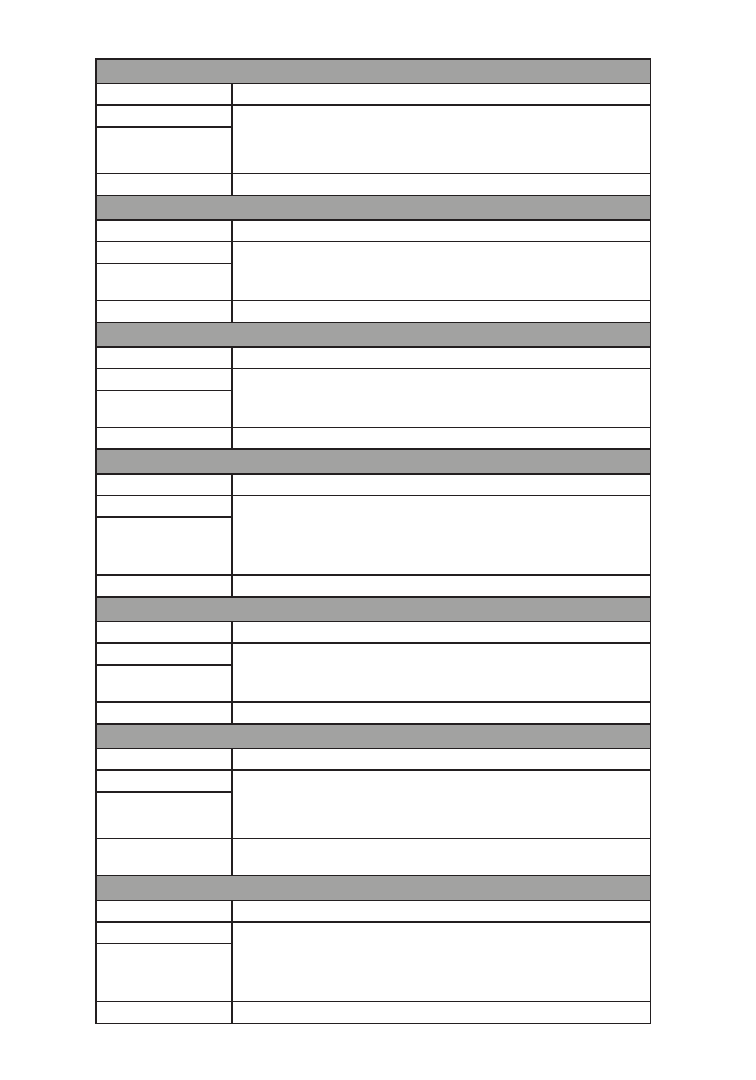

As a result, we found that a majority of you

want to be more involved in Public Policy, but

are unsure what our committee does and/or

how to become more engaged (Figure 1). As

a follow-up to your survey responses, we’ve

summarized our findings in this edition of the

Plant Science Bulletin. Here, we provide infor-

mation about the Public Policy Committee,

how to become more involved, and a sneak

peek at upcoming changes we have proposed,

including a new funding opportunity!

As for all BSA committees, the mission of the

BSA Public Policy Committee is outlined un-

der section XII of the society policies. The

Figure 1. Awareness of the BSA Public Policy

Committee.

Public Policy Committee is broadly defined,

but generally charged with “addressing is-

sues… to effect change, educate and influence

decision makers, and provide input from the

BSA perspective on public policy documents,

strategic plan documents from federal agen-

cies, and reports requesting input from plant

biologists.“ We work closely with other soci-

eties regarding policy, advise the BSA Board,

encourage members to present botany to the

public (including legislators and the general

public), and provide policy impact resources

for new activities to the BSA Board.

In order to make our impact more visible to

membership, we have taken the results from

our survey to heart and correspondingly up-

dated our activities.

How Often Would You Like to Be

Informed About BSA Public Polic

Activities?

A majority of you indicated that you would

like to be contacted either monthly (35%) or

quarterly (45%) regarding updates from the

Public Policy Committee, and we’d like to ex-

By Marian Chau (Lyon Arboretum Universi-

ty of Hawai‘i at Manoa) and Morgan Gostel

(George Mason University),

Public Policy Committee Co-Chairs

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

127

plain how to get the best of both worlds: by

reading this quarterly column in the PSB and

signing up for bimonthly AIBS Public Policy

Reports at http://www.aibs.org/public-poli-

cy-reports/ (Figure 2)! The BSA Public Policy

Committee works closely with AIBS and, as a

result, our policy actions are often linked to

updates in the AIBS reports.

Figure 2. BSA members receiving AIBS updates.

In addition to the survey results we’ve pre-

sented here, we received a huge number of

recommendations from members regarding

activities we can pursue, and we’re working

on bringing more things into the fold as we

speak (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Policy activities of interest to BSA

members.

Do You Have Any

Recommendations for BSA Public

Policy Committee Activities?

Your top five responses included:

• Federal funding for basic botanical re-

search

• Cultivate ties with other groups

• Promote botany through STEM education

• Threatened and endangered species listing

and conservation

• Loss of university botany departments and/or

herbaria

In response to these comments, some projects

that are in progress include developing a Policy

website, helping to draft collaborative work with

other groups to inform conservation legislation

that will go up for a vote in Congress, showcas-

ing Public Policy activities from our member-

ship, and the introduction of a new public policy

award.

We received contact information from 20 BSA

members (>10% of respondents!), and we are

contacting these individuals for Public Policy

Quarterly guest columns to showcase their

policy activities. If you are interested in pre-

paring a guest column, please contact us (see

below)!

In the meantime, be sure to apply for the

fourth annual BSA Public Policy Award to at-

tend Congressional Visits Day in Washington,

DC (include link when the application form is

complete), due January 25, 2016!

As always, we welcome any news, ques-

tions, or information regarding public pol-

icy news in botany. Please contact either

Marian (mmchau@hawaii.edu) or Morgan

(gostelm@gmail.com).

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

128

Economic Botany Notes

Extended Economic Botany

Avenues at the BSA

E

conomic botany is a broadening section

of the BSA, encompassing a myriad of

disciplines, and often providing an important

link between basic and applied research. At

this year’s Botany conference in Edmonton,

the Economic Botany section co-sponsored*

a well-attended multidisciplinary sympo-

sium, “Underutilized Crops for Secure and

Green Futures,” organized by section mem-

bers Nyree Zerega, Rachel Meyer, and Allison

Miller. Along with ten section talks and six

posters, the presenters explained the utility

of botanical resources to improve livelihoods,

serve as innovation platforms, impact ecology,

and recast our understanding of humans that

may all influence policy or genetic resource

development.

Following an introduction by Dr. Zerega high-

lighting the importance of underutilized crops

as an important—but largely untapped—

*

Support of the symposium was given by North-

western University, ASPT/BSA Systematics Section,

and BSA Genetics, Tropical Biology, and Economic

Botany sections.

source of plant genetic resources and the need

for more basic research on these species, at-

tendees heard six talks spanning the range

of disciplines represented by the BSA. Ear-

ly morning talks covered a study combining

forest ecology with ethnobotany to investigate

the impact of pre-Columbian management on

ecosystems, an analysis of the increasing ho-

mogeneity of the global food supply and pro-

posals for increasing crop diversity and food

security, and an investigation into crop wild

relatives at the intersection of economic bota-

ny, plant breeding, and systematics.

Late-morning talks included phylogenomics

and pollination biology of an underutilized

tree crop genus with a discussion of how ba-

sic research can be leveraged to promote the

development of underutilized crops, an over-

view of the African Orphan Crops Consor-

tium and the ambitious collaboration aiming

to develop genomic resources for 100 crops

and train African crop breeders to use them,

and finally an exploration of local adaptation

in amaranths, which contain both underuti-

lized crops and weeds, using phylogenetic and

population genomic tools.

Section posters ranged from showcasing ap-

pealing traditional plant uses for health and

for food packaging [Nepenthes can be a wrap-

per for sticky rice! (Schwallier et al.)] to tem-

perature tolerance phenotyping of crops and

phytochemical medicinal activity. Oral pre-

sentations included developmental, nutrition-

al, and ecological impact analyses of new and

underutilized foods and fodders. Fieldwork

and collection analyses of rice and chickpea

helped to reset ideas of adaptation trends.

By Elliot Gardner (Northwestern University

and Chicago Botanic Garden) and Rachel S.

Meyer (New York University)

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

129

New morphometric methods enabled infer-

ence of functional diversity. Geospatial collec-

tion assessment was used to set priority col-

lection areas for major crops. Extensive tribal

ethnobotanical databases were compared to

assess completeness.

Although the Economic Botany section is

small, its scope is great, bringing together re-

searchers from a wide variety of disciplines—

including systematics, genomics, phyto-

chemistry, ecology, ethnobotany, population

genetics, and policy—united by the study of

economically important plants. To address

the growing need to connect our section with

various disciplines and agencies, we have cre-

ated a new Community Relations Officer. We

have kept our section dues flat to encourage

broad participation in our section. We also

encourage students doing multiple- or in-

ter-disciplinary science to apply for Economic

Botany section travel awards and present at

the next meeting.

For more information, please contact either

Elliot (egardner@u.northwestern.edu) or

Rachel (rm181@nyu.edu).

References

Schwallier, Rachel, et al. 2015. Traps as treats: a tradi-

tional sticky rice snack persisting in rapidly changing

Asian kitchens. Poster from Botany 2015. http://2015.

botanyconference.org/engine/search/index.php?-

func=detail&aid=70.

Society News

PSB 61 (4) 2015

130

Upcoming Award Deadlines

February 1st

• BSA Awards - General

• Darbaker Prize

• BSA Public Policy Award

March 1st

• BSA Student Travel Awards

• PLANTS Grants

March 15th

BSA Awards - General

• Distinguished Fellow of the Botanical Society

of America

• BSA Emerging Leader Award

• Charles Edwin Bessey Teaching Award

• BSA Corresponding Members

• Grady L. Webster Structural Botany Publica-

tion Award

• BSA Awards - Students

• BSA Young Botanist Awards

• BSA Graduate Student Research Awards

• BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards

• Genetics Section Graduate Student Research

Awards

April 1st

• BSA Awards - General

• Jeanette Siron Pelton Award

April 10th

• Pteridological Section & American Fern So-

ciety Student Travel Awards

• TRIARCH “Botanical Images” Student Travel

Award

• Vernon I. Cheadle Student Travel Awards |

Developmental & Structural Section Student

Travel Awards

• Ecological Section Student Travel Awards

Economic Botany Section Student Travel

Award

• Genetics Section Student Travel Awards

The BSA has entered the awards season! Please visit http://botany.org/home/awards.html

for further information about the following awards as well as more information about BSA awards.

Society News

131

ARTICLES

Information about NSF Programs,

Policies, and Proposals:

What, Where, Why, How?

T

he scientific community always has

many questions about the Nation-

al Science Foundation (NSF); its programs,

funding applications, and proposal and re-

view process; and how things work in gen-

eral. While these items are covered in vari-

ous places on the NSF website (http://www.

nsf.gov), finding them can be challenging,

and searching requires some knowledge of

what terms to use. The NSF website is con-

stantly being updated and new functions

often appear to help you in your searches.

To keep researchers informed, NSF offers

“NSF Days” (http://www.nsf.gov/about/

congress/nsfdays/index.jsp) in various sites

around the country each year. In addition,

Program Directors (or Program Officers as

used in the Proposal and Award Policies and

Procedures Guide [PAPPG]) provide infor-

mation sessions at many professional society

meetings, as did the three authors at Botany

2015. We hope this short orientation based on

our information session this past July will help

researchers obtain the information they need

more easily.

About NSF (The “What”)

The NSF is a federal agency, and as such, its

budget and many of the priorities for the

agency are determined by the U.S. Congress,

the Office of Science and Technology Policy

(OSTP), and the President’s budget request

through the Office of Management and Bud-

get (OMB). For the most part, the distribution

of budget funds within NSF has been deter-

mined by the NSF Director’s Office and senior

management (Assistant Directors who are

the heads of the various Directorates at NSF).

They discuss the various policies and priorities

to be addressed with funding streams, but in

recent times, the U.S. Congress has put some

limitations on how funds are to be distributed

inside NSF. For example, Congress has deter-

mined funds for the Major Research Instru-

mentation Program. You can find the NSF

By Judith E. Skog

Sedimentary Geology and Paleobiology,

Earth Systems GEO

Roland P. Roberts

Biological Infrastructure, BIO

Joe T. Miller

Environmental Biology, BIO

National Science Foundation, Arlington, VA

PSB 61 (4) 2015

132

budget requests and final budgets at http://nsf.

gov/about/budget/.

We point this out because program directors

typically are not the ones determining where

resources go, so arguing your case for spend-

ing priorities at their level might not be the

place to direct this issue. If a program director

notes that he or she can’t make this decision,

please believe him or her! It should also be

noted that OSTP will often form Interagency

Working Groups to address issues that span

government agencies (one was formed on

plant genome issues and one was addressing

Scientific Collections). At times, the response

to these working group findings could be new

programs or initiatives at NSF (e.g., the Plant

Genome Research Program and the Advanc-

ing Digitization of Biological Collections pro-

gram). In addition, the National Academy of

Sciences (NAS) often forms special commit-

tees to examine research issues, or the sci-

entific community will hold workshops that

result in reports on special areas of research

needing attention. NSF may use these reports

It is also important to understand that NSF

is overseen by the National Science Board

(NSB), and that body determines policies for

NSF. The NSB, for example, recently released a

report on reducing the workload for Principal

Investigators (http://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2014/

nsb1418/nsb1418.pdf) in which preliminary

proposals were recommended as a mechanism

that should be tested. The “About NSF” web

page (http://www.nsf.gov/about/) provides a

lot of information, including NSF’s current

priorities, strategic plan, and the composition

of the NSB. Being familiar with these items

can help you understand the goals of many of

the programs within NSF and to whom you

should address concerns about opportunities

for support.

Science and engineering research and educa-

tion support at NSF is organized into seven

directorates under the Office of the Director:

• Biological Sciences

• Geosciences

• Computer and Information Science and

Engineering

• Engineering

• Social, Behavioral and Economic Science

• Education and Human Resources

• Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

Within directorates, organization varies;

some are divided further into divisions, clus-

ters or sections, offices, virtual activities, spe-

cial activities, or other units that make sense

for their size and activities. This structure may

seem to be narrowly divided; however, there is

opportunity for exchange of ideas, co-review-

ing, and collaboration among the entities.

Be assured, the scientists working at NSF rec-

ognize the collaborative nature of research

and strive to provide the best reviews of the

science within each program and across what

may appear to be a restrictive and narrow

focus of the various programs. We note this

Researchers often think

they can only look to

their “home director-

ate” for support, but it

is important for every-

one to peruse programs

across NSF.

as priorities for the foundation are consid-

ered. Many professional societies (e.g. AIBS,

AAAS, as well as BSA) have public policy of-

fices or committees, and they can be valuable

resources to help one understand how the sci-

ence funding policies are determined.

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

133

because researchers often think they can only

look to their “home directorate” for support,

but it is important for everyone to peruse

programs across the foundation. For exam-

ple, the Major Research Instrumentation pro-

gram is managed through the Office for In-

tegrative Activities (http://www.nsf.gov/dir/

index.jsp?org=OIA) under the Office of the

Director, and some international activities are

supported through the Office of Internation-

al Science and Engineering (http://www.nsf.

gov/div/index.jsp?div=OISE).

Although the science is overseen by the var-

ious directorates/programs, the actual finan-

cial part is overseen by the Office of Budget,

Finance, and Award Management. The di-

vision of this office you will most likely deal

with is the Division of Grants and Agreements

(DGA), since DGA actually makes the awards

recommended by the science divisions. Your

sponsored research office (SRO) is probably in

close contact with DGA and its policies, and

you should consult your SRO about budget is-

sues when preparing proposals or you should

consult your grants officer if you have ques-

tions about an award. Program directors will

answer questions about the science for pro-

posals and awards.

A program director will typically be your pri-

mary point of contact at NSF, and it is worth-

while to know there are various ways program

directors are employed at NSF. There are pro-

gram directors who are permanent employees

whose only job is at NSF. Then there are cat-

egories of temporary staff who serve shorter

terms at NSF. Rotating program directors may

come for 1 to 3 years through (1) the Intergov-

ernmental Personnel Act (IPA), where these

people retain their institution employment

and NSF pays the institution for their services,

(2) Visiting Scientists who take leave from

their university and are paid by NSF, and (3)

temporary federal employees who resign oth-

er jobs and are full time for a limit of 3 years

at NSF. There are also “experts” hired for spe-

cial tasks (e.g., to fill in short-term within pro-

grams on a part-time basis). Rotator positions

are an opportunity for others to learn more

about NSF and to bring their special scientific

expertise to the foundation. Announcements

appear regularly for these openings, and they

are posted on the NSF website on the director-

ates’ web pages and on USAJOBS.

Information on Programs

(The “Where”)

Most likely, many of you as plant biologists

will be considering funding opportunities

through programs managed by the Director-

ate for Biological Sciences (BIO, http://www.

nsf.gov/dir/index.jsp?org=BIO), so we will

provide a brief overview of this directorate.

There are four divisions in the directorate: Bi-

ological Infrastructure (DBI), Environmental

Biology (DEB), Integrative Organismal Sys-

tems (IOS), and Molecular and Cellular Biol-

ogy (MCB). As you can see, the divisions ad-

dress research at the level of the cell and below,

the organism level, above the organism level,

and any research or program that provides in-

frastructure required for biological research,

including education from undergraduate to

postdoctoral researchers.

A program director will

typically be your primary

point of contact at NSF,

and it is worthwhile to

know there are various

ways program directors

are employed at NSF.

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

134

We do not describe individual programs here,

because the goals, the criteria, and the em-

phasis can change from year to year. You can

find a list of upcoming funding opportunities

for BIO on nsf.gov (http://go.usa.gov/3WZsy)

and on the main BIO blog, BIO Buzz (https://

nsfbiobuzz.wordpress.com/programs/). You

should read the program description and so-

licitation that are the most recent versions be-

fore you begin work on any proposal. When a

solicitation has been replaced by a newer ver-

sion, there should be a note at the top of the

solicitation giving the newest number or not-

ing that it has been replaced. Be sure to check

for any indication of revision.

Some programs within BIO are collaborative

with other directorates or other agencies or

have other groups setting priorities. The Plant

Genome Research Program located in IOS,

for example, is developed based on plans pro-

duced every five years by a working group of

several governmental agencies (who were part

of the OSTP Interagency Working Group for

Plant Genomics mentioned above), and this

program’s priorities may change depending on

that plan. As another example, the BIO post-

doc program often partners with other direc-

torates to address a need for new researchers

to be trained as interdisciplinary scientists. If

there are no external partners in the postdoc

program, a group of program directors from

all the divisions within the BIO directorate

considers areas of need for new expertise in

a specific biological area of research and rec-

ommend this as an emphasis for the postdoc

program. These areas of emphasis generally

continue for five years.

Some additional items of note regarding BIO

programs: There are special programs that

have their own deadlines and requirements,

such as CAREER, OPUS, Genealogy of Life,

LTREB, Ecology of Infectious Diseases, Re-

search Coordination Networks, and Dimen-

sions of Biodiversity. These do not fall under

the same deadlines or requirements as the

core programs, even though they are funded

out of the same money as the core programs

(for a complete list of BIO active funding op-

portunities, visit http://www.nsf.gov/funding/

pgm_list.jsp?org=BIO&ord=date). Note that

DEB also has a small grant category that is

labeled at the preproposal stage as a project

whose budget is capped at 150K; this is for

projects that are smaller in scope and size.

So far, the funding rate for these DEB small

grants is slightly higher than for the rest of the

core grants. You can find further information

about small grants in the program solicitation

and information about the funding rates for

the small grants on the DEB blog (http://www.

nsf.gov/div/index.jsp?div=DEB).

Also remember that programs are not static

and the emphasis may change or there may

To gather additional infor-

mation and advice on BIO

programs, we recommend

you read the blogs from the

BIO divisions for analyses of

programs and funding rates,

news items about research,

statistics on awards, staff

profiles, and advice on vari-

ous programs:

• DEB blog (DEBrief):

http://

nsfdeb.wordpress.com

• IOS blog (IOS InFocus):

http://nsfiosinfocus.word-

press.com

• MCB blog:

https://nsfmcb.

wordpress.com/mcb-blog/

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

135

be programs with defined limits to their ex-

istence based on budgets or new government

emphases. Once a special program reaches

its set duration, the research may be includ-

ed within core programs, the special program

may be redefined, or additional buy-in from

across NSF or other agencies may continue

the program with a different format or em-

phasis.

To gather additional information and advice

on BIO programs, we recommend you read

the blogs from the BIO divisions. The division

blogs are where you can find analyses of pro-

grams and funding rates, news items about re-

search, statistics on awards, staff profiles, and

advice on various programs such as CAREER:

• DEB blog (DEBrief): http://nsfdeb.word-

press.com

• IOS blog (IOS InFocus): http://nsfiosinfocus.

wordpress.com

• MCB blog: https://nsfmcb.wordpress.com/

mcb-blog

/

While most botanists seek funding from the

BIO directorate, as we said above, you should

look for funding opportunities throughout the

foundation. If you are developing computer

informatics that are of general use, check out

programs under the Computer and Informa-

tion Science and Engineering (CISE) director-

ate (http://www.nsf.gov/dir/index.jsp?org=-

CISE). The Geosciences (GEO) directorate

(http://www.nsf.gov/dir/index.jsp?org=GEO)

also includes programs that could be useful to

consider; if you are doing research in the po-

lar regions, check out Polar Programs (http://

www.nsf.gov/div/index.jsp?div=PLR); or if

you are studying fossils, read about the Sed-

imentary Geology and Paleobiology program

(http://www.nsf.gov/div/index.jsp?div=EAR).

For Education activities, such as REU sites,

new undergraduate efforts, graduate student

programs and education research, the Educa-

tion and Human Resources (EHR) directorate

(http://www.nsf.gov/dir/index.jsp?org=EHR)

is the place to look. If you are unsure about

where your specific research fits best, use the

NSF awards database to search for keywords

that describe your research. You may discover

programs that you had not considered previ-

ously.

Process and Policies

(The “Why”)

Program Directors are often asked why cer-

tain programs have different requirements or

review methods (e.g., panels, ad hoc review-

ers, a combination of these two, or no reviews

for certain categories). We call your attention

to a document that was produced after a Mer-

it Review Working Group analyzed a number

of issues at NSF with respect to workload,

the burden on the community, and the bur-

den on Principal Investigators: http://www.

nsf.gov/oirm/bocomm/meetings/nov_2011/

Merit_review.pdf. In this document, there are

a number of charts and graphs illustrating the

merit review challenges occurring in the past

decade. Of particular interest will be the last

two pages (pp. 25-26) where numerous sug-

gestions are made for ways to improve the re-

view process. Several of these are being tested

across NSF to see if they are effective.

For example, programs within DBI and MCB

have a single deadline per year, whereas DEB

and IOS require preproposals and then those

investigators who are invited to do so may

submit full proposals. Some GEO programs

are testing, having no deadlines, with propos-

als being accepted anytime. Other programs

limit the number of proposals that may be

submitted by a PI in a given time frame. Be

sure to visit the various directorate and divi-

sion web pages and the program pages and

solicitations to understand the deadlines, the

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

136

goals and priorities, and the various required

documents for each program. You also need

to review carefully the PAPPG, which is the

general information source for policies and

procedures for all submissions to NSF in general.

Proposal Information

(The “How”)

Okay, you are now informed on how to tackle

programs and find the information you need

about them. Now we’ll discuss the proposal

process. Many good proposals are submitted

to programs, but what is a “good proposal”? A

good proposal is a good idea, well expressed,

with a clear indication of methods for pursu-

ing the idea, evaluating the findings, and mak-

ing them known to reviewers and others who

need to know.

However, just writing a good proposal does

not make it competitive within a particular

program. A competitive proposal is a good

proposal and it is appropriate for the program

and responsive to the specific requirements

of the program solicitation or announcement

(program summary). It also conveys some ex-

citement and innovation in the field of study;

therefore, you should always read and consid-

er all information about the program carefully

before you begin to write a proposal.

When reading a program summary and so-

licitation, focus on the goals of the program,

eligibility requirements, and other special

requirements and review criteria. Keep the

review criteria in mind as you think about

writing a proposal. Intellectual merit refers to

the ways in which the proposed activity will

advance science and engineering through re-

search and education. Broader impacts are the

broader scientific and societal impacts of the

project and its potential results. In addition

to these two overall criteria, look for special

review criteria for the program as described

in the announcement or solicitation. Often,

at the end of a solicitation, there is a section

called “Additional Review Criteria.” Be sure to

read solicitations thoroughly, as we find this

section is often missed. Every page of a solic-

itation provides important information for

preparing a competitive proposal. You may

want to ask someone for a copy of their suc-

cessful proposal—but remember that some

program announcements are reissued year-

ly or on a regular cycle, so the emphasis can

change. The award abstracts database (

http://

nsf.gov/awardsearch/

) is a good place to find

recently funded awards for a program to see

what the emphasis has been in recent years.

On the program web page, you will find a link

at the bottom for “Recent Awards in this Pro-

gram” that will quickly take you to the most

recent awards and save you from searching all

of the NSF awards database.

Identify your best research ideas for which you

have some preliminary data. Be sure you have

developed clear hypotheses and experimen-

tal procedures before you take the next steps.

Consider feasibility in a 36- to 60-month win-

dow and what assistance you will need, given

teaching and other time commitments. Think

carefully about the budget request and how

you would justify that request based on the

Often, at the end of a so-

licitation, there is a sec-

tion called “Additional

Review Criteria.” Be sure

to read solicitations thor-

oughly, as we find this

section is often missed.

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

137

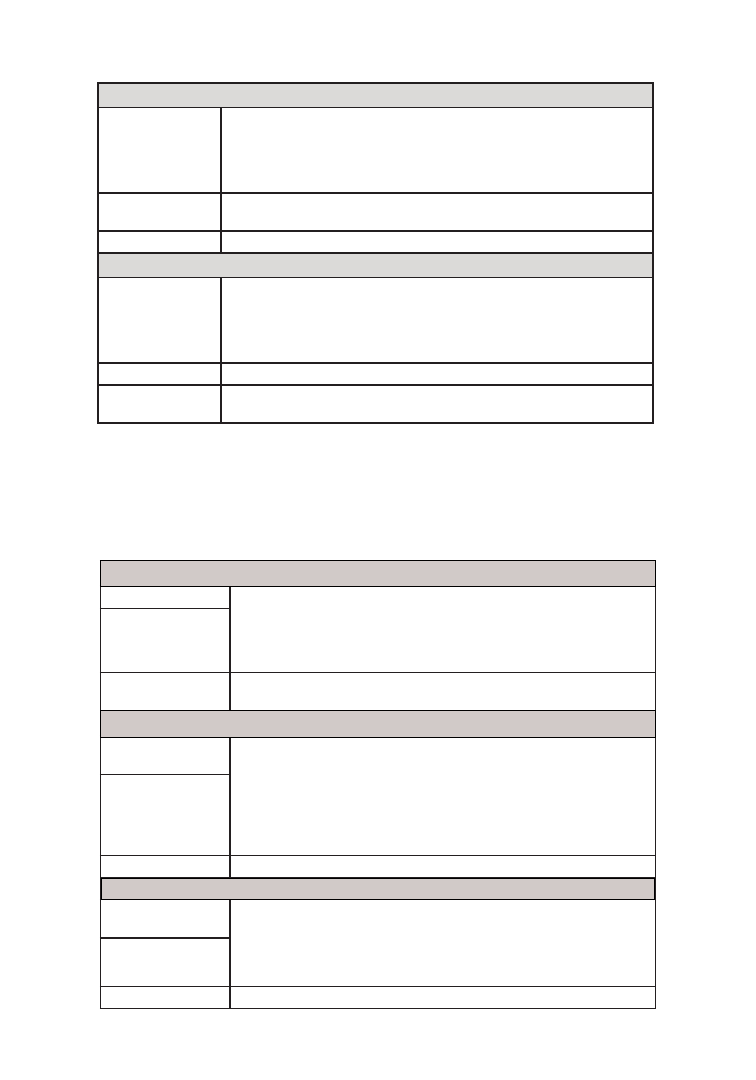

Commandments for a

Competitive NSF Proposal

• Thou shalt start early! Give yourself

enough time to check all the items and

consider the proposal for all the criteria.

Think carefully about the budget and that

it is well justified by the research program.

• Thou shalt address the NSF review cri-

teria thoroughly! Both intellectual mer-

it and broader impacts should be ad-

dressed and related to the project. This is

especially important when considering

the broader impacts, since there should

be some direct relevance for the research

in a societal context. To simply say you

will participate in an ongoing activity

at your institution is not enough; ex-

plain why your project is important for

that activity and why that activity is im-

portant for your project. Be as specific

about the broader impacts of the project

as you are about the intellectual merit.

• Thou shalt read the PAPPG and the pro-

gram announcement and solicitation!

Follow all instructions in these doc-

uments.

• Thou shalt get feedback on your proposal

from your colleagues! Proposals should

be cogent, appropriate, and justified.

Study the reviews carefully if you receive

them—for both awards and declines.

Anticipate criticisms and invite criticism

before you submit. Do not ask only the

people close to your field of research, but

ask someone who is not familiar with

what you are doing to provide comment.

If that person says something like “It was

OK,” don’t submit that proposal. If that

person says, “Wow, I had no idea your

work was so interesting,” send in the pro-

posal. Remember that when this project

is read in a panel, you will have at least

three people reading it and comparing it

to the other proposals within that pan-

el. If the two people who are outside the

specific area of your research don’t like it

because they don’t see the rationale or the

excitement of this research, their reviews

won’t be enthusiastic either. And you

need to convince a wide audience of peo-

ple that your work is important. Which

brings up the next commandment….

• Thou shalt not irritate the reviewers!

Be clear and concise and make it easy

for reviewers to understand all parts of

the project. Think like a reviewer be-

fore you submit the final draft. And, by

the way, do submit the final draft—not

the one with the comments inserted

into the text that say “This paragraph

needs work!” Yes, we have seen those.

• Finally, thou shalt contact your program

director! If questions remain about items

within the proposal, we are here to help.

We realize that not all the items in the doc-

uments we provide are clear to everyone,

and there are ways of interpreting pro-

gram announcements that require some

clarification. Don’t be afraid to write with

specific questions or to request a phone

conversation; it’s always best to prepare

your PD prior to a phone call. We can’t an-

ticipate all questions, and some answers

require a bit of research and discussion.

You will speed up the process by asking

the question or outlining the problem

and requesting time for a conversation if

the answer cannot be provided through

e-mail. Obviously, e-mail is preferred, so

we all have a record of the question and

the answer, and to maintain consistency

with decisions made within the program.

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

138

proposed activities. Communicate with a pro-

gram director who can assist in determining

the project’s relevance for the program and

answer your questions.

Writing a Proposal

Read the PAPPG (http://www.nsf.gov/pub-

lications/pub_summ.jsp?ods_key=papp) for

guidance and instructions on proposal prepa-

ration and submission, and all criteria for the

proposal to be accepted by the system. The

guide describes the process for declinations,

returns, withdrawals, awards, and significant

items for grant administration. The require-

ments in this guide apply to all proposals

submitted to NSF, but remember, there may

be additional requirements or more restric-

tive requirements found within a program’s

solicitation or announcement. So, when com-

posing your proposal, first follow the PAPPG

and then apply any changes or additional con-

tent described for the program solicitation to

which you are responding.

Anticipate some frustration along the way.

If your proposal is declined and the reviews

and panel summary do not make clear why,

first look to see if there is a program director

(“PO”) comment on your proposal. If not, or

if this still does not address your concerns,

contact the program director once you have

thought carefully about the reviews and the

questions they raise. If awarded, follow up on

reporting and stay in touch with the program

about your accomplishments and publica-

tions. NSF is always eager to share PI research

and education outcomes on their website and

via social media.

A Note about Preproposals

Does our advice apply to preproposals where

these are required? Mainly, yes. Programs will

provide instructions for preproposals in the

announcement and there will be information

about preproposal submission. Typically, sim-

ilar instructions are included for preproposals

and proposals; however, since preproposals

are shorter, it is important to understand what

makes a good preproposal. In a preproposal,

reviewers look for excitement, significance,

rationale for the main idea, and a justification

that the methods proposed will answer the

question posed. The conceptual framework of

the main objectives and the specific aims for

the project must be clearly stated. And, as with

full proposals, the broader impacts should be

relevant for the project.

Final Bit of Advice

Stay up to date on NSF programs, deadlines,

jobs, and events by subscribing to the NSF

news feed, which you can find under the News

web page (http://www.nsf.gov/news/). At the

top of the page is a link to receive news by

email. When you subscribe, you can choose

how to receive news items, how often, and

which items you want to receive so you will

not be flooded with information not relevant

to you. In addition, you may want to read

the BIO blogs and follow NSF and BIO on

Twitter and Facebook (see http://www.nsf.

gov/social/). Being informed about critical

dates, changes in programs, new programs, or

changes in requirements or policies is the best

way to prepare and submit proposals that are

appropriate for a program at NSF.

Articles

PSB 61 (4) 2015

Articles

139

Nisku Prairie: An Aspen Parkland

Remnant in Central Alberta,

Canada: Conservation Challenges

by Patsy Cotterill

Cotterill is an Edmonton botanist. She is a

steward of three protected areas in the aspen

parkland and boreal regions of Alberta,

Canada, and also volunteers with City of

Edmonton natural areas and parks.

I

n the Interior Plains of North America, as-

pen parkland extends as an arc some 200 to

250 km wide from the foothills of the Rocky

Mountains across the Canadian Provinces of

Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. It is a

vegetation zone unique both to North Amer-

ica and the world, bounded in Alberta by the

boreal forest to the north and the grasslands

region to the south. It is so named because

it naturally consists of a mosaic of groves of

trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) and

open grassland, dotted with wetlands in

low-lying areas. Its flat or undulating topog-

raphy is a legacy of glacial debris deposited at

the end of the last glaciation; silt from glacial

lakes, till from in situ glacier melting, wind-

blown sand dunes or glacial outwash from

meltwater channels. Grasslands developed in

the drier sites, woodlands in the wetter ones.

Aspen parkland proved ideal for European

settlement with its fertile soils. Today only 6%

of its original prairie is left, the rest consumed

by agriculture, the oil and gas industry and,

most recently, urban and suburban develop-

ment. Most of its remaining grasslands are

small, isolated, and few and far between.

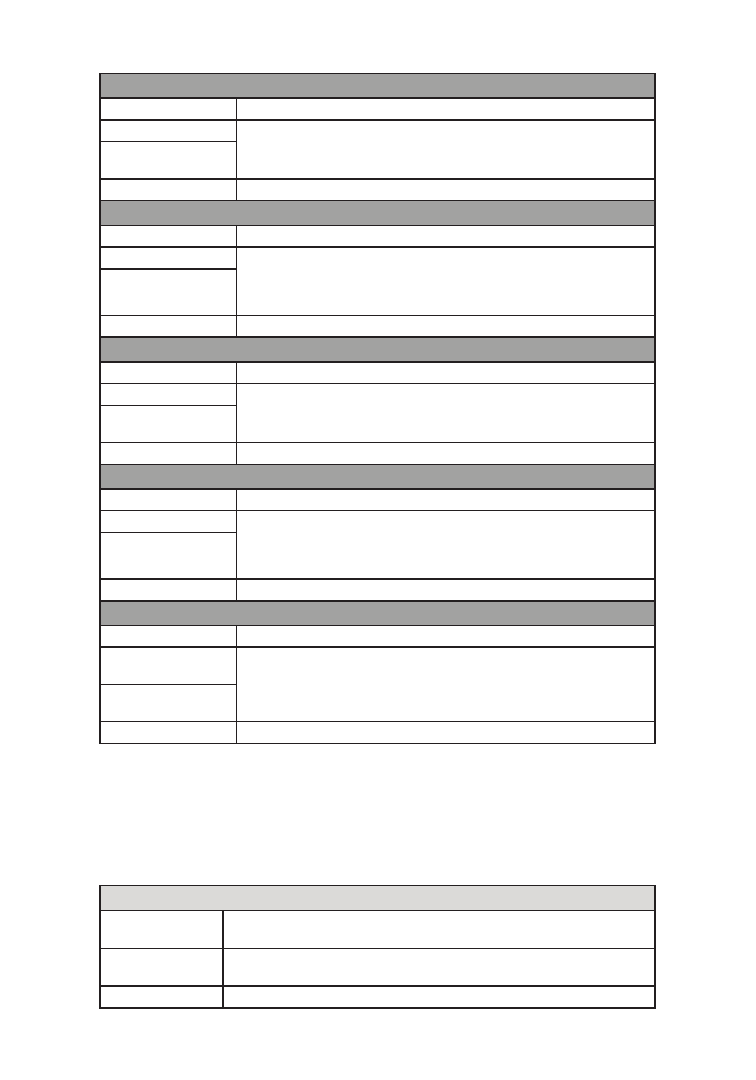

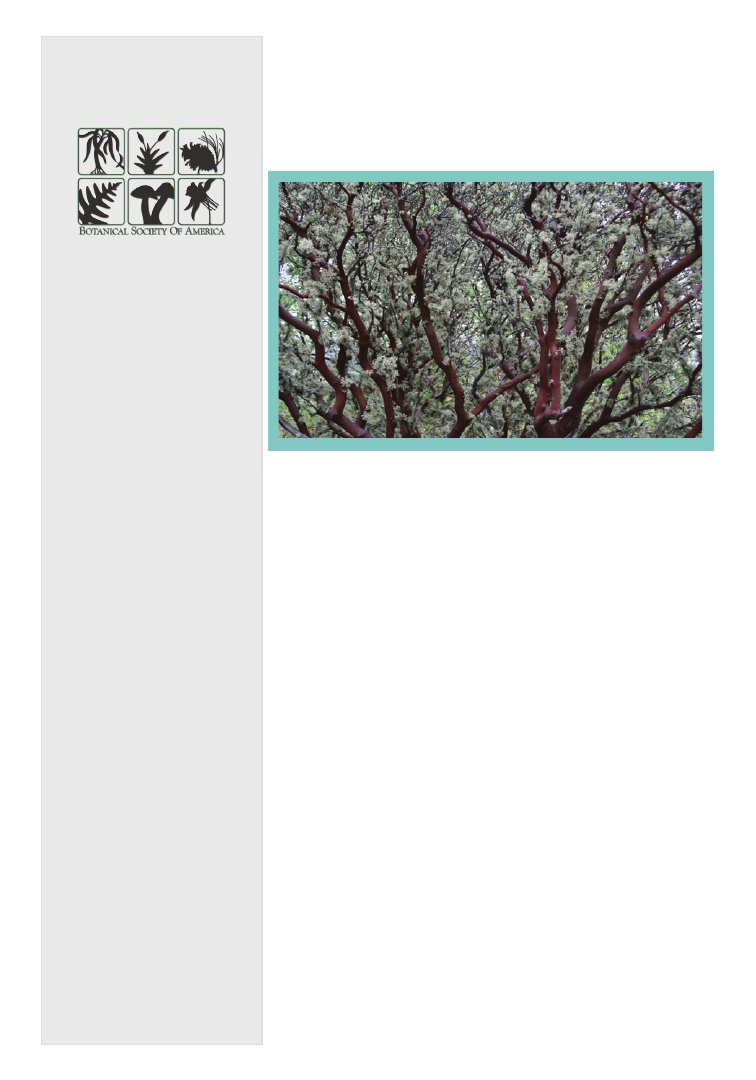

Figure 1. Nisku Prairie landscape in October

2015, showing aspen groves and interspersed

grassland. (Photo credit: Charles Richmond)

Nisku Prairie is one such remnant (Figure 1).

Twenty-three acres in extent, it is an L-shaped

parcel of largely native grassland bordered

and intruded by aspen groves. It is situated

on the west-facing, gently terraced slope of

the Gwynne Outlet Channel, which is incised

about 20 m into the surrounding plain. This

broad, shallow valley was eroded when Glacial

Lake Edmonton discharged through it some

10,000 years ago. On the other three sides, Ni-

sku Prairie is bordered by a road and acreage

residences. The municipality of Leduc County

has preserved it as a municipal reserve, allow-

able under the Municipal Government Act of

Alberta, which requires that 10% must be set

aside as public land when private land is sub-

divided for development.

In 1993 a local acreage owner “discovered” the

prairie with its rich assemblage of native flora.

Ecologists from the Government of Alberta

and the University of Alberta testified to its

ecological value as a rare remnant, and Leduc

County was persuaded to beef up its protec-

PSB 61 (4) 2015

Articles

140

tion of the reserve. With the approval of local

residents, the County staked out the boundar-

ies more carefully and erected a fence along all

but the western perimeter, along with a horse

gate for access, and appropriate signage. This

arrangement has been successful in keeping

out all-terrain vehicles, a major recreational

menace in rural areas, including supposedly

protected natural areas and reserves. On the

public side, a volunteer management commit-

tee was established. This cooperation was later

formalized in a Stewardship and Management

Agreement co-signed by Leduc County and

the Native Plant Council of Alberta, whose

local members contribute to the pool of vol-

unteer stewards.

A Diverse Grassland Flora

Small differences in topography, including

boulder outcrops, in soil type and moisture,

such as in shallow draws and west-facing

slopes, contribute to a diverse flora of over

180 species (including woodland species). The

dominant grass of the grassland component of

aspen parkland is plains rough fescue (Festuca

hallii), one of three rough fescue species that

comprise what was formerly considered a sin-

gle entity, the Festuca scabrella complex, now

recognized as the provincial grass emblem be-

cause of its ecological importance and cultural

significance as the basis of the ranching indus-

try in Alberta. Nisku Prairie’s large cover of

rough fescue grass (F. hallii) indicates conclu-

sively that it is an original grassland remnant,

as this grass does not regenerate once land has

been plowed. Somewhat enigmatically, which

seems to be true of many of the prairie rem-

nants in our area, Kentucky bluegrass (Poa

pratensis), considered to be an introduced

species, is also a major component. Nisku

Prairie’s soils belong to the Chernozemic and

Solonetzic orders, the former releasing Ca

2+

ions from weathering of the glacial sediments,

the latter Na

+

ions, with consequences for soil

structure and vegetation. Large patches of in-

termediate oat grass (Danthonia intermedia)

and mat muhly (Muhlenbergia richardsonis)

indicate solonetzic soils; in small spots where

the solonetz develops into hard pans lacking

vegetation, thickspike wheatgrass (Elymus

lanceolatus subsp. lanceolatus) is present.

(Many of our northern prairie remnants oc-

cur on solonetzic soils because they were dif-

ficult to cultivate; this protection does not un-

fortunately apply to rapid urbanization.)

Our most prized grass is Canadian ricegrass

(Piptatheropsis canadensis), a relative rarity

in Alberta. Among the eight species of sedge

(Carex) recorded, woolly sedge (Carex pelli-

ta) and graceful sedge (C. praegracilis) appear

to be the most prominent, especially in the

moist solonetzic areas. Dudley’s rush (Juncus

dudleyi) is common throughout the grassland

(Figure 2).

Figure 2. Plains rough fescue and three-flow-

ered avens. (Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill)

Among our typical herbaceous species of the

grassland are prairie crocus (Anemone patens),

PSB 61 (4) 2015

Articles

141

much esteemed as a harbinger of spring when

it blooms in early May, three-flowered avens

(Geum triflorum), two buttercups, prairie (Ra-

nunculus rhomboideus) and heart-leaved (R.

cardiophyllus), and heart-leaved alexanders

(Zizia aptera). A succession of flowers occurs

throughout June and July, including two spe-

cies of Arnica, slender blue beardtongue (Pen-

stemon procerus), golden-bean (Thermopsis

rhombifolia), field mouse-ear chickweed (Cer-

astium arvense), northern bedstraw (Galium

boreale), and veiny meadow-rue (Thalictrum

venulosum). Richardson’s alumroot (Heu-

chera richardsonii) and the white and graceful

cinquefoils (Drymocallis arguta and P. grac-

ilis) are also common, as is bastard toadflax

(Comandra umbellata). Petaloid monocots in-

clude prairie onion (Allium textile), common

blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium montanum)

and wood lily (Lilium philadelphicum). In wet

years we see a few specimens of the beauti-

ful calciphile white camas (Anticlea elegans).

Mid- to late-season blooms consist mostly

of Aster family members: five asters (Can-

adanthus and Symphyotrichum species), five

goldenrods (Solidago species), two sunflowers

(Helianthus spp.), meadow blazingstar (Lia-

tris ligulistylis), and narrow-leaved hawkweed

(Hieracium umbellatum). Three Artemisias

are the latest representatives of the family to

flower. Two other late bloomers of note are the

annuals felwort (Gentianella amarella) and

the hemi-parasite yellow owl’s-clover (Or-

thocarpus luteus) (Figure 3). Shrubs are well

represented in the moist soils of Nisku Prairie.

With the exception of a few willows, all are of

low stature. They include swamp gooseberry

(Ribes hirtellum), saskatoon (Amelanchier al-

nifolia) and common wild rose (Rosa wood-

sii). Narrow-leaved meadowsweet (Spiraea

alba) forms extensive patches in the wetter

areas and is at its western limit at the longi-

tude of Leduc. Western snowberry (Sym-

phoricarpos occidentalis), a major colonizer of

poorer-quality grasslands in aspen parkland,

forms occasional patches, especially on moist,

west-facing slopes.

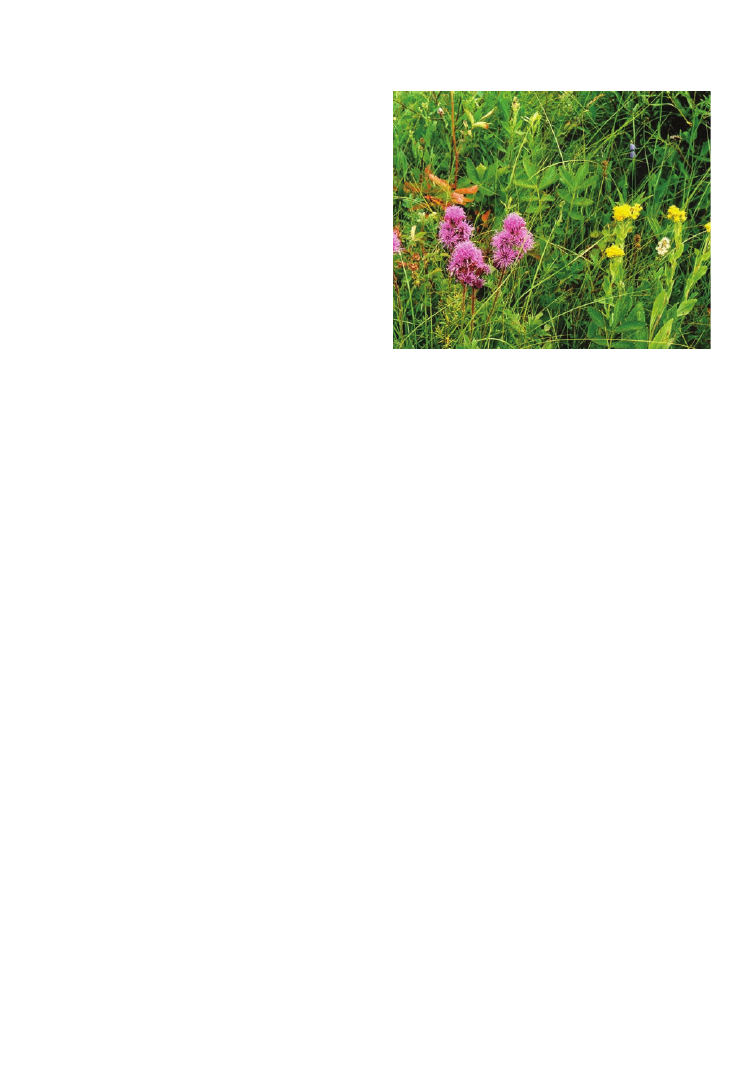

Figure 3. Grassland in midsummer, with a

variety of forbs, including meadow blazingstar

and stiff goldenrod. (Photo credit: Patsy Cotterill.)

The Challenges of

Managing a Prairie

Before European settlement of the aspen

parkland, grazing by bison, and fire (caused

by lightning or by aboriginal hunters), main-

tained grassland at the expense of suckering

aspen. Both these management methods are

difficult for small steward groups to employ

and the agricultural departments of munici-

palities often have other priorities than their

natural areas, as well as little expertise in burn-

ing for ecological purposes. Haying has been

employed by Leduc County in the past and we

hope to start a program of haying with litter re-

moval again next year. We have also established

two sets of experimental plots to determine the

effect of litter removal on plant growth.

Even after 20 years of intervention in the Prai-

rie, weed control continues to be a major man-

agement requirement. The great bane of natu-

ral areas throughout Alberta is the introduced

forage grass, smooth brome (Bromus inermis),

an aggressive colonizer of disturbed open ar-

eas that can also happily coexist as understo-

PSB 61 (4) 2015

Articles

142

ry in aspen woodland. Attempts at control of

brome colonies in the grassland have consist-

ed mostly of herbiciding with glyphosate. The

resulting patches of dead litter require repeat-

ed herbicide applications pending regenera-

tion with natives from surrounding grassland

or with transplants. Over the last half-dozen

years meadow foxtail (Alopecurus pratensis)

has become well established, likely getting its

start in the wet bottomlands of the Gwynne

Outlet and spreading up into the grasslands.

We are cutting and herbiciding it.

A heavily disturbed area near the gate where

rocks excavated from nearby fields were

dumped and then removed has been the focus

of volunteer efforts for the last few years. The

soil here is now so disturbed that we essential-

ly have a “garden,” with a seemingly inexhaust-

ible seed bank supply of annual and perennial

weeds such as stinkweed (Thlaspi arvense),

hemp-nettle (Galeopsis tetrahit), Canada this-

tle (Cirsium arvense), and sow-thistle (Son-

chus arvensis), along with smooth brome. We

have transplanted here seedlings and plugs

grown by volunteers from seed collected on

site or from the general area. The transplants

resemble those of the intact prairie communi-

ty neither in composition nor form. We grow

species that germinate easily and are robust in

habit, with the objective of creating as much

native ground cover as quickly as we can:

three-flowered avens, Richardson’s alumroot,

slender blue beardtongue, asters and golden-

rods, and various grasses. Natural succession

would eventually take care of the annuals, and

indeed patches of the perennial colonizer Soli-

dago canadensis complex are extensive, but we

assume that thistle and brome would persist

indefinitely among the natives if we did not re-

move them. We have not planted plains rough

fescue, despite the dominance of this grass in

mature prairies as its seedlings are unthrifty

and uncompetitive in early successional situ-

ations. Moreover, our Nisku populations have

not flowered significantly in four years, and

other sources of seed are few and far between

(Figure 4).

We are concerned that a number of native spe-

cies appear to have disappeared over the years,

usually those that were present originally in

small numbers. Examples include leathery

grape fern (Botrychium multifidum), Hooker’s

oatgrass (Avenula hookeri), long-leaved bluets

(Houstonia longifolia), and Drummond’s this-

tle (Cirsium drummondii). All of our grassland

species are wide-ranging in North America,

so their loss is only of local significance. Of

perhaps even greater concern is our suspicion

that numbers of commoner species are declin-

ing, which raises the question of whether this

is due to natural attrition, or our amateurish

and inconsistent management activities!

Our plans are to pay more attention to grass-

land health in the coming years, and to develop

a more scientific basis for assessing changes in

plant diversity. (A single-year inventory is not

sufficient. This year we had no appreciable rain

until late July, and several species did not flower

or flowered only in small numbers as a result.)

Figure 4. View of the disturbed rockpile area

near the gate, currently being transplanted with

native plugs. (Photo credit: Trudy Haracsi)

PSB 61 (4) 2015

Articles

143

Conservation of Grasslands

In many ways, the challenges of managing Ni-

sku Prairie are typical of those of small nat-

ural areas on publicly owned, provincial, or

municipal land. While the government can

prevail upon private industry to restore dis-

turbances caused by pipelines and other in-

dustrial activities, public money is not avail-

able for natural remnants whose purpose is

conservation or nature-oriented recreation.

The priority of urban municipalities is the

maintenance of parks and urban forests; for

rural ones it is agriculture and rural subdivi-

sions. Consequently, much of the stewardship

work falls on volunteers, who have their own

limitations: lack of equipment, appropriate

contacts and networks, expertise, time, and

availability. A somewhat brighter conserva-

tion and management picture is that of the

newly thriving land trusts, although even they

depend to a considerable extent upon volun-

teers for management (Figure 5).

The connectivity of small remnants to larger

natural landscapes is now recognized as of su-

preme importance for the long-term viability

of vegetation communities. Geographically,

Nisku Prairie is “connected” to the Gwynne

Outlet, which extends south into a deeper

valley supporting natural grassland commu-

nities. However, most of the acreage owners

have extended their properties, often used for

grazing horses, right down to the Channel

edge, severing an ecological connection. We

must likely accept that Nisku Prairie can make

no significant long-term contribution to the

conservation of grasslands in the aspen park-

land zone or in Alberta as a whole. Perhaps its

most important role then is anthropocentric

rather than ecocentric: to serve as a “living

museum” for public education and apprecia-

tion and for scientific study and experiment,

likely involving students from our various

post-secondary institutions. The continued

engagement of volunteers, especially younger

ones, is also vital, and we should be making

greater efforts at outreach.

Older people with farming backgrounds have

nostalgic ties to iconic species such as prai-

rie crocus, associations that can only lessen

in predominantly urban-raised populations.

Our stewardship goal should be to maintain

the health of the Nisku Prairie ecosystem for

as long as possible so that succeeding genera-

tions can appreciate our ancestral landscapes.

Such appreciation is basic to fostering attitu-

dinal changes that could mean that conserva-

tion of both small and large landscapes will

eventually be given the focus and the funding

it deserves.

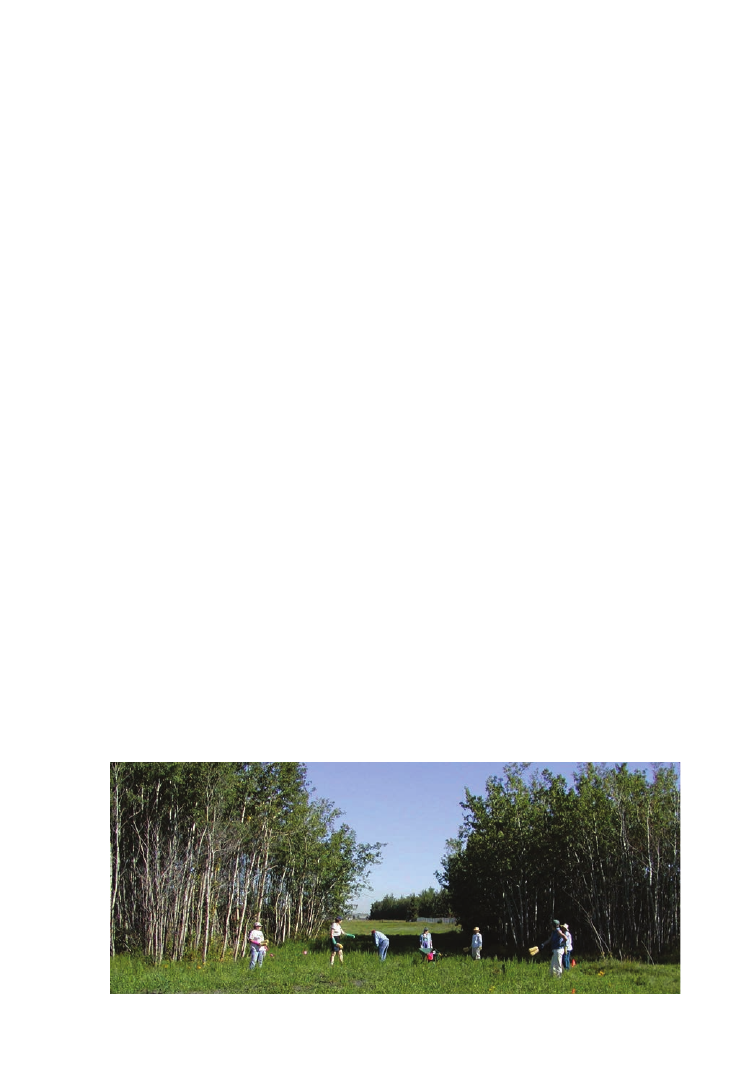

Figure 5. Volunteers “wicking” smooth brome and reed canarygrass with glypho-

sate in a disturbed area. (Photographer unknown.)

144

Announcements

Fred Sack (1947-2015)

Long-time BSA member Fred D. Sack died

on June 30, 2015, after a brief illness. He had

served as a Professor in the Department of

Botany at the University of British Columbia

from 2006 to his retirement in 2014 and as

Head of the department from 2006 to 2011.

Fred was born on May 22, 1947 in New York

City, the only child of Irving and Matilda Sack.

He graduated from Stuyvesant High School in

1964 and Antioch University in 1969, with a

degree in Sociology. While working in New

York City and living in Brooklyn, Fred en-

countered the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and

developed an interest in plants that eventually

led him to Cornell University for graduate school.

Fred received his Ph.D. from Cornell in 1982

for his research on stomatal development and

ultrastructure in the moss Funaria hygromet-

rica. A portion of Fred’s thesis appeared in the

American Journal of Botany in 1983, the first

of numerous AJB papers over his career. Af-

ter two years as a postdoctoral researcher at

In Memoriam

the Boyce Thompson Institute, Fred was hired

as an Assistant Professor in the Department

of Botany at The Ohio State University in

1984. He progressed through the ranks, and

remained there for 22 years. Fred’s research

interests in plants were broad and diverse and

included developmental anatomy, cell biology,

structure-function relationships, molecular

genetics, the cytoskeleton, and gravitational biology.

Fred’s interests in gravitational and space biol-

ogy led to extensive involvement with NASA

advisory boards, grants panels, and working

groups. He served on the National Acade-

my of Sciences Committee on Space Biology

and Medicine, the Space Studies Board, and

the National Research Council. From 1991

to 1993, Fred served on the Board of Direc-

tors of the American Society for Gravitational

and Space Biology; in 2004, he was awarded

the NASA Public Service Medal, and in 2005

he was appointed a Fellow of the American

Academy for the Advancement of Science.

Fred served as an Associate Editor for the AJB

from 2005 to 2013.

Over the course of his scholarly career, Fred

published over 110 papers and supervised

scores of graduate students and postdocs. He

was known for his enthusiasm, incisive think-

ing, quick wit, and collegial nature. Fred is

survived by his wife, Dian Clare, her three