P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

Winter 2012 Volume 58 Number 4

In This Issue..............

Honoring Walter Hodges......p. 164

Don’t miss Botany 2013 Field Trips....p. 148

Thank for your generous support......p. 146

what can you contribute?

APPS

to be launched January 2013

From the Editor

Winter 2012 Volume 58 Number 4

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 58

Root Gorelick

(2012)

Department of Biology &

School of Mathematics &

Statistics

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler

(2013)

Department of Ecology &

Evolutionary Biology

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-1610

eschussl@utk.edu

Christopher Martine

(2014)

Department of Biology

Bucknell University

Lewisburg, PA 17837

c

hris.martine@bucknell.edu

Carolyn M. Wetzel

(2015)

Department of Biological Sci-

ences & Biochemistry Program

Smith College

Northampton, MA 01063

Tel. 413/585-3687

-Marsh

Lindsey K. Tuominen

(2016)

Warnell School of Forestry &

Natural Resources

The University of Georgia

Athens, GA 30605

lktuomin@uga.edu

For the past few years I’ve been working on a

project to interpret the history of botanical education

in this country. One of the themes that becomes

increasingly clear in the twentieth century is that

individual botanists and small groups of botanists have

consistently gone through phases of “reinventing the

wheel.” Virtually all of the pedagogical “innovations”

that you could list today have been tried in the

past—but they haven’t “stuck”! I hope to address

some of the reasons why in future issues of PSB and

in a final presentation at the 2013 annual meeting in

New Orleans. But let me jump ahead quickly to the

present. There is one major difference between all of

the previous cycles of attempting to improve science

education and the one we are currently in. Today it’s

not just a few individuals, or a single organization,

that is taking the lead. Instead, we have a confluence

of efforts, both top down and bottom up, that are all

reaching the same conclusions. The National Academy

of Sciences Board on Science Education, The College

Board’s Advanced Placement Biology Curriculum,

and the American Association for the Advancement

of Science all have developed guidelines for revising

the science curriculum – and they’re all basically alike.

Botanists, through BSA and ASPB, have had our input

into the latter: AAAS’s Vision and Change. Our final

effort is included in these pages. We encourage you

to reassess your own introductory courses with these

guidelines in mind.

Finally, you may notice something missing in this

issue. For the first time since I became editor, we are

not publishing a single feature article. In fact, only a

single article is currently in review, although I’ve been

assured that several are in preparation. I want to take

this opportunity to encourage you to consider sharing

some of your work with the membership and other

readers of these pages. Submit your articles at http://

www.editorialmanager.com/psb.

146

Society News

James D. Ackerman

Afiz Ajibade

Edith B. Allen

Nan Crystal Arens

Rafael E Arevalo Burbano

Joseph & Nancy Armstrong

Sidney R. Ash

Nina Lucille Baghai-Riding

Stokes S. Baker

Bruce G. Baldwin

Grant M. Barkley

Mary Barkworth

Karen Barnard

Ellen T. Bauder

Amy Berkov

Charles E. Blair

Linda M. Broadhurst

Luc Brouillet

Steven B Broyles

Leo P. Bruederle

Janelle M. Burke

Imre Matyas Buzgo

Melanie Byerley

Diane L. Byers

Aubrey Cahoon

Clyde L. Calvin

Andrea L. Case

Brenda B. Casper

Russell L. Chapman

William Cheadle

Gregory P Cheplick

Hong-Keun Choi

John Choinski

Lynn G. Clark

Jim Cohen

Margaret E Collinson

Paul L. Conant

Martha E. Cook

Todd J. Cooke

Janice Marie Coons

S. H. Costanza

Nancy Coutant

Nancy E. Cowden

William Louis Crepet

Wilson Crone

Mitchell Cruzan

Chicita F. Culberson

Theresa M. Culley

Peter S. Curtis

Edward J. Cushing

Stephen Darrel Davis

Carol Dawson

Ted Delevoryas

Darleen A. Demason

Nancy Dengler

Melanie L. Devore

Pamela Kathleen Diggle

Kevin W. Dougherty

Jennifer Doubt

Andrew Nicholas Doust

Rebecca Drenovsky

Leah S. Dudley

Bohdan Dziadyk

Susan E. Eichhorn

Wayne J. Elisens

Diane Marie Erwin

Frank W. Ewers

Lafayette Frederick

Vicki A. Funk

Candace Galen

Moira Galway

Maria A. Gandolfo

Janet L. Gehring

Jennifer Geiger

Lawrence J. Giles

Thomas J. Givnish

Daniel K. Gladish

Stefan Erwin Gleissberg

Martin C. Goffinet

Charles W. Good

Uromi Manage Goodale

Carol Goodwillie

Hazel J. Gordon

Linda Graham

Sean W. Graham

Brenda J. Grewell

Cecilia Greyson

Sincere thanks to all of our donors for their generous

support of our multiple sections, student awards and travel

funds, and the BSA Endowment

147

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

Judy Parrish

William J. Platt

Cyrille Prestianni

Katherine A. Preston

Robert A. Price

Thomas Ranker

Eric Ribbens

Steve Rice

Jennifer H. Richards

Ricarda Riina

Vanessa Lopes Rivera

Alison W. Roberts

Robert G. Ross

Thomas Lowell Rost

Carl Rothfels

Scott D. Russell

Peter Ryser

Ann Sakai & Stephen Weller

Carl D Schlichting

Andrew Schnabel

Edward L. Schneider

Eileen K. Schofield

Lisa M. Schultheis

Patricia Jean Schulz

James & Marilyn L. Seago

Elizabeth C. Seastrum

Joanne M. Sharpe

Michael Simpson

Lawrence & Judith E. Skog

Michelle Amber Smith

Selena Y. Smith

Allison Ann Snow

Douglas & Pamela Soltis

John R. Spence

Kelly P. Steele

James B. Stichka

Peter F. Straub

Takahide Kurosawa

Elizabeth P. Lacey

David W. Lee

Blanca R. Leon

Geoffrey Levin

Amy Litt

William Mclagan Malcolm

Greayer Mansfield-Jones

Brigitte Marazzi

Marilyn C. Marynick

Lucinda Ann Mcdade

David J. Mclaughlin

Dr. Manjari A. Mehta

Irving A. Mendelssohn

Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud

Helen J. Michaels

James E. Mickle

Charles N. Miller Jr

Brent Mishler

L Maynard Moe

Brenda Molano-Flores

Arlee M. Montalvo

Nancy Morin

Mark E. Mort

Lytton John Musselman

Joan E. Nester-Hudson

Trina L. Nicholson

Karl J. Niklas

Mart Nirzka

Harufumi Nishida

Eisho Nishino

Gretchen B. North

Sally L. Norton

Richard Nuss

Richard G. Olmstead

Jeffrey M. Osborn

Virgil T. Parker

Yaffa L. Grossman

Jocelyn Hall

Judith Hanks

Gary L. Hannan

Clare Ann Hasenkampf

Marsha & Christopher Haufler

Donna Hazelwood

Leo J. Hickey

Jason Hilton

Ann Hirsch & Stefan Kirchanski

Hans R. Hoester

Joseph Hogg

Noel & Patricia Holmgren

Kent E. Holsinger

Raymond W. Holton

Marcus Hooker

Harry & Celia T. Horner

Tom Horton

Carol L. Hotton

Shing-Fan Huang

Francis M. Hueber

Bonnie L. Isaac

Rachel Schmidt Jabaily

Anna L. Jacobsen

Claudia L. Jolls

Cynthia S. Jones

Tracy Lynn Kahn

Dorothy Kaplan

Lee B. Kass

Kathleen H. Keeler

Sterling C. Keeley

Amanda Kenney

Robert A Klips

Olga R. Kopp

Suzanne Koptur

Jean D. Kreizinger

148

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

Peter Wilf

Joseph H. Williams

Carol Wilson & Clyde Calvin

M. F. Wojciechowski

Eckhard Wollenweber

Richard Lee Wurdack

Atsushi Yabe

Jun Yokoyama

Elizabeth A. Zimmer

Wendy B .Zomlefer

Andrew Stuart

Marshall & Sara D Sundberg

Jennifer A. Tate

Thomas N. Taylor

Edith L. Taylor

Irene Terry

Barbara Thiers

Rahmona A. Thompson

Bruce H. Tiffney

Lindsey K. Tuominen

Lowell E. Urbatsch

Mario Vallejo Marin

Paul Leszek Vincent

Andrea Wakefield

Don Waller

Megan Ward

Linda E. Watson

Cherie L. R. Wetzel

Elisabeth Wheeler

Richard Whitkus

Alligator Bayou is easily accessible off I-12 at Prairieville, just south of Baton

Rouge on the way to New Orleans. A short distance from the landing the bayou

expands into Cypress flats where a few old-growth trees, and numerous stumps

from logged trees emerge from a mat of water hyacinth. Scenes like this occur

throughout South Louisiana - - be sure to sign up for one of the field trips associated

with the annual meeting next summer. (photo by Marsh Sundberg)

149

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

plants is becoming ever more critical – whether we

are discussing ecosystems, fields, or single cells – it

is useful to begin discussion of points we can agree

on and put forward to policy-makers.

-Elizabeth A. Kellogg, President, Botanical Society

of America

Plant Science Research

Summit Final Report

The final report of the Plant Science

Research Summit, held in September 2011,

is now available at http://botany.org/

plantsciencebulletin/121011_final_PSummit_

report.pdf. The summit was convened by the

American Society of Plant Biologists, with the goal

of defining a set of common priorities for plant

science research. As described in the Plant Science

Bulletin (2012, 58: 1), the summit was attended by

three representatives of the BSA, then President-

elect Elizabeth Kellogg, Past-president Judy Skog,

and Treasurer Amy Litt. This summary document

represents the input of a broad set of plant biologists,

although as noted in my original report in PSB,

ecology and evolutionary biology were somewhat

under-represented. In fairness to the organizers,

the people who they originally invited to represent

those disciplines were unable to attend.

It is worth reading the document as a statement

of broad goals shared by many plant biologists. The

hope is to use this in efforts to generate funding

for plant research in its broadest sense. The first

paragraph of the Executive Summary reads:

“Now, more than ever, it is vital to increase public

and private support for plant science research

and recognize the critical need to invest in its

future and embrace its potential.” The four grand

challenges identified by the document are (1)

Ensure nourishment for all, now and in the future;

(2) Protect, enhance and illuminate the benefits of

nature; (3) Fuel the future; and (4) Be sustainable.

Much of the sort of science described in this

report fits into the concept of “use-inspired basic

research,” outlined by Donald Stokes in the book

Pasteur’s Quadrant (Brookings Institution Press,

1997). He observes that the linear view of a

continuum between basic and applied research is

too constraining. Instead he suggests that some

scientific studies may search for fundamental

understanding of nature, while working in areas

that may ultimately benefit humans.

Like all policy documents, the summary report

represents the views of a particular set of people at a

particular time and is likely to lead to other similar

documents in the future that highlight different

aspects of the plant science agenda. It is perhaps

worth recalling Ben Franklin’s famous statement

“We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall

all hang separately.” At a time when knowledge of

ASPB – BSA Core Concepts and

Learning Objectives in Plant

Biology for Undergraduates

The American Association for the Advancement

of Science, National Science Foundation (NSF),

and other stakeholders recently published a call

to transform undergraduate biology education,

titled Vision and Change (http://visionandchange.

org/finalreport). Major themes of Vision and

Change include teaching core concepts and

competencies, focusing on student-centered

learning, promoting campus-wide commitments

to change, and engaging the biology community in

implementation of change. The American Society

of Plant Biologists (ASPB) and Botanical Society

of America (BSA) were among the first societies

to become involved in Vision and Change. NSF

awarded ASPB a grant to host a workshop in 2011

to gather feedback from plant biologists on how

to put the Vision and Change recommendations

into practice. One of the major concerns that

emerged from this workshop was the lack of a

defined set of core concepts in plant biology that

undergraduates should learn. This lack results in

underrepresentation or misrepresentation of plants

in undergraduate curricula and misunderstanding

about the importance and unique functions of plants

and their broader contributions to understanding

biology (e.g., plants “don’t do much”; plants are

“only important for photosynthesis”; plants are “not

interesting” to study).

To address these concerns, a working group of

ASPB and BSA members was assembled: Kathleen

Archer (Trinity College), Erin Dolan (University of

Georgia), Roger Hangarter (Indiana University),

Ken Keegstra (Michigan State University), Judith

Skog (George Mason University), Susan Singer

(Carleton College), Neelima Sinha (UC Davis),

Anne Sylvester (University of Wyoming), and Sue

Wick (University of Minnesota). The working

group was tasked with generating a set of core

concepts that:

• outline what undergraduate biology majors

should learn about plants;

150

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

• are consistent with themes from Vision and

Change and the new K-12 science education

framework;

• are the enduring, big ideas that explain what

makes plants distinct from other lineages of

organisms and describe the essential attributes

and life strategies of plants; and

• are broad and foundational in nature, and can

be divided further into multiple sub-concepts or

units of knowledge (e.g., learning objectives) that

are measurable.

For the purposes of this effort, plants were

defined as: eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms

with multicellular haploid and diploid stages in their

life cycle and protected diploid embryos.

ASPB and BSA members were invited to comment

on a draft of the core concepts, and their feedback

was used to generate the final version that follows.

The concepts are organized into the four life science

domains of the new framework for K-12 science

education developed by the National Academy of

Sciences Board on Science Education (http://www.

nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13165): (1) From

Molecules to Organisms: Structures and Processes,

(2) Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics,

(3) Heredity: Inheritance and Variation of Traits,

and (4) Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity.

Each set of concepts begins with a description

of the foundational knowledge in the domain.

Individual concepts are followed by sample learning

objectives: what students could do to demonstrate

their understanding of the concept. ASPB and

BSA leadership urge all who teach undergraduate

biology students to use this document as a guide for

curricular design and instruction.

1. From Molecules to Organisms: Structures

and Processes. Plants are living organisms that

grow, reproduce, and die. Plants and their parts are

made up of cells, which contain DNA and other

molecules that support plant functions. Plants are

attached and do not move from place to place to

acquire resources for survival. Plants grow toward

resources and have specific structures, called

chloroplasts, which carry out the reactions of

photosynthesis. Using the energy captured from

sunlight, plants produce molecules to support their

own growth and development. Plants also take up

water and inorganic nutrients from their terrestrial

or aquatic environment. Plant cells are bounded

by cell walls that are essential for growth and

development of the plant body.

1A: Structure and Function. How do structures

of plants enable life functions?

• Plants growing in various environments

have a diversity of structures for acquiring and

retaining water, exchanging gases, optimizing

photosynthesis, and supporting growth and

reproduction.

»Learning objective (LO): Compare and

contrast the structures by which vascular

and non-vascular plants obtain and

retain water, allow for gas exchange for

photosynthesis, and allow for long-distance

internal transport of water.

»LO: Map onto a phylogenetic tree of

plants the locations where innovations for

acquiring water, retaining water, exchanging

gases, upright stature, and reproduction in

the absence of swimming sperm arose.

»LO: Analyze structural and anatomical

features that optimize photosynthesis under

various environmental conditions such as

shading, water deficit, or high temperature.

• Plants have carbohydrate-based cell walls that

serve diverse functions.

»LO: Contrast the primary cell wall

component of plants, fungi, and bacteria.

»LO: Analyze the roles of cellulose and cell

wall matrix components in support, growth,

and cell-cell recognition as well as protection

against pathogens.

• Plants have specialized structures and systems

for defense against disease and predation.

»LO: Categorize defense mechanisms into

structural, constitutive biochemical, and

induced biochemical responses, evaluating

the cost and benefits of each.

• Plants have conducting tissues that transport

water, carbohydrates, and nutrients through

both passive and active mechanisms.

»LO: Compare and contrast the long-distance

transport of carbohydrates with that of water

and nutrients in a plant.

»LO: Diagram the pathway of carbohydrate

transport from a source to a sink, indicating

where active transport is required.

• Some plants and plant parts are able to move.

»LO: Categorize plant structures and their

151

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

particular features that facilitate dispersal of

the plant in the environment

»LO: Select a plant structure that is capable

of movement and analyze the features that

enable it to move.

1B: Growth and Development of Organisms.

How do plants grow and develop?

• Plants can reproduce sexually and asexually.

»LO: Categorize examples of asexual

reproduction based on the plant structures

involved.

»LO: Select a plant and diagram the

contributions of the gametophyte(s) to

sexual reproduction.

• Plants grow from single cells and retain

groups of undifferentiated and dividing cells

throughout their lives.

»LO: Support the claim that plants continue

to develop and differentiate new structures

after formation of a multicellular structure

by drawing and identifying regions of a plant

with persistent meristem activity.

»LO: Using examples, explain how shoots and

roots are repeatedly added to a plant through

meristem activity.

• Plant germ-line cells are established after

vegetative growth has started.

»LO: Explain when and where in the plant

meiosis occurs.

• The development of plant form is influenced

by external and internal cues.

»LO: Categorize internal and external cues

based on their effects on plant form.

»LO: Draw a diagram that represents the

effect of a specific wavelength of light

on plant form; include photoreceptors,

signal transduction, gene expression, and

morphological change in the diagram.

»LO: Draw a diagram that illustrates the effect

of gravity on plant form; include receptors,

signal transduction, gene expression, and

morphological change in the diagram.

»Plants produce and respond to hormones

that regulate growth and development.

»LO: Identify the categories of plant hormones

and provide examples of their effects on

growth and development.

»LO: Compare and contrast the production of

and response to a steroid hormone in a plant

and an animal.

• Cell expansion depends on biochemical and

biophysical processes, including wall loosening

and water pressure inside the cell.

»LO: Diagram how internal and external

cues integrate to contribute to mechanisms

of cell expansion.

1C: Organization of Matter and Energy Flow

in Organisms. How do plants obtain and use

matter and energy to live and grow?

• Plants capture light energy to assimilate

inorganic carbon dioxide into organic

compounds.

»LO: Create a diagram showing how

inorganic carbon is assimilated into organic

compounds in plants and overlay this with

the flow of energy through the plant.

• Plants take up and transport inorganic

materials from their surroundings.

»LO: Trace the path of movement of inorganic

nutrients from soil into the aboveground

part of the plant

»LO: Compare the roles of mycorrhizae and

root nodules in the uptake of inorganic

materials in plants.

»LO: Identify the two inorganic molecules

that are used to produce the majority of a

plant’s mass, and indicate their sources.

»LO: Explain how the availability of soil

microorganisms has supported or limited the

growth of economically important plants.

• Plants capture and use energy from sunlight.

Almost all other organisms on the planet eat

plants as a source of energy.

»LO: For a terrestrial ecosystem, analyze the

flow of energy among organisms.

• Plants photosynthesize and respire.

»LO: Explain why plants can grow in a closed

terrarium.

• Plants synthesize a wide variety of organic

compounds through diverse biochemical

pathways.

»LO: Choose a class of organic compounds

other than sugars and, in general terms,

explain the carbon and energy sources for

synthesis of these materials.

152

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

1D: Information Processing. How do plants

detect, process, and interpret information from

the environment?

• Plants detect and respond to physical and

biological cues in their environment, including

light, water, gravity, biochemical, and mechanical

stimuli.

»LO: Construct a representation of a

molecular receptor for a physical or

biological signal that clearly shows how the

signal is detected and how information is

conveyed from the receptor to the plant cell.

• Signals transmitted through a plant can

induce changes in gene expression, protein

activity, and protein turnover.

»LO: Compare and contrast a signaling

pathway that leads to the activation of a

cytosolic enzyme and a pathway leading to

changes in gene expression.

• Plants can respond to stimuli over a broad

range of time scales.

»LO: Choose a stimulus that has an immediate

response in a plant and a stimulus that

results in a response days or weeks later;

compare and contrast the information

processing in the two examples.

• Plants perceive and respond to each other and

to other organisms in their environment.

»LO: Diagram how a signal from a plant is

perceived and acted upon by another plant.

»LO: Compare and contrast how a plant

detects, processes, and interprets information

from an herbivore and a pathogen.

»LO: Provide examples of how herbivory

alters plant growth.

2. Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and

Dynamics. Ecosystems are communities

of organisms and their nonliving physical

environment. Ecosystems are defined by complex

hierarchical networks of interactions among

individuals and populations, as well as interactions

between organisms and their environment. All

organisms in an ecosystem are linked through

energy flow and cycles of water, carbon, nitrogen,

and soil minerals. Energy enters the ecosystem

mostly through photosynthesis and biomass

production by plants. Other organisms obtain

matter and energy from the plants. Decomposers

act on dead organic matter, releasing carbon back

to the atmosphere and facilitating nutrient cycling

by converting nutrients stored in dead biomass

back to forms that can be reused. Ecosystems are

dynamic and changes in biotic and abiotic factors

affect their stability and resilience. Humans are part

of the biotic community and are having rapid effects

on the biotic and abiotic aspects of ecosystems. In

many cases, humans are placing profound stresses

on the Earth’s overall ecosystem to a point that

ecosystem resilience, sustainability, and services are

a major focus of concern.

2A: Interdependent Relationships in

Ecosystems. How do plants interact with the living

and non-living environment?

• Plants are the primary food and oxygen

producers on Earth.

»LO: Compare the relative contributions of

plants and another photosynthetic organisms

like lichens or terrestrial algae to production

of food and oxygen on land.

• Plants are foundational to large ecosystems.

»LO: Evaluate the statement that plants are

the foundation of terrestrial ecosystems.

• Plants live in close association and interact

with other organisms, including other plants,

animals, fungi, and microorganisms.

»LO: Chose an example of an interaction

between a plant and another organism and

elaborate on the ways in which they interact

to the benefit of one or both organisms.

• Plants produce metabolites that affect other

organisms in ecosystems.

»LO: Choose a plant metabolite that affects

other organisms in the ecosystem and

explain the mechanism of the effect.

• Plants have changed and continue to change

Earth systems.

»LO: Evaluate the geological evidence that

plants contributed to glaciation (i.e., ice

ages).

»LO: Contrast the general properties of

plants, soil, and fauna on Earth at the time

that plants first colonized dry land with the

general properties of those organisms today.

»LO: Analyze the progression of changes in

plants and other organisms that occur after

a volcanic eruption or a major wildfire.

153

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

2B: Cycles of Matter and Energy Transfer in

Ecosystems. How do matter and energy move

through an ecosystem?

• Energy first enters ecosystems through

photosynthesis.

»LO: Evaluate the claim that energy first

enters the ecosystem through photosynthesis;

consider relative to chemosynthesis.

• Plants cycle oxygen and carbon dioxide

through photosynthesis and respiration.

»LO: Create a diagram that illustrates the

flow of oxygen and carbon dioxide through

photosynthesis and respiration in an

ecosystem.

• Plants cycle water in ecosystems through

photosynthesis, respiration, and transpiration.

»LO: Diagram the flow of water through an

ecosystem, incorporating photosynthesis,

respiration, and transpiration.

• Plants are central to the global carbon cycle

through photosynthesis.

»LO: Estimate the impact of a reforestation

and/or deforestation project of 1 million

hectares on the global carbon cycle.

• Plants participate in cycling nitrogen and

other nutrients.

»LO: Evaluate the nitrogen runoff into

watersheds from fields of nitrogen-fixing

crops versus fields of crops fertilized with

inorganic nitrogen.

2C: Ecosystem Dynamics, Functioning, and

Resilience. What happens to ecosystems when the

environment changes?

• Resilience of ecosystems depends on the

diversity of plant species.

»LO: Evaluate a current research paper

on how plant diversity affects ecosystem

resiliency after a disturbance.

• Plant populations are affected by

environmental changes, which alter ecosystems.

»LO: Consider a situation in which

population size or distribution of plants is

altered due to changes in climate, herbivore

populations, or invasive species, and predict

how this might affect other aspects of the

ecosystem.

3. Heredity: Inheritance and Variation of

Traits. Like other organisms, plants use DNA to

store genetic information and encode proteins,

which underlie the plant’s traits. Genes containing

DNA are organized into chromosomes and variants

of a given gene are called alleles. Each cell of a plant

contains a complete set of chromosomes, and the

same genetic information. As in other organisms,

plants transmit their genetic information from

parent to offspring, and from parent cell to

daughter cell. Inheritance of chromosomes from

parent to offspring explains why offspring have

traits that resemble the traits of their parents.

Mutations also cause variation in traits, which may

be harmful, neutral, or occasionally advantageous

for an individual.

3A: Variation of Traits. Why do individuals of

the same species vary in how they look and behave?

• Some natural populations of plants vary

widely in their phenotypes.

»LO: Identify a trait in a natural population of

plants, then collect and analyze phenotypic

data to determine how much the trait varies.

• Gene expression in plants is controlled by

genetic and environmental cues.

»LO: Analyze data from an online repository

of gene expression data to determine how

genetic differences or environmental cues

affect patterns of gene expression.

»LO: Design and conduct an experiment to

compare the expression of a gene of interest

under different environmental conditions.

»LO: Predict differences in gene expression in

mutant versus wild-type plants based on the

function of the gene.

3B: Inheritance of Traits. How are

characteristics of one generation related to the

previous generation?

• Plants can exist in haploid, diploid, and

polyploid states.

»LO: Design an experiment to determine the

ploidy of a plant tissue.

• Plants vary in their reproductive strategies.

Some self-fertilize, which can lead to offspring

that are genetically similar. Others have

mechanisms to ensure transfer of gametes

between different plants, which results in novel

genetic combinations.

154

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

»LO: Compare the genetic diversity of the

offspring of a plant that is reproducing

sexually versus asexually.

• Some plants can reproduce asexually,

producing offspring that are genetically identical

to each other and to the parent.

»LO: Compare the amount of genetic variation

in the offspring of a plant that self-fertilizes

and a plant that reproduces asexually.

• Some plants can hybridize within and

between species, which can result in novel traits

in the offspring.

»LO: Select an example of within species

hybridization (e.g., hybrid corn) and explain

why this can result in desirable agricultural

traits.

»LO: Diagram the flow of chromosomes from

plants of two different species that hybridize

to their offspring; construct an argument for

whether the offspring will reproduce.

»LO: Select a crop plant that is the result of

hybridization and subsequent polyploidy

(e.g., wheat or banana) and discuss how

polyploidy corresponds with important

agricultural traits.

4. Biological Evolution: Unity and Diversity.

Like all organisms, plants evolved from a single

celled organism and continue to evolve. The fossil

record of plants and many characteristics of living

plants provide strong evidence for evolution.

For example, plants use the same genetic code as

other organisms, providing evidence for a single

origin of life. Like other eukaryotic organisms,

plants have mitochondria and a nuclear envelope.

Plants also have chloroplasts, which resulted

from the endosymbiosis between a eukaryotic

cell and a photosynthetic bacterium. Diversity

of plants is especially critical in the face of global

climate change; plants and other photosynthetic

organisms have the capacity to reverse increases in

atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. The important

roles that plants play in human life as food, feed,

fuel, fiber, shelter, and pharmaceuticals have shaped

human civilization. The evolution of plants is

affected by humans, and affects humans.

4A: Evidence of Common Ancestry and

Diversity. What evidence shows that different

species are related?

• Plants have many genes and gene families in

common with all other organisms.

»LO: Using gene trees, support the argument

that plants have many genes and gene

families in common with all other organisms.

• All plants have chloroplasts with similar

structure and pigment composition; this is the

result of a single endosymbiotic event between a

eukaryotic cell and an ancestral cyanobacterium.

»LO: Analyze the structural and biochemical

evidence for the claim that a single

endosymbiotic event between a eukaryotic

cell and a cyanobacterium was ancestral to

all chloroplasts, including chloroplasts in

algal groups.

»LO: Formulate an evolutionary hypothesis

that accounts for the both the similarities

and differences among the chloroplasts of red

algae, brown algae, green algae, and land

plants, including differences in the number

of membranes.

• Plants have multicellular haploid and

multicellular diploid stages in their life cycles.

»LO: Draw a generic plant life cycle indicating

the role of meiosis and mitosis in establishing

multicellular haploid and multicellular

diploid stages.

»LO: Contrast the relative size of the

multicellular haploid stage in mosses, ferns,

and angiosperms.

• DNA sequences have helped establish the

relationships among major plant clades and

between plants and other organisms.

»LO: Use a computational phylogenetic tool

and DNA sequences of one or more genes to

predict the evolutionary relationships among

major plant clades or between plants and

other organisms.

4B: Natural Selection. How does variation

among plants affect survival and reproduction?

• Diversity of organisms at the chromosome

and gene level can be generated in several

ways, including recombination, mutation,

hybridization, and polyploidy, resulting in

the variation underlying evolution by natural

selection.

»LO: Compare the relative contributions of

recombination, mutation, hybridization,

and polyploidy to plant diversity.

155

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

»LO: Explain the biological constraints for

hybridization and polyploidy to successfully

increase plant diversity.

• Diversity among plants may be influenced by

factors such as epigenetics (i.e., structural rather

than sequence level changes in DNA) that affect

the way genes are expressed.

»LO: Explain how epigenetic phenomena

such as DNA methylation and histone

modification lead to phenotypic variation

among plants that are otherwise genetically

identical.

• Some plant species can survive a diverse and

changing environment. Others cannot, which

results in their extinction.

»LO: For various species that exhibit a range

of diversity, predict some possible outcomes

of expansion of their distribution due to

climate change.

»LO: If a new pathogen or herbivore is

introduced, predict possible outcomes for a

plant species, relative to its diversity.

4C: Adaptation. How does the environment

influence populations of plants over multiple

generations?

• Adaptation of plants to a variety of

environments on Earth has resulted in a

great diversity of structures and physiological

processes.

»LO: Categorize symbiotic relationships that

have adapted plants to life in a terrestrial

environment.

»LO: Compare strategies that have evolved

for population migration and dispersal

in mosses, ferns, gymnosperms, and

angiosperms.

»LO: Select and evaluate an adaptation in

plants for retaining water while facilitating

gas exchange.

»LO: For an aquatic plant, select, and evaluate

an adaptation for retaining gases needed for

photosynthesis.

»LO: Compare structures and their

modifications in desert plants from the

southwestern U.S. and South Africa.

4D: Biodiversity and Humans. What is

biodiversity, how do humans affect it, and how

does it affect humans?

• Diversity of plant species is important for the

long-term health of an ecosystem.

»LO: Analyze data from a recent paper on

ecosystem biodiversity and evaluate the

authors’ conclusions.

• Human activity has affected global plant

diversity, especially through the alteration of

habitats.

»LO: Using Long Term Ecological Research

(LTER) data sets, examine historical and

current biodiversity data for a particular

region and illustrate how the physical

environment and biodiversity have changed

as a result of human activity.

• Human selection has affected almost every

aspect of crop plants, including their structure,

reproduction, genetics, and adaptation.

»LO: For a given crop plant (corn, Brassica,

wheat, soy, potato, tomato, bean, banana,

etc.), compare its structure, reproduction,

genetics, and adaptation relative to its wild

ancestors.

»LO: Select a crop plant (e.g., corn, rice,

potato) and trace the evolutionary changes

that occurred through human domestication

of the wild relative.

»Agriculture shapes human populations,

including their size, distribution, and

cultures.

»LO: Compare the size, distribution, and

culture of a human population before and

during the introduction of agriculture.

»LO: Compare the size, distribution, and

culture of a human population as agriculture

became more sophisticated after 1900.

156

BSA Science Education

News and Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Claire

Hemingway, BSA Education Director, at chemingway@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at

psb@botany.org.

Cross-Organization

Connections and Education

Opportunities

In this issue, we highlight a variety of efforts and

opportunities to advance education reform on the

national level. It is exciting to see involvement of

BSA members integral to many of these current

collaborations — thank you for your important

contributions. A number of the national initiatives

address the Vision and Change call to action

to transform undergraduate biology education

(http://visionandchange.org). Other efforts aim to

provide teaching and learning resources or to tackle

issues that have come to the attention of the biology

education community.

These education efforts will continue to be all the

richer with BSA members adding their botanical

education expertise! If you would like more

information about these, get in touch. Please also

let us know about the initiatives you are involved in

so we can share this information with the broader

community.

Digital Resource Discovery

and Life Discovery Conference

Collaboration

The Digital Resource Discovery Grant is a

collaboration among the Ecological Society of

America, Botanical Society of America, Society for

the Study of Evolution, Society for Economic Botany,

and other professional societies to support high-

quality resources in ecology, evolution, and plant

sciences. The inaugural conference Life Discovery

– Doing Science Education Conference will be held

March 15-16, 2013 in St. Paul, Minneapolis (http://

www.esa.org/ldc/). Beverly Brown served on the

planning committee for the 2013 conference and

advisory panel for the collaborative grant. Phil

Gibson has been nominated to serve on the 2014

Life Discovery Conference planning committee.

Understanding Evolution

Invitation to Partner

An invitation to partner with Understanding

Evolution (UE) (www.evolution.berkeley.edu)

was positively received by the BSA Education

Committee in June. Through this partnership, BSA

members’ expertise on plant evolution can expand

and enhance the resources that target undergraduate

Introductory Biology. New resources include an

interactive syllabus connecting an evolutionary

perspective to each topic, a journal club toolkit for

accessing the literature, an evolution misconception

diagnostic, an Evo Gallery for student projects,

etc. BSA members can actively contribute to UE

by serving as an External Advisor responsible for

reviewing resources for both science and pedagogy,

evaluating resources, or submitting teaching

resources for possible inclusion in the UE database.

New Free Resource for

Case-Based Learning

Are you looking for real-world contexts for

your students to explore plant biology and its

interdisciplinary connections? An outcome of the

PlantIT Careers, Cases and Collaborations project

(DRL 0737669) is the e-book Problem Solving with

Plants: Cases for the Classroom. Download your

free e-book at: http://www.myplantit.org.

Problem Solving with Plants: Cases for the Class-

room contains 14 cases adaptable from middle

school to college classes and helps for teaching with

investigative cases.

157

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

Core Concepts in

Undergraduate Plant Biology

BSA members Judy Skog and Susan Singer

joined with education leaders in the American

Society of Plant Biologists to draft core concepts in

undergraduate plant biology and circulated these

for community feedback. These core concepts will

be used to guide learning objectives for 200-level

plant biology units within the HHMI-funded

CourseSource initiative, which will be created by

partnerships with the National Academies Summer

Institutes and professional societies and made

available through a digital repository.

American Institute for

Biological Sciences (AIBS) and

Partner Activities

The American Institute of Biological Sciences

(AIBS), including board member Judy Skog and

AIBS education committee chair Muriel Poston,

is tackling the issue of credentialing faculty that

was raised this summer (e.g., someone with

a PhD in botany is not considered qualified

to teach introductory biology). AIBS will be

developing a position statement, and president of

HAPS Dee Silverthorn is also working with other

societies to develop guidelines for accrediting

organizations. We’ll continue to keep you informed

of developments on this important issue.

The AIBS Education Committee

is exploring the

feasibility of developing an initiative that would

support biology/life sciences department leaders.

Presentations and posters from the Introductory

Biology Project Summer Conference, led by

Gordon Uno, are now online at http://ibp.ou.edu.

Beth Schussler, Marsh Sundberg, and Susan

Singer were among the presenters. Several action

items emerged from the sessions on the role of

professional societies and introductory biology. A

group will be getting together to write an article

that features the many different successful models

to promote education within specific scientific

societies and ways that education organizations

can work with scientific societies. Two-year faculty

would like to be able to more easily become involved

in professional societies, and encouraged societies

to consider new ways of welcoming them into their

communities. There was a call for the development

of a common statement on the importance of

introductory biology.

The PULSE Vision and Change Fellows were

announced in early September. Susan Singer is a

PULSE mentor in this joint effort by NSF, HHMI,

and NIH to support Leadership Fellows. PULSE

welcomes community involvement to help develop

and implement systemic change in undergraduate

life science education (http://pulsecommunity.org).

The AIBS is participating in an initiative

funded by the U.S. Department of Education to

address the big sustainability questions in our

classrooms (understanding and engaging in

problem solving around societal issues such as

access to food and water, poverty reduction, and

cleaner energy supplies). More information about

this “Sustainability Improves Student Learning in

STEM” initiative is online: http://www.aacu.org/

pkal/disciplinarysocietypartnerships/sisl/index.

cfm.

Are you helping to educate for a more sustainable

future? Help impact hundreds of thousands of

students by infusing sustainability into textbooks

from major publishers and get paid for your

efforts. Textbook publishers have seen the demand

from educators and students for sustainability-

related materials in our discipline. We have

been asked by major textbook publishers (e.g.,

Cengage and McGraw-Hill) to gather names of

potential reviewers who can receive remuneration

for suggesting ideas about how to educate for a

sustainable future. These ideas will be used as

examples and themes in their textbook revisions.

If you are interested in educating for a sustainable

future by serving as a reviewer or subject matter

expert, please fill out a survey at https://www.

surveymonkey.com/s/JGN89ZD.

For more information contact Susan Musante at

smusante@aibs.org.

BSA at National Association

of Biology Teachers

A number of BSA members presented at

the recent NABT Professional Development

Conference in Dallas, TX. Gordon Uno led

sessions in an AP Biology Symposium. Stephen

Saupe presented a poster on using leaf morphology

to measure mean annual temperature in the 4-year

college poster session. Susan Singer and Gordon

Uno will present in the 2012 NABT Faculty

Professional Development Summit. Stanley Rice

presented on root foraging investigations for

classrooms. Gordon Uno and Marsh Sundberg

158

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

led a special Saturday workshop on Planting

Inquiry in Science Classrooms. In association with

the NABT meeting, a PlantingScience Focus Group

meeting of teachers and mentors was held to gain

stakeholder input.

The new student roadmap through a science project

planned for the revised PlantingScience website will

have helps for science practices doing science, record-

ing ideas in notebooks and sketches, presenting sci-

ence, and talking science. A graphic will be associated

with each main support, such as this one for Arguing

the Evidence.

PlantingScience Successes

and Next Steps

PlantingScience is in high gear reviewing lessons

learned from the DRK12 grant (DRL 0733280)

to build on successes and plan next steps. The

online platform is currently undergoing a complete

overhaul. Some of the new resources include a

student roadmap through a project and supports

for science practices in keeping with the Next

Generation Science Standards. An Inquiry Task

Force, including representatives from the American

Society of Plant Biologists, Ecological Society of

America, American Phytopathological Society,

was established in the spring as a mechanism for

partner societies to participate in new inquiry

development. For highlights of some successes

and collaborative efforts, see the American

Society for Plant Biologists’ September/October

2012 newsletter: http://newsletter.aspb.org/2012/

septoct12.pdf

Plant Blog on

Huffington Post

Chris Martine has taken his “Plants Are Cool,

Too!” efforts to the popular media site Huffington

Post. Don’t miss his blog:

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dr-chris-martine/

leaf-fossils-preserved-leaves_b_1967427.html

159

Editors Choice Reviews

Plant Reproduction & the Pollen

Tube Journey – How the Females

Lure the Males

Lorbiecke, René. 2012. The American Biology

Teacher 74(8): 575-580.

Many of us have had students germinate pollen to

observe pollen tube growth on a slide, but Lorbiecke

has taken this one step further to demonstrate

chemotaxis as the pollen tube approaches an ovule

in this semi-in vivo assay. Rapid cycling Brassica

(Fast Plants) flowers are the research material and

the author provides detailed instructions, including

a diagrammatic flow-chart of the procedure, for

students to follow. Excellent macrophotographs

illustrate the results.

Do College Introductory Biology

Courses Increase Student Ecologi-

cal Literacy?

Cheruvelil, Kendra Spence and Xuemel Ye.

2012. Journal of College Science Teaching

42(2): 50-56.

Do prospective biology majors have greater

motivation for study and more positive perception

of environmental issues than non-majors? Yes. Do

they have better conceptual understanding? Not

so much. Are they more ecologically literate at the

end of the course? Not significantly. I’m sure these

results would be different in any of the courses we

teach. Or would they be? Actually, for most of us,

the results would probably be quite similar. Read

this article and set yourself a challenge.

160

Ethics CORE - Can You Help?

Together with the National Science Foundation,

Ethics CORE is working to give researchers and

professionals easier access to ethics information

through a new online portal. Ethics CORE (http://

nationalethicscenter.org) leverages its digital

platform to bring together a novel collection of

traditional library resources (e.g., encyclopedia,

research articles, etc.) with new media (e.g., blogs,

online communities and multimedia tools). The

goal is to create a virtual space where students,

faculty, researchers and practicing professionals

can seamlessly receive and share information on

everything from Authorship to Whistle-blowing.

As we seek to create a virtual hub for ethics

information, we would very much like to solicit

your input on the following questions:

1) What ethics resources (articles, documents,

books, websites, etc.) have been particularly useful

or relevant to researchers or practitioners in your

field?

2) Are there any case studies, particularly case

studies with positive outcomes, involving ethical

issues that might be interesting or useful to other

members of your discipline?

The Ethics CORE team can help you connect

with ethics resources useful to you. If you are

aware of any gaps in the ethics resources available

to members of your discipline, or if you need a

digital environment to serve a need particular

to your group, we would like to collaborate with

you. We also hope you consider Ethics CORE as a

mechanism for distributing your own related work.

-Megan Hayes Mahoney Visiting Digital Library

Research Librarian, Grainger Engineering Library,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Email:

mohayes2@illinois.edu

-Gene Amberg, Ph.D Collaborations Director,

National Center for Professional & Research Ethics,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Email:

gamberg@illinois.edu

BULLARD FELLOWSHIPS IN

FOREST RESEARCH

Each year Harvard University awards a limited

number of Bullard Fellowships to individuals in

biological, social, physical and political sciences to

promote advanced study, research or integration

of subjects pertaining to forested ecosystems.

The fellowships, which include stipends up to

$40,000, are intended to provide individuals in

mid-career with an opportunity to utilize the

resources and to interact with personnel in any

department within Harvard University in order

to develop their own scientific and professional

growth. In recent years Bullard Fellows have been

associated with the Harvard Forest, Department

of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and the

J. F. Kennedy School of Government and have

worked in areas of ecology, forest management,

policy and conservation. Fellowships are available

for periods ranging from six months to one year

after September 1. Applications from international

scientists, women and minorities are encouraged.

Fellowships are not intended for graduate students

or recent post-doctoral candidates. Information

and application instructions are available on the

Harvard Forest web site (http://harvardforest.fas.

harvard.edu). Annual deadline for applications is

February 1.

Position Available

Assistant/Associate/Full

Professor Bioeducation

Position # F99418

Job Summary:

The position is for an Assistant Professor (tenure

track), Associate Professor (tenure track or tenure

eligible), or Full Professor (tenure eligible) nine-

month appointment with a possible three months

of summer support for first three years. We are

seeking a colleague to contribute to our unique

PhD program in Biological Education. Preference

will not be given to a particular rank; all applicants

will be judged in accordance with their years of

experience. We seek a candidate with a Doctorate,

with research experience in teaching and learning

at the postsecondary level, and expertise in at least

one biology content area sufficient to add to and

ANNOUNCEMENTS

161

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

• Teaching experience at the university level

• Ability to teach other courses in areas of need

(e.g., molecular biology, general biology, etc.)

Salary and Benefits:

Salary and rank is commensurate with

qualifications and experience. Benefits available

include health, life, and dental insurance, as well as a

selection of several defined contribution retirement

programs. Dependents and spouses of UNC

employees who are employed as 0.5 FTE or above

are entitled to and eligible for Dependent Tuition

Grants. These tuition grants will cover in-state

tuition charges. Further requirements may exist.

Other benefits may be available based on position.

The position is a nine-month appointment with

a possible additional three months of summer

support provided by the Winchester Distinguished

Professorship Endowment for the first three years

to help the faculty member establish a productive

research agenda.

Requested Start Date: August 19, 2013

Application Materials, Contact,

and Application Deadline:

Screening of applications will begin on

December 3, 2012 and will continue until the

position is filled. Interested persons should apply

online at https://careers.unco.edu and select “View/

Apply for Faculty Positions” then choose “Assistant/

Associate/Full Professor – BioEducation.”

Application documents to be submitted online are

a letter of application/cover letter, a curriculum

vitae, and the names and contact information of at

least three references. In addition to the material

provided online, please send unofficial or official

copies of all undergraduate and graduate school

transcripts, a statement of research interests, a

statement of teaching philosophy, a list of courses

you would like to teach, and copies of published

original research articles to: Cynthia Budde, School

of Biological Sciences, Ross Hall, Box 92, University

of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO 80639. Tel:

970-351-2921. email: cynthia.budde@unco.edu.

For questions, contact Rob Reinsvold, Chair of the

search committee, at robert.reinsvold@unco.edu.

Additional Requirements:

Satisfactory completion of a background check,

educational check, and authorization to work in the

United States is required after a conditional offer of

collaborate with current expertise in the school.

The job duties include: teaching undergraduate

lectures and laboratories in biology content area

and graduate courses in Bioeducation and Biology;

training graduate students emphasizing biological

education research topics at the postsecondary

level of teaching and learning; providing service

for the school, college, university, and community;

conducting research in biological education;

applying for grants; and publishing original

research results.

Minimum Qualifications:

Doctorate (Ph.D. or Ed.D.) in Biology or

Science Education (or closely related field) with

demonstrated experience in Biological Education

Research:

• Evidence or potential for excellence in

teaching

• Demonstrated research and publication

record in the area of teaching and learning

• Potential or past success securing external

funding

• Ability to teach graduate courses in

bioeducation topics and educational research

techniques

• Ability to teach undergraduate courses in

some biology topic(s) that complements current

expertise in the school

• Potential or past experience in supervising

research students

Preferred Qualifications:

• Demonstrated pedagogical research at the

collegiate level of teaching and learning

• Ability to provide leadership with the

pedagogical aspect of our Ph.D. program in

Biological Education

162

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

employment has been made. Original transcripts

must be submitted at least one (1) month before the

start date.

Location and Environment:

The University of Northern Colorado is a

Doctoral/Research University enrolling 12,000+

graduate and undergraduate students. The

university, founded in 1889, is located in Greeley,

Colorado, which has a growing population of

90,000 and is situated an hour north of Denver

and 30 miles east of the Rocky Mountains. The

School of Biological Sciences currently has 18 full

time faculty members, 40 graduate students (MS,

MBS, and PhD), and 450 undergraduate majors.

The unique Ph.D. program in Biological Education

specializes in training biologists to be experts in

their disciplines and outstanding college biology

teachers. This degree program allows the student to

choose between an emphasis on the biology content

or an emphasis on biology pedagogy. Another

strength is our long tradition of cooperative

interactions between faculty of the Sciences and

Education. Further information about UNC and

the City of Greeley is available at http://www.unco.edu.

Additional Information:

This position is contingent on funding from the

Colorado State Legislature, approval by the Board of

Trustees, and subject to the policies and regulations

of the University of Northern Colorado. Federal

regulations require that the University retain all

documents submitted by applicants. Materials will

not be returned or copied for applicants.

The University of Northern Colorado is an equal

opportunity/affirmative action institution that

does not discriminate on the basis of race, color,

national origin, sex, age, disability, creed, religion,

sexual orientation or veteran status. For more

information or issues of equity or fairness or claims

of discrimination contact the UNC AA/EEO/Title

IX Officer at UNC Human Resource Services,

Campus Box 54, Carter Hall 2002, Greeley, CO

80639, or call 970-351-2718.

Angiosperm Origins—

Monocots First?

The origin of angiosperms continues to be an

unresolved issue, but has always been framed

within the paradigm of seed plant monophyly. This

is a parsimonious view, based on the improbability

that both seed-and-pollination and cambium-and-

woody growth are likely to have evolved more

than once. A Monocots-First scenario denies both

assumptions and claims that angiosperms arose

directly from a pteridophytic base and built their

seeds independently of all other living seed plants.

The cambium and woody growth developed later,

during the diversification of early dicots.

A Monocots-First scenario is both falsifiable

and has considerable explanatory power. The

similarity of early embryology in monocots and

pteridophytes is either a recent “reversion” or a deep

symplesiomorphy. Genomics of early development

should be able to verify which is correct. Because a

tubular cambium and woody growth came later—

in the diversification of early dicots—it can explain

“Darwin’s abominable mystery.” Woody growth

allowed more complex branching—a platform for

the evolution of smaller leaves that became both

petiolate and deciduous. These, in turn, fossilize

much more readily than herbaceous growth and

produced the “sudden appearance” that troubled

Darwin. Please take a look at this very different

Perspective: http://fieldmuseum.org/explore/

angiosperm-origins-monocots-first-scenario.

–William Burger, Department of Botany, Field Mu-

seum (e-mail: wburger@fieldmuseum.org)

Funding for Plant

Conservation and Native Plant

Materials Programs

Dear Plant Conservation Alliance Colleagues,

I am writing with some tentatively good news as

well as with a request.

As you know, the Bureau of Land Management

(BLM) has supported a modest native plant

materials program for a number of years. This

program, like many federal activities, has been

in jeopardy of reduced funding in the current

budgetary climate.

In 2011 we were successful in obtaining

language as part of the appropriations bill for the

163

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

Department of the Interior that instructed the BLM

to maintain a robust native plant program. This

language was secured, in part, through the efforts

of the Plant Conservation Alliance NGO members

who communicated its importance to their elected

officials.

Earlier this year, we had some additional success

when the report that accompanied the House

Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies

Appropriation Bill for FY 2013, included the

following language:

“Native Plant Program. The Committee is

supportive of the Bureau of Land Management’s

existing plant conservation and native plant

materials program and expects the Bureau to

continue the program through resources provided

under various accounts. The Committee directs

the threatened and endangered species account to

contribute to this program.”

These two sentences express the support of the

Committee for native plant programs and instruct

the Bureau of Land Management to maintain the

contribution to the program that comes through

the funding line item for the Threatened and

Endangered Species account. It is imperative that

elected officials, committee staff members and

agency personnel are repeatedly reminded of the

importance of funding for endangered and native

plant materials. If we don’t speak up for plants, no

one else will.

This brings me to my request: Please take a

minute to send a message to your elected officials

regarding the importance of protecting funding

for plant materials and native plant programs.

Following is some suggested text:

Dear _________:

On behalf of (organization), I am contacting you

to ask for your help in supporting funding for plant

conservation and native plant materials programs

through the Bureau of Land Management.

The United States has inherited a rich legacy of

biodiversity, with native plants delivering essential

ecosystem services such as waste purification,

climate modulation and habitat for myriad wildlife

and fish services across the United States. Native

plant communities are threatened by unsustainable

urban and rural development, expanding energy

production, the spread of invasive species, and

pollution. The United States needs to ensure that

native plant communities are protected and that

future generations benefit from the same legacy

that we have inherited.

The work of the Bureau of Land Management

(BLM) is critical to these efforts. Funding

provided through BLM is critical to these efforts.

Funding provided through BLM accounts for Land

Resources, Wildlife & Fisheries Management and

Threatened and Endangered Species supports work

on native plants, rare plants and addresses problems

posed by invasive plant species. These funds not

only protect biodiversity, but also contribute to

generating more science competency and green

jobs—new scientists, ecologists and land managers.

As Congress works to finalize the Department

of Interior’s 2013 funding, please ensure that

resources provided for plant activities is included

at no less that the FY12 level. We suggest including

the following language with the Bureau of Land

Management Appropriation:

“Native Plant Program. The Committee is

supportive of the Bureau of Land Management’s

existing plant conservation and native plant

materials program and expects the Bureau to

continue the program through resources provided

under various accounts. The Committee directs

the threatened and endangered species account to

contribute to this program.”

Contacting Congress:

You can find your Senators by visiting www.

senate.gov and following the “Find your Senators”

dropdown in the upper right corner. Or, if you

want to call and know the name of your Senator,

you can call the Capitol switchboard at 202-224-

3121 and ask to be connected to their office.

You can find your Representatives by visiting

www.house.gov and entering your service area zip

code(s) in the upper left corner. Or if you know

the name of your Representative, you can call the

Capitol switchboard at 202-224-3121 and ask to

be connected to his or her office. Once connected

to the Congressional office, please ask for the staff

handling appropriations for the Department of

Interior.

Sophia Siskel, President & CEO, Chicago Botanic

Garden, www.chicagobotanic.org. ssiskel@chica-

gobotanic.org, 847-835-8351

164

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

Hunt Institute Receives

National Film Preservation

Foundation Grant

(PITTSBURGH, PA)—Hunt Institute for

Botanical Documentation has been awarded

preservation project funding from the National

Film Preservation Foundation (NFPF) to preserve

Walter Hodge’s film of Peru in the 1940s. The award

will be used to clean, conserve and make both a film

copy for preservation and a digital copy for access.

Walter Henricks Hodge began his botanical

career in 1934 as a graduate teaching assistant at

Massachusetts State College. Eventually his resume

included time on the faculties of the University

of Massachusetts, the Universidad Nacional de

Colombia and Harvard University and service

in governmental and scientific organizations,

including the United States Department of

Agriculture and the National Science Foundation.

Hodge traveled extensively, including periods in

the West Indies, Peru, Colombia and Japan, which

provided him with ample opportunities to indulge

his interest in photography. His photographic work

illustrates practical and economic uses of plants

throughout the world and records not only a large

variety of plant species, but also informal portraits

of botanists he encountered in his travels. Hodge’s

still photographs have been published in various

United States Department of Agriculture bulletins,

National Geographic and the Christian Science

Monitor. From 1943 to 1945 he was a botanist for

the United States Office of Economic Warfare’s

Cinchona Mission in Lima, Peru, and the film we

will preserve is a result of this assignment.

The purpose of the Cinchona Mission was to

find reliable alternate sources of cinchona bark

for the wartime production of quinine. The

footage is a unique collection of material relating

not only to Hodge’s botanical mission, but also

to his interests in the local culture and customs

of Peru. Sequences include shots of local scenery

(including Macchu Picchu) and anthropologically

interesting material relating to native lives and

customs (including sequences in local street

markets and at a bullfight). Hodge’s wife Barbara

(1913–2009) traveled with him and can frequently

be seen in the footage, occasionally acting as a

model for close studies of textiles and jewelry.

Finally, Hodge did not neglect his central work

assignment; he included a sequence covering the

entire process of the harvesting and preparation

of cinchona bark. The film quality and color are

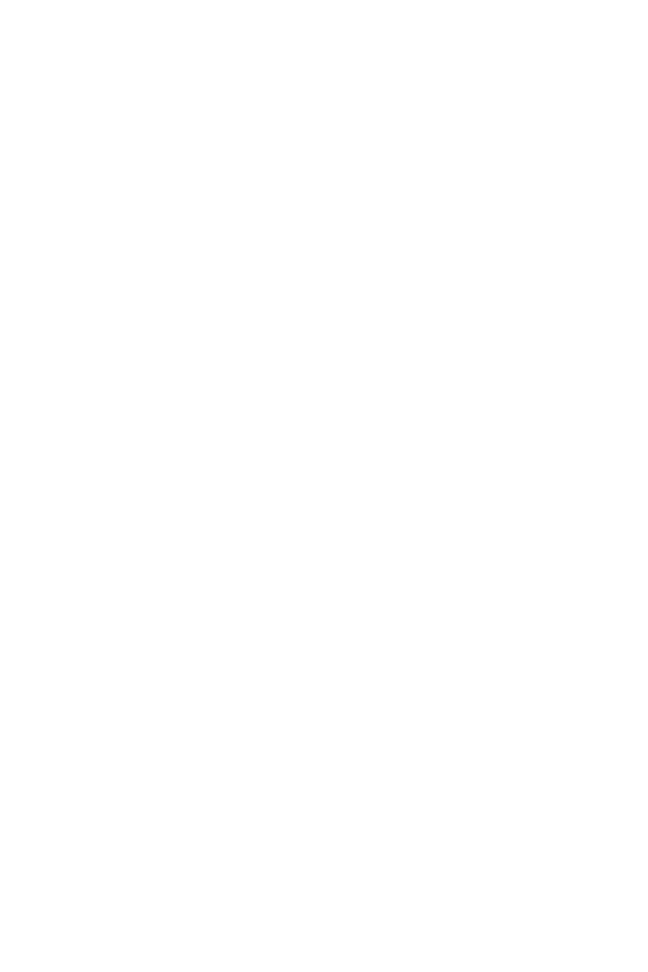

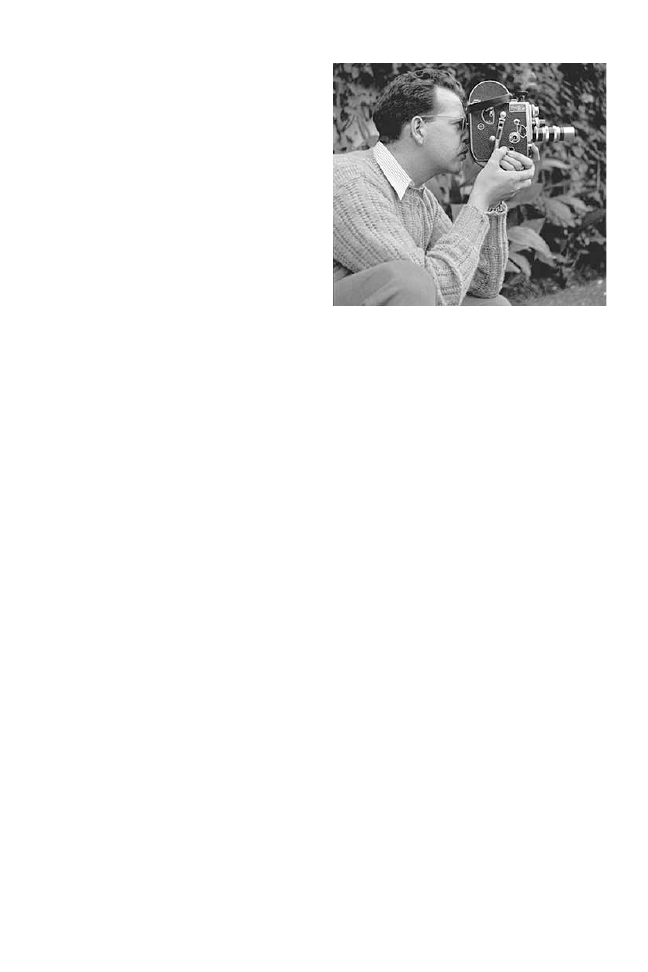

Walter Hendricks Hodge with his personal Cine-

Kodak Special 16mm camera, which was used

to create his film of Peru that will be preserved

with the grant funds, 1944, Miraflores, Lima

Peru, HI Archives portrait no. 94. Photo by

Barbara Taylor Hodge. (c 2012 Hunt Institute for

Botanical Documentation. All rights reserved)

excellent, and it is our feeling that this material will

interest botanists, anthropologists and historians.

Hunt Institute has had a long relationship with

Hodge, which began when Founding Director

George H. M. Lawrence (1910–1978) proposed that

Hodge take informal portraits of botanists. Over

the years Hodge has sold or donated thousands of

photographs to the Hunt Institute Archives. We

also hold 27 linear feet of Hodge’s professional and

personal correspondence and research.

The NFPF grant application process was

undertaken by Hunt Institute Archivist Angela L.

Todd with the assistance of Jeffrey A. Hinkelman,

video collection manager and course instructor

at Carnegie Mellon’s University Libraries, and

Hannah Rosen, preservation programs specialist at

Preservation Technologies in Cranberry Township,

Pennsylvania.

The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation,

a research division of Carnegie Mellon University,

specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of

plant science and serves the international scientific

community through research and documentation.

To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains

authoritative collections of books, plant images,

manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides

publications and other modes of information

service. The Institute meets the reference needs of

165

Plant Science Bulletin 58(4) 2012

botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists,

librarians, bibliographers and the public at large,

especially those concerned with any aspect of the

North American flora.

Hunt Institute was dedicated in 1961 as the

Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt Botanical Library,

an international center for bibliographical

research and service in the interests of botany

and horticulture, as well as a center for the study

of all aspects of the history of the plant sciences.

By 1971 the Library’s activities had so diversified

that the name was changed to Hunt Institute for

Botanical Documentation. Growth in collections

and research projects led to the establishment

of four programmatic departments: Archives,

Art, Bibliography and the Library. The current

collections include approximately 30,150 book and

serial titles; 29,000+ portraits; 29,270 watercolors,

drawings and prints; 243,000+ data files; and

2,000 autograph letters and manuscripts. The

Archives specializes in biographical information

about, portraits of and handwriting samples

from scientists, illustrators and all others in the

plant sciences. The Archives is a repository of

alternate resort and as such has collected over 300

institutional and individual archival collections

that may not have otherwise found an easy fit at

another institution. Including artworks dating from

the Renaissance, the Art Department’s collection

now focuses on contemporary botanical art and

illustration, where the coverage is unmatched. The

Art Department organizes and stages exhibitions,

including the triennial International Exhibition

of Botanical Art & Illustration. The Bibliography

Department maintains comprehensive data files on

the history and bibliography of botanical literature.

Known for its collection of historical works on

botany dating from the late 1400s to the present, the

Library’s collection focuses on the development of

botany as a science and also includes herbals (eight

are incunabula), gardening manuals and florilegia,

many of them pre-Linnaean. Modern taxonomic

monographs, floristic works and serials as well as

selected works in medical botany, economic botany,

landscape architecture and a number of other

plant-related topics are also represented.

Impulsive micromanagers

help plants to adapt, survive

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Soil microbes are

impulsive. So much so that they help plants face the

challenges of a rapidly changing climate.

Jen Lau and Jay Lennon, Michigan State University

biologists, studied how plants and microbes work

together to help plants survive the effects of global

changes, such as increased atmospheric CO

2

concentrations, warmer temperatures and altered

precipitation patterns. The results, appearing in the