P

LANT

S

CIENCE

Bulletin

Summer 2011 Volume 57 Number 2

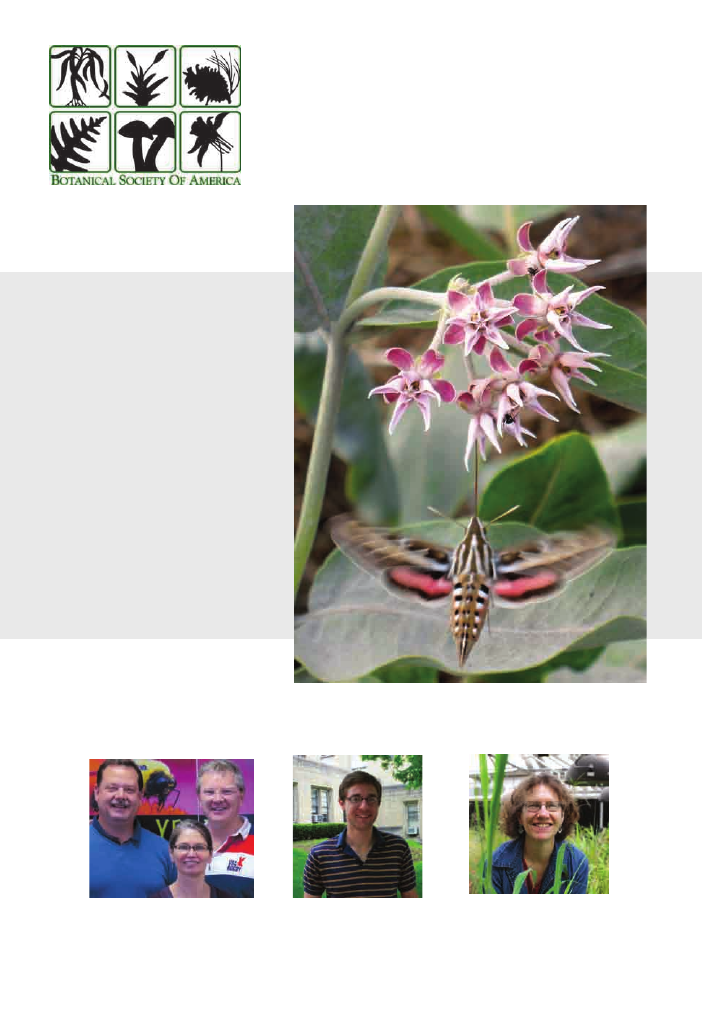

Matthew Koski wins the

J. S. Karling Student Research

Award. Congratulations

Winners .........................pg 42

BSA Election Results -

Congratulations all!..... Page 48

In This Issue..............

1st Place

Triarch Botanical Images

Student Travel Awards

James Riser

Washington State University

Showy milkweed and hawk

moth

PlantingScienceWins prestigious

SPORE Award from AAAS. Page 49

From the Editor

Summer 2011 Volume 57 Number 2

PLANT SCIENCE

BULLETIN

Editorial Committee

Volume 57

Jenny Archibald

(2011)

Department of Ecology

& Evolutionary Biology

The University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas 66045

jkarch@ku.edu

Root Gorelick

(2012)

Department of Biology &

School of Mathematics &

Statistics

Carleton University

Ottawa, Ontario

Canada, K1H 5N1

Root_Gorelick@carleton.ca

Elizabeth Schussler

(2013)

Department of Ecology &

Evolutionary Biology

University of Tennessee

Knoxville, TN 37996-1610

eschussl@utk.edu

Christopher Martine

Department of Biology

State University of New York

at Plattsburgh

Plattsburgh, NY 12901-2681

martinct@plattsburgh.edu

KUDOS to the PlantingScience team and a quartet

of outstanding botanists!

The PlantingScience website won the 2011 AAAS

SPORE Award, announced in the 25 March issue

of Science 331(6024): 1535-1536. See BSA Educa-

tion News and Notes, p. 49, for a brief description

and a link to the Science article. AAAS also recog-

nized three BSA members, Ned Friedman, Roger

Hangarter and Jonathan Wendel, as 2011 AAAS

Fellows and Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra was presented a

Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and

Engineers. See the Personalia section, pp. 54-5. for

more information about the awardees.

The main focus of this issue, however, is preparing

for the 2011 meeting in St. Louis where the theme

will be economic botany. To set the tone we feature

two articles with different approaches to the theme.

In Market Botany, Chris Martine provides a differ-

ent twist to engaging students in the role of plants

in modern life. The field trip he outlines is not the

usual anatomical/morphological foray to the pro-

duce section of the local supermarket. Instead it is

an analysis of product labels, not just food, with an

eye toward the taxonomic distribution of economi-

cally useful plants. An eye-opener to be sure!

Our second article is another in our recent series of

notable botanists, this time of one of the founders

of the field of ethnobotany, Richard Evans Schultes.

As author Rainer Bussman notes, for an ethnobota-

nist, talking about Schultes “is like talking about

god.” I am not one of the chosen, being a disciple

of Esau’s Anatomy, but Bussman’s interpretation of

the world according to Schultes certainly gave me a

greater appreciation

for this alternative

botanical perspec-

tive. I hope you

will find it just as

rewarding and that

you will “Meet me

in St. Louis.”

Carolyn M. Wetzel

Department of Biological

Sciences &Biochemistry

Program

Smith College

Northampton, MA 01063

Tel. 413/585-3687

-Marsh

41

Table of Contents

www.botanyconference.org

Register NOW....

Society News

Awards 2011 ...................................................................................................42

American Journal of Botany ............................................................................48

BSA Election Results ......................................................................................48

BSA Science Education News & Notes ..........................................................49

Editor’s Choice Reviews .................................................................................53

Personalia

White House award for Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra. ...................................................54

2011 AAAS Fellows. .......................................................................................55

Announcements

Coming up Short: Only 39 percent of North American endangered plant

species are protected in collections .................................................................56

The Catalina Island Conservancy Herbarium (CATA) – call for institutional

exchanges................................................ ........................................................57

Welcome to New BSA Staff Members ............................................................57

Meetings

Cycad 2011 Meeting in Shenzhen, China........................................................58

Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conference........................................59

Reports and Reviews

Market Botany: A plant biodiversity lab module. Christopher T. Martine. .....61

Reflections on the life and legacy of Richard Evans Schultes.

Rainer W. Bussmann .......................................................................................66

Books Reviewed ..............................................................................

70

Books Received ..............................................................................

75

To our Legacy Society Members ....................................................

77

BOTANY 2011 ................................................................................

80

42

Chi-Chih Wu

University of Colorado, Boulder

Advisor: Dr. Pamela Diggle - Botany 2011

presentation: “The impact of the lower genetic

relatedness of endosperm to its compatriot embryo

on maize seed development” Co-authors, Pamela

Diggle and William Friedman

The BSA Graduate Student

Research Awards

The BSA Graduate Student Research Awards

support graduate student research and are made

on the basis of research proposals and letters of

recommendations. Withing the award group is

the Karling Graduate Student Research Award.

This award was instituted by the Society in 1997

with funds derived through a generous gift from

the estate of the eminent mycologist, John Sidney

Karling (1897-1994), and supports and promotes

graduate student research in the botanical sciences.

The 2011 award recipients are:

J. S. Karling Graduate Student

Research Award

Matthew Koski

University of Pittsburgh

Advisor, Dr. Tia-Lynn Ashman, Breaking

boundaries of human visual bias: selection on

ultraviolet floral traits

BSA Graduate Student

Research Awards

Gerardo Acero-Gomez

University of Pittsburgh

Advisor, Dr. Tia-Lynn Ashman, Long live the

flower: increasing flower longevity and outcrossing

rate with increasing community diversity

Botanical Society of America

Awards 2011

We are pleased to announce the recipients of the 2011 awards provided by the Botanical Society of America.

Here we provide recognition for outstanding efforts and contributions to the science of botany. We thank

you for your support of these programs.

Darbaker Prize

The Darbaker Prize in Phycology is given each

year in memory of Dr. Leasure K. Darbaker. It

is presented to a resident of North America for

meritorious work in the study of microscopic

algae based on papers published in English by the

nominee during the last two full calendar years.

This year The Darbaker Award for meritorious

work on microscopic algae is presented to:

Dr. Sallie (Penny) Chisholm

Massachusetts Institute of

Technology

Vernon I. Cheadle Student

Travel Awards

(BSA in association with the Developmental and

Structural Section). This award was named in honor

of the memory and work of Dr. Vernon I. Cheadle.

Jessica Budke

University of Connecticut

Advisor: Dr. Cynthia S. Jones - Botany 2011

presentation: “Experimental Manipulation of the

Moss Calyptra: The effect of cuticle removal and

desiccation on sporophyte development in Funaria

hygrometrica.” Co-authors, Bernard Goffinet and

Cynthia Jones

David Duarte

Cal Poly Pomona

Advisor: Frank Ewers - Botany 2011 presentation:

“Seasonal changes in the vessel anatomy of adults and

resprouts of California black walnut trees following

wildfire” Co-authors, Edward Bobich, Sarah Pak,

Shawn Pham, Yasuhiro Utsumi and Frank Ewers

Ari Novy

Rutgers University

Advisor: Dr. Jean Marie Hartman - Botany 2011

presentation: “Rapid evolution of phenology during

invasion of the grass Microstegium vimineum in

North America.” Co-authors, Luke Flory and Jean

Marie Hartman

43

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Jose D. Zuniga

Claremont Graduate University

& Rancho Santa Ana Botanic

Garden

Advisor, Dr. Lucinda A. McDade, Systematics

and biogeography of Sabiaceae with emphasis on

Neotropical Meliosma.

The BSA Undergraduate

Student Research Awards

The BSA Undergraduate Student Research Awards

support undergarduate student research and are

made on the basis of research proposals and letters

of recommendation. The 2011 award recipients are:

Keri L Caudle

Fort Hays State University

Advisor, Dr. Brian R. Maricle

Jennifer Collins

SUNY Plattsburgh

Advisor, Dr. Christopher T. Martine

Jacqueline Rice

University of Florida

Advisor, Dr. Pamela Soltis

Eric Taber

Colgate University

Advisor, Dr. Eddie Watkins

Megan Ward

SUNY Plattsburgh

Advisor, Dr. Christopher T. Martine

Developmental & Structural

Section Student Travel Awards

Kelly Matsunaga

Humboldt State University

Advisor, Dr. Alexandru Tomescu

Botany 2011 presentation: “Nectary Structure of

Scoliopus bigelovii (Liliaceae).” Co-authors: Michael

R. Meslerand Alexandru Tomescu

Lavanya Challagundla

Mississippi State University

Advisor, Dr. Lisa Wallace, Evolution of B

chromosomes in the Genome of Xanthisma gracile

(Asteraceae)

Grant T. Godden

University of Florida

Advisor, Dr. Pamela S. Soltis, Out of the bushes

and into the trees: Alternative approaches to a

problematic mint phylogeny

Daniel M. Griffith

Wake Forest University

Advisor, Dr. T. Michael Anderson, Adaptive

Significance of Sodium and Grazing Tolerance in

Serengeti Grasses

Stephanie Pimm Lyon

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Advisor, Dr. Thomas J. Givnish, Systematics and

biogeography of Corybas (Orchidaceae)

Rhiannon Peery

University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign

Advisor, Dr. Stephen R. Downie, Understanding

genome interactions within the carrot family

(Apiaceae) using phylogenetic methods

Daniel Spalink

University of Wisconsin-

Madison

Advisor, Dr. Kenneth J. Sytsma, Phylogeny,

biogeography, ecology, and population genetics

of the North American bulrushes (Scirpus,

Cyperaceae): assessing the implications of

endemism in a changing climate

Simon Uribe-Convers

University of Idaho

Advisor, Dr. David C. Tank, Inferring Patterns

of Biodiversity in a young Andean ecosystem:

developing a novel high throughput sequencing

approach for phylogenetic and phylogeographic

studies in Bartsia (Orobanchaceae)

44

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Ecology Section Student

Travel Awards

Rupesh Kariyat

Pennsylvania State University

Advisor, Dr. Andrew Stephenson - Botany 2011

presentation: “Volatile mediated indirect defense

signaling is disrupted by inbreeding and genetic

variation in Horsenettle (Solanum carolinense L) .”

Co-author: Andrew Stephenson

Benjamin VanderWeide

Kansas State University

Advisor, Dr. David C. Hartnett - Botany 2011

presentation: “Mark-recapture analysis of

herbarium data from the northern Flint Hills of

Kansas, USA.” Co-authors: Brett Sandercock and

Carolyn Ferguson

Genetics Section Student

Research Awards

Genetics Section Student Research Awards provide

$500 for research funding and an additional $500

for attendance at a future BSA meeting.

Guadalupe Borja

Oklahoma State University

Masters Student Award - Advisor: Dr. Andrew

Doust, for the proposal titled “Integrating

phylogeny and population genetics: distinguishing

incomplete lineage sorting and gene flow to infer

the evolution of the Southeastern bladderpods

(Paysonia spp.).”

Kim Thompson

University of Cincinnati

Graduate Student Award - Advisor: Dr. David Lentz,

for the proposal titled “Chloroplast Microsatellite

Analysis of Manilkara zapota (Sapotaceae), a

Tropical Fruit and Timber Tree.”

Genetics Section Student

Travel Awards

Ari Novy

Rutgers University

Advisor, Dr. Jean Marie Hartman - Botany 2011

presentation: “Genetic Variation of Spartina

alterniflora Loisel. in the New York Metropolitan

Area and Its Relevance for Marsh Restoration.”

Co-authors, Peter E. Smouse, Jean Marie Hartman,

Lena Struwe, Joshua Honig, Chris Miller, and Stacy Bonos

Robert Baker

University of Colorado, Boulder

Advisor, Dr. Pamela Diggle

Botany 2011 presentation: “Making branches in

Mimulus: intraspecific developmental variation in

shoot architecture.” Co-author: Pamela Diggle

Geraldine Boyden

St. John’s University

Advisor, Dr. Dianella Howarth

Botany 2011 presentation: “CYCLOIDEA-like

genes are implicated in development and floral

patterning in Fedia cornucopiae (Valerianaceae).”

Co-authors: Diane Hardej, Amy Litt and Dianella

Howarth x

Michael Malahy

Oklahoma State University

Advisor, Dr. Andrew Doust

Botany 2011 presentation: “Pattern of vegetative

architectural development in green millet (Setaria

viridis) under varied planting densities.” Co-author:

Andrew Doust

Ana Maria Almeida

University of California, Berkeley

Advisor, Dr. Chelsea Specht - Botany 2011

presentation: “Gingers BCs: The role of MADS-

box genes in floral evolution in the Zingiberales.”

Co-authors: Wagner Otoni, Roxana Yocktenga and

Chelsea Specht

Irma Ortiz

University of California, Los Angeles

Advisor, Dr. Ann M. Hirsch

Botany 2011 presentation: “A Bacillus strain

isolated by undergraduate students at UCLA

promotes plant growth by procuring soil nutrients

and may also serve as a biological control agent.”

Co-authors: Allison Schwartz, Erin R. Sanders,

Andrew C. Diener and Ann M. Hirsch

Allison Schwartz

University of California, Los Angeles

Advisor, Dr. Ann M. Hirsch

Botany 2011 presentation: “A newly isolated

Bacillus strain affects legume plant architecture

and pea nodule morphology by secreting auxin.”

Co-authors: Irma Ortiz, Erin R. Sanders, Darleen

Demason and Ann M. Hirsch

45

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Angelle Bullard-Roberts

Florida International

University

Advisor, Dr. Bradley Bennett - Botany 2011

presentation: “Treating Sugar: Antidiabetic herbal

remedies in Trinidad and Tobago.” Co-author,

Bradley Bennett

Holly Summers

Cornell University

Advisor, Dr. Robert Raguso - Botany 2011

presentation: “Intraspecific variation in floral

display and breeding system in Oenothera flava

(Onagraceae).” Co-author, Robert Raguso

Lindsey Tuominenx

University of Georgia

Advisor, Dr. Chung-Jui Tsai - Botany 2011

presentation: “Perturbation of Populus

Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Suspension Cell

Cultures.” Co-authors, Raja S. Payyavula, Scott A.

Harding and Chung-Jui Tsai

Pteridological Section &

American Fern Society

Student Travel Awards

Fernando Matos

New York Botanical Garden

Advisor, Dr. Robbin Moran - Botany 2011

presentation: “The ferns and lycophytes of a

montane tropical forest in southern Bahia, Brazil.”

Co-authors, Paulo Henrique Labiak and Andre,

Amorim

Monique McHenry

University of Vermont

Advisor, Dr. David Barrington - Botany 2011

presentation: “Investigating morphological

diversity of Andean Polystichum (Dryopteridaceae):

seeking explanations for incongruence between

sequence variation and morphological variation.”

Co-author, Dr. David Barrington

Sean Ryan

San Diego State University

Advisor, Dr. Michael G. Simpson - Botany

2011 presentation: “Molecular Phylogenetic

Relationships and Character Evolution of Fritillaria

subgenus Liliorhiza.” Co-author, Michael G. Simpson

Mycological Section Student

Travel Awards

Carla Harper

University Of Kansas

Advisor, Dr. Thomas Taylor - Botany 2011

presentation: “Fungi from the Permian and Triassic

of Antarctica.” Co-authors, Thomas Taylor and

Michael Krings

Wittaya Kaonongbua

Indiana University

Advisor, Dr. James D. Bever - Botany 2011

presentation: “Xerospora xerophila gen. et sp. nov.,

a new arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus from a semi-

arid region of North America.” Co-author, James D. Bever

Phycological Section

Student Travel Award

Timothy Rocwell

Illinois State University

Advisor, Dr. Martha Cook - Botany 2011

presentation: “Cell division in the charophycean

green alga Entransia fimbriata.”

Phytochemical Section

Student Travel Award

Janna Rose

Florida International

University

Advisor, Dr. Bradley Bennett - Botany 2011

presentation: “Isolation of Ellagic acid from the

Bioassay-Guided Fractionation of Methanolic

Crude Extracts of Rosa canina L. Galls.”

46

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

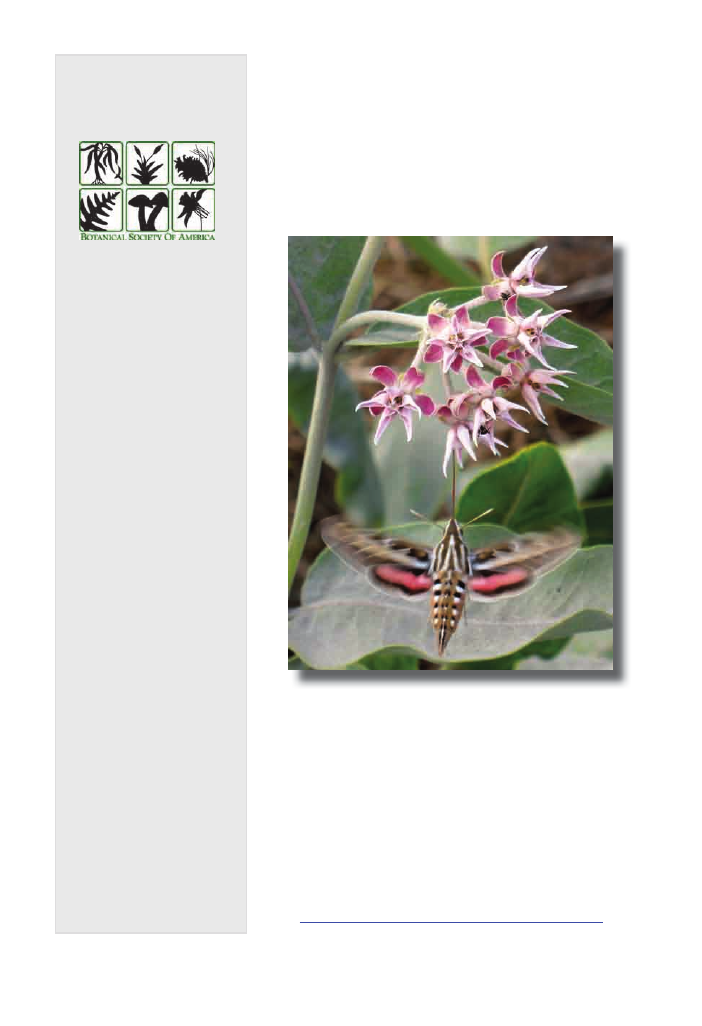

Triarch “Botanical Images” Student Travel Awards

This award provides acknowledgement and travel support to BSA meetings for outstanding student work

coupling digital images (botanical) with scientific explanations/descriptions designed for the general public.

(See front cover for this years 1st Place Winner!)

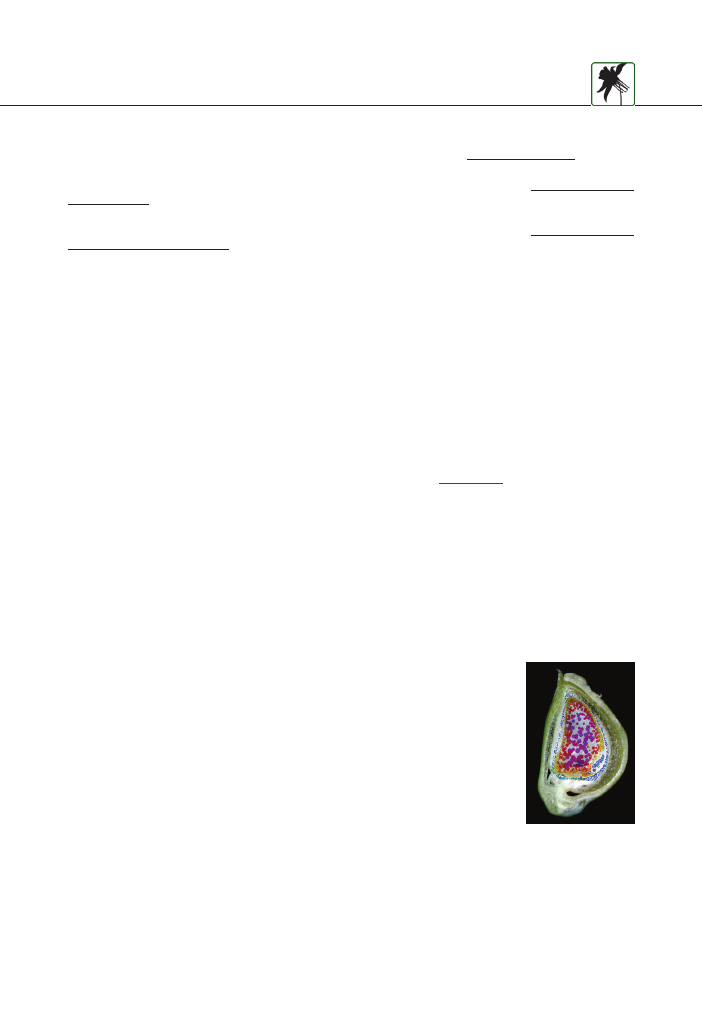

2nd Place - $250 Botany 2011 Student Travel Award

Allison Schwartz

University of California, Los Angeles

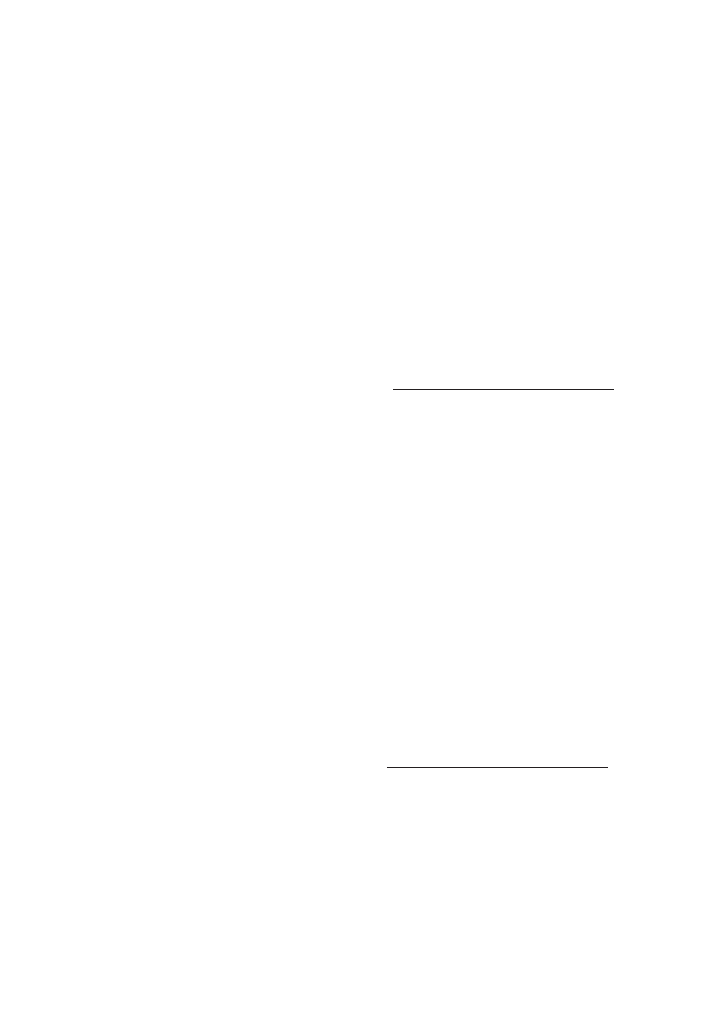

Top view of a root nodule from Pisum sativum with DR5::GUS auxin responsive reporter construct.

This image is a top view of a nodule on the root of a pea plant inoculated

with symbiotic rhizobia. In order to study how the development of root

nodules is influenced by Bacillus simplex 30N-5, a beneficial soil bacteria

capable of secreting the plant hormone auxin, we used a pea plant with a

reporter construct that is responsive to auxin. This DR5::GUS responsive

element drives the beta-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene, ultimately

resulting in a blue stain in areas responding to auxin. The “eyes” of this

happy nodule are actually the ends of two prongs that connect to a single

vein down the side of the nodule and end at the root’s xylem. These

blue vein-like structures later become the vascular tissue of the nodule,

allowing the nitrogen-fixing rhizobia inside access to water. Interestingly,

pea roots co-inoculated with both rhizobia and and B. simplex 30N-5

have larger nodules that develop more proto-vascular “veins” around the

sides of the nodule. This is likely due to the auxin that B. simplex can

secrete when associated with plant roots.

3rd Place (tie) $150 Botany 2011 Student Travel Award

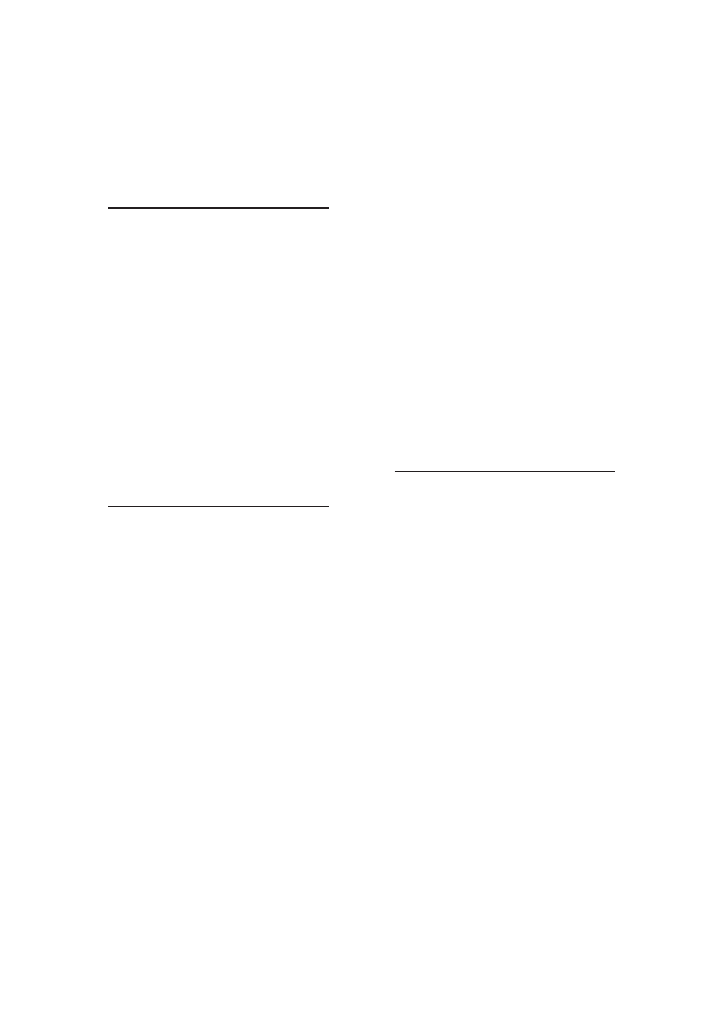

Alan Franck,

University of South Florida

One night only.

The nocturnal flowers of Harrisia regelii are quite large (ca. 17 cm long x

10 cm wide) compared to the elongate stem (ca. 1-2 cm wide) which can

be seen in the background on the right. From initial bud formation, the

flowers may take a month to effloresce. Despite this they last only one

night and begin to close and wilt the next day. Studying their flowers

can be difficult unless under constant supervision, as here in cultivation.

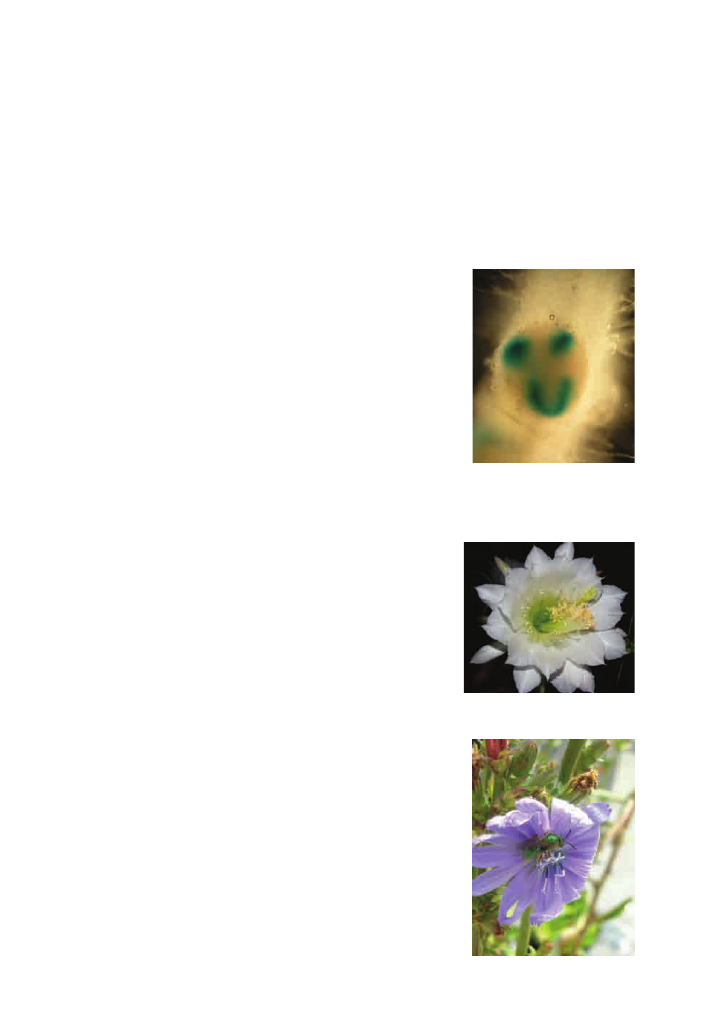

Tomas Zavada

University Of Massachusetts

Pollinating chicory

Cichorium intybus (chicory) is a self-incompatible species, owing its

genetic variety to the outcrossing nature. It means that pollen has to come

from other chicory plants in order to produce seeds. This process creates

genetic diversity in next generations. The closely related domesticated

species Cichorium endivia (endive) is self-compatible. Endive is a crop

only known from cultivation and has much lower genetic diversity

compared to chicory. Genetically uniform crop strains are in wide use

and one of the big challenges these days is to maintain the disappearing

diverse varieties of crops and their wild ancestors.

47

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

The BSA Young Botanist Awards

The purpose of these awards are to offer individual recognition to outstanding graduating seniors in the

plant sciences and to encourage their participation in the Botanical Society of America.

The 2011 “Certificate of Special Achievement” award recipients are:

• Gracie Benson-Martin, University Of California, Berkeley - Advisor, Dr. Chelsea D. Specht

• Amanda Bieber, Old Dominion University- Advisor, Dr. Lytton John Musselman

• Melanie Brusky, University of Cincinnati - Advisor, Dr. Theresa Culley

• Sasha Dow-Kitson, State University of New York at Plattsburgh - Advisor, Dr. Christopher T. Martine

• Joseph Gallagher, University of Florida- Advisor, Dr. Douglas Soltis

• Rachel Germain, University of Guelph - Advisor, Dr. Christina M. Caruso

• Arthur Grupe II, Humboldt State University - Advisor, Dr. Terry W. Henkel

• Guillaume Chomicki-Bayada, University of Manchester - Advisor, Dr. Simon Turner

• Alexandra Knight, Walsh University - Advisor, Dr. Jennifer A. Clevinger

• Matthew Lettre, University of Tennessee - Advisor, Dr. Joe Williams

• Starr Matsushita, University of Puget Sound - Advisor, Dr. John Hanson

• William McKnight Moore, University of California, Riverside - Advisor, Dr. Darleen DeMason

• Irma Ortiz, University of California, Los Angeles - Advisor, Dr. Ann M. Hirsch

• Jaime Patzer, Willamette University - Advisor, Dr. Susan Kephart

• Nikisha Patel University of Connecticut - Advisor, Dr. Kent E. Holsinger

• Kristin Pearson, Colorado College - Advisor, Dr. Tass Kelso

• Megan Philpott, University of Cincinnati - Advisor, Dr. Theresa Culley

• Melanie Poole, Connecticut College - Advisor, Dr. T. Page Owen Jr.

• Gerald Presley, Eastern Illinois University - Advisor, Dr. Andrew S. Methven

• Alex Scharf, State University of New York at Plattsburgh - Advisor, Dr. Christopher T. Martine

• Klara Scharnagl, Florida International University - Advisor, Dr. Suzanne Koptur

• Lilly Schelling, State University of New York at Plattsburgh - Advisor, Dr. Christopher T. Martine

• Emily Scherbatskoy, University of Colorado, Boulder - Advisor, Dr. Pamela K Diggle

• Paige Swanson, University of Colorado, Boulder - Advisor, Dr. Stephanie Mayer

• Ericka Veliz, Salisbury University - Advisor, Dr. Ryan Taylor

• Seana Walsh, University of Hawai’i at Manoa - Advisor, Dr. Tom A. Ranker

• Keir Wefferling, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee - Advisor, Dr. Sara Hoot

• Amanda Wildenberg, Eastern Illinois University - Advisor, Dr. Janice M. Coons

• Lindsey Worcester, Kansas State University - Advisor, Dr. Carolyn J. Ferguson

Congratulations to all of this

year’s winners!

48

American Journal of Botany

American Journal of Botany: PubMed, Web 2.0, and Reviewing

Editor Board

After many long months and with the strong support of BSA members and the Publications Committee, the

American Journal of Botany has been selected to be indexed and included in the Medline/PubMed database

(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). This is good news for authors and researchers: PubMed is one

of the leading sites used by researchers when conducting literature searches, and it is anticipated that BSA

members and authors will reap great benefits from the increased and varied exposure provided. Deposits

to PubMed will begin in June, and plans are in place to include previously published issues (back to late

1997, when AJB first officially went online). The AJB staff thanks everyone in the BSA who helped make

this possible, including all the authors, editors, and reviewers who contribute to the journal on a regular

basis, as well as those who submitted letters of support on our behalf as part of the application process.

Additionally, the AJB, with the help of the journal’s online host, HighWire Press, is now a Web 2.0 site.

Visitors to http://www.amjbot.org will immediately notice that the site is streamlined to be more user-

friendly and to offer more features than in the previous Web 1.0 site. The flexible three-column design

places many features at the visitor’s fingertips without taking attention away from the core article content.

Features most closely associated with the page content are placed closest to it, and this new platform allows

the editorial staff more direct control over the site. Feedback and suggestions are welcome. Please contact

the editorial staff at ajb@botany.org.

And finally, the editors and staff thank all of the applicants for the Reviewing Editor Board positions

for the AJB Primer Notes & Protocols online-only section. The response to the call for applicants was

fantastic. With the success and popularity of this section continuing to increase, these enthusiastic and

knowledgeable graduate students and post-docs will help to strengthen the quality and turnaround time of

papers and in return they will gain reviewing experience and mentorship from the section editors, as well

as acknowledgment in the journal.

President-elect

Elizabeth Kellogg

university of missouri - st. louis

Program Director

David Spooner

University of Wisconsin - Madison

Director at large-Development

Linda Graham

University of Wisconsin - Madison

Student Representative

Megan Ward

State University of New York - plattsburgh

BSA Election Results

Late Breaking News

Congratulations - Toby and all!

49

BSA Science Education

News & Notes

BSA Science Education News and Notes is a quarterly update about the BSA’s education efforts and the

broader education scene. We invite you to submit news items or ideas for future features. Contact: Claire

Hemingway, BSA Education Director, at chemingway@botany.org or Marshall Sundberg, PSB Editor, at psb@botany.org.

PlantingScience — BSA-led student research and science

mentoring program

PlantingScience Receives

Prestigious SPORE Award

What an honor! What a tribute to scientist mentors! What an amazing journey! PlantingScience was

honored to receive the AAAS Science Prize for Online Resources in Education (SPORE) Award. A key

reason cited by Science for selecting PlantingScience is its effectiveness at bringing the science process

to students in online collaboration with plant biologists. So this award belongs to the scientists and 14+

partner Societies.

Looking back to the Botany 2003 meetings when Dr. Bruce Alberts, then president of the National

Academies of Science, challenged the BSA to help enhance science experiences in classrooms, the journey

has been amazingly rewarding and timely. Education research documents the effectiveness of inquiry

learning and the short-shrift plants receive. Agencies place cyberlearning as a priority, both for policy and

funding initiatives. Teachers are clearly seeking out this kind of opportunity for their students to actively

and productively participate in authentic science experiences (see example of student team projects).

And, fortunately, botanists are unabashedly enamored with plants and eager to promote botanical literacy

within science literacy concerns. Moreover, societies with an interest in plants see benefits of collaborating

on outreach initiatives on education challenges of a national scope and scale.

It is thrilling to share this recognition with you. But it was a struggle to keep secret the good news we

received back in August 2010 until the article was published on March 25, 2011.

Read the Building Botanical Literacy essay: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/331/6024/1535.full

50

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Additional PlantingScience

Academic Year Highlights

Thank you! Much of the success of PlantingScience lies in your

volunteer efforts, which bring students and their teachers into the

science enterprise of doing science in collaboration with scientists.

PlantingScience grew again this year, and brought plants to 63 classes

across the country and even internationally. Over the Fall 2010 and

Spring 2011 sessions, students in 15 middle school, 45 high school, and 3

college classes conducted plant investigations with online mentors.

We are extremely grateful to the dedicated scientists from the Botanical

Society of America and our 14 Scientific Society partners who make

PlantingScience possible.

Thanks for this unique learning experience about plants also come

directly from the students to their mentors:

“… now i will take home the water [plant]and grow it to it’s maximum!

it was nice talking to you and i would be happy to let you know the results

of the water plant after further research! thank you for helping us and

challenging us to think” — Anderson School (middle school) student

“… Before this experiment I never really thought about plants and how

they grow. But this was very interesting to me in seeing how factors like

temperature effect germination and plant growth. Thanks for taking time

out of your day to help us.” — Kamehameha School (high school) student

“We just did our presentation to the class and I’d say it went pretty well!

… We all thank you so much for allowing us to explore the world of biology

and plants! We were so lucky to get such a friendly and consistent mentor!”

— C. Milton Wright High School student

“This project was a lot of fun and I learned a lot more than I thought I

would. It was very cool to see our plants go from mere seeds to flowers in

weeks. People like to think that humans are the most complex form of life,

but in my opinion all living things are extremely complex and wonderful.

Thank you for being our tutor. I’m grateful I cad the chance to do this, it

game me an interest I never thought I’d have.” — Nassau Community

College student

During this academic year, the Brassica Foundations of Genetics

module joined the Wonder of Seeds and Power of Sunlight as open to

any interested teacher to choose. Field-testing, led by Curriculum

Development Coordinator Teresa Woods, also continued this year on

four modules: pollination, Celery Challenge, C-Fern®, and Arabidopsis

genetics. An exciting international collaboration was part of the C-Fern®

field-testing this spring.

Become A Mentor - Get involved!

www.plantingscience.org

51

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

The project gave students “the chance to work

in real biological lab conditions and provided an

experience that has made them the envy of the

entire sixth grade!” says Stan Kosmoski, science

leader from the Ferrell Middle Magnet Center for

Language Exploration and Global Communication

in Tampa, Florida.

In February 2010, a Dutch web platform for

PlantingScience (http://www.nl.plantingscience.

org/) was launched by Edith Jonker from the

Bonhoeffercollege. Wanting to learn more about

PlantingScience, Jonker attended a two-week

institute for teachers in Texas sponsored by the

Botanical Society of America and Texas A&M

University last summer.

Kosmoski and Jonker met last summer at the

PlantingScience institute, and agreed to take the

fern inquiry a step further and introduce their

students online to each other. The thirty-two

students from The Netherlands had a chance to

practice their English, and those from Tampa,

Florida, learned a lot about a small country across

the Atlantic Ocean. Kosmoski notes that many of

the twenty-one students of Ferrell Middle Magnet

Center have never ventured beyond Tampa. “This

opportunity allows my students to not only meet

students from another country but also to find out

that they really aren’t all that different.”

Students Grow Ferns and

Friendship Across the Atlantic,

contributed by T. Woods

When spores from a special kind of fern were

carried to The Netherlands this winter for the first

time, more than plants grew. Sixth grade students

from The Netherlands and Tampa, Florida,

also developed friendships in an international

collaboration by sharing their experiences growing

ferns. Their work culminated in a videoconference

between the students held Thursday, April 7. (see

figure of Ferrell students viewing Dutch class and T.

Woods images projected on large screen.)

After corresponding online for a number of

weeks, the 12 to 13-year olds finally had the

chance to speak to each other live on camera.

They introduced themselves and shared about

their science inquiries. At first a little nervous

and very excited, students settled into asking each

other questions about growing ferns, robotics

competitions, daily living, and other interests.

Students were well prepared with the help of their

teachers: Sherri Cerni at Ferrell Middle Magnet in

Tampa; and Arjan de Graaf at Bonhoeffercollege in

Castricum, The Netherlands.

De Graaf reports, “PlantingScience feels like

education for the 21

st

century, with plants and

computers on the same table. The students enjoy

working in a community showing their results to

the world. There is much laughter in the classroom

– science, knowledge, fun and creativity. For the

first time I really regret having only two hours of

biology in a week!” (see image of Dutch students

asking Florida students a question via SKYPE.)

52

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

PlantingScience Summer Meetings

June 23-30, 2011. College Station, TX: Summer Institute for Teachers

This June is the last Summer Institute for Teachers under our current NSF award (DRL-0733280). And

what a wonderful capstone inquiry immersion experience is being planned by scientists Marsh Sundberg

and Larry Griffing along with teacher leaders Kim Parfitt and Randy Dix! Carol Stuessy and her graduate

students at Texas A&M University continue their fine job handling site coordination and education

research.

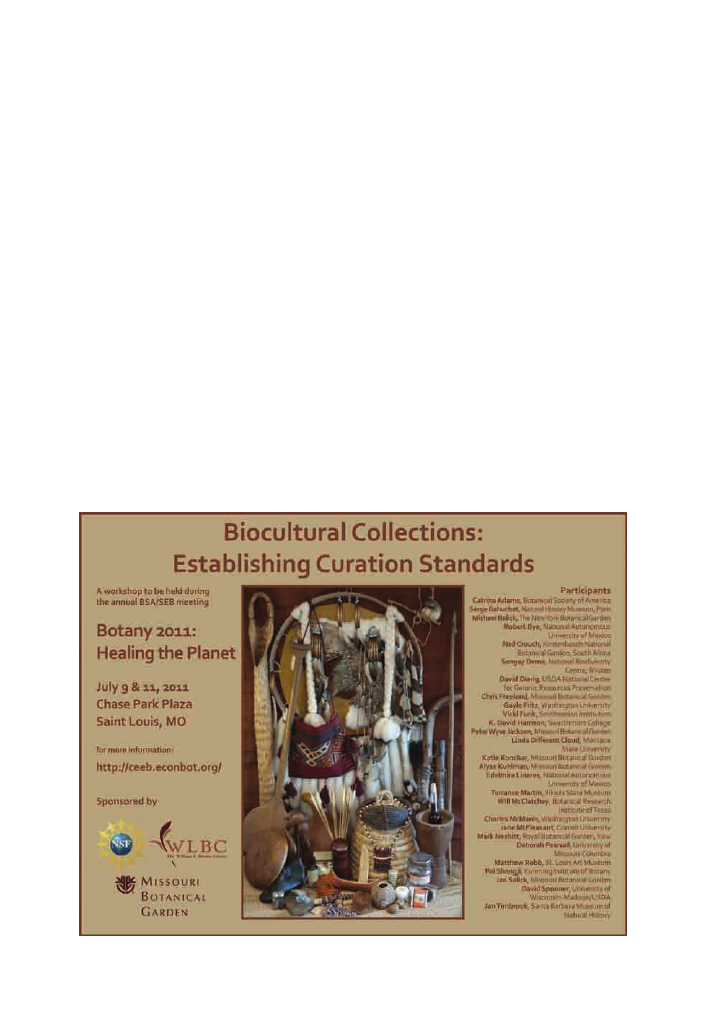

July 9-13, 2011. St. Louis, MO: Botany 2011

Attend the Teaching Section presentations at Botany 2011 to hear perspectives on PlantingScience from

a classroom teacher and education researchers. Kara Butterworth will share her students’ experiences

and showcase their projects. Co-PI Carol Stuessy and her graduate student Cheryl Ann Peterson present

analyses of online interactions on the PlantingScience website and classroom observations of teacher

implementations.

July 30, 2011. Melbourne, Australia: International Botanical Congress

Marsh Sundberg organized the “Rebuilding Botanical Capacity” Symposium at this summer’s IBC. Claire

Hemingway and Marsh Sundberg will share lessons learned thus far in PlantingScience by synthesizing

project findings and research components conducted by Texas A&M University and BSCS collaborators.

The plants have it!

The April/May 2011 issue of

Science Scope,

NSTA’s middle school journal,

is devoted to botany.

53

Teaching Principles of Experimen-

tal Design While Testing Optimal

Foraging Theory

Schwagmeyer, P.L. and S.A. Strickler 2011.

American Biology Teacher 73(4): 238-241.

For nectar-feeding insects, it is all about the food

reward to maximize net energy gain per unit time,

according to optimal foraging theory. The

authors present an outdoor laboratory exercise

manipulating nutritive value of flowers to

aid students’ understanding of designing and

interpreting experiments.

Engaging Students in Natural

Variation in the Introductory Biol-

ogy Laboratory via a Statistics-

based Inquiry Approach

Thompson, E.D., Bowling, B.V., Whitson, M.,

and R.F.C. Nazi. 2011. American Biology

Teacher 73(2): 100-104.

Variation is core to students’ understanding of

diversity, and the diversity leaf morphology lends

itself to student investigations. Seeking to make

introductory biology lab activities more than show-

and-tell, the authors describe a guided-inquiry that

draws on plants of the Ohio River Valley, but could

be adapted to other areas and to high school classes.

Doing an Ethnobotanical Survey in

the Life Sciences Classroom

De Beer, J., and B.-E. van Wyk. 2011. Ameri-

can Biology Teacher 73(3): 90-97.

The Power of Plants: Introducing

Ethnobotany and Biophilia into

Your Biology Class.

Babian, C. and P. Twig. 2011. American Biol-

ogy Teacher 73(4): 217-221.

Teaching Cultural and Botanical

Connections: Ethnobotany with Tea.

Poli, D. 2011. American Biology Teacher

73(4): 242.

Are looking for an interdisciplinary in-road for

botany in your courses? Consider ethnobotany.

The three articles above provide a variety of ideas

for diverse activities, to engage students with plants.

Moonstruck by Herbaria

Flannery, Maura C. American Biology Teacher

73(5):291-294.

As Maura notes, she is not a botanist, but she has

recently been drawn to botany (and attended last

year’s BSA meeting in Providence) and to herbaria in

particular. This “outsiders view” of herbaria is very

perceptive and a concise argument for the value of

herbaria to society, for science, and for education.

It provides some history and background as well as

some current trends and uses.

Editor’s Choice Reviews

The Kaplan Memorial Lecture Committee is proud to announce the Second Annual Kaplan

Memorial Lecture in Comparative Development at Botany 2011

This year’s speaker is Professor Ralph S. Quatrano who will speak on “Mechanisms of cellular

polarity: a comparative approach from mosses to seed plants.”

A ticketed cocktail repection will follow. Sign up at www.botanyconference.org

Second Annual

Kaplan Memorial Lecture in Comparative

Development in Botany 2011

Everyone is welcome!

54

Personalia

White House award for plant

research presented to

Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra

Jeffrey Ross-Ibarra has been selected to receive the

prestigious Presidential Early Career Award for

Scientists and Engineers. Ross-Ibarra, an assistant

professor in the Department of Plant Sciences at the

University of California - Davis, and BSA member,

was among 85 researchers chosen by President

Barack Obama to receive the award, the nation’s

highest honor for professionals in the early stages

of their scientific research careers. He will receive

the award at a later date during a White House

ceremony.

“I am quite humbled to be receiving such an honor

in only my second year at UC Davis, “ said Ross-

Ibarra.

He was nominated for the award by the U.S.

Department of Agriculture for a research project

that uses a novel approach, based on population

genetics, to identify genes that would be useful in

improving varieties of maize, also known as corn.

In this research project, Ross-Ibarra and his team

plan to identify the genotype, or genetic profile,

of 60,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms. These

are genetic variations that occur when just a single

nucleotide or building block in the DNA sequence

differs.

As part of its nomination, the U.S. Department of

Agriculture will provide Ross-Ibarra’s project with

$150,000 in annual support for three years.

Ross-Ibarra’s research program deals with the

evolutionary genetics of adaptation in plants, with a

particular focus on the study of plant domestication

and the evolution of crop plants. His laboratory

uses maize as a model crop for these studies.

“Much of this work uses population genetic

modeling to investigate the importance of natural

selection, gene flow and demographic history in

patterning diversity and divergence in the maize

genome,” he said.

In addition to work on identifying genes important

for maize domestication and improvement, Ross-

Ibarra’s lab is currently collaborating on a number

of projects, including work on chromosome

evolution and studies of natural populations of the

wild ancestor of maize in Mexico.

Ross-Ibarra’s nomination from the U.S. Department

of Agriculture noted that the plant geneticist has

“an excellent track record of productivity ... and

professional service.” It added that, by focusing

on maize, one of the most important crops for the

U.S. economy, and on techniques that can be used

with other important cereal crops, Ross-Ibarra’s

research will help “promote sustainability of U.S.

agriculture and international food security, while

enhancing the environment by reducing pressure

on cultivatable land resources.”

Ross-Ibarra and colleagues also are working to

facilitate international scientific exchange through

a program that will bring students from Mexico

to work in U.S. laboratories, where they will study

chromosome biology in maize. The exchange

program is part of a research project, funded by

the National Science Foundation, that focuses on

completing the sequence and assembly of maize

centromeres, the central region of chromosomes.

After earning his doctoral degree in genetics from

the University of Georgia in 2006, Ross-Ibarra

completed his postdoctoral research at UC Irvine.

He also received a master’s degree in botany in 2000

and a bachelor’s degree in botany in 1998, both

from UC Riverside. He joined the UC Davis faculty

in 2009

55

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Jonathan Wendel

Wendel’s research interests

encompass molecular & genome

evolution, phylogenetics, and

phenotypic evolution of higher

plants. He uses a diverse set of

technologies and approaches

to explore the manner in

which genomes change over

evolutionary time, as well as

the relationship between these

events and morphological

change. His particular interest is

in the mysterious and common

phenomenon of polyploidy, with

a special focus on the cotton

genus

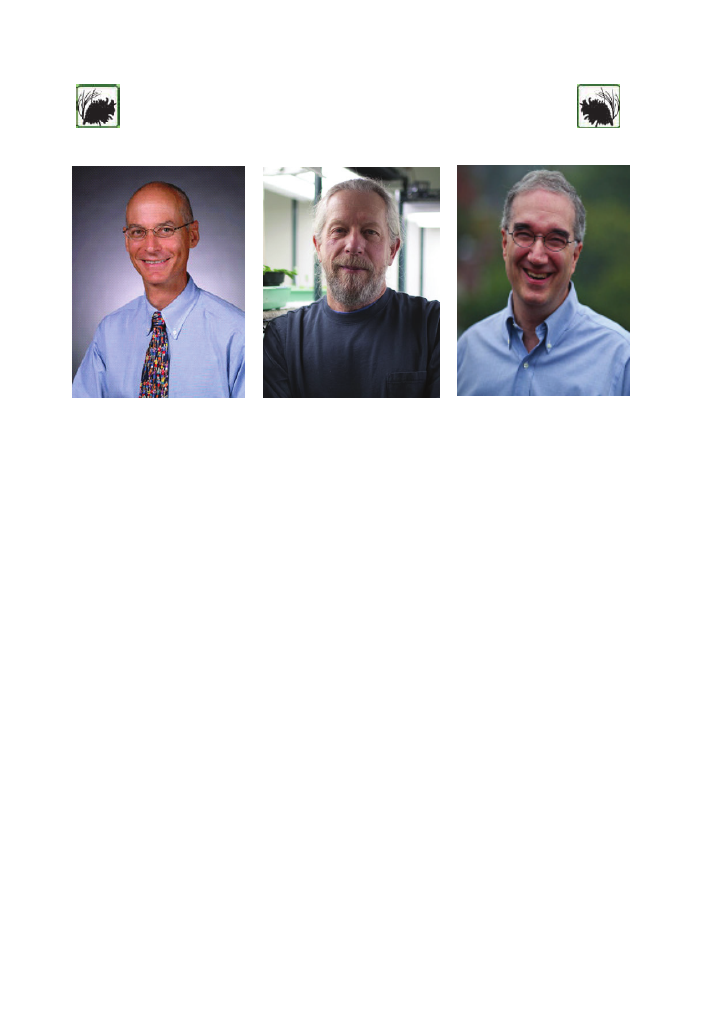

2011 AAAS Fellows

Roger Hangarter

Hangarter is interested in the

physiological and molecular

mechanisms by which plants

perceive and respond to

environmental stimuli. Together,

light and gravity have profound

effects on plant development and

much of his research focuses on how

plants integrate the information

from these environmental stimuli

in order to understand how

various environmental sensory

responses function and interact to

coordinately regulate plant growth

and development. Hangarter is

also the lead creator of sLowlife, a

dynamic multi-media exhibition

that features time-lapse movies

to show plants as living beings,

sensing and responding to their

environment.

William (Ned)

Friedman

Friedman’s research is devoted

to investigating the origin and

early evolution of flowering plants

(Darwin’s abominable mystery).

His primary focus is on the

evolution of double fertilization

and endosperm, two of the most

important and defining features

of flowering plants. He also has

a strong interest in the first major

radiation of photosynthetic life

on land, that of the vascular

plants.

Congratulations, Gentlemen!

56

Coming up Short:

Only 39 percent of North

American endangered plant

species are protected in

collections

The first comprehensive baseline knowledge on

North America’s plant conservation efforts just

published

Washington, D.C. – Only 39 percent of the nearly

10,000 North American plant species threatened

with extinction are protected by being maintained

in collections, according to the first comprehensive

listing of the threatened plant species in Canada,

Mexico and the United States. Seed banks or living

collections maintained by public gardens and

conservation organizations across North America

provide an insurance policy against extinction for

many threatened species.

The North American Collections Assessment

– conducted collaboratively by Botanic Gardens

Conservation International U.S., the U.S.

Botanic Garden, and Harvard University’s

Arnold Arboretum – found that 3,681 of 9,494

of North America’s most threatened plant species

are maintained in 230 collections. Much more

collaborative work is needed to conserve North

America’s botanical wealth and to provide true

protection against extinction, say the report’s

authors.

Andrea Kramer, Botanic Gardens Conservation

International U.S. executive director, said, “These

assessment results are hopeful, but also a call

to action. For many public gardens, this report

marks the first time their potential to assist in the

conservation effort has been recognized. We hope

this is a watershed moment.”

“As the U.S. Botanic Garden, we felt a critical need

for a common baseline of understanding among

the entire conservation community,” said Holly

Shimizu, U.S. Botanic Garden executive director.

“To move forward together to protect North

America’s native plants, we have to understand

where we are today. Now that we know both what

is threatened and what needs to be protected, there

is a solid foundation on which to build future

conservation work.”

“One of the lessons we learned from this

assessment is how important it is to curate for

conservation,” said Michael Dosmann, curator

of living collections at the Arnold Arboretum.

“Curators and horticulturists have not always

considered conservation value as they go about their

routines. Yet by participating in this assessment,

many for the very first time saw the direct value

of their plants in bolstering efforts to conserve

our threatened flora. We hope this becomes a new

paradigm in collections management.”

Assessment results indicate that North America

did not reach the Global Strategy for Plant

Conservation’s (GSPC) Target 8 goal set in 2002 of

protecting 60 percent of threatened plant species in

collections by 2010. While botanical organizations

across Canada, Mexico and the United States

are making progress to achieve these targets,

the report found that 3,500 or more additional

threatened plant species will need to be added to

current collections to meet the new GSPC goal of

conserving 75 percent of known threatened species

in North America by 2020. This will require nearly

doubling the current capacity.

The assessment calls for the strengthening

of conservation networks and collaboration

in conservation planning and data sharing.

Institutions are urged to contribute plant lists to

BGCI’s PlantSearch database and update them

regularly. It is crucial to increase cooperation and

coordination among a broad and diverse network

of gardens and conservation organizations with

different expertise and resources. To win this race

against extinction, conservation organizations will

need to prioritize the development of genetically

diverse and secure collections to ensure meaningful

protection of threatened plants.

Additional information and the full North

American Collections Assessment can be found at

www.bgci.org/usa/MakeYourCollectionsCount.

ANNOUNCEMENTS

57

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

The Catalina Island Conservancy Herbarium (CATA) – call for

institutional exchanges

Catalina Island is one of the eight California Channel Islands, located approximately 35 km southwest

of Los Angeles. At 194 km2, 88% of which is managed by the non-profit land trust Catalina Island

Conservancy, Catalina is the third largest Channel Island and is the second tallest with an elevation of 639

meters. Mediterranean in climate, at least 8 defined plant communities (and up to 16) have been identified

on the island, from coastal marsh, to island woodlands, to open grasslands. Over 400 species of plants are

native to the island and nearly 200 non-native plants have become naturalized or are invasive on the island.

The staff of the Catalina Island Conservancy Herbarium (CATA) is responsible for cataloging the plant

diversity of Catalina Island as part of a long term, integrated plant management and conservation program.

In addition to documenting the unique and varied plants of the island, CATA staff is interested in building

the herbarium as a research and education tool. Herbaria specializing in plants of the California Floristic

Province as well as herbaria with Mediterranean climate floras are encouraged to enter into reciprocal

exchanges with CATA. For more information about CATA please see our listing at Index Herbariorum,

http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/herbarium.php?irn=158628. For additional information on the Conservancy

and Catalina Island or to establish an exchange, please contact the curator, John R. Clark, Ph.D., at

herbarium@catalinaconservancy.org, 310.510.9544, PO Box 2739, Avalon, CA 90704, USA.

Dr. Catrina Adams

Education Technology Coordinator

Catrina joined the BSA in March 2011 after working as an instructor for

the Missouri Botanical Gardens, where she helped to run a field science

training program for St. Louis area high school students and taught classes

on the ethnobotany of native Missouri plants. In 2009, Catrina received

her Ph.D. from Washington University with a focus in paleoethnobotany.

For her dissertation she studied seed remains from a Viking Age/Medieval

farm site in Scotland’s Orkney Islands to learn more about agricultural and

land use changes over time. She has a strong interest in inquiry learning,

teaching technologies, and helping students to experience authentic

scientific research. Her focus at the BSA is to continue to grow and improve

the PlantingScience program and to enhance interactions among the

program’s scientists, teachers, and students.

Birgit Spears

Development Director

Birgit brings a broad set of skills to the BSA with her combined experience

in development and marketing communications. Prior to joining the

BSA, Birgit helped design and launch a comprehensive brand and capital

campaign plan for a non-profit broadcast and media arts organization in St.

Louis. Earlier in her career, she launched a non-profit visual and performing

arts organization in New York City that served artists from around the

world. In addition to her non-profit experience, she has also worked in

the private sector with marketing agencies and international technology

companies where she was responsible for communications strategies and

business development. Birgit’s focus at BSA will be to assist with developing

relationships to increase awareness and funding opportunities through corporate and foundation giving,

and to further develop strategic partnerships, and committee memberships that will help achieve the long-

term goals of the BSA.

Welcome New BSA Staff Members

58

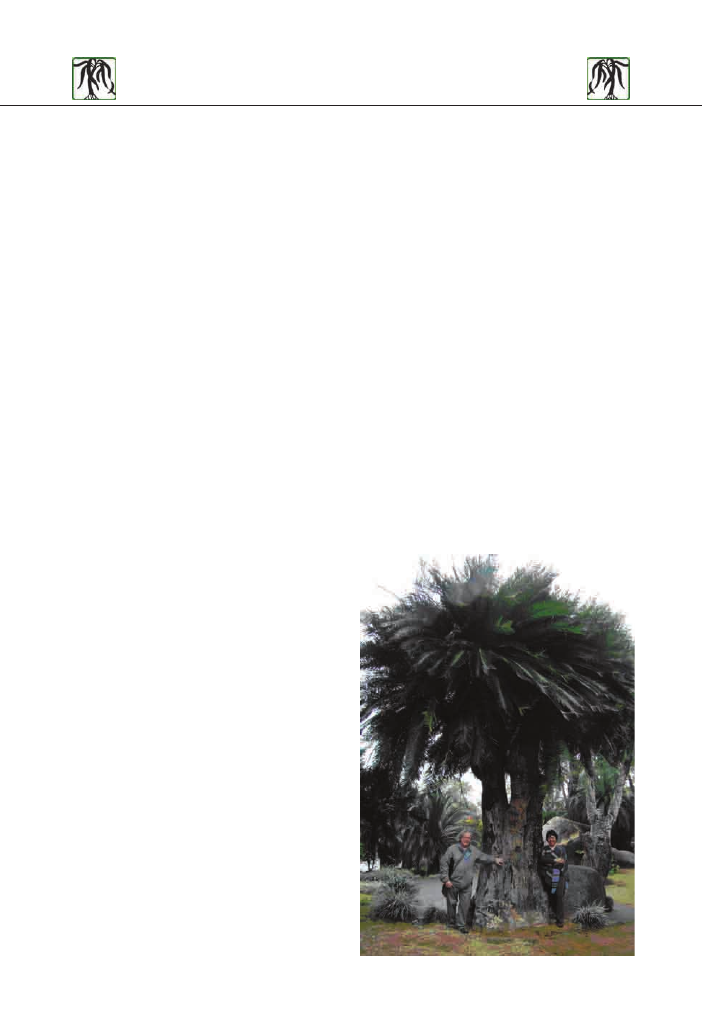

Cycad 2011 Meeting in

Shenzhen, China.

The 9th International Conference on Cycad

Biology is being hosted by Fairylake Botanic

Garden in Shenzhen, China, on December 1-7,

2011. Held every three years, this cycad meeting

brings together scientists, professionals, and

dedicated enthusiasts to share their work, catch up

with each other and learn the latest findings from

the field, garden and laboratory. Under the auspices

of the IUCN, the Cycad Specialist Group also holds

their regular meeting at this conference. Cycad 2011

is truly a “rare event,” with so many world cycad

experts and enthusiasts together in such a unique

place. We write to enthusiastically encourage you to

be a part of Cycad 2011. No other meeting this year

will focus on this beloved group of plants, with such

depth, breadth, expertise and interest.

The Conference Program

The Cycad 2011 Organizing Committee is

building the conference around eight themes:

(1) Genetics and Genomics, (2) Conservation,

(3) Taxonomy and Phylogeny, (4) Ecology, (5)

Horticulture, (6) Toxicology, (7) Economic Botany,

and (8) Information Management. In addition to

presentations, Cycad 2011 will include networking

opportunities, cultural events, a tour of Fairylake

Botanical Garden and the Chinese National Cycad

Conservation Center, and a field visit to a native

Cycas fairylakea population. A Post-Conference

Field Tour will also feature visits to native

populations of Cycas debaoensis, C. dolichophylla,

C. ferruginea, C. sexseminifera, C. segmentifida and

other species.

Fairylake Botanical Garden

Fairylake Botanical Garden is a world-class

horticultural treasure which sees millions of

visitors per year, in a unique tropical landsite

covering 590 hectares (1,457 acres). As part of the

Chinese Academy of Science, a very active and

robust research program at Fairylake focuses on

plant biology and horticulture, and this augments

the garden’s conservation efforts. The Chinese

National Cycad Conservation Center is located at

Fairylake Botanical Garden, and includes extensive

conservation plantings in a beautiful valley

setting, as well as a collection of spectacular dwarf

cycads on display in a unique courtyard as well

as an extensive horticulture program. The cycad

collection at Fairylake is unique in breadth, depth

and beauty. Extensive conservation horticulture

of Cycas debaoensis is a leading project, among

many other rare Cycas species being propagated

at Fairylake. Fairylake Botanical Garden also hosts

the Shenzhen Paleontological Museum, home to

many spectacular fossils centered on an enormous

20 meter Sauropod, Mamenchisaurus jingyanebsis.

The museum’s outdoor exhibition features one of

the world’s finest collections of fossilized wood

from China and around the world, beautifully

arranged as living forest, and landscaped with tree

ferns, cycads, podocarps and other architectural

plantings.

Shenzhen

Shenzhen is a young, vibrant city that has been

recognized for its foresight in city planning and its

leadership in civic horticulture. Extensive space is

devoted to public parks, well-designed roadside

landscapes, vibrant floral displays and impressive

groves of palms and flowering trees. Shenzhen is

a leader in innovating “Green Roofs,” and rooftop

gardens are increasingly common. Shenzhen has

recently been recognized as a “Garden City” and a

“Green City” for these accomplishments.

Meetings

59

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Travel to Cycad 2011

Travel to Shenzhen is quite easy. Shenzhen city is situated adjacent to Hong Kong in south China. A ferry

terminal located within Hong Kong International Airport (HKIA) offers regular service without clearing

Hong Kong customs. Ferry service from HKIA to the Shekou port takes just under one hour, and runs

more or less hourly between 9:00 and 21:20. Visitors can check luggage directly to Shekou Port. Visitors

will require a Chinese visa, which is easily obtained through a number of service providers. Fairylake

Botanical Garden is arranging transport for conference delegates from the Shekou port to the Conference

hotel. In addition, express or MTR (Mass Transit Railway) is also available from HKIA to Shenzhen Luohu

Station or Huanggang Customs, or directly to some hotels.

For more information

Please see the conference website at www.cycad2011.com for more information, including dates,

registration info, and important conference announcements.

We look forward to seeing you

Please make your plans right away -- We look forward to seeing you at Cycad 2011!

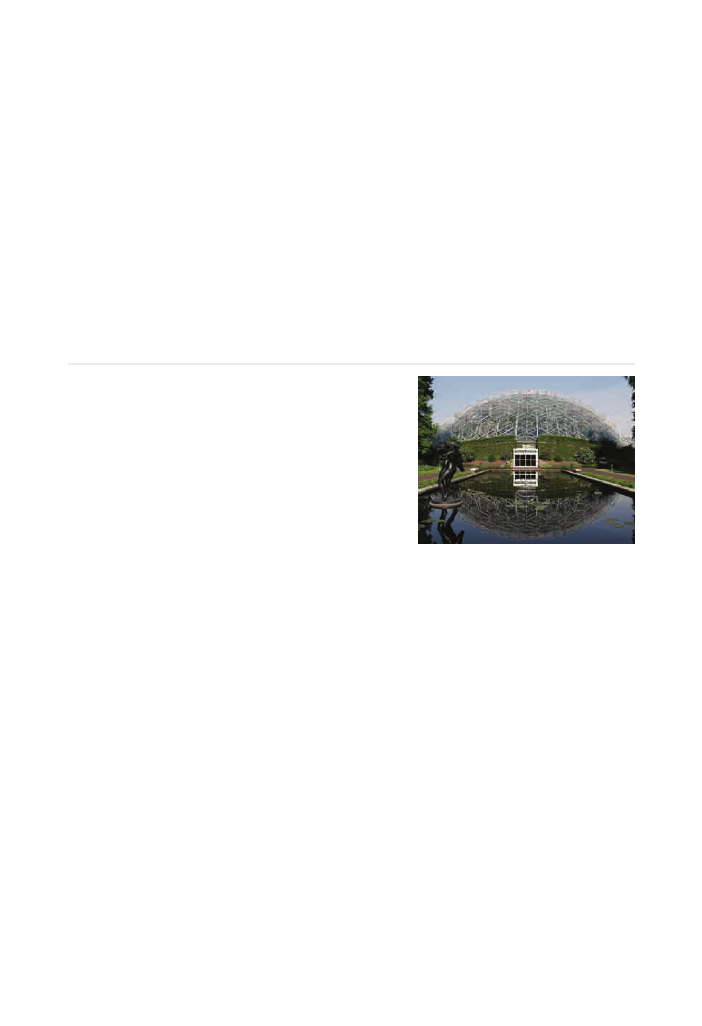

GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR PLANT

CONSERVATION CONFERENCE

TO TAKE PLACE AT THE

MISSOURI BOTANICAL GARDEN

Conference to Address

Worldwide Goal to Advance

Plant Conservation

The Missouri Botanical Garden will host the

2011 Conference of the Global Strategy for Plant

Conservation, bringing together plant conservation

scientists, policy makers and practitioners from

all over the world to share methods and results

that will advance plant conservation measurably.

This conference, titled “Supporting the worldwide

implementation of the Global Strategy for

Plant Conservation,” is organized by the Global

Partnership for Plant Conservation (GPPC) in

association with the Secretariat of the Convention

on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Botanic

Gardens Conservation International (BGCI). The

conference is expected to attract a wide range of

participants to share their experiences and further

the development of plant conservation action in

this the U.N. Decade of Biological Diversity.

“The adoption of the updated Global Strategy

for Plant Conservation in 2010 provided a new

challenge for the world to halt the loss of plants

by the year 2020,” said Missouri Botanical Garden

President Peter Wyse Jackson. “If we are to be

successful in this work, we need to be clear about

our individual priorities and responsibilities.”

In October 2010 in Nagoya, Japan, the 10th

Conference of the Parties of the Convention

on Biological Diversity adopted a decision

incorporating a consolidated update of the Global

Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC) from

2011 through 2020, including 16 targets for plant

conservation to be achieved by 2020. The role of

the Global Partnership for Plant Conservation is

recognized by by the CBD in supporting GSPC

implementation worldwide; the conference at the

Garden aims to help guide future plant conservation

priorities.

The conference will assist in efforts made to expand

and evaluate progress in implementing the GSPC

from 2002 to 2010 and how these experiences can

support enhanced implementation over the coming

decade. Examples will be shared from around the

world on GSPC implementation, particularly

during the period 2002 to 2010, to provide

guidance and support for national and regional

GSPC implementation entering into the new phase.

Sharing experiences will assist those that are setting

national targets for plant conservation or using the

GSPC and CBD Strategic Plan to provide a flexible

60

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Notice for a Recently Published

Ethnobotanical Study

That Hard Hot Land: Botanical

Collecting Expedition in the Anglo-

Egyptian Sudan, 1933-1934.

Mary L. Keenan.

2011. ISBN: 978-0-9564910-0-8 (Cloth

£52plus post & package)

416 pages, 22 maps, 270 photographs.

Published by the author.

Between December 1933 and April 1934 three

very different men travelled 6000 miles through

western and southern Sudan by train, motor car,

lorry, river steamer, donkey, and on foot. The

expedition aimed to investigate the relationship

between the vegetation and soil through a strip of

country with similar temperatures but with great

variations in rainfall.

James Edgar Dandy, botanist at the British

Museum, Natural History Department (later

Head Keeper of Botany), wrote a diary, took over

300 photographs and collected over 700 plants.

Dunstan Skilbeck, lecturer in Soil Science at

Oxford University (later Principal of Wye College,

London), collected numerous soil samples and

wrote a diary. Cecil Graham Traquair Morison,

lecturer in Soil Science at Oxford University, was

leader of the expedition (continued to lecture at

Oxford, and undertook further ecological surveys

in Africa, including the Sudan).

Accompanying them were six local men, employed

as cook, drivers, and servants. Dandy?s diary

and field notebook, short and to the point, are

supplemented by his photographs and letters, and

complement Skilbeck?s longer, more colourful

and descriptive diary. The diaries record the

work undertaken, the terrain, people met, daily

hardships, humour, aggravations, conversations,

soul searching, and life changing events.

A ten day trek to the volcanic caldera of Jebel

Marra, Darfur is described with geological,

botanical, and ethnographical observations.

Journeys are described, hunting with local tribes,

fishing, and shooting for bushmeat. Tribes

and their customs, chiefs, government officials,

governors, district commissioners, doctors,

teachers, tourists, missionaries, and all others

met during the expedition; as well as agriculture,

water, cotton growing, salt mining, experimental

fruit farms, roads and railways, hospitals, schools,

and much more, are described and researched.

framework for their efforts in plant conservation at

all levels.

Attendees will support the ongoing efforts to

consider and develop further the technical

rationales, milestones and indicators for the GSPC

up to 2020 and synchronize with the Strategic Plan

for Biodiversity 2011-2020. In addition, attendees

will help evaluate a draft GSPC toolkit that is being

prepared to support GSPC implementation at all

levels prior to its submission for review by the

Convention.

The conference will also provide an opportunity

for strategic discussion on mainstreaming plant

conservation in national development agendas,

such as including links to the implementation of the

CBD’s Strategic Plan as well as providing guidance

and suggestions for countries that are updating

National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans

(NBSAPs) to include the targets of the GSPC.

Finally, the conference aims to build leadership

amongst the participating organizations for

monitoring and delivery of the GSPC targets going

forward.

“I have no doubt that this conference will help

to set a working agenda for many participating

organizations worldwide,” said Wyse Jackson.

With scientists working on six continents in 35

countries around the globe, the Missouri Botanical

Garden has one of the three largest plant science

programs in the world, along with The New York

Botanical Garden and the Royal Botanic Gardens,

Kew (outside London). The Garden focuses its

work on areas that are rich in biodiversity yet

threatened by habitat destruction, and operates

the world’s most active research and training

programs in tropical botany. Garden scientists

collaborate with local institutions, schools and

indigenous peoples to understand plants, create

awareness, offer alternatives and craft conservation

strategies. The Garden is striving for a world that

can sustain us without sacrificing prosperity for

future generation, a world where people share a

commitment to manage biological diversity for the

common benefit.

For more information on the Global Strategy for

Plant Conservation Conference, visit: www.mobot.

org/gppc2011

For more information about the Missouri Botanical

Garden visit: www.mobot.org. The Missouri

Botanical Garden is located at 4344 Shaw Blvd., St.

Louis, Missouri, 63110

61

Central Concepts:

Humans use an impressive number of species, but

we also rely heavily on only a small number of

species/families for much of our caloric intake.

The importance of certain taxonomic groups above

others is perhaps less about chance than it is related

to the combination of evolutionary history within

lineages and thousands of years of agricultural and

horticultural activities (including the selection of

desirable characteristics within crops) by humans.

Communities of organisms (the market plant

“community” used as a proxy) can be quantified

in terms of the taxa of which they consist. These

calculations can be useful in drawing comparisons

within and between communities, and can generate

new hypotheses.

Materials:

• Recording materials (notebooks/writing

boards, pencils/pens)

• Taxonomic resources (books and computer access)

• Excel or other spreadsheet software

• Transportation to site (we use institutional vans)

Introduction

The Market Botany lab module has been run with

up to 20 students at a time. The activity can be used

as a field trip in any botany course above the 100

level or modified and used as a lab-based activity

(and then perhaps serve a larger class size). As

presented here, the module consists of three parts,

the first two completed during a 3-hour lab period

and the third done for homework.

An underlying pedagogical concept here is one

I try to employ in all of my botany coursework:

Students are more likely to remember subject

matter if they have a personal connection with the

material. The value of this approach was impressed

on me as an undergraduate student by Dr. Roger

Locandro, Rutgers University, who never missed

an opportunity to feed to us the very things we

were learning about. Although students are not

eating from the shelves during this module, per

se, this activity does connect taxonomic/biological

concepts and names with their personal experiences

of familiar foods and products.

Market Botany: A plant biodiversity

lab module

Christopher T. Martine

Dept. Biological Sciences, SUNY Plattsburgh

101 Broad Street, Plattsburgh, NY 12901

christopher.martine@plattsburgh.edu

Submitted 24 January, 2011

Accepted 26 April, 2011

Abstract

Market Botany is a variation on an approach many

instructors of plant diversity have employed: using

the grocery store as a teaching space (see Appendix

A). This version, included as a module in my Field

Botany (BIO 345) course at the State University

of New York at Plattsburgh since 2007, meets

experiential curriculum objectives by employing

a group research experience during which the

grocery store is used as “the field” for a biodiversity

survey. Students are introduced to general concepts

in community ecology, in concert with learning

objectives related to plant diversity and economic

botany.

Objectives:

• Students recognize the diversity of plant

species/groups we use as foods and in other

products through an experiential learning

process.

• Students evaluate the importance of certain

plants over others in terms of human usage.

• Students become familiar with the taxonomic

hierarchy of the Plant Kingdom, including key

families and orders.

• Students learn to compute and compare

measures of species richness and relative

abundance.

• Students access and utilize current hard

copy and electronic resources for taxonomic

information.

Reports and Reviews

62

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Once the students record a species they should

not do so again. While many plant names will be

obvious, others might be more difficult to recognize.

I tell them it is better to record something they

think could be a plant name then to leave it out;

quality control can wait until the master list is

compiled back in the lab. Although they are sent

blindly into the data collection, there is a benefit to

this approach (see later). My role during the survey

is to move throughout the store, checking on each

group/student and occasionally offering assistance

or making sure that they have recorded rare-

occurrence species that might otherwise be missed

(e.g., “Did you get this guarana soda over here?”).

The students are highly unlikely to catch every

species, given the short timeframe and their varying

levels of knowledge. My goal in the activity is not to

make an exhaustive list, but to gather enough data

points such that the results can be accepted with

confidence.

I prefer to let the students record their data in the

fashion they find most agreeable, but a standardized

datasheet could just as easily be generated and

provided. The keys are to gather the data quickly,

prevent your participants from feeling frustrated

or overwhelmed, and encourage them to become

invested in the quality and comprehensiveness of

their datasets.

The class is typically divided among the following

aisles of the store (and these then become categories

of use to be evaluated later):

1. Deli/bakery

2. Produce

3. Pharmacy and health

4. Beauty/cleaning

5. Pet and baby

6. Chips/soda/seasonal

7. Candy/nuts/crackers

8. Pasta/canned vegetables/condiments

9. Tea/ethnic/soups

10. Baking, spices + Dairy/beer (2 aisles)

11. Cereal/juices/canned fruits

12. Bread/jellies/frozen desserts

13. Frozen vegetables/entrees

Not assigned: Floral (plenty of interesting things,

but too many species without identification labels).

Permission from the store should be sought for the

market survey. I contact the manager of our local

grocery store a few weeks before our scheduled

visits so that he can clear the activity with the

chain’s corporate office. I have never been denied

permission, in part because we do not violate the

three main requests of the store manager: 1) No

photos are taken in the store, 2) The activity should

not interfere with customer access to products

(time of day can be an important factor), and 3)

When we leave, shelves and displays look the same

as they did when we arrived. The latter request is

easily met by reminding students to put products

back exactly as they were found, including facing

the fronts of packages/cans out.

Activity:

Part One (Store survey)

60-80 minutes (not including

travel time):

Summary: Students explore the diversity of plant-

based products available for sale at a local grocery

store by recording the names of plant products

they encounter. How botanically diverse are the

products we use everyday?

Methods:

After a brief introduction to the activity and the

goals of the visit, students/teams are given pre-

assigned sections of the store (usually by aisle). This

is easiest to do if you are already familiar with the

store you visit for class, something that is possible

through one pre-class visit. Deciding who to

assign where and who will work individually is an

important step and should be done based on your

knowledge of each student’s ability and personal

interests – and with some attention to who works

well with who.

Students are told to keep a cumulative list of the

species they encounter in their assigned aisle

by reading labels and ingredient lists. Given the

content of my course, the students already know

something about the use of common versus

Latin names – including how to properly format

the latter. Because of this they quickly recognize

the inconsistencies in the way plant names are

included in product ingredient lists (the bane of

nomenclaturally-inclined botanists everywhere!).

63

Plant Science Bulletin 57(2) 2011

Part Two

(Taxonomic research and data

entry), 45-80 minutes:

Summary: Students research the taxonomy of the

plants they recorded during the survey and enter

that information into a common spreadsheet. Do

our data support the observations/assumptions we

made while recording?

M

ethods:

In the classroom/lab, the list of species is now

actively entered into a common spreadsheet

managed by the instructor and projected onto a

screen so the class can follow along. The spreadsheet

has the following headings: species name, family,

order, upper taxonomic group (see below), and one

heading per category of use (in this case, each use

category is an aisle of the store).

Tasks:

Record the occurrence of each species (and the

sections in which each was recorded) on the

common spreadsheet, using one row per species

and one column per survey team (so one column

per store aisle). An individual species may thus

be recorded (by entering a “1”) in more than one

survey column, thus providing us with both a list

of species and a record of the total occurrences of

each species. Using a “1” for each occurrence allows

the students to easily sum up columns later (just by

clicking the column). As each student/team reports

this information to the instructor, the class starts

searching for and recording:

• Latin name for each species.

• Family each species belongs to.

• Order each family belongs to. (It is worth noting

here that Family and Order definitions may vary

depending on the resources the students use. My

tendency is to lean towards the designations used

in the latest edition of the textbook I use in our

plant systematic course (currently Judd, et al.) in

order to maintain consistency.

• “Upper Taxonomy” of each Order (Algae,

Bryophytes, Fern Allies, Ferns, Gymnosperms,

Monocot Angiosperms, Non-monocot

Angiosperms. (It is a given that “algae,” “fern

allies,” “ferns,” and “dicots” are all problematic

names. “Non-monocot angiosperms” can be

used in place of the now-obsolete term, “dicots,”

but the others are still used here – and addressed

by me in this and other courses as appropriate.)

Some sections are more challenging than others,

whether by the volume of products or diversity of

ingredients they contain (e.g., pharmacy, ethnic).

The produce section has many species, but they

are all obvious and easy to record. Other sections

might be more difficult, so I find it best to try

to match those assignments to students with a

strong botanical background or specific interests.

Pharmacy/health is both rich in plant products

and inclusive of “oddball” species that may not

be recognizable to all students; this is a good

assignment for the student(s) with an interest in