P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

Fall 2013 Volume 59 Number 3

In This Issue..............

Botany 2013!.....p. 146

More BSA awards announced at

Botany 2013.....p. 80

Botany in Action - in New Orleans!

PlantingScience mentors

make a difference.....p. 90

From the Editor

Fall 2013 Volume 59 Number 3

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 59

-Marsh

Elizabeth Schussler

(2013)

Department of Ecology &

Evolutionary Biology

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-1610

eschussl@utk.edu

Christopher Martine

(2014)

Department of Biology

Bucknell University

Lewisburg, PA 17837

chris.martine@bucknell.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Department of Biological Sci-

ences & Biochemistry Program

Smith College

Northampton, MA 01063

Tel. 413/585-3687

Lindsey K. Tuominen

(2016)

Warnell School of Forestry &

Natural Resources

The University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30605

lktuomin@uga.edu

Daniel K. Gladish

(2017)

Department of Botany &

The Conservatory

Miami University

Hamilton, OH 45011

gladisdk@muohio.edu

The good news these days is about resources. There is

so much information readily available on the internet

that one hardly needs to leave the office to work on a

literature review or gather information for a lecture.

The first step—Google it! The bad news these days is

about resources. There is so much information readily

available on the internet that one could spend hours

sorting through possible sites to find the information

you want. What we need is a resource that has done

the dirty work of searching what is available and evalu-

ating its usefulness. That resource has been provided

for botanical and lichenological systematic research

by Morgan Gostel, Manuela Dal-Forno, and Andrea

Weeks in this issue. This is also a great resource to use

for teaching images.

In our other feature article, Melanie Link-Pérez and

Elizabeth Schussler

demonstrate that resources, by

themselves, are not enough to support grade-school

teachers in their efforts to introduce plant science to

students. At this age the kids love plants and so do

the teachers, and the teachers are anxious to find and

use resources to help them incorporate plants into the

curriculum. What they need even more, however, is

greater exposure to plant-based activities in their pre-

service training. Are you looking for broader impact?

Here is a defined target to aim for. Collaborations with

individual schools or individuals teachers are great,

but collaborations with teacher trainers in education

departments will have much greater overall impact.

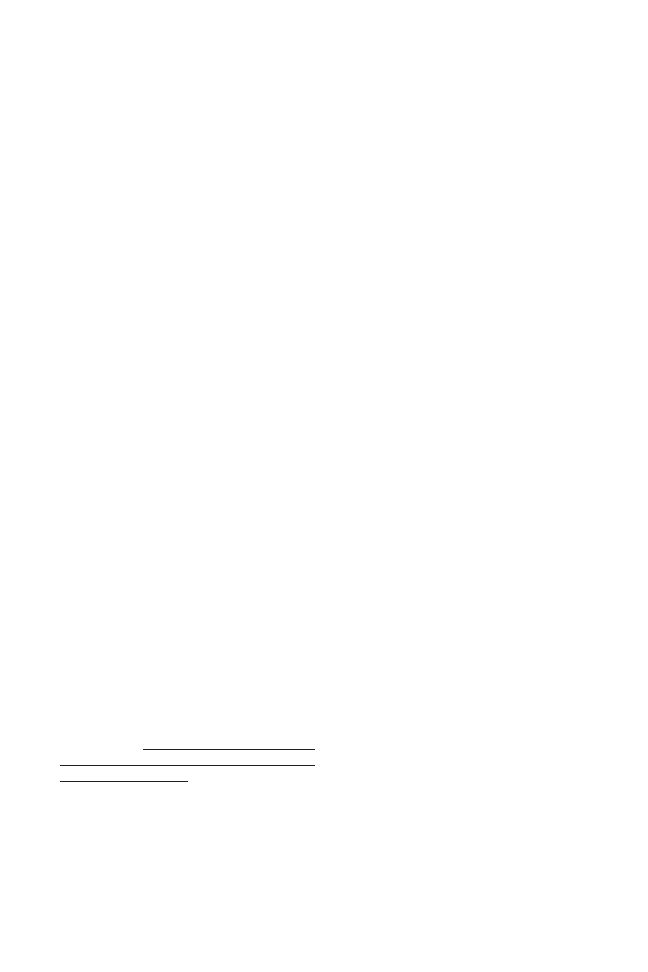

By the way, if you were not in New Orleans, you

missed a GREAT conference. It took the Society 37

years to go back to New Orleans for an annual meet-

ing, but I don’t think we’ll wait that long to visit again.

But that’s behind us now, and mostly below sea level.

Next year we’ll be back on higher ground—look for-

ward to Boise.

77

Table of Contents

Society News

More Awards for Botany 2013 .........................................................................................80

Second Annual BSA Public Policy Committee Capitol Hill Visit ....................................85

BSA Seeks Editor for the Plant Science Bulletin .............................................................87

Botany in Action in New Orleans .....................................................................................88

BSA Science Education News and Notes ......................................................

90

Editor’s Choice Review .................................................................................

94

Announcements

Bullard Fellowships in Forest Research ...........................................................................95

American Philosophical Society Grants ...........................................................................95

English - Spanish/Spanish - English Dictionary of Botany Now Available .....................96

A Learning Gap is Filled with Plants ...............................................................................97

Reports

How Teachers Teach about Plants ....................................................................................99

A Navigation Guide to Cyberinfrastructure Tools for Botanical and Lichenological

Systematics Research . ..........................................................................................111

Book Reviews

Bryological .....................................................................................................................131

Developmental and Structural ........................................................................................133

Ecological .......................................................................................................................134

Economic Botany ...........................................................................................................136

Systematics ....................................................................................................................138

Books Received ...........................................................................................

144

The Boise Center

July 26-30, 2014

www.2014.botanyconference.org

78

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

79

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Congratulations to all

Botany 2013 Award Winners

For a complete listing of Awards and Winners see: http://botany.org/awards_grants/2013Awardrecipients.php

80

Society News

Award Winners

In the last edition of the Plant Science Bulletin

(http://botany.org/plantsciencebulletin/PSB-

2013-59-2.pdf), we listed a number of Botanical

Society of America award winners. We’re pleased to

continue the list of winners in the following pages.

Jeanette Siron Pelton Award

The Jeanette Siron Pelton Award is given for

sustained and imaginative productivity in the field

of experimental plant morphology.

Professor Mitsuyasu Hasebe, National Institute

for Basic Biology (Japan)

The 2013 Grady L. Webster

Award

This award was established in 2006 by Dr.

Barbara D. Webster, Grady’s wife, and Dr. Susan V.

Webster, his daughter, to honor the life and work

of Dr. Grady L. Webster. The American Society of

Plant Taxonomists and the Botanical Society of

America are pleased to join together in honoring

Grady Webster.

Drs. Jessica M. Budke, Bernard

Goffinet, and Cynthia S. Jones. The

cuticle on the gametophyte calyptra

matures before the sporophyte cuticle in the

moss Funaria hygrometrica (Funariaceae)

American Journal of Botany, 2012, 99(1): 14-22

http://www.amjbot.org/content/99/1/14.full.

pdf+html

GIVEN BY THE SECTIONS

Margaret Menzel

Award (Genetics Section)

The Margaret Menzel Award is presented by

the Genetics Section for the outstanding paper

presented in the contributed papers sessions of the

annual meetings.

This year’s award goes to Dr. Ingrid Jordon-

Thaden, University of Florida, for the paper

“Differential gene expression and loss in two natural

and synthetic allotetraploid Tragopogon species

(Asteraceae) and their diploid progenitors”

Co-authors: Lyderson Viccini, Richard Buggs,

Michael Chester, Ana Veruska Cruz Da Silva,

Srikar Chamala, Ruth Davenport, Wei Wu, Patrick

S. Schnable, W. Brad Barbazuk, Douglas Soltis and

Pamela Soltis

http://www.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=936

George R. Cooley Award

(Systematics Section and

the American Society of Plant

Taxonomists)

The ASPT’s Cooley Award is given for the best

paper in systematics given at the annual meeting

by a botanist in the early stages of his/her career.

Awards are made to members of ASPT who are

graduate students or within 5 years of their post-

doctoral careers. The Cooley Award is given for

work judged to be substantially complete, synthetic,

and original. First authorship required; graduate

students or those within 5 years of finishing their

Ph.D. are eligible; must be a member of ASPT at

time of abstract submission; only one paper judged

per candidate.

This year’s award was given to Ricardo Kriebel of

the New York Botanical Garden for the talk

“Phylogenetic study of Conostegia demonstrates

the utility of anatomical and continuous characters

in the systematics of the Melastomataceae.” Co-

author: Fabian Michelangeli

http://www.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=584

81

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

A.J. Sharp Award

(Bryological and Lichenological

Section)

The A.J. Sharp Award is presented each year by the

American Bryological and Lichenological Society

and the Bryological and Lichenological Section for

the best student presentation. The award, named

in honor of the late Jack Sharp, encourages student

research on bryophytes and lichens.

This year’s A.J. Sharp Award goes to Matthew

Nelsen, University of Chicago, for his paper

“Lichen-associated algae: we hardly know you.” Co-

author: Steven D. Leavitt

http://www.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=832

Edgar T. Wherry Award

(Pteridological Section and the

American Fern Society)

The Edgar T. Wherry Award is given for the best

paper presented during the contributed papers

session of the Pteridological Section. This award is

in honor of Dr. Wherry’s many contributions to the

floristics and patterns of evolution in ferns.

This year’s award goes to Sally Stevens,

Purdue University, for her paper; “No Place

Like Home? Testing for Local Adaptation

and Dispersal Limitation in the Fern Vittaria

appalachiana (Vittariaceae)” Co-author: Nancy

Emery

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=732

AWARDS FOR EARLY CAREER

SCIENTISTS

Lawrence Memorial Award

The Lawrence Memorial Fund was established

at the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation,

Carnegie Mellon University, to commemorate the

life and achievements of its founding director, Dr.

George H. M. Lawrence. Proceeds from the Fund

are used to make an annual Award in the amount

of $2000 to a doctoral candidate to support travel

for dissertation research in systematic botany or

horticulture, or the history of the plant sciences.

The recipient of the Award is selected from

candidates nominated by their major professors.

Nominees may be from any country and the Award

is made strictly on the basis of merit—the recipient’s

general scholarly promise and significance of the

research proposed. The Award Committee includes

representatives from the Hunt Institute, The Hunt

Foundation, the Lawrence family, and the botanical

community.

The Lawrence Memorial Award for 2013 goes

to Aleksandar Radosavljevic, student of Dr.

Patrick Herendeen of the Chicago Botanical

Garden and Northwestern University. The proceeds

of the award will help support his travel for field

and collections-based work in integrative research

study of the genus Cynometra.

BSA Public Policy Award

The Public Policy Award was established in 2012.

Kathryn Ann Lecroy, University of Pittsburgh,

Advisor: Lindsey Tuominen

Michael Cichan Award

(Paleobotanical Section)

This award was named in honor of the memory

and work of Michael A. Cichan, who died in a

plane crash in August of 1987, and was established

to encourage work by young researchers at the

interface of structural and evolutionary botany.

This award is given to a young scholar for a paper

published during the previous year in the fields of

evolutionary and/or structural botany.

The Michael Cichan Award for 2013 is presented

to Anne-Laure Decombeix, French National

Center for Scientific Research at UMR AMAP

Montpellier.

82

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Isabel Cookson Award

(Paleobotanical Section)

Established in 1976, the Isabel Cookson Award

recognizes the best student paper presented in the

Paleobotanical Section.

Dori Contreras from the University of

California-Berkeley, is the 2013 award recipient

for the paper, “New data on the structure and

phylogenetic position of an extinct Cretaceous

redwood.” Co-authors: Garland Upchurch and Greg

Mack.

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=749

Katherine Esau Award

(Developmental and Structural

Section)

This award was established in 1985 with a

gift from Dr. Esau and is augmented by ongoing

contributions from Section members. It is given to

the graduate student who presents the outstanding

paper in developmental and structural botany at

the annual meeting.

This year’s award goes to Luke Nikolov, from

Harvard University, for the paper “Developmental

origins of the world’s largest flowers.” Co-authors:

Peter Endress, M Sugumaran, Sawitree Sasirat,

Suyanee Vessabutr, Elena Kramer and Charles Davis.

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=874

Maynard Moseley Award

(Paleobotanical and

Developmental and Structural

Sections)

The Maynard F. Moseley Award was established

in 1995 to honor a career of dedicated teaching,

scholarship, and service to the furtherance of the

botanical sciences. Dr. Moseley, known to his

students as “Dr. Mo,” died Jan. 16, 2003 in Santa

Barbara, CA, where he had been a professor since

1949. He was widely recognized for his enthusiasm

for and dedication to teaching and his students,

as well as for his research using floral and wood

anatomy to understand the systematics and

evolution of angiosperm taxa, especially waterlilies

(Plant Science Bulletin, Spring, 2003). The award is

given to the best student paper, presented in either

the Paleobotanical or Developmental and Structural

sessions, that advances our understanding of plant

structure in an evolutionary context.

Robert A. Stevenson, from University of

California - Berkeley, is the 2013 Moseley Award

recipient for his paper “Flight of the conifers:

Reconstruction of the flight characteristics of

Paleozoic winged conifer seeds.” Co-authors:

Dennis Evangelista and Cindy V. Looy.

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=328

Samuel L. Postlethwait Award

(Teaching Section)

The Samuel L. Postlethwait Award is given by

the Teaching Section of the BSA for outstanding

service to botanical education.

This year’s award goes to Dr. James Wandersee,

Louisiana State University.

Developmental & Structural

Section Student Travel Awards

Abigail Mazie, University of Wisconsin-

Madison - Advisor, Dr. David Baum—Botany

2013 presentation: “Understanding cell shape

diversity: the evolution of stellate trichomes in

Physaria (Brassicaceae)” Co-author: David Baum

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=331

Adrian Dauphinee, Dalhousie University -

Advisor, Dr. Arunika Gunawardena—Botany

2013 presentation: “Comparison of the early

developmental morphologies of Aponogeton

madagascariensis and Aponogeton boivinianus.”

Co-authors: Christian Lacroix and Arunika

Gunawardena

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=911

Lachezar Nikolov, Harvard University - Advisor,

Dr. Charles Davis—Botany 2013 presentation:

“Developmental origins of the world’s largest

flowers.” Co-authors: Peter Endress, M Sugumaran,

Sawitree Sasirat, Suyanee Vessabutr, Elena Kramer

83

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

and Charles Davis

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=874

Li-Fen Hung, National Taiwan University -

Advisor, Dr. Ling-Long Kuo-Huang—Botany 2013

presentation: “The growth strain and anatomical

characteristics of tension wood in artificially

inclined seedlings of Koelreuteria henryi Dummer.”

Co-author: Ling-Long Kuo-Huang

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=135

Bhawana Bhawana, Middle Tennessee State

University - Advisor, Dr. Aubrey B. Cahoon - Botany

2013 presentation: “Visualization of 3-Dimensional

Plant Cell Architecture with FIB-SEM.” Co-authors:

Joyce Miller and Aubrey Cahoon

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=265

Developmental & Structural

Section Best Student Poster

Award

Katie Downing, Eastern Michigan University,

for the poster “A S.E.M. survey of Carnivorous

North American Purple Pitcher Plant Leaves,

Sarracenia purpurea (Sarraceniaceae).” Co-author:

Margaret Hanes

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=600

Ecology Section

Undergraduate Student

Presentation Award

Jenna Annis, Eastern Illinois University,

for the paper “Seed Ecology of Federally

Threatened Pinguicula ionantha (Godfrey’s

Butterwort).” Co-authors: Jennifer O›Brien, Janice

Coons, Brenda Molano-Flores and Samantha

Primer

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=335

Nia Johnson, Howard University, for the poster

“Herbivory Response of Murgantia histrionica to

a Ni-hyperaccumulator, Alyssum murale.” Co-

authors: Chandler Puritty and Mary McKenna

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=507

Chandler Puritty, Howard University, for

the poster “Herbivory Response of Murgantia

histrionica to a Ni-hyperaccumulator, Alyssum

murale.” Co-authors: Nia Johnson and Mary

McKenna

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=507

Ecology Section Graduate

Student Presentation Award

Ian Jones, Florida International University,

for the paper “Temporal and developmental

changes in extrafloral nectar production in Senna

mexicana var. chapmanii: is extrafloral nectar an

inducible defense?”

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=162

Ecology Section Student

Poster Award

Jordan Ahee, Trent University, for the poster

“Evidence of restricted pollen dispersal in Typha

latifolia.” Co-authors: Marcel Dorken and Wendy

Van Drunen

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=930

Economic Botany Section

Student Travel Awards

Taylor Nelson, Weber State University - Advisor,

Dr. Sue Harley, for the paper “Survey for helenalin

among Utah Asteraceae species.”

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=357

Sushil Paudyal, Old Dominion University -

Advisor, Dr. Govind P. S. Ghimire, for the paper

“Plants used in religious ceremonies by Tharu

culture in Dang Valley (Nepal).”

http://www.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=861

84

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Tropical Biology Section Best

Student Paper Award

Beyte Barrios Roque, Florida International

University, for the paper “Herbivory in fragmented

populations of the Pineland golden trumpet

(Angadenia berteroi).” Co-authors: Andrea Salas

and Suzanne Koptur

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=117

Laura Lagomarsino, Harvard University, for

the paper “Of Bats, Birds, and Berries: Phylogeny

and Evolution of the Species-Rich Neotropical

Lobelioids (Campanulaceae).” Co-author: Charles

Davis

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=752

Melissa Johnson, Claremont Graduate

University, for the paper “Evolution of reproductive

barriers within a non-adaptive hyper-species-rich

radiation of Hawaiian Cyrtandra (Gesneriaceae).”

Co-author: Elizabeth Stacy

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=702

Genetics Section Student

Poster Award

Meng Wu, Miami University, for the poster “The

investigation on protein evolution of Y chromosome

in Carica papaya.” Co-author: Richard Moore

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=581

Physiological Section

Li-Cor Prize

Samuel Del Rio, California State University -

Bakersfield, for the paper “Hydraulic conductance

is coordinated at the leaf and stem levels among

chaparral shrubs.” Co-authors: Christine Hluza,

Evan D. MacKinnon, Jeffrey Parker and R. Pratt

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=812

Physiological Section Best

Student Paper Award

Kerri Mocko, University of Connecticut - Advisor,

Dr. Cynthia Jones, for the poster “Physiological

responses to drought reflect phylogenetic history

in South African Pelargoniums (Geraniaceae).” Co-

author: Cynthia Jones

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=302

Physiological Section Best

Student Poster

Robert “Berto” Griffin-Nolan, Ithaca College -

Advisor, Dr. Peter Melcher, for the poster “The

physiological responses of moss to greenlight.” Co-

author: Peter Melcher

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=73

Marta Percolla, University of Connecticut -

Advisor, Dr. Cynthia Jones, for the poster “Reduced

number of vessel connections is positively

associated with greater cavitation resistance to

water stress in chaparral shrubs” Co-authors: R.

Pratt, Anna Jacobsen and Michael Tobin

http://2013.botanyconference.org/engine/

search/index.php?func=detail&aid=823

85

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Lindsey’s Experience:

Although I have previously participated in

science policy in small ways, I had never before

been to Capitol Hill or spoken in person with any

federal policymaker. Curious about the world of

science policy, I was keen to attend the science

policy career panel sponsored by the Ecological

Society of America, receive training from AIBS,

and discuss support for NSF with policymakers.

The career panel included Alan Thornhill, the

Director of the Office of Science Quality and

Integrity with the USGS; Laura Petes, Ecosystem

Science Advisor with the Climate Program Office

at NOAA; Ari Novy, Public Program Manager

of the US Botanical Gardens; and Penny Firth,

the Deputy Division Director for the Division of

Environmental Biology at NSF. As one might guess

from the range of job titles, learning about these

individuals’ career paths and day-to-day working

life helped attendees better understand the diverse

options available for PhD-level scientists to serve in

the federal government. Dr. Thornhill pointed out

that science is highly respected and influential

within the federal government when it has a seat

at the table, but policymakers may not always

remember to include science. Thus, scientists

can potentially have a transformative effect on

public policy. Students considering science policy

work should note that, while the ability to think

scientifically is highly valued in such careers, a deep

expertise in one area is less important than broad,

interdisciplinary knowledge and a collaborative

work orientation.

The training session was serendipitously timed,

as the President’s 2014 Budget Proposal had been

released earlier that day. BESC co-chairs Nadine

Lymn and Robert Gropp and AIBS Senior Public

Policy Associate Julie Palakovich Carr gave

an overview of the federal budget process, the

impacts of the sequester and proposed budget on

federal research funding, and tips on effectively

communicating with federal policymakers.

It became clear in their mock Capitol Hill

meetings that the way scientists usually discuss

their research needs to be distilled even from

an “elevator pitch” to a simple fifteen-second

summary highlighting the work’s broader

impacts!

This year (2013) marks the first year that the

BSA Public Policy Committee has offered a Public

Policy Award. This award supports student and

early career BSA-member applicants to travel to

Washington, D.C. and participate in the annual

Biological and Ecological Sciences Coalition

(BESC) Congressional Visits Day. This two-day

event is co-organized by the BESC and American

Institute for Biological Sciences (AIBS) and is

attended by scientists from around the United

States. During the first day, participants receive

training in effective communication with policy

makers, followed by an opportunity for the

constituent scientist participants to meet with their

elected representatives and senators to discuss the

impact and importance of federal funding for basic

research in the biological sciences.

Last year, former BSA student representative to

the Board, Dr. Marian Chau, and current student

representative, Morgan Gostel, participated in

the event. The success of the event resulted in the

establishment of the annual BSA Public Policy

Award by the BSA Public Policy Committee

and the BSA Awards Committee. This year, two

BSA members, Dr. Lindsey Tuominen and Kate

LeCroy (PhD student), received the first of these

awards. The awardees were joined by BSA student

representative, Morgan Gostel (a PhD Candidate

located at George Mason University, in close

proximity to D.C.). The three attendees share their

experience in this article.

As we are all well aware, Congressional

partisanship has reached historic levels and is

resulting in significant budget uncertainty, which

has permeated all levels of government and affected

the amount of funds available for biological

research. Biological research touches all of our

lives, whether spurring innovation, improving

food security, or protecting biodiversity and

understanding the needs of a healthy ecosystem.

There is a substantial return on the investment

in basic research, including the maintenance of a

well-trained workforce prepared to face mounting

global challenges ahead. The Congressional Visits

Day provides a unique opportunity for researchers

to meet with members of Congress and share their

experience as citizens, educators, and researchers.

Second Annual BSA Public Policy Committee Capitol Hill Visit

86

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

of Pittsburgh and a Pennsylvania voter, I joined

the team of students visiting congress members

of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and the District of

Columbia, specifically Senator Mikulski (D-

MD), Senator Cardin (D-MD), Representative

Hoyer (D-MD), Representative Norton (D-D.C.),

Representative Cummings (D-MD), Senator Casey

(D-PA), Senator Toomey (R-PA), Representative

Thompson (R-PA), Representative Brady (R-PA),

and Representative Doyle (R-PA). Our message

was simple yet strong: sustain investments in

basic biological research.

In regard to my state of Pennsylvania, Senator

Casey and his science policy staffer were open and

honest about the hard times of sequestration but

stated that investing in federal science funding at a

predictable level was a high priority. Representative

Thompson was polite and receptive to our message

while he leaned more toward supporting applied

research and research that could be commercialized

for economic benefit. Senator Toomey’s science

staffer was thankful for the stories I shared about

how federal science funding has benefited my

University’s department of biological sciences, and

he agreed with us that funding basic research can

lead to solving problems and making advances for

society. Lastly, the staffer of my own Pittsburgh

Representative Doyle was happy to tell us that he

signed a statement circulating around the House

floor in support of the significant increases in federal

science funding described by the president’s budget.

Every congress member or their staffer specifically

voiced their pleasure to hear that not only does

federal science funding support the scientist, but

that there is an increasing commitment to bring

our science out to our communities.

Beyond active research, we cannot secure

the future of science without cultivating strong

relationships with non-scientists and future

scientists. This relationship should be especially

strong with decision-makers, because as members

of their constituency, we must maintain a stable

voice to make the most positive and informative

impact that we can. I encourage those interested

in cultivating these relationships to increase your

civic engagement and consider participating in

Congressional Visits Day 2014!

Morgan’s Experience:

This marked my second year participating in

the Congressional Visits Day. Despite living and

On April 11, led by neuroscientist and AIBS

Policy Intern Dr. Zach Rosner, Margaret Kosmala

(PhD Candidate, University of Minnesota/National

Museum of Natural History), Andrew Adrian

(PhD Candidate, University of Iowa), and I met

with Senate staff members representing Minnesota

(Klobuchar and Franken), Iowa (Grassley), and

Illinois (Durbin) and Representative staff members

representing Minnesota (Ellison and McCollum),

Illinois (Davis), and Andrew’s home state of

Alabama (Aderholt). In discussing NSF’s basic

research funding, we came to realize that most

elected officials were highly receptive to our message

and supportive of basic biological research—cause

for optimism that the relatively restricted impacts

on NSF funding President Obama has proposed

for 2014 will be supported within the legislative

branch.

Throughout the trip, we were immersed in the

world of scientists who had chosen what is often

considered “one” alternative career path from the

perspective of academic scientists. While the AAAS

Science & Technology Policy Fellowships seem

to be the most common way that scientists enter

this world, the diverse options within the science

policy career path were evident. Meeting Jasmine

Hunt, Legislative Assistant to Senator Durbin, and

Anna Henderson, an Energy Fellow with Senator

Franken, further reinforced this idea—Dr. Hunt

has training in chemistry and Dr. Henderson in

geology. I am really honored that BSA gave me the

opportunity to get this view of the science policy

world, and I strongly encourage graduate students

considering a career outside academia to apply for

the BSA Policy Award in 2014!

Kate’s Experience:

The Public Policy Award of the BSA afforded

me the incredibly rewarding experience of civic

engagement during a critical time for decision-

making of our congressmen and congresswomen. I

attended the science policy career panel discussion

with Lindsey, and I also enjoyed the dialogue that

I’ve often pondered but have not found easily

accessible until now. Following this panel, we

attended a boot camp on current science public

policy topics—in fact, the most recent topic, the

President’s new fiscal year budget, was released

the day of our workshop—and the gifted policy

analysts at AIBS quickly read through it and had

prepared a presentation, along with a summary of

the projected impacts of sequestration on federal

science agencies. As a student at the University

87

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

be made a partisan issue! Your continued support

of science policy can be as easy as joining the

AIBS Action Center, which provides notification

of important science policy news (

http://capwiz.

com/aibs/home/

), and you can also play a role by

joining the growing BSA Public Policy Committee

(Contact Marian Chau for more information:

marianmchau@gmail.com).

We thank the membership of the BSA for

supporting this outreach opportunity to enhance

basic scientific research policy by allowing

young, active members of the botanical research

community to participate in this capacity.

By Morgan Gostel, Lindsey Tuominen, and Kate LeCroy

pursuing my PhD only 45 minutes outside of

Capitol Hill, this is one of very few opportunities

I have to meet with and speak directly to

policymakers on the Hill. With regard to funding

uncertainty, the contrast between this year and

the last is remarkable. President Obama’s budget

proposal for fiscal year 2014 was released only two

hours before the CVD briefing session (day one of

the two-day event), so it was not until the morning

of our congressional visits that specific details could

be clarified regarding how the budget request might

affect federal science agencies. These details were

important, as the FY 2014 spending plan includes

several proposals that support increases to science

funding; among these is a $741 million increase to

the current NSF budget.

I co-led my team (with Richelle Weihe, Federal

Grants and Contracts Coordinator at the Missouri

Botanical Garden) this year, which included

scientist constituents from Missouri, North

Carolina, and Virginia. Richelle represented

Missouri and met with staffers from the offices

of Representative Clay (D-MO) and Senator

McCaskill (D-MO), while I met with staffers from

the offices of Virginia Representative Connolly

(D-VA) and Senator Warner (D-VA). Also in our

team were two other graduate students: Gar Secrist,

who was preparing to defend his Masters Thesis

from the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences,

and Erin McKenney, a North Carolina resident

and PhD student studying at Duke. Gar met with a

legislative aid from Representative Wittman’s office

(R-VA), while Erin had meetings with a legislative

aid for Senator Hagan (D-NC) and met directly

with Representative Price (D-NC). Although our

meetings with elected representatives included

members with a range of political ideology, the

message we had was generally well received. We were

cautioned that the gulf of partisan divide remains

wide and that it is likely that much congressional

debate will continue before components of the

President’s proposed spending plan can be adopted.

As constituents and members of the BSA,

you too can push for support of science funding

simply by writing your elected members of

Congress and asking them to support the

President’s FY 2014 proposed spending plan for

the sciences. Tell your elected officials how federal

funding for science impacts your research, your

community, and the next generation of researchers

who will drive global leadership in innovation.

Request not only sustained support for the sciences,

but a commitment to support this valuable

investment. Science funding is not and should not

BSA Seeks Editor for

Plant Science Bulletin

The Botanical Society of America (BSA) is

soliciting nominations for the position of Editor

of the Plant Science Bulletin (PSB) to serve a

five-year term, beginning January 2015. Both

self- nominations and nominations of others are

welcomed.

This is a rare leadership opportunity to contribute

to the Society and the continued evolution of the

PSB. We seek someone with desire to pursue

innovation and explore new ways to serve the

Society.

Duties of the Editor include both aspirational

responsibility (helping shape a strategic vision for

PSB, along with the PSB Editorial Committee and

BSA Publications Committee) and operational

responsibilities (soliciting contributions,

coordinating reviews, working with Society office

staff to produce copy, and recruiting new Editorial

Committee members). Qualities of candidates

should include a broad familiarity with different

botanical specializations and especially botanical

education, excellent communication skills, and a

strong commitment to the Bulletin.

Review of nominations will begin on November

15, 2013. For the first stage of the review process,

please submit a brief letter of nomination and

a detailed vita of the nominated individual to

Dr. Sean Graham, Search Committee Chair at

swgraham@mail.ubc.ca.

The Committee may request additional

information from candidates as the search process

progresses. If you have questions or comments,

please contact Dr. Graham.

88

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

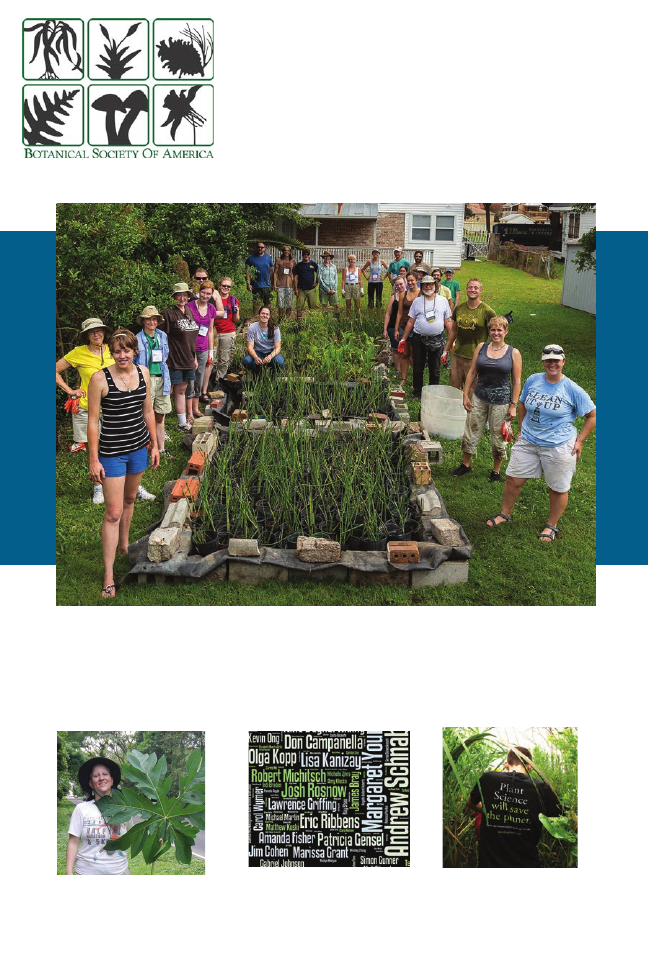

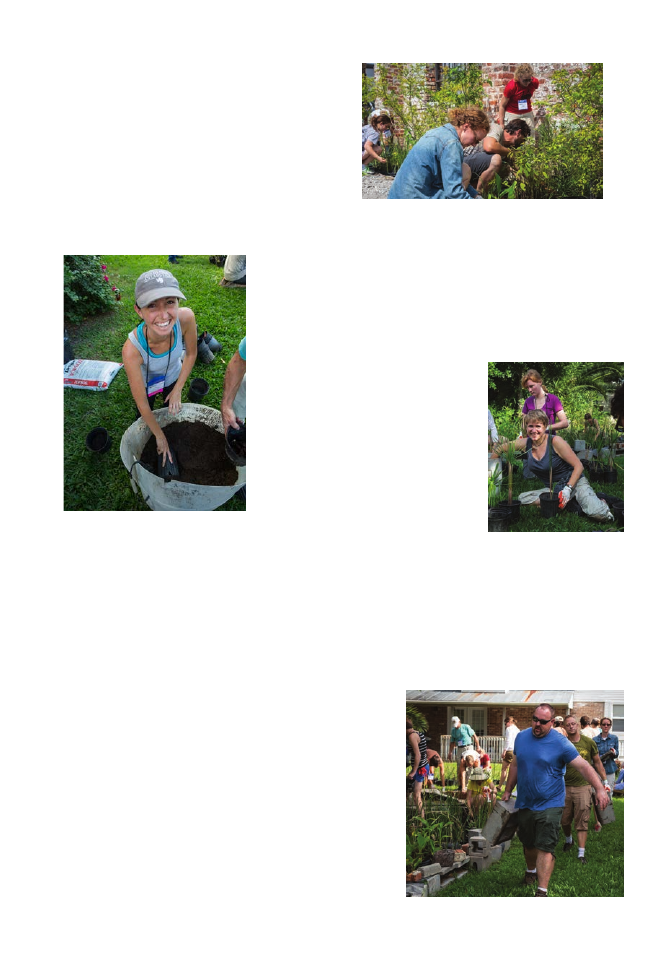

Botany in Action Project

Helps Bayou Rebirth Restore

Wetlands Plants

Give a botanist a day off and a chance to make a

difference, and what happens?

Well, if the example is that of 75 botanists at

the Annual Conference of the Botanical Society

of America, they put their hands and backs into

restoration of the Louisiana wetlands.

Every year during the conference, BSA organizes

a Botany in Action field trip, giving the members a

chance to give back to the host community. In 2013,

that field trip was organized around Bayou Rebirth,

a New Orleans non-profit devoted to hands-on

wetlands restoration and stewardship.

“We offer volunteers and students an opportunity

to engage in environmental restoration in a real

way and learn about the issues facing an incredibly

diverse, ecologically valuable, and significantly

degraded ecosystem in their backyard,” says Colleen

Morgan, founder and director of the program,

which is affiliated with Tulane University.

But not every volunteer group is quite like

the botanists that poured off the bus in late July,

ready with plant savvy and ready to learn about

the Louisiana plants they were going to tackle.

The group started in the backyard of an urban

neighborhood, where Bayou Rebirth had a variety

of gardens with native plants. They planted new

seeds, moved garden beds, weeded, dug, and

toted blocks. All the work was accomplished

while they fired off questions about the plants

they were working with and the native habitat

and environmental impact of the hurricanes and

flooding of the low-lying

neighborhood.

Camaraderie and laughter

punctuated the sometimes

serious discussions of

environment and restoration

of New Orleans wetlands. A

few blamed the heat for the

inevitable water fight, caused

when a liner tarp had to be

rinsed and the hose went rogue.

Next stop was an office complex, where the

developer had decided a native landscaping would

afford a more environmentally friendly option.

BSA’s volunteers formed teams and spread out to

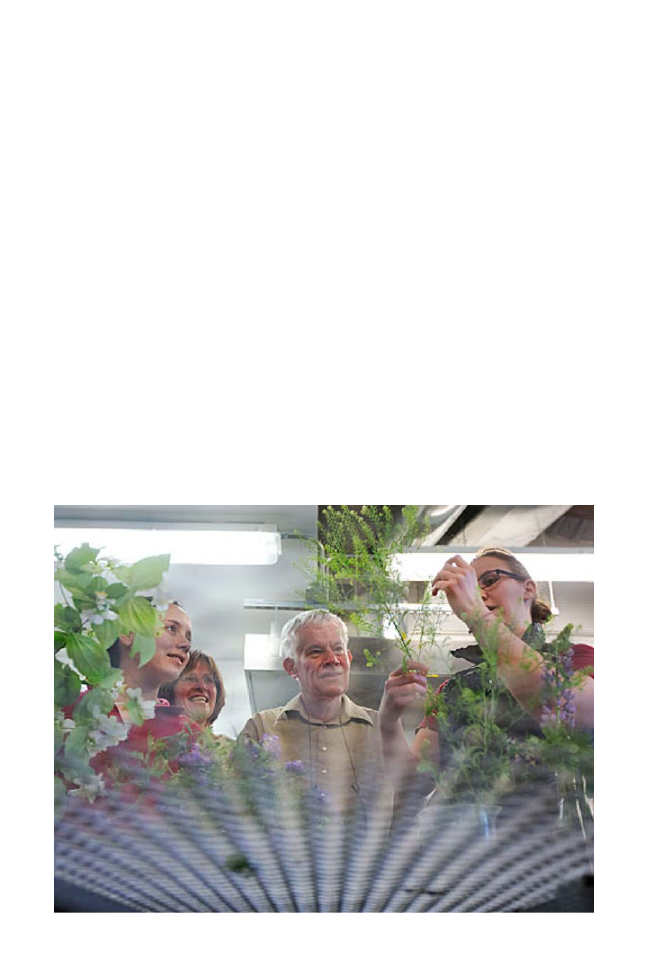

Seanna Walsh of the University of Hawaii mixes

soil during the Botany in Action project.

At an urban office complex where the native species

were used to landscape, the Botany in Action Team

went to work weeding and planting.

Part of the assignment was separating and replanting

some of the wetlands species, something the botanists

took on with smiles.

Toting blocks from an old seedbed to create a new

one called for some muscle.

89

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

accomplish the tasks laid out by Bayou Rebirth,

sharing the tools and supplies to get the needed end

results. As the heat of the New Orleans day grew,

the enthusiasm of the botanical volunteers never

waned for the task at hand. They moved gardens,

spread mulch, planted seedlings, all while learning

about the site’s solar re-circulated filters and rain

water systems.

Not only did they see it as a way to grow knowledge

about species of plants they had not seen before,

they saw it as a way to grow friendships among

kindred spirits who care not only about botanical

science but also about the world community.

Holding up muddy hands and wearing a big

smile, one participant said, “I like to help out, and

I’m learning about plants and digging in the dirt.

It’s fun!”

Another added, “It is fun, but it’s also the

right thing to do. And we learn about another

community, its issues and the botanical aspect of it.”

So, in the end, it’s all about community and

making that community better. And, that, the

botanists will tell you, is just plain fun.

-Story and Pictures by Janice Dahl, Great Story!

Taking a close look at a tiny weed, you never stop

learning, even after hours of labor during the Botany

in Action project.

Bayou Rebirth’s mission focuses on restoring Louisiana’s

wetlands, and who’s history dates back to 2007. Bayou Rebirth

has a dedicated staff, relationships with a wide variety of sponsors

and partnerships, and a dedicated Board of Directors all working

towards preserving and restoring Louisiana’s wetlands. See more at:

http://www.bayourebirth.org/about-us/#sthash.cIYj05qH.dpuf

In an effort to increase public awareness of coastal land loss and

the need for urban resilience to climate change impacts, Bayou

Rebirth seeks to bring together, educate, and empower residents

of and visitors to South Louisiana through hands-on wetlands

restoration and stewardship projects. - See more at: http://www.

bayourebirth.org/about-us/mission/#sthash.n0CfPhj3.dpuf

Botany 2013 is proud of the volunteers that helped and donated their

time to this very worthy cause.

90

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

New and Ongoing Society

Efforts

PlantED Digital Library

Do you have a resource for teaching or learning

botany to share? Resource Editors J. Phil Gibson

and Stokes Baker are pleased to announce a call

for submissions to the BSA’s digital library. Inquiry

activities, data sets, syllabi and images are only a

few of the resource types welcome.

PlantED, the BSA’s new resource portal, is run

in conjunction with companion portals of the

Ecological Society of America, the Society for

Economic Botany, and the Society for the Study

of Evolution. Peer-reviewed resources in PlantED

will be searchable across these four portals and

included in the National Digital Science Library.

Your resource supporting botanical education

could reach a wide audience.

If you have resource to contribute, we’re here

to help you share it. Please visit

http://planted.

botany.org

.

PlantingScience

As PlantingScience comes to the end of its first

(but we anticipate not its last) major grant, we are

taking stock of impacts and lessons learned. In

early planning meetings, the number of scientists

willing to volunteer was anticipated to be a potential

limiting factor for the project. How exciting it is to

report that was a faulty assumption.

The number of scientists offering their time

and expertise as online mentors has only grown

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Claire

Hemingway, BSA Education Director, at chemingway@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org.

across the years—now over 800 scientists from

diverse career stages and work places. New

mentors continue to join the effort to enhance the

way secondary school students and their teachers

experience science. As important as recruiting new

mentors, there is long-lived commitment on the

part of many mentors. Of those scientists who have

mentored two or more sessions, a phenomenal 6%

have mentored 10+ sessions—that’s lasting power

of 5+ years!

In addition to the opportunity to volunteer as a

mentor in any session that fits a scientist’s schedule,

the program has offered a special opportunity for

graduate students and post-doctoral researchers to

make a year-long commitment as a member of the

Master Plant Science Team (MPST). Since 2006,

the Botanical Society of America and the American

Society of Plant Biologists have sponsored 127

individuals; the Ecological Society of America

starts sponsorship this year. Nine MPST members

have served 3+ years—that’s significant mentoring

experience in early career development!

As scientists concerned with the state of science

education, you have shown great dedication. You

have also demonstrated skill in helping novice

science learners see how science works. In

analyzing 170 mentor dialogs between scientists

and student teams, we found that mentors promote

the idea of scientific community, acculturate and

welcome students to it, seek to broker relationships

and negotiate expectations for interactions with

student teams, and encourage students to connect

ideas about science content and process when

asking about student ideas (Hemingway and

Adams, 2013).

91

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Our hearty thanks to each and every one who has volunteered as

a PlantingScience mentor and served as an Master Plant Science

Team member thus far. In our effort to recognize your efforts,

names in the illustrations are weighted by the

number of sessions participated.

Our Hats off to you!

92

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Thank you to the Master

Plant Science Teams

Thanks to the 2012-2013 Master Plant Science

Team Members, Mon-Ray Shao, Lisa Kanizay,

Christine Palmer, Lina Castano-Duque, Molly

Hanlon, Mohammad Salehin, Elena Batista

Fontenot, Kranthi Mandadi, Mitchell Harkenrider,

Jennifer Lind.

Our thanks to the 2013-2013 Master Plant

Science Team. The BSA sponsored: Ben Gahagen,

Katherine Geist, Klara Scharnagl, Sampurna Sattar,

Katie Clark, Evelyn Williams, Angela Rein, Marites

Sales, Katie Becklin, Steven Callen, Alan Bowsher,

Elizabeth Georgian, Wesley T Beaulieu, Max Jones,

Bryan T. Drew, Chris Doffitt, Rhiannon Peery,

Rupesh Kariyat. The ASPB sponsored: Susan Bush,

Mon-Ray Shao, Lisa Kanizay, Christine Palmer,

Lina Castano-Duque, Molly Hanlon, Mohammad

Salehin, Elena Batista Fontenot, Kranthi Mandadi,

Mitchell Harkenrider, Jennifer Lind

Education in Action at

Botany 2013

A Few of the Teaching Session

and Poster Highlights

How effective is PowerPoint as an instructional

delivery method? How severe is “Plant Blindness”

among undergraduate students? What goes into

developing a general plant biology lab for distance

education? How can you make fake barf for a

forensic botany case study? These are some of the

questions addressed in talks and posters presented

this year at the Teaching Section.

Links to a few resources

mentioned in talks and posters:

Secondary Growth Animation—This animation

provides cellular, tissue, cross-section, and

macroscopic views across five seasons of grow.

Hide or show legends.

http://go.ncsu.edu/secondarygrowth

Cornell University Plant Anatomy Collection—

This searchable online slide collection of over 8,800

anatomical slides of a wide array of plant parts is

available for both teaching and publication. Try the

online measurement tool.

http://cupac.bh.cornell.edu

Biology Teaching Assistant Project (BioTAP)—this

is a network of individuals interested in enhancing

biology graduate teaching assistant professional

development. Learn more.

http://www.bio.utk.edu/biotap/

Yes, Bobby, Evolution is Real

Symposium

If you missed the selection of interesting talks

in the symposium on teaching about evolution,

you can catch some of the news and excitement it

generated:

The Times Picayune covered the symposium.

http://www.nola.com/education/index.

ssf/2013/07/scientists_criticize_creationi.

ht m l ? ut m _ c ont e nt = bu f f e r 0 6 b 5 7 & ut m _

source=buffer&utm_medium=twitter&utm_

campaign=Buffer

Chris Martine blogged about it in the Huffington

Post.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dr-chris-

martine/the-day-that-botany-took-_b_3703257.

html

From Around the Nation

Art and Science Collaborations

in Ecological Reflections

Science is a way of knowing; art is a way of

knowing. When scientists, artists, and writers

come together to explore places of long-term

inquiry, their collaborations educate and inspire

broad audiences to build a deeper understanding of

the natural world. The Ecological Reflections is a

network of scientists, artist and writers that grew

out of the National Science Foundation (NSF)–

funded Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER)

program.

“How do we respond as change comes to

places we know and love?” is a central question

addressed in the Ecological Reflections, which

include creative writer/artist residencies,

interdisciplinary workshops, and K-12 projects.

Art-science collaborations at 11 LTER sites in the

continental US, Alaska, and French Polynesia are

being showcased at various locations. Attendees

at the 2013 or 2012 Ecological Society of America

meetings had the pleasure of seeing some featured

works first hand. An exhibit is also on display at

NSF.

http://www.ecologicalreflections.com

93

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Unleashing a Decade of

Innovation in Plant Science

“The nation is not prepared for future agricultural

challenges.” The final report of the Plant Science

Research Summit enlarges the vision and voice

to the national calls to action. Five interwoven

components are recommended to reimaging the

research enterprise to support the agriculture

sector: (1) increase the ability to predict plant

traits from plant genomes in diverse environments,

(2) assemble plant traits in different ways to solve

problems, (3) discover, catalog, and utilize plant-

derived chemicals, (4) enhance the ability to

find answers in a torrent of data, and (5) create a

T-training environment for plant science doctoral

students.

T-training means to add cross training that

prepares students for a wide variety of careers,

while retaining disciplinary apprenticeship in a

mentor’s laboratory and shortening time to degree.

The statistic that only one of six PhD biologists

becomes tenure-track faculty within five years

of obtaining their degrees is only one reason re-

imagining graduate training is recommended.

Read the full report:

h t t p : / / p l a n t s u m m i t . f i l e s . w o r d p r e s s .

com/2013/07/aspb-final-report-plant-summit-lo-

res-web-july-15-2013.pdf

The Power of Partnerships: A

Guide from the NSF Graduate Stem

Fellows in K12 (GK-12) Program

Although the GK-12 Program is no longer

ongoing, the community is encouraged to adopt

and expand on the GK-12 approach to foster

partnerships between universities and K-12

schools, with graduate fellows as key links. An

aim of the recently published guide is to support

adoption of best practices of this approach.

http://www.gk12.org/2013/06/10/the-power-

of-partnerships-a-guide-from-the-nsf-gk-12-

program/

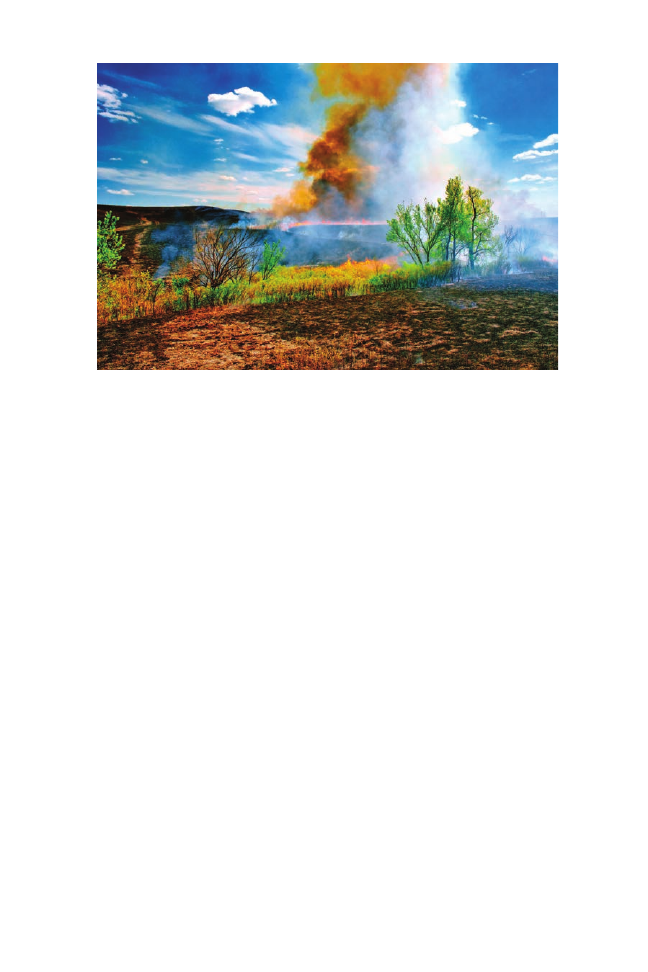

“Last Exit” by Edward Sturr, Konza Prairie.

94

Editor’s Choice Review

Engaging Students by Emphasiz-

ing Botanical Concepts Over Tech-

niques: Innovative Practical Exer-

cises Using Virtual Microscopy.

Bonser, S. P., P. de Permentier, J. Green, G. M.

Velan, P. Adam, and R. K. Kumar.

2013. Journal of Biological Education 47(2):

123-127.

Virtual microscopy, a technique developed in

implemented in many medical schools, allows

intro-level students to manipulate magnification

and scan images similarly to using a microscopy,

but without having to make adjustments of lighting

or focus. The authors present data that not only

do students prefer virtual slides, but in fact they

score statistically better on practical examinations

than students using traditional glass slides and

microscopes. So how important is the skill of being

able to effectively use a microscope? Or perhaps

more important, when should this skill be taught

to students?

Teaching Botanical Identification

to Adults: Experiences of the UK

Participatory Science Project ‘Open

Air Laboratories.’

Stagg, B. and M. Donkin. Journal of Biologi-

cal Education 47(2): 104-110.

Three different methods—dichotomous key,

mnemonic word association exercises, and pictorial

card games—were compared for learning plant

identification by a variety of adult participants

ranging from high school dropouts to college

graduates. There was no significant difference

between techniques for learning or motivation for

any of the groups.

A Forgotten Application of the

Starch Test.

Hartley, S. M. 2013. The American Biology

Teacher 75(6): 421-422.

In C4 plants, as explained in this article, only the

bundle sheath cells accumulate starch and stain

positively with IKI. It is a perfect inquiry lead-in to

C4 photosynthesis after students have worked with

C3 plants.

The Trouble with Chemical Energy:

Why Understanding Bond Ener-

gies Requires an Interdisciplinary

Systems Approach.

Cooper, M. M. and M. W. Klymkowsky. 2013.

CBE-Life Sciences Education 12: 306-312.

If you teach that “chemical bonds contain energy

that is then released as bonds break,” you have to

read this article. According to the authors, there

are three major reasons why students have difficulty

understanding energy: (1) biologists tend to talk

about chemical energy in a colloquial, everyday

sense, (2) physics and physical sciences explain

it from a macroscopic perspective (a ball rolling

down a hill), and (3) chemists fail to explicitly link

molecular with macroscopic energy ideas. The

authors walk through each of these difficulties and

present a model for integrating energy concepts

throughout the curriculum.

95

ANNOUNCEMENTS

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

BULLARD FELLOWSHIPS IN

FOREST RESEARCH

Each year Harvard University awards a limited

number of Bullard Fellowships to individuals in

biological, social, physical and political sciences to

promote advanced study, research or integration

of subjects pertaining to forested ecosystems. The

fellowships, which include stipends up to $40,000,

are intended to provide individuals in mid-career

with an opportunity to utilize the resources and to

interact with personnel in any department within

Harvard University in order to develop their own

scientific and professional growth. In recent years

Bullard Fellows have been associated with the

Harvard Forest, Department of Organismic and

Evolutionary Biology and the J. F. Kennedy School

of Government and have worked in areas of ecology,

forest management, policy and conservation.

Fellowships are available for periods ranging

from six months to one year after September 1.

Applications from international scientists, women

and minorities are encouraged. Fellowships are

not intended for graduate students or recent post-

doctoral candidates. Information and application

instructions are available on the Harvard Forest

web site (http://harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu).

Annual deadline for applications is February 1.

AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL

SOCIETY RESEARCH PROGRAMS

Information and application instructions for all

of the Society’s programs can be accessed at http://

www.amphilsoc.org. Click on the “Grants” tab at

the top of the homepage.

INFORMATION ABOUT ALL

PROGRAMS

Purpose, Scope

Awards are made for noncommercial research

only. The Society makes no grants for academic

study or classroom presentation, for travel to

conferences, for non-scholarly projects, for

assistance with translation, or for the preparation

of materials for use by students. The Society does

not pay overhead or indirect costs to any institution

or costs of publication.

Eligibility

Applicants may be citizens or residents of the

United States or American citizen residents abroad.

Foreign nationals whose research can only be

carried out in the United States are eligible. Grants

are made to individuals; institutions are not eligible

to apply. Requirements for each program vary.

BRIEF INFORMATION ABOUT

INDIVIDUAL PROGRAMS

Franklin Research Grants

Scope

This program of small grants to scholars is

intended to support the cost of research leading to

publication in all areas of knowledge. The Franklin

program is particularly designed to help meet the

cost of travel to libraries and archives for research

purposes; the purchase of microfilm, photocopies or

equivalent research materials; the costs associated

with fieldwork; or laboratory research expenses.

Eligibility

Applicants are expected to have a doctorate

or to have published work of doctoral character

and quality. Ph.D. candidates are not eligible to

96

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

Library Resident Research

Fellowships

Scope

The Library Resident Research fellowships

support research in the Society’s collections.

Eligibility

Applicants must demonstrate a need to work in

the Society’s collections for a minimum of 1 month

and a maximum of 3 months. Applicants in any

relevant field of scholarship may apply. Candidates

whose normal place of residence is farther away

than a 75-mile radius of Philadelphia will be given

some preference. Applicants do not need to hold

the doctorate, although Ph.D. candidates must have

passed their preliminary examinations.

Stipend

$2500 per month.

Deadline

March 1 (March 3 in 2014); notification in May.

Contact Information

Questions concerning the Franklin and the Lewis

and Clark programs should be directed to Linda

Musumeci, Director of Grants and Fellowships,

at LMusumeci@amphilsoc.org or 215-440-3429.

Questions concerning the Library Resident

Research Fellowships should be directed to

Earle Spamer, Library Programs Coordinator,

at libfellows@amphilsoc.org or 215-440-3443.

apply, but the Society is especially interested in

supporting the work of young scholars who have

recently received the doctorate.

Award

From $1000 to $6000.

Deadlines

October 1, December 1 (December 2 in 2013);

notification in January and March.

Lewis and Clark Fund for

Exploration and Field Research

Scope

The Lewis and Clark Fund encourages exploratory

field studies for the collection of specimens and

data and to provide the imaginative stimulus that

accompanies direct observation. Applications are

invited from disciplines with a large dependence

on field studies, such as archeology, anthropology,

biology, ecology, geography, geology, linguistics,

and paleontology, but grants will not be restricted

to these fields.

Eligibility

Grants will be available to doctoral students

who wish to participate in field studies for their

dissertations or for other purposes. Master’s

candidates, undergraduates, and postdoctoral

fellows are not eligible.

Award

Grants will depend on travel costs but will

ordinarily be in the range of several hundred dollars

to about $5000.

Deadline

February 1 (February 3 in 2014); notification in

May.

English - Spanish / Spanish –

English Dictionary of Botany

Now Available

By far the world’s largest, most accurate, and most

in-depth English-Spanish / Spanish-English work in

botany, by Kenneth Allen Hornak (Lexicographer):

a wealth of terms compiled from thousands of

botanical studies carried out by doctors in their

fields.

Both plant and tree species glossaries are English-

Latin-Spanish and Spanish-Latin-English, in

accordance with the International Code of Botanical

Nomenclature, and broken down by country.

97

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

No more paging through the incomplete, semi-

accurate lists in print or online; this work provides

authoritative clarity for student and professional

alike.

It covers all aspects of botany: Plant

biochemistry, plant species, tree species, plant

ecophysiology, paleobotany, plant morphology,

plant anatomy, taxonomy and classification,

horticulture, arboriculture, plant breeding and

genetics, palynology, pteridology, agrostology,

orchidology, and much more.

The publisher Editorial Castilla la Vieja has

announced a NEW LOWER PRICE of $89 for the

electronic version. Contact them at:

E-mail

: service(at)editorialcastilla(dot)com

Phone

: 908-399-6273

Mailing address: Editorial Castilla La Vieja, c/o

P.O. Box 1574, Havertown, PA 19083 USA

A learning gap is filled with

plants

Arboretum offers increasingly

rare course in their morphology

By Alvin Powell, Harvard Staff Writer

Sam Perez is searching for mutants. But to find

them, he has to know what normal looks like.

Perez was among a dozen top botany graduate

students and postdoctoral fellows who took

an intensive, two-week course in what may be

a vanishing discipline, plant morphology, at

the Arnold Arboretum this month.

The course, with funding from the National

Science Foundation and the Arnold Arboretum,

is modeled after intensive, high-level courses

in marine science offered by the Woods Hole

Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and

in molecular biology at the Cold Spring Harbor

Laboratory in New York, according to William

Friedman, arboretum director and Arnold

Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology.

The course is the first of what will become an annual

summer offering in plant organismic biology at the

Arboretum.

98

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

In between, they have three-hour lectures each

morning, followed by lunch, and three hours of

laboratory time each afternoon, with discussion

sessions, special lectures, and dinner mixed in.

Students also gain access to the Arboretum’s living

collection of more than 15,000 plants spread over

281 acres.

The intensive atmosphere is needed to cover a

large amount of ground, said Diggle, who teaches

plant morphology at the University of Colorado.

“As fast as I can talk, that’s what I can cover,” Diggle

said. “My feeling is this is a really fundamental area,

a common denominator for people working in

different areas. … As we’ve become more specialized

in knowledge, the commonality of the organisms is

missing, and I think science is suffering for it.”

Despite the heavy workload, participants aren’t

shying away from adding more of their own.

Though the course tries to give the students a

general knowledge of plant morphology and is

not focused on their specific research subjects, the

students asked early on whether they could present

their research to the group during lunch, one of the

few breaks in the day.

“The students are extremely good, extremely

motivated,” Endress said. “They work more than we

expect.”

For Kelsey Galimba, a doctoral student from

the University of Washington, the long hours

haven’t been too much to handle. Like Perez,

Galimba signed up after finding that gaps in her

knowledge of plant morphology were affecting her

research. “It’s not been nearly as hard as I thought

it would be. I don’t know if it’s because we have a

good group or because of the interesting material,

but we’ve all been fine with the hours.”

The intensity provides not just an opportunity

to cover a lot of ground, Diggle said, but also

allows participants to bond, providing the seeds,

hopefully, of an informal network that will be part

of the lasting effects of the experience.

“My adviser said, ‘Josh, go to this because you

don’t get instruction in plant morphology like this

anyplace else,’” said Josh Strable, a doctoral student

at Iowa State University. “If you’re accepted, it’ll be

something you’ll take with you for the rest of your

career.”

(Reprinted with permission of the Harvard Gazette.)

Plant morphology, which involves understanding

the genesis of a plant’s entire shape and structure,

has been taught less frequently in recent years,

shouldered aside by the increased emphasis on

genetics and understanding of how a plant’s DNA

affects its growth and appearance.

“There aren’t that many places where the study of

the whole organism is very prevalent. It’s not a big

part of the curriculum,” Friedman said. “Zoology,

botany, ichthyology, all the ‘-ologies’ have been on

the ropes across the world, not just in the U.S. And

as faculty who used to study morphology and whole

organisms were replaced by genomics people, we’ve

lost the ability to connect genes back to the biology

of the organisms themselves.”

The dazzling diversity of flowering plants poses

a special problem for budding botanists, since

particular flower parts, for example, can look quite

different in one species than in another. In addition,

the use of a very few specific plants as laboratory

models—akin to lab rats or fruit flies—has focused

what morphological teaching there is on just a

handful of species.

Young scientists like Perez have become adept at

using the powerful tools of genetics in their studies,

but some are finding that their lack of knowledge of

plant morphology hinders their work.

Perez, a Michigan State University doctoral

student who graduated from Harvard College

in 2011, is examining plant mutants, comparing

their genomes with normal plants to discover

which genes are responsible for the mutated trait

to better understand the genetics of the normal

trait. He’s finding, however, that to identify plants

with mutations, he needs a better understanding of

normal plant morphology.

“Plant morphology is important to me because

I’m studying the development of certain floral

structures, but I don’t have an understanding of

what goes into the development of actual flowers,”

Perez said.

The course, taught by Pamela Diggle, visiting

professor of organismic and evolutionary biology

from the University of Colorado, and Peter Endress,

professor emeritus of the University of Zurich, was

specifically designed to be an intensive experience

for participants, Diggle said.

Students are picked up each day at 8 a.m. from

their dormitory at Emmanuel College in Boston’s

Longwood area, and are dropped off after 9 p.m.

99

about plants to supplement preservice education,

removing barriers to growing plants in classrooms

and outdoors, and developing sequences of plant

activities that diversify students’ experiences as

they advance through the curriculum.

Keywords: curriculum; elementary education;

instruction; plants; teachers.

INTRODUCTION

While the last 100 years have significantly increased

scientific knowledge about plants, there seems

to have been a concomitant decrease in student

education about and interest in botany over the

same period. The percentage of high schools offering

botany classes has decreased from over 50% in the

early 1900s to less than 2% in the 1990s (Hershey,

1996). Less than 1% of all students entering college

indicate “botany” as their future major (Uno, 1994),

and fewer undergraduate institutions are offering

botany degrees (Drea, 2011). Both Wandersee

(1986) and Kinchin (1999) have documented that

K-12 students have less interest in studying about

plants compared to animals. Students are also

less likely to say that plants are alive as compared

to animals, and most students find assigning

specific names to plants to be particularly difficult

(Wood-Robinson, 1991; Inagaki and Hatano,

2002; Bebbington, 2005; Cooper, 2008; Patrick and

Tunnicliffe, 2011).

Misconceptions pertaining to plant

growth and reproduction are also common in students of

all ages (Simpson and Arnold, 1982; Barman et al., 2003;

Schussler and Winslow, 2007).

This lack of botanical

interest and knowledge should be of concern on

a planet where the survival of animals, including

humans, is dependent on the health and ecosystem

services of the green plants that are the foundation

of terrestrial life.

Many botanists and educators suggest that student

interest in plants has to be carefully fostered from

an early age because children are not as inherently

interested in plants as they are about animals.

Wandersee and Schussler (2001) have argued that

humans have a natural visual tendency to be “Plant

Blind.” Plant characteristics such as their lack of

movement and a face, their uniform color and

spatial grouping, and the fact that they are typically

not harmful result in humans discarding them

from their conscious attention. However, visual

Elementary botany: how teachers

in one school district teach about

plants

Melanie A. Link-Pérez

1

and Elisabeth E.

Schussler

2

1

Armstrong Atlantic State University, De-

partment of Biology, 11935 Abercorn Street,

Savannah, Georgia 31419

2

University of Tennessee, Department of

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, 569 Dab-

ney Hall, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996

Authors for correspondence: M.L.-P.

(eschussl@utk.edu); E.S. (eschussl@utk.edu)

DOI: 10.3732/psb.1300002

Submitted 4 January 2013.

Accepted 22 May 2013.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the

Committee for Faculty Research at Miami

University, Mr. Jeff Winslow for his support, and

the teachers who participated in this study. The

comments of two anonymous reviewers helped

improve the manuscript.

ABSTRACT

Students rarely know as much about plants

as animals. Some researchers attribute this to

deficiencies in formal education; however, little

has been documented about how K-12 teachers

approach teaching plant topics. We investigated

how elementary teachers in one school district

teach about plants. Thirteen K-5 teachers were

interviewed. Teachers expressed comfort teaching

about plants despite having little botanical training.

All used resources beyond the textbook and affiliated

activity kit, but activities and topics were repetitive.

Teachers said students loved growing plants, but

lack of adequate sunlight, water, and space made this

difficult. Most would like a garden or greenhouse

at school. Results suggest elementary botanical

education, at least in this school district, could be

improved by providing professional development

Reports

100

Plant Science Bulletin 59(3) 2013

attention to plants can be increased by educational

exposure to them. A nature study in Switzerland

showed that a relatively short educational program

(averaging 17 hours of instruction) on local flora

and fauna for 8- to 16-year-olds significantly

increased student knowledge and appreciation of

local plants (Lindemann-Matthies, 2005). Thus,

instruction about plants in formal education

settings should be a critical component of

fostering botanical interest and knowledge (Strgar,

2007; Fancovicova, 2011; Ju and Kim, 2011).

Botanists, however, have suggested that primary

and secondary school curricula and/or instruction

are not facilitating student learning about

plants. Evidence from student interviews found

that children say they learn more about the

names of plants at home (71%) than they do at

school (27%) (Tunnicliffe and Reiss, 2000). One

possibility for this lack of formal learning about

plants is deficiencies in curricula about plants.

For instance, Link-Pérez et al. (2010) found that

in two major publishing companies’ elementary

science textbooks, the photographs of animals were

captioned with specific names more than 80% of

the time (e.g., rhinoceros, five-lined skink), while

a third of the photographs of plants were captioned

with terms for plant parts (e.g., leaf), life form (e.g.,

tree), or simply “plant”. In the same two textbook

series, Schussler et al. (2010) found that the topics

presented about animals were more focused on

adaptations and whole-organism content while

information on plants focused mostly on parts and

growth. They also discovered that animal examples

were used almost twice as much as plant examples

to illustrate content in the textbook series. Overall,

these textbooks (which were the same ones used

by the teachers in the current study) exhibited

differences in the presentation of plant and animal

content that could help to explain deficiencies in

student understanding about plants, particularly

in comparison to their understanding of animals.

These challenges for botanical education are likely

compounded by federal accountability mandates in

recent years that emphasized a focus on language

arts and mathematics in primary grades, leaving

limited time for science instruction (Marx and

Harris, 2006; Griffith and Scharmann, 2008).

On the other hand, curriculum is only one aspect

of the classroom. Ultimately, it is the teachers

themselves who determine what actually occurs

in the classroom setting. Even the best botany

curriculum in the world is useless if teachers

choose not to use it, as pointed out by Hershey