PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

A Publication of the Botanical Society of America, Inc.

VOLUME 41, NUMBER 3, FALL 1995

The Botanical Society of America: The Society for ALL Plant Biologists

Table of Contents

News from the Society, the Sections and the Committees

BSA Concludes Annual Meeting in San Diego 38

Botany for the Next Millennium: A Note from the President 38

Young Botanist Awards - 1995 39

New Corresponding Members of the Society Elected 40

Botanical Society of America 1995 Dinner for All Botanists 40

Reports from the Committees 41

Reports from the Sections 42

Thanks for Helping! 44

Awards and Prizes at BSA Annual Meeting 45

Commentary

Usenet Newsgroups for Botany and Systematics 46

Announcements

Forum on Mentoring Graduate Students 47

Science and Biodiversity Policy Now Available from AIBS 47

Request for Botanical Literature 47

Back Issues of AJB 47

Personalia 47

In Memorium 47

Vernon Irvin Cheadle, 1910-1995 48

Educational Opportunities 49

Funding Opportunities 49

Positions Available 50

Symposia, Conferences, Meetings 51

Book Reviews 54

Books Received 66

BSA Logo Items Available from the Business Office 68

Volume 41, Number 3: Autumn 1995 ISSN 0032-0919

Editor: Joe Leverich

Department of Biology,

Saint Louis University

3507 Laclede Ave.,

Saint Louis MO 63103-2010

Telephone: (314) 977-3903

Fax: (314) 977-3658

e-mail: leverich@sluvca.slu.edu

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

News from the Society, the Sections and the Committees

BSA Concludes August Meeting in San Diego

The annual meeting of the Botanical Society was held August 6-10 in San Diego, California, in conjunction with the AIBS meetings. All participants agreed the meeting was quite successful this year, encompassing a number of symposia and contributed paper sessions, in addition to the important business meetings of the Society and its various sections. There are a number of reports from this meeting in this issue of the PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN, and additional reports will appear in future issues. One important topic will continue to be a theme of Society activity for the months ahead: moving forward with the Botany for the Next Millennium report. This document focused discussion at the Council and Executive Committee meetings, and all the sections have been invited to become involved in the coming year.

Looking to the future, the Botanical Society will be meeting again with AIBS in August, 1996, at the University of Washington in Seattle. The 1997 meeting will be in Montreal, Canada, with ALBS and CBA/ABC. BSA will meet in 1998 with AIBS in Baltimore, Maryland, and the 1999 meeting will be held in Saint Louis, Missouri in conjunction with the International Botanical Congress.

Botany for the Next Millennium:

A Note from the President

This next year will be pivotal for the BSA as it considers the Botany for the Next Millennium (BNM) report. The BNM report is the result many individuals' hard work to assess the present and future of Botany . The report outlines the challenges Botany will face in the coming years and makes very specific recommendations for action. At our annual meeting in San Diego the BSA began to consider the report; a major task of the Executive Committee this next year will be to develop a plan for response to the BNM report recommendations. Each section of the Society has been asked to chose an area of the report and devise a plan of action. Those of you that wish to respond on an individual basis please feel free to send your comments to me or any of the executive committee members.

— Barbara A. Schaal, BSA President

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

ISSN 0032-0919

?ublished quarterly by Botanical Society of America, Inc., 1735 Neil Ave., Columbus, OH 43210

The yearly subscription rate of $15 is included in the membership dues of the Botanical Society

of America, Inc. Second class postage paid at Columbus, OH and additional mailing office.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to

Kim Hiser, Business Manager

Botanical Society of America

1735 Neil Ave.

Columbus OH 43210-1293

Phone/Fax: 614/292-3519 email: KHISER@MAGNUS.ACS.OHIO-STATE.EDU

Page 38

YOUNG BOTANISTS AWARDS - 1995

The young Botanist Award Program of the BSA recognizes the most outstanding graduating seniors in plant biology at each college or university. The achievements of the students selected for recognition were impressive both in and out of the formal classroom setting again this year. Botanists can he reassured that exceptionally motivated, talented, and interested students are pursuing plant studies across the U.S. and Canada.

The following individuals received recognition for Special Achievement as Young Botanists:

Natasha Bacheller (Tufts) Kristen McDonnell (Brown)

Matthew Aaron Booker (Purdue) Kevin Postma (Miami)

Joseph M. Craine (Ohio State) Sara Reeder (Miami)

Kathleen Lynn DeGroft (Miami) Krista Reutzel (Ohio U.)

Gordon T. Hill (James Madison) Laura Rose (Duke)

Laurie A. Krueger (U. Wisconsin, Stevens Pt.) Martha J. Sassone (UC Riverside)

Jennifer L. LaBundy (NE Missouri State) Noel K. Studer (Ohio U.)

Kristen A. Lennon (Conn. College) Mary Kathryn Whitson (U. Florida)

Laurel Leong (UC Davis) Chris Wolverton (Miami)

Carl E. Lewis (Conn. College) Sally Lizabeth Yost (Purdue) Satya Miliakal (Brown)

The following individuals received Recognition from the Young Botanists Program:

Scott Bagley (Miami) Matthew Allen Langdon (Purdue)

V. Christine Boryenace (Purdue) Brad W. Smith (Ohio U.)

Shannon Ruth Cox (Purdue) Janet Zeis (Miami) Megan Hanley (Ohio U.)

If your college or university is not represented and you have appropriate candidates, consider nominating your leading student or students (generally the top 6-8% of botany students) next year.

Each Young Botanist Awardee receives a letter of recognition and a certificate signed by the Past President. The BSA also sends letters, if requested, to the Dean of the appropriate college. A number of institutions cite the Young Botanist Award at graduation and some offer a year's membership in the Society to awardees.

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN

Editorial Committee for Volume 41

Donald S. Galitz (1995)

Dept. of Botany

North Dakota State University

Fargo NC 58103

Robert E. Wyatt (1996)

Institute of Ecology University of Georgia

Athens GA 30602

James D. Mauseth (1997)

Dept. of Botany

University of Texas

Austin TX 78713

Allison A. Snow (1998)

Dept. of Plant Biology

Ohio State University

Columbus OH 43210

Nickolas M. Waser (1999)

Dept. of Biology

University of California

Riverside CA 92521

Page 39

NEW CORRESPONDING MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY ELECTED

Two distinguished scientists were elected to Corresponding Membership in the Botanical Society of America at the Annual Business Meeting on Tuesday, August 8, in San Diego. The Corresponding Members Committee was unanimous in recommending approval for Corresponding Membership for Dr. Mary Kalin Arroyo and Dr. David Lloyd.

Mary Kalin Arroyo, Professor of Biology at the Universidad de Chile, Santiago, has become well known for research on pollination ecology, first in the rain forests of Chile and more recently in the Mediterranean ecosystems of Chile. She was elected President of the Botanical Society of Chile in 1992, and has been very active in expediting botanical research in her role as Coordinator of the Latin American Plants Sciences Network.

David Lloyd, Professor of Plant Science at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand, is one of the world's leading researchers in plant reproductive biology. Among his many imaginative contributions to the field is a redefinition of sexual function in plants. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand in 1984, and was a visiting Miller Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1990.

Botanical Society of America 1995 Dinner for All Botanists

One of the high points of the 1995 Annual Meeting was the Dinner for All Botanists on Wednesday evening, August 9, at the Town and Country Hotel in San Diego. Overflow attendance necessitated setting up additonal tables, but all the botanists and their guests were able to enjoy the wonderful San Diego hospitality.

President Horner recognized those seated at the head table, which in addition to most of the Officers of the Society included AIBS President W. Hardy Eshbaugh, AIBS Executive Director Clifford Gabriel, and Meeting Director Donna Haegele. Horner extended special tnanks to the local representative, Lisa Baird of the University of San Diego.

Following dinner, President Horner presented a number of awards and prizes to Members of the Society. These are de-tailed later In this Issue of Plant Science Bulletin. President-Elect Barbara A. Schaal was then introduced for the evening's address. After focusing the audience's attention on the Society's recent Botany for the Next Millennium report, she illustrated many of her points with work from her own lab in the genus Manihot.

The dinner was brought to a close as outgoing President Horner turned over the reins of the BSA to incoming President Schaal.

Page 40

Reports from the Committees:

Corresponding Members Committee

The Corresponding Members Committee had two vacancies to fill for 1995. The three members of the committee were unanimous in approving for Corresponding Membership Dr. Mary Kalin Arroyo and Dr. David Lloyd. The committee noted that the election of both Dr. Arroyo and Dr. Lloyd as Corresponding Members is not only recognition of their achievements but also an indication of the vitality of the field of plant reproductive ecology. [See announcement of new Corresponding Members earlier in this issue of PSB for more details. -Ed.]

—Grady L. Webster, Chair

Darbaker Prize Committee

The committee this year consisted of myself (as Chair), Peter Siver (Department of Botany, P.B. 5604, Connecticut College, New London, CT 06320), and Jeff Johansen (Department of Biology, John Carroll University, University Heights, OH 441 18). In November we sent out notices for Darbaker Prize nominations that later appeared in newletters of the Phycological Society of America and the Botanical Society of America. The committee chose Dr. Daniel Wujek (Department of Biology, Central Michigan University) to receive the Prize this year, which consisted of a monetary award and a certificate. We are currently seeking a replacement for Peter Siver, who rotates off the commit-tee this year.

—Joby Marie Chesnick, Chair

Education Committee

During the past year, the Education Committee was involved with the following projects:

1. International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). We continued our participation in this event that showcases the best scientific projects by pre-college students from all over the world. This year the fair was held in Hamilton, Ontario. BSA is a member of the organization and sponsors two Special Awards. An article on the winners will be forthcoming in PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN.

2. Coalition for Education in the Life Sciences (CELS). The Education Committee participated in the 4th annual CELS conference that was held at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. CELS is an organization comprised of representatives from various professional scientific societies. The purpose of CELS is to help unite various professional societies to see how they can impact science education from K-undergraduate.

The Education Committee set several goals for 1995-96. These include (I) working closely as a committee, communicating, sharing ideas setting priorities and completing projects, and delegating tasks as necessary; (2) continuing with ISEF and to develop a checklist of "chores" to make it easy for a person to work on this project; (3) developing a BSA Home Page; (4) discussing/determining how the committee's role/response to Botany for the Next Millennium; (5) pursuing discussions with the Coalition for Education about Environment, Food, Agriculture and Renewable Resources (CEEFAR), a coalition of 36 scientific societies that is preparing a charter to help bring educators to enhance competency of teachers and education-al materials; and (6) pursuing projects such as inviting to the annual meeting State Science Fair winners and secondary teachers from the state where the meeting is held, distributing the Careers in Botany pamphlet at the meeting of NABT and other organization, and developing a workshop to offer at meetings of NABT.

—Stephen G. Saupe, Chair

Election Committee

The Election Committee for 1995 consisted of the Past President, Secretary, and 3 members appointed by the President. This year there were elections for the offices of President and Treasurer, with three candidates standing for each. The President-Elect, with a plurality out of 463 ballots, is Dan Crawford. The Treasurer, with a plurality out of 459 ballots, is Judy Jernstedt, who is declared reelected.

Also on the ballot this year were two proposed changes to the Bylaws. The first, to modify Article 4, Sect. 1 (c) read: "The Election Committee prepares a slate of two [not three] names for each office." On the basis of only 30 ballots, it passed by a bare margin of 76% (23 approve). The second proposed change, to specify the basis for awarding the M. F. Moseley Plant Anatomy/Morphology Award, passed with 29 approvals out of 31 ballots.

—Grady L. Webster, Chair

Membership and Appraisal Committee

A new poster and recruitment brochure were designed and readied for printing. We developed a more streamline format than the one used in previous years to make it easier and quicker to read. When these recruitment materials are completed, they will be sent to our 550 membership coordinators at individual institutions.

—Jim Hancock, Chair

Page 41

Esau Award Committee

Eleven papers were submitted to be evaluated for the Katherine Esau Award. These were presented in four sessions in the section: vegetative development, structure and function, reproductive development and wood anatomy/vascular development. These presentations reflected both the diversity as well as the high quality of current research activities in structural and developmental botany. All presentations reflected considerable effort on the part of the speakers. The award was presented to Stuart F. Baum for his paper co-authored with his advisor Thomas L. Rost, from the University of California at Davis, for their paper entitled "Analysis of Arabidopsis root development." Using a combination of traditional histological techniques and two-dimensional and three-dimensional modeling of cell division, Mr. l3aum demonstrated that root apical organization is appropriately interpreted as resulting from interconnected spirals of cells arising from apical initials. The committee was particularly impressed by the insights of the investigator, his very clear and logical presentation, and his professional presentation style.

Dr. Thomas informed Mr. Baum of his selection for the award prior to the banquet. A check in the amount of $500 was sent to Mr. Baum by the treasurer of the BSA. Announcement of the award was presented in the September 1994 issue of PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN.

—Cynthia S. Jones, Chair

Moseley Award Committee

The number of papers to be judged for the Maynard F. Moseley Award in 1995 was twelve; nine from the Structural/Development Section, and three from the Paleobotanical Section, as determined by the Award Committee in conjunction with the Program Directors for the two sections. The 1995 award was $250 (non-invasive of principal).

— Ed Schneider, Chair

Pelton Award Committee

Elliot M. Mcyerowitz of the California Institute of Technology received the 1994 Jeanette Siron Pelton Award for sustained and imaginative work in the field of experimental plant morphology. No award is being made in 1995. A request for nominations for the 1996 award will be made in the next issue of PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN.

— Nancy Dengler, Chair

Reports from the Sections

Bryological and Lichenological Section

The Bryological and Lichenological Section co-sponsored the ABLS meeting in Jasper National Park, Alberta, Canada from July 29 - August 3rd, 1995. Organized by Chicita Culberson and Dale Vitt, this meeting entailed four days of field trips in the Rocky Mountains and one day of poster and paper presentation, including one symposium and 15 contributed papers. The half-day symposium, organized by Brent Mishler, was entitled "The Application of Modern Molecular Tools to Classic Bryological andLichenological Questions." The Botanical Society provided honoraria for the five invited speakers. The Bryological and Lichenological Section is sponsoring a single session with seven contributed papers at the San Diego AIBS meeting.

Jason Pass from East Tennessee State University received a $200 student travel award from the Bryological and Lichenological Section to attend and present a paper at the 1995 ALBS meeting.

The recipient of the 1994 A.J. Sharp Award for the most outstanding student presentation at the 1994 AIRS meeting was Alison Withey from Duke University. A $100 prize from the Section (plus $200 from ABLS) and complete set of The Bryologist accompanied this award.

—Karen Renzaglia, Chair

Developmental and Structural Section

The section sponsored two symposia, "The Biology and Evolution of the Gnetales" (with the Paleobotanical Section); and "Morphological and Develop-mental Mutants of Maize" (with the Genetics and the Physiological Section). The Section also sponsored a special lecture, "The lost genius of WilhelmHofineister: the origin of causal-analytical research in plant development". In addition, section sessions this year consisted of 46 contributed papers and 13 posters. The section includes 438 members.

— Judy Verbeke, Chair

Ecological Section

At the San Diego Meetings the Ecological Section sponsored three symposia. A total of 44 contributed papers in four sessions and 13 posters were present-ed. There were 17 submissions for Best Student Paper Award. The award for Best Student Paper at the 1994 meeting was presented to Andrea L. Case at the 1995 BSA banquet in San Diego. The section currently has 570 members. New officers elected for the three year period, 1996-98, are Brenda Casper, Chair; Allison Snow, Vice-Chair and Rebecca Dolan, Secretary.

— Kathleen Shea, Chair

Page 42

Genetics Section

This year in San Diego, the Genetics Section is hosting two paper sessions and a poster session (20 contributed papers and four posters). The annual Margaret A. Menzel Award for most outstanding paper presentation in the Genetics Section paper session will be awarded at the Botanical Society banquet. Scott A. Hodges won the award in Knoxville last year. The section is sponsoring a symposium entitled, "Genetic Engineering and Conservation of Rare Plant Species" addressing both potential benefits and hazards of genetic engineering in preserving and protecting our rich heritage of plant genetic diversity. The section is also co-sponsoring a symposium on "Morphological and Developmental Mutants of Maize." The Plant Genetics News-letter continues to be the mainstay of the section through which members are able to share ideas and disseminate information.

— Donald P. Hauber, Vice-Chair

Mycological Section

This is the first year for the Mycological Section. Three papers were presented. Bylaws were established and officers were elected. The section cosponsored with the Mycological Society of America a symposium on Plant and Mycorrhizal Community Dynamics and a workshop on Cladistic Analysis of Fungi.

— Kenneth J. Curry, Chair

Paleobotanical Section

The Paleobotanical Section has a program for the San Diego meetings with thirty five contributed papers presented during one and one half days. The Section is also sponsoring a symposium, "Practical and Theoretical Aspects of Incorporating Fossils in Analyses of Modern Taxonomic Groups," organized by William L. Crepet and Kevin C. Nixon, and is co-sponsoring a symposium with Structure and Development entitled "Biology and Evolution of the Gnetales." A mixer and dinner are scheduled for Mon-day evening, August 7. The Annual business meeting will be held at 4:30 PM (a change from the published time of 4:I5) on Wednesday. August 9, 1995.

The Section currently has 230 members (164 regular members, 20 emeritus regular members, 22 affiliate members, 7 emeritus affiliate members, and 17 honorary members). This is a loss of 17 members since last year.

The Bibliography of American Paleobotany for 1994, edited by Steven R. Manchester of the University of Florida, is being distributed to members at these meetings and will be sent in September to non-attending members of the section who have paid their 1995 dues and to 38 institutional subscribers. Copies will be provided for the BSA archives and the editor of PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN. Others may purchase copies for $18 each.

The International Organization of Paleobotany will be holding its periodic meeting next year in Santa Barbara, California, at about the same time as the Botanical Society meetings. It is likely that the Paleobotanical Section will vote to hold its annual meeting at the IOP meeting. As a result, there may be a reduced number of paleobotanical papers at the 1996 BSA meeting. The Section will vote on this matter at its business meeting.

— Charles P. Daghlian, Secretary-Treasurer

Phytochemical Section

The Phytochcmical section contributed to Botany for the Next Millennium, and is sponsoring its usual small contributed paper session at the 1995 meeting. The few active section members continue to explore the possibility and merits of merging with another section, but prefer to retain the Phytochemical Section, if participation continues to warrant it. Joint sponsorship of a symposium with another section has been suggested as a way to attract more attendance and participation.

— Susan S. Martin, Chair

Pteridological Section

As in previous years, the Pteridological Section continues to support the publication of the Annual Review of Pteridophyte Research now published by the International Association of Pteridologists. This year at the San Diego meeting the Pteridological Section is co-sponsoring with the American Fern Society a session of contributed papers with six papers scheduled for Mon-day and two full day field trips on Saturday and Sunday.

—David S. Conant, Secretary-Treasurer

Systematics Section

The activities of the section included the presentation of 200 papers, two symposia, and I l posters at the annual meeting in San Diego, and the compilation of data from the Botany for the Next Millennium report. As of July 1995, approximately 750 members of the BSA have affiliated with the Systematics Section, and our activities continue to be done in parallel with the American Society of Plant Taxonomists. At the annual business meeting, elections were held for Section Chair. Dr. Kathleen Kron (kronka@wfu.edu) of Wake Forest University was elected for the term 1995 to 1997. Dr. Wayne Elisens (Univ. Oklahoma) will continue as Section Secretary/Treasurer for one more year; Dr. Elisens also serves as the ASPT Program Chairman.

A proposal made by Rob Wallace to establish a student award from the Systematics Section was dis-

Page 43

cussed. The award would be made to the student (as defined by not yet having received the doctorate degree, undergraduates included) who was judged to have presented the best contributed paper in the BSA/ASPT jointly sponsored sessions at the annual meetings. Additionally, it was suggested that this student award be named the Arthur Cronquist Award, and that the winning student be presented with a certificate and a cash award of between $200 and $500 from the Section's annual allocation of $1,000 from the BSA. A general vote of support for the establishement of this award was made and approved; further details about the award, eligibility, judging, etc. will be presented in the next PLANT SCIENCE BULLEN. Dr. Richard Jensen has volunteered to assist in the development of this award; additional award committee volunteers and other suggestions are sought. Rob Wallace (rwallace@iastate.edu) will chair the student award committee; efforts will be made to have the award structure in place to present the first student award in 1996. The Section will likely be a co-sponsor for a symposium on the evolution of green plants being organized for the annual meetings in Seattle in 1996. Ideas for the implementation of the Botany for the Next Millennium report from members of the Section are sought; please contact the new Chair of the Section.

—Robert S. Wallace, Section Chair

Tropical Biology Section

This year the section has corresponded with the Association for Tropical Biology to dovetail sessions and cosponsor symposia. The meeting place in San Diego will permit greater participation by Mexican Col-leagues, but the price of the meetings may limit the same. At this August's business meeting, we will come up with a slate of candidates for section officers for elections to be held by mail this fall.

The goal of this relatively new section is to emphasize the importance of Tropical Biology in our current pursuit of the study of plants. If we are to preserve the bounty of the tropics for appreciation and potential use in the next millennium, every botanist must be aware of the need for basic research in taxonomy, ecology, morphology, anatomy, physiology, phytochemistry.— in short, every aspect of tropical plants and the organisms with which they interact.

—Suzanne Koptur, Chair

Mid-Continent Section

The Mid-Continent Section meet with the SWARM Division of AAAS in Norman, Oklahoma, May 21-25, 1995. The section held a contributed papers session. Sheryl A. Schake (Texas Tech) and Michael Zwick (Texas A&M) received outstanding graduate student paper awards. A symposium "Evolutionary mechanisms in plants: from genes to clades" was sponsored. The speakers were Timothy P. Holtsford, Robert K. Jansen, Pamela Diggle, and Jonathan F. Wendel.

A business meeting was conducted. At this meeting the members voted to revise the section's By-Laws so that the Secretary/Treasurer and Vice Secretary/Treasurer serve three-year terms staggered with the term of the Chairperson and Vice-Chairperson. Ralph Bertrand (Colorado College) and Kenneth Freiley (Univ. Central Arkansas) were elected Secretary/Treasurer and Vice-Secretary/ Treasurer, respectively.

—H. James Price, Chair

Southeastern Section

The Southeastern Section of the BSA held its 1995 annual meeting during the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association of Southeastern Biologists, 19-22 April, in Knoxville, Tennessee. At that meeting, which included nine affiliate biological societies, of the 277 and posters scheduled at least 182 directly related to Botany. The Section continued its support of "Teaching Updates in Botany" by the sponsorship of a four hour workshop on "The Use of Ceratopteris, the Rapid Cycling Fern in Teaching Plant Biology" which was conducted by Karen Renzaglia of East Tennessee State University and drew nineteen participants from eighteen different institutions. The annual business meeting of the section was during the traditional breakfast meeting with the South-ern Appalachian Botanical Society. Dr. David Hill, Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, was elected Secretary-Treasurer for the 1995-98 term. A three page newsletter was sent to all section members in March of 1995 by outgoing Secretary-Treasurer Richard Carter.

—Joe E. Winstead, Chair

Thanks for Helping!

Thanks to the following individuals for their help in selling logo items at the BSA booth at the AIBS meetings: Joe Armstrong, Don Hauber, Suzanne Koptur, Carol Baskin, Judy Jernstedt, Greg Anderson, Marsh Sundberg, Dan Crawford, Kathy Shea, Sue Martin, Lee Kass, Bob Hunt, Jack Horner, Judy Thomas, Dave Hiser, Lisa Baird and Judy Verbeke and others who did not leave their names. Due to their efforts, over $2,000 was added to the Endowment fund from sales of t-shirts, totebags, lapel pins, posters and hats. The Endowment funds help support BSA activities such as travel to international botanical congresses, the Botany for the Next Millennium project and other initiatives. All members are invited to contribute to the Endowment and to volunteer at the BSA table at future AIBS meetings.

Kim Hiser, Business Manager

Page 44

Awards and Prizes at BSA Annual Meeting

The following awards and prizes were announced on 9 August 1995, at the Dinner for All Botanists given by the Botanical Society of America (BSA) at its Annual Meeting held in San Diego, California, in conjunction with the Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Biological Sciences.

The Botanical Society of America Merit Awards

These awards are made to persons judged to have made outstanding contributions to botanical science. The first awards were made in 1956 at the 50th anniversary of the Botanical Society, and one or more have been present each year since that time. This year Merit Awards went to two botanists. Awards were presented to Isabella A. Abbott, the first Hawaiian woman to receive a Ph.D., eminent phycologist, authority on algal diversity along the California coast; and ethnobotanist, authority on traditional uses of Hawaiian plants, and to James E. Canright, scholar on the Ranales, his systematic studies of primitive angiosperm groups contributed to the understanding of flowering plant evolution and his pioneering work in palynology established the significance of the discipline for both basic and applied research.

The Maynard F. Moseley Award

This year the BSA welcomed a new student award. The Maynard F. Moseley Award was established to honor a career of dedicated teaching, scholarship and service to the furtherance of the botanical sciences. The award recognizes a student paper that best advances our understanding of the plant anatomy and/or morphology of vascular plants within an evolutionary contest. This first award was given to Susana Magallon-Puebla from the University of Chicago and Field Museum of Natural History, for her paper entitled "Floral remains of Hamamelidaceae from Campanian strata of Georgia."

The Darbaker Prize

This award is made for meritorious work in the study of microscopical algae. The recipient is selected by a Committee of the Botanical Society which bases its judgment primarily on papers published during the last two calendar years. The award this year went to Daniel Wujek for his recent work on the chrysophytes and the chlorophytic algae.

The Michael A. Cichan Award

This award established by the Botanical Society of America is named in honor of Michael A. Cichan. It was instituted to encourage work by a young researcher at the interface of structural and evolutionary botany. The award is given to a scholar for a published paper in these areas. The Michael A. Cichan award for 1995 was presented to Dr. Steven R. Manchester, University of Florida, for his paper entitled "Fruits and Seeds of the Middle Eocene Nut Beds Flora, Clamo Formation, Oregon."

The Isabel C. Cookson Paleobotanical Award

Each year the Isabel C. Cookson Award recognizes the best paper presented at the annual meeting by a student or recent Ph.D. in the Paleobotanical Section. This year the award went to Georgia L. Hoffman from the University of Alberta, for the paper entitled "A Spirodela-like plant from the Paleocene Joffre Bridge locality."

The Margaret Menzel Award

This award is given by the Genetics Section for an outstanding paper presented in the contributed papers sessions of the annual meetings. This year's award went to Kelly Gallagher for the paper entitled "Allozyme evidence for hybridization and introgression between an introduced and a putative native species of Carpobrotus (Aizoaceae)."

The Ecological Section Award

Each year the Ecological Section of the Botanical Society offers an award for the best student paper presented at the annual meetings. A judging committee evaluates each student presentation and selects a winner based on the quality of the work and the presentation. 1994's best paper was given by Andrea L. Case of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. The paper was entitled "Manipulation of grandparental temperature and parental flowering time." Co-authors were Elizabeth Lacy and Robin Hopkins.

The Distinguished Paper in Phycology Award

The Distinguished Paper in Phycology Award was initiated in 1991 to recognize the most outstanding manuscript published in the American Journal of Botany in a given year dealing with any aspect of algal research. This year's award went to Linda Graham, James Graham, William A. Russin, and Joby Chesnick for their paper "Occurrence and phylogenetic significance of glucose utilization by Charophycean algae: Glucose enhancement of growth in Coleochaete orbicularis."

The Katherine Esau Award

This award, established in 1985 with a gift from Dr. Esau, is given to the graduate student who presents the outstanding paper in developmental and structural botany at the annual meeting. This year's award went to C. John Runions from the University of Victoria for the paper entitled "Pollen scavenging in spruce and evolution of the conifer pollination drop." Co-author was John N. Owens.

(Awards continue on p. 46)

45

...more Awards from BSA Banquet

The Edgar T. Wherry Award

This award is given for the best paper presented during the contributed papers session of the Pteridological Section. This award is in honor of Dr. Wherry's many contributions to the floristics and patterns of evolution of ferns. This year's award went to Gerald Gastony and David Rollo from Indiana University for their paper entitled "Cheilanthoid fern phylogeny inferred from an enlarged database of rbch nucleotide sequences."

The George R. Cooley Award

This award is given annually by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists for the best contributed paper in plant systematics presented at the annual meeting. This year's award was given to Paul S. Manos from Duke University for the paper entitled "Evolutionary history of the southern beeches (Nothofagus): Evidence from molecules, morphology, and fossils."

The Harry Allan Gleason Award

This award is given annually by the New York Botanical Garden in recognition of an outstanding recent publication in the fields of plant taxonomy, plant ecology, or plant geography. This year the New York Botanical Garden presented two awards: one in cryptogamic botany, and one in phanerogamic botany. The first recipient was Richard H. Zander for his 1993 publication entitled "Genera of the Pottiaceae: Mosses of harsh environments." The second recipient was Peter K. Endress for his 1994 publication entitled "Diversity and evolutionary biology of tropical flowers."

The Jessie M. Greenman Award

The Jessie M. Greenman Award is presented each year by the Alumni Association of the Missouri Botanical Garden. It recognizes the paper judged best in vascular plant or bryophyte systematics based on a doctoral dissertation published during the previous year. This year's award went to Lynn Bohs for her publication "Cyphmandra (Solanaceae)" which was published as Monograph 63 of Flora Neotropica. This study was based on a Ph.D. dissertation from Harvard University under the direction of Dr. R. E. Schultes.

<left>

</left>

Commentary - Usenet Newsgroups for Botany and Systematics

Editor:

I am pleased to announce the recent creation of two Usenet newsgroups: sci.bio.botany and sci.bio.systematics. The creation of sci.bio.botany and sci.bio.systematics involved a public discussion and call for votes (CFV) via e-mail. Until recently, Usenet participants in the United States have dominated efforts to create new groups, but there are now clear signs of a rapidly emerging global community of Usenet readers, especially among biologists. This trend is evident in the distribution of responses to the CFV: 52% originated in 30 countries other than the United States.

Back in the early 1970's, when electronic mail was in its infancy, there evolved two distinct methods of sharing e-mail or news among many people. Today, these are known as electronic mailing lists and Usenet newsgroups. Since 1990, I have published in Usenet and the Internet a serial listing of these and other resources of special interest to biologists. This listing has grown into a 40-page guide (Smith 1993, 1994) that is widely used as an aid in learning how to make the most of the Internet and other electronic resources. The guide explains the basic mechanics of reading and contributing to electronic mailing lists and Usenet newsgroups.

It is my hope that many readers of PSB will want to participate in sci.bio.botany and/or sci.bio.systematics. To facilitate this, I have given brief directions (below) on how to obtain a copy of my guide.

— Una Smith

Department of Biology

Yale University

Smith, U.R. (1993) A Biologist's Guide to Internet Resources. Ver. 1.7. Available via anonymous FTP from sunsite.unc.edu in the directory pub/academic/biology/ ecology+evolution/bioguide. See the file README for details about currently available formats and foreign language translations.

Smith, U.R. (1994) A Biologist's Guide to Internet Resources. Ver. 1.8. This is an update of the section of 1.7 on electronic mailing lists. It is also available from sunsite.unc.edu.

<left>

</left>

Announcements

Forum on Mentoring Graduate Students

A special session on the mentoring of graduate students is being organized for the 1996 AIBS/BSA meetings in Seattle. We are in the early stages of planning, and the hope is to have a breakfast or lunch session, with brief oral presentations and a student-faculty panel discussion. If you or your institution has written policies or guidelines on the duties, ethics and responsibilities of mentoring graduate students, or if you would be willing to make a 10-minute presentation on how you approach this critical aspect of training the next generation of botanists, please contact either of the organizers: Darlene Southworth, Dept. of Biology, Southern Oregon State College, Ashland, OR 97520, southworth @ sosc l . sosc.osshe.edu; Judy Jernstedt, Dept. of Agronomy and Range Science, UC Davis, Davis, CA 95616, jjernstedt@ucdavis.

Science & Biodiversity Policy - Now Available from AIBS

AIBS has announced the availability of the supplement to BioScience entitled Science & BiodiversityPolicy. Compiled from speeches given at the AIBS 1994 Annual Meeting, this 96 page stand-alone supplement contains important information about the many aspects of biodiversity and public policy. Authors include Hal Mooney, Thomas Lovejoy, Jane Lubchenco, Kent E. Holsinger, Quentin D Wheeler, Monica G. Turner, Frank W. Davis, W. Franklin Harris, Lance H. Gunderson, Jerry F. Franklin, Louisa Willcox, and H. Ronald Pulliam. An excellent teaching resource, topics covered include the role of science in formulating policy decisions and the public's understanding of biodiversity. Single copies are available for $10.50; bulk orders are available at a discount. For more information about the issue contact Dr. Julie Ann Miller, 202-628-1500 x243; to order contact Genevieve Clapp. 202-628-1500 x251.

Request for Botanical Literature

The Association of Systematics Collections (ASC) is embarking on a second round of obtaining biosystematic literature for the Biodiversity Information Exchange with Cuba Project. This time, literature acquired will be distributed to institutions outside of Havana. In trying to build biodiversity information re-sources, Cuban research institutions have a great need for current and back issues of botanical journals and other ecological and biosystematic literature. To donate and for more information, please contact Elizabeth Hathway, ASC, 730 11th Street, NW, Second Floor, Washington, D.C. 20001-4521, (202) 347-2850, fax: (202) 347-0072.

Back Issues of AJB

American Journal of Botany volumes 1949 through 1994 available as a donation to an institution or individual. Recipient to pay shipping costs Contact E. Steiner, Dept. of Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1048, or e-mail: esteiner@ biology.lsa.umich.edu.

Personalia

Patricia K. Holmgren Receives Sevice Award

The Association of Systematics Collections, in recognition of her outstanding contribution to systematics collections and the field of Botany, presented its 1995 Award for Service to Patricia K. Holmgren of the New York Botanical Garden.

In its award, the ASC cited her remarkable devotion to herbaria and their use in science and society worldwide, as the leading force behind Index Herbariorum, her inspirational leadership as Director of the New York Botanical Garden Herbarium, and service on the boards of ASC and major botanical societies, her dedicated work to support and preserve endangered herbaria, her yeoman's service to the botanical community as editor par excellence, and with her husband Noel, for sharing their love for and knowledge of the Intermountain Flora with the world through their seminal botanical publications.

In Memorium

Josef Poelt, Corresponding Member

The Botanical Society was notified that Prof. Dr. Josef Poelt passed away in early June, 1995. He was affiliated with the Department of Botany, University of Graz in Austria. The number of Corresponding Members, distinguished senior scientists who live and work outside the United States, is limited to 50. Prof. Poelt first joined the Society in 1988. He was the only current Corresponding Member from Austria.

The Botanical Society has been notified that the following members have passed away:

Earlene A. Rupert of the Department of Agronomy and Soils, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina, a member since 1944.

Frederick T. Wolf of the Department of Biology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, a member since 1936.

Page 47

VERNON IRVIN CHEADLE 1910-1995

The botanical community and higher education have lost one of their strongest advocates and most distinguished citizens. Vernon Irvin Cheadle died on July 23 in Santa Barbara, California.

The botanical community and higher education have lost one of their strongest advocates and most distinguished citizens. Vernon Irvin Cheadle died on July 23 in Santa Barbara, California.

Vernon Cheadle was born in Salem, South Dakota on February 6, 1910, grew up on a farm in South Dakota, and attended South Dakota State College for one year before transferring to Miami University. He received a B.S. (magna cum laude) from Miami University in 1932, and an M.S. (1934) and a Ph.D. (1936) from Harvard University. His Ph.D. research was concerned with secondary growth in monocotyledons. His mentor at Harvard was Ralph H. Wetmore.

Dr. Cheadle joined the Department of Botany at Rhode Island State College in 1936, and served as Professor and Chairman of the department from 1942 to 1952. From 1942 to 1952, he also served as Director of the Graduate Division at Rhode Island, except for a commitment with the Navy in the Pacific Theatre of WW II from 1944 to 1946. His prodigious talent and ability as an administrator had already become evident to those around him. During that same period he was an enormously productive teacher and researcher. He continued his research on the vascular system in monocotyledons, with special emphasis on phylogcnetic specialization of the sieve tubes in the metaphloem and vessels in the metaxylem. Among other notable findings, his research revealed that, in monocotyledons, vessels appeared first in the root and later in stems, inflorescence axes, and leaves, in that order.

In 1950-51, Dr. Cheadle spent a sabbatical year at the University of California at Davis. His attraction to Davis was Katherine Esau, who shared his interest in vascular tissues, especially the phloem. During his sabbatical year at Davis, the botany department had an interim chairman, and upon his return to Rhode Island, Dr. Cheadle received an invitation to return to Davis as the department chairman there. While on sabbatical at Davis, the quality of the man shone through. The folks at Davis were impressed not only with his research, teaching, and administrative credentials, but also with his genuine interest in students and the warm response he received from students. Davis was a small institution at the time and the botany faculty, in particular, were uniquely concerned for their students. Vernon Cheadle was just right for the chairmanship.

While at Davis, Dr. Cheadle's collaboration with Dr. Esau resulted in a series of contributions on the comparative structure of secondary phloem in dicotyledons. These included a detailed investigation on the cellular organization of the secondary phloem studied primarily by an analysis of radial files of cells in serial transverse and tangential sections. In other studies, large numbers of species from many families were examined for specific features such as variations in cell wall thickness, the effect of cell division on the final length of sieve elements, and the size of sieve-plate pores. These studies were especially important in discussions of the evolutionary specialization of the phloem tissue in relation to function. In the late 1950s and early 60s, he and Dr. Esau undertook some of the first ultrastructural studies on phloem.

Dr. Cheadle served as President of the Botanical Society of America in 1961, and in 1963 he received the Merit Award of the Society. The Certificate of Merit read "for his deep and abiding interest in science, his service to biology through untiring efforts to promote scholarly teaching and research, and for his major contributions to the interpretation of the evolution of vascular tissue in the monocotyledons and of the structure of phloem in the dicotyledons." There was much more to come.

In 1962, Dr. Cheadle was appointed Chancellor of the University of California at Santa Barbara. Dr. Esau decided that she would also move to Santa Barbara so that she and Dr. Cheadle could continue their collaborative research. Although they continued to work together, Dr. Cheadle's major efforts during his 15 years as Chancellor were laying the foundation for a first-class research university. Under his leadership and vision, UCSB underwent remarkable growth and attracted a critical mass of distinguished scientists and scholars. As Chancellor, Dr. Cheadle's principal concern was students all aspects of their well-being. During his entire tenure, he held breakfast meetings (twice monthly) with student representatives at the Chancellor's residence on campus. He retired as Professor and Chancellor Emeritus in 1977.

Dr. Cheadle endured as Chancellor during the most tumultuous of times in the history of higher education in the United States. Nothing could deter him from

Page 48

achieving the goals he had set for the future ofUCSB. He is remembered today as one of the great leaders in the history of the University of California system. In 1979, the UC Board of Regents named UCSB's main administration building Vernon I. Cheadle Hall. A building could well he named also for Mary Cheadle, who has contributed so very much to UCSB. (A room in the Department of Special Collections of the University Library bears her name.) She and Vernon were an inseparable, dedicated team. They very naturally and unselfishly gave of themselves for the welfare of others.

Upon "retirement," Dr. Chcadlc returned to the laboratory full time, literally. He spent five days a week in the laboratory and often worked on weekends. He simply could not learn enough about the tracheary elements in monocotyledons: the kinds, their occurrence, and their taxonomic and phylogenetic implications. Collaborating with him on this research was Dr. Jennifer Thorsch. Most recently, they were working on the tracheary elements of the Bromeliaceae.

One of Dr. Cheadle's associates at UCSB characterized him as: "a Renaissance man, a mind-and body kind of guy." Dr. Cheadle was a track and field champion during his college years. In 1978, he was inducted into the Miami Athletic Hall of Fame. For 18 years and until recently, he competed in the Masters Track and Field Meets and held several Masters world records in the discus throw and shot-put. A distinguished botanist, educator, athlete, and human being, Vernon I. Cheadle was the personification of excellence and integrity. He was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, Phi Kappa Phi, and a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the California Academy of Science, and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Vernon Cheadle was a devoted and loving husband and father. A most caring and loyal person, he never neglected his family nor his friends, who were legion. He had an enormous, positive impact on all who knew him well, especially this writer during a very formative period in his life as he aspired to become a botanist. Dr. Cheadle expected his students to work hard and to strive for excellence. He cared, he shared, and he led by example. Vernon Cheadle never forgot his humble beginnings in South Dakota and had great respect for everyone from all walks of life. These values he also instilled in others. We are all wealthier for him having touched our lives. — Ray F. Evert

Educational Opportunities

Graduate Research Assistantships University of Hawaii

Graduate Research Assistantships (Ph.D. or M.S.). The University of Hawaii seeks outstanding candidates for its NSF Graduate Research Training assistantships in ecology, evolution and conservation biology. For application information and materials, contact Kenneth Kaneshiro (Chair) or Rosemary Gillespie (Associate Chair), CCRT, University of Hawaii, 3050 Maile Way, Gilmore 409, Honolulu, HI 96822. (808) 956 8884, e-mail: gillespi@uhunix.uhcc.hawaii.edu. Deadline: Feb. 1 1996. Assistantships commence August 1996.

Funding Opportunities

Michaux Fund Grants

The American Philosophical Society announces the 1996 competition for research grants in forest botany (specifically, dendrology), silviculture, and the history thereof. Grants range from $1,500 to ca. $5,000. Eligible expenses include travel, $65 per diem toward the cost of room and meals, and consumable supplies not available at the applicant's institution. Applicants are normally expected to have the doctorate, but proposals may be considered from graduate students who have completed all degree requirements but the dissertation. Deadline: February 1, for decision by May. When writing for application forms, briefly (100 words or less) describe the proposed research and budget. Foreign nationals must state why their research can only he carried out in the United States. No telephone requests, please. Contact: Michaux Fund Grants, American Philosophical Society, 104 S. 5th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106-3387

Bullard Fellowships in Forest Research

Each year Harvard University awards a limited number of Bullard Fellowships to individuals in biological, social, physical and political sciences to promote advanced study, research or integration of subjects pertaining to forested ecosystems. The fellow-ships, which include stipends up to $30,000, are intended to provide individuals in mid-career with an opportunity to utilize the resources and to interact with personnel in any department within Harvard University in order to develop their own scientific and professional growth. In recent years Bullard Fellows have been associated with the Harvard Forest, Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Kennedy School of Government and have worked in areas of ecology, forest management, policy and conservation. Fellowships are avail-able for periods ranging from four months to one year and can begin at any time in the year. Applications from international scientists, women and minorities are encouraged. Fellowships are not intended for graduate students or recent post-doctoral candidates. Further information may be obtained from: Committee on the Charles Bullard Fund for Forest Research, Harvard University, Harvard Forest, Petersham, MA 01366 USA. Annual deadline for applications is February 1.

Page 49

Travel/Host Grants for American Scientists

The Office for Central Europe and Eurasia of the National Research Council, the operating arm of the National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine, offers grants to individual American specialists who wish to collaborate with their colleagues from Central/Eastern Europe (CEE) and the Newly Independent States (NIS). To obtain information and application materials please contact: Office for Central Europe and Eurasia, National Re-search Council, 2101 Constitution Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20418, Telephone: 202-334-3680, Fax: 202-334-2614, E-mail: OCEE@NAS.EDU.

Positions Available

Manager of Scientific Collections University of Connecticut

The Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Connecticut seeks a full-time Collections Manager to maintain and curate collections of plants and vertebrates used in research and teaching. The principal responsibility will be to manage a herbarium collection with particular strength in the flora of New England and the Neotropics. The Collections Manager also will be responsible for collections of fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. The successful applicant will be expected to actively in-crease holdings in the herbarium through field collections and exchanges with other institutions. Other duties will include placing current specimens and new acquisitions for all collections into a computer data base, man-aging loans to and from all the collections, facilitating use of the collections by faculty and graduate students, supervising student volunteers and employees working in the collections, and carrying out other departmental duties as appropriate. Salary negotiable. Applicants should have an advanced degree (Master's or Ph.D.) in botany or a related field, experience in the management of natural history collections, knowledge of computer data-base management, and an interest in collection-based research. Please send a letter of application, curriculum vitae, reprints of relevant publications, and three Ietters of recommendation to Gregory J. Anderson, Head, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Connecticut, 75 N. Eagleville Road, Storrs, CT 06269-3043. Review of applications will begin September 15, 1995 and continue until the position is filled. We encourage applications from under-represented groups, including women, minorities, and people with disabilities.

Postdoctoral Research Associate-Molecular Phylogenetics, Montana State University

This position will research the evolution of wheat by cloning, sequencing, and conducting phylogenetic analysis of low-copy-DNA sequences from the nuclear genome. Experiments will address general aspects of molecular evolution and polyploid evolution in plants. Required: Ph.D. in Genetics, Phylogcnetics, Population Genetics, or related field. Experience in molecular biology and/or phylogenetic analysis of DNA sequence data. Preferred: A strong record of research productivity as evidenced by publication. Salary is $24,500 per year, and the position is funded for two years. Applicants should send 1) letter of application describing research activity, 2) transcripts of university work, 3) current curriculum vitae, and 4) names, ad-dresses, and telephone numbers of three references to: Luther Talbert, c/o Kathy Jennings, Dept. of Plant, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717-0312. Screening will begin October 1. ADA/AA/EO/Vet.Pref.

Plant Physiology, Stephen F. Austin State University

Tenure track position at the Assistant Professor level. Must have a Ph.D in plant physiology or plant biochemisty and be qualified to teach plant physiology, introductory botany, introductory biology and advanced courses in area of interest (ex., cell biology, ultrastructure, plant biochemisty, stress physiology, ecophysiology). Must participate in graduate program and establish a modest research program. Salary commensurate with training and experience. Review of applicants will begin immediately, with a deadline of October 9, 1995 or until position is filled. Starting date: August 1996. Applicants should request application form at address below. Send completed application, curriculum vita, transcripts, three letters of recommendation and a statement of teaching and research philosophies and career objectives to: Dr. Don A. Hay, Chairman, Department of Biology, Box 13003, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, TX 75962. (409) 468-3601. EO/AA Employer. Applications Subject to disclosure under Texas Open Records. Act.

Managing Editor, Flora of North America

Missouri Botanical Garden aggressively seeks a Managing Editor for the Flora of North America Organizational Center. Duties: FNA Managing Editor over-sees the entire scope of transforming the work of contributors and editors into the products of the FNA, participates in the application of informatics, supervises the daily work of the FNA central office (FNAC) at Missouri

Page 50

Botanical Garden, and integrates the flow of information among the off-campus participants and the FNAC. The successful candidate will also participate in the preparation and management of the budget, in fundraising, and in the reporting to the FNA Organization in general and to specific subgroups.

Organization: The FNA Managing Editor will report to the project's Convening Editor and will work closely with a newly-established Management Commit-tee. The Managing Editor will be a regular member of the Missouri Botanical Garden staff.

Requirements: An established track record in the field of systematic botany is required, including an earned doctorate in systematic botany or equivalent training, and a record of published accomplishment in floristics and/or monographic research writing and/or editing scientific literature, knowledge of botanical terminology, nomenclature, and familiarity with the protocols of keys, descriptions, maps, and ecological data. Experience in organizing complex projects and administering them, and a capacity for flexiblity are required, as are competence in writing and public speaking, and basic computer literacy.

Please submit c.v. and names and addresses of three references to Human Resource Division, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, Missouri 63166-0299. Applications accepted until position filled. Equal Opportunity Employer.

Symposia, Conferences, Meetings

Harnessing Apomixis, 25–27 September 1995

College Station Hilton Hotel and Conference Center, College Station, Texas. Invited speakers and contributed posters will cover various genetic, molecular, physiological, cytological, and evolutionary aspects of asexual seed reproduction and its application to crop improvement. Related topics in plant sexual reproduction will also be presented. Some financial support for international attendees will be available. For further information and circulars, please contact Dr. David M. Stelly, Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843-2474. Phone: (409)-845-2745, fax: (409)-862-4733, E-MAIL: monosom@rigelAamu.edu.

Engineering Plants, 1 - 4 October 1995

International Symposium on "Engineering Plants for Commercial Products/Applications", University of Kentucky, Lexington KY, USA. Co-organizers: Glenn B. Collins and Robert J. Shepherd. To be added to the conference mailing list, send your name and ad- dress to: International Symposium on Engineering Plants, c/o Conferences and Institutes, 218 Peterson Service Building, Lexington KY 40506-00005, USA. Email: monica.stoch @ukwang.uky.edu, phone: 606/ 257-3929; FAX: 606/323-1053.

42nd Annual Systematics Symposium, 6-7 October 1995

The 42nd Annual Systematics Symposium will be held October 6 and 7, 1995 at the Missouri Botanical Garden, Saint Louis Missouri. The program is entitled "A National Biological Survey." For information, contact P. Mick Richardson, Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis MO 63166-0299.

World Palm Symposium, 20-21 October 1995

The 1995 World Palm Symposium will be held October 20 and 21, 1995 at the Fairchild Tropical Garden, Miami, Florida. It will be sponsored by Fair-child Tropical Garden and The Palm Beach and Cycad Society. This will be a unique symposium featuring 13 of the top palm researchers in the world. It will be an unusual opportunity to learn about the current palm research and conservation projects being done.

There is very limited seating for this symposium and it is suggested that you register as early as possible. Registration is $80 until September 20, and $100 thereafter. Group rates are available at the Holiday Inn, 1350 South Dixie Hwy. Send registration to World Palm Symposium, 16652 Velazquez Blvd., Loxahatchce, FL 33470. For further information, call Paul Craft at (407) 793-9029 or send fax to (407) 790-0174.

International Alpine Garden Conference 5-10 Janaury 1996

The New Zealand Alpine Garden Society will host an international alpine gardening conference in Christchurch from 5-10 January, 1996. The conference will include special field trips to Mount Hutt and Arthurs Pass as well as presentations by sought after speakers. New Zealand's leading botanists and gardeners will be joined by international experts in a forum which is without precedent. The conference, "Southern Alpines '96" will focus on the alpine plants of the Southern Hemisphere - South Africa, South America, and of course Australia and New Zealand. For further information contact the Conference Secretary, Jane McArthur, 1/37 Augusta Street, Christchurch 8, New Zealand. Phone/Fax (03) 384 2170.

Page 51

8th International Lupin Conference, 11-16 May 1996

Scientists from throughout the world will be gathering May 11-16, 1996 for the 8th International Lupin Conference in the scenic Asilomar Conference Center near Monterey. The scientists convening at Asilomar in 1996 will report on a number of topics that will be of interest to scientists and growers alike—new crop development, human and animal food uses, nitrogen fixation, ecological importance, as well as the agronomic aspects of lupin.

A full agenda is planned for the conference, with three days of symposia scheduled in the mornings. Afternoons will be devoted to concurrent contributed papers and poster sessions in one of the following categories: agronomy, genetics, alkaloid chemistry, ecology, and utilization of lupin. A field trip is scheduled for Tuesday, May 14, and will include visits to field plots that demonstrate the diversity of lupin and other crops grown in California.

"California is an important gene center for native species of lupin," said Barbara Bentley, professor of Ecology at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Bentley is also president of the international Lupin Association. "Of the 190 species of lupin world-wide, 120 occur in California. This conference is an exciting opportunity to foster cross-disciplinary discussion on the prospects for lupin as a crop, as well as its role in natural systems."

The registration fee is $250 if received by April 10, 1996. Housing at Asilomar starts at $48 per day, depending on the level of luxury and number of occupants per room. The housing fee includes all standard meals at Asilomar. This conference is being organized by the International Lupin Association and is co-sponsored by the Department of Agronomy and Range Science at the University of California, Davis and the North American Lupin Association. This is the first time the conference has been held in the United States. For further information or registration materials, write to Conference & Event Services (lupin), University of California, Davis, CA 95616-8766, USA or contact by phone at (916) 757-3331, FAX at (916-757-7943 or by e-mail at jcbarnes@ucdavis.edu. Please provide full name and address with appropriate postal codes, phone numbers, country and city codes and e-mail addresses.

Association of Systematics Collections Annual Meeting, 19-22 May 1996

"Global Genetic Resources: Access, Owner-ship and Intellectual Property Rights" will be the topic of the 1996 Annual meeting of the Association of Systematics Collections, held in conjunction with the Beltsville Symposium at the Beltsville, Md., Agricultural Re-search Center, May 19-22, 1996. Scientists worldwide will explore issues related to ownership of and access to genetic resources and biological specimens around the world. Among the subjects discussed will he access to collecting and collections; the international distribution of germplasm; the exchange of scientific information on biodiversity; and current policies and trends related to ownership and exchange of genetic and biological re-sources. International experts will address subjects related to biological resources for comparative taxonomic study, including food and fiber crops, insects that are natural enemies of crop pests and microorganisms like fungi, yeasts and parasites.

The Association of Systematics Collections will also sponsor a 1 1/2-day, presymposium-workshop on public affairs advocacy (May 18-19). For more information about the presymposium-workshop call Elaine Hoagland (202) 347-2850; fax (202) 347-0072; e-mail mnhasO01@sivm.si.edu. For more information about the symposium contact Amy Y. Rossman (301) 504-5364; fax (301) 504-5810; e-mail amy@fungi.arsgrin.gov.

Ecological Competitiveness in Migrations, 9-12 June 1996

That is the subject of a proposed symposium at the 6th North American Paleontological Convention, June 9-12, 1996, in Washington, D.C. Some aspects of the topic might be: Which plant and animal taxa have undergone long-distance migration and under what conditions? What properties did they possess that allowed them to migrate? How well did they do after they arrived at their destination; in that connection, what has been the ' durability of the migrants in their new region compared with their post-migration durability in their original region? Do new immigrant taxa become established by competitive replacement or by filling empty niches? Is there any correlation between the success of immigrant taxa and their inherent abilities to evolve?

The First Circular of NACP-96 has been distributed; if you didn't get one, write, call, or fax me and I will send you one. The Second Circular will be mailed this Fall, so I will be glad to put you on the mailing list or you can reply directly to the NACP-96 converners using the form in the First Circular. However, I would be pleased to hear from you if you are interested in giving a paper at the symposium described here. I hope to get a good mixture of plant and animal papers, based on material of various ages. It seems that enough is known about long-distance migrations of taxa in the distant past, and the profound effect some of them have had on evolution and changes in flora or fauna after their arrival, so that next year at NACP would be a good place and time to explore these questions. Contact: Norm Frederiksen-U.S. Geological Survey, mail stop 970, Reston, VA 22096; phone 703-648-5277; fax 703-648-5420.

Page 52

NAFBW - XlVth Meeting, 16-20 June 1996

The XIVth Meeting of the North American Forest Biology Workshop will be held from 16-20 June, 1996, at Laval University, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. The theme will be "Forest Management Impacts on Ecosystem Processes." Contact: Ms. Dominique Houde, Agora Communication. 2600 boul. Laurier (#2680), Sainte-Foy (Qc) G1 V 4M6. Tel. (418) 658-6755. FAX. (418) 658-8850. Voluntary workshops, contact: Pierre Bernier, CFS. Tel. (418) 648-4524. More information at WWW site: http://forestgeomat.for.ulaval.ca/

In Vitro Biology, 22-26 June 1996

The 1996 World Congress on In Vitro Biology carries the title "Biotechnology: From Fundamental Concepts to Reality." It is scheduled to meet at the San Francisco Marriott, San Francisco, California, June 22-26, 1996. The abstract deadline is January 12, 1996. For further information, contact meeting coordinator Tiffany McMillan, tel. 410-992-0946, fax 410-992-0949.

IOPC-V, 30 June - 5 July 1996

The Fifth International Organization of Paleobotany Conference (IOPC-V) will take place on the campus of the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB), Santa Barbara, California, USA, from 30 June through 5 July 1996. The theme of the conference is floristic evolution and biogeographic interchange through geologic time. The program will include eight morning symposia and four afternoons of contributed papers and posters, followed by two optional 7-day field trips. The first circular, containing a detailed description and registration information, is available from Bruce H. Tiffney, Department of Geological Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106. Fax: 805-893-2314, e-mail: tiffney@magic.ucsb.edu.

Extant and Fossil Charophytes, 7-13 July 1996

The 2nd International Symposium on extant and fossil Charophytes (Charales) at Madison, Wisconsin, will cover a wide scope of topics dealing with extant and fossil forms and fossil/extant relationships; a session will be devoted to the evolutionary position and taxonomic status of the Charophyta. For more information, please contact Dr. Linda Graham (Department of Botany, University of Wisconsin - Madison, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706-1381, fax 608-262-7509, e-mail graham@macc.wisc.edu) or Dr. Monique Feist (Colloque Charophytes, Laboratoire de Paleobotanique, UM2, 34095 Montpellier cedex 05, France, fax 33.67.04.20.32, e-mail mofeist@isem.univ-montp2.fr).

Natural Science Collections Symposium 20-24 August 1996

The Geological Conservation Unit and the Department of Earth Sciences of the University of Cam-bridge are organizing the Second International Symposium and World Congress on the Preservation of Natural History Collections to occur August 20-24, 1996 at St. Johns College, Cambridge, U.K. The theme will be "Natural Science Collections - A Resource for the Future"

The second Congress will continue the work of the first Congress by bringing leading figures in industry, research, education and natural science museums together to discuss future developments and a joint cooperative approach towards the challenges presented by the preservation of natural science collections, and to look at the practical aspects of putting the strategies in place. The Congress is co-sponsored by several collections support organizations, including the Association of Systematics Collections and the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections.

For more information, please contact: Chris Collins, Natural Sciences Congress '96, Geological conservation Unit, Department of Earth Sciences, Downing Street, Cambridge, CB 2 3EQ, United Kingdom, tel: (0223) 62522, fax: (0223) 60779.

2nd Crop Science Congress, 17-23 November 1996

The second International Crop Science Congress (ICSC) is scheduled 17 to 23 Nov. 1996 at the Hotel Ashok, Chanakyapuri, in New Delhi, India. In-creasing population and declining assets of natural re-sources constitute a major challenge to global food security. This concern has led congress organizers to choose the theme: Crop Productivity and Sustainability: Shaping the Future. Three categories of presentations at the congress will be plenary, symposia, and posters. In addition, working groups will deliberate on topics of specific interests for framing policy documents. Popular lectures will also be organized on some evenings. Registration is US$300 by 1 June 1996, $400 thereafter. Accompanying members cost $100 each, as does a student registration without proceedings. For more information contact: Prof. S.K. Sinha, Secretary-General, 2nd ICSC, National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi - 110 012, INDIA, Fax No.: 91-11-5753678, Telephone Nos.: 91-11-5753677 / 5753713.

<left>

Page 53

Book Reviews

In this Issue:

Ecological:

p. 54 Biological Diversity, The Coexistence of Species on Changing Environments M. A. Huston (1994) — A. M. Ellison

Economic Botany:

p. 56 Ethnobotany and the Search for New Drugs G.T. Prance, et al., eds. (1994) — M.J. Schlessman

p. 57 The Chocolate Tree: A Natural History of Cacao A. M. Young. (1994) — N. A. Harriman

Historical:

p. 58 Historical Perspectives in Plant Science K. J. Frey, ed. (1994) — S. Hammer

p. 59 The Correspondence of Charles Darwin. Vol. 9. 1861. F. Burkhardt, et al., eds. (1994) — V.B. Smocovitis

Physiological:

p. 60 A Whole Plant Perspective on Carbon-Nitrogen Interactions J. Roy & E. Garniers, eds. (1994) — M. Holbrook

Paleobotanical:

p. 61 The Enigma of Angiosperm Origins N.F. Hughes (1994) — D. Cantrill

Structural/Developmental:

p. 63 Plant Cell Biology: A Practical Approach N. Harris and K.J. Oparka, eds. (1994) — J. Z. Kiss

Systematics:

p. 63 The Palms of the Amazon. Andrew Henderson (1995) — P. Berry

p. 64 The Dicotyledonae of Ohio. Part 2. T.S. Cooperrider (1995) - D. J. Hicks

Biological Diversity: The Coexistence of Species on Changing Landscapes. Michael A. Huston. 1994. ISBN 0-521-36093-5 (cloth U.S. $100.00); 0-521-36930-4 (paper, U.S. $34.95), 681 pp. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge CB2 1 RP, UK — Nearly a quarter-century ago, Robert MacArthur predicted that ecologists would erect "a two-or three-way classification of organisms and their geometrical and temporal environments...[t]he future principles of the ecology of coexistence will then be of the form `for organisms of type A, in environments of structure B, such and such relations will hold— (Mac-Arthur 1972). Huston's magnum opus is a simultaneously enthralling and frustrating attempt to simplify and coherently explain the maintenance of species coexistence. Following MacArthur's lead, Huston erects a two-way classification of species: first, according to their ecological function, and second, grouped within functional types. Species diversity of a community then simply equals the total number of functional types multiplied by the average number of species per functional type. Two broad functional types encompass all others: 'structural' species that give form and shape to habitats (e.g., canopy trees, reef-forming corals); and 'interstitial' species that live within habitats created by structural species (including the structural species themselves).

Other functional types (e.g., trophic species) can fit within the structural-interstitial framework, and are useful in identifying more clearly within-habitat patterns of diversity. The problem of explaining species diversity then is reduced to one of explaining how different functional types coexist, and how many functionally analogous species coexist within a functional type. Historically, the latter problem has proven more difficult than the former, and thus explanation for the coexistence of functionally-equivalent species (e.g., plants) receives more attention in Biological Diversity than explanations for the coexistence of different functional types.

Although high-visibility efforts to protect and preserve the planet's biodiversity focus routinely on charismatic megafauna, it long has been appreciated that "the extraordinary diversity of the terrestrial fauna...is clearly due largely to the diversity provided by terrestrial plants...[o]n the whole, the problem [why are there so many kinds of animals] remains, but in the new form: why are there so many kinds of plants" (Hutchinson 1959). The bulk of this book, therefore, focuses on explaining patterns of plant species diversity. For any given system, Huston identifies the appropriate spatial and temporal scale at which to examine species diversity, because "a mowed lawn that is a homogeneous salad to a grazing sheep is a complex, heterogeneous universe

Page 54

to a small, flightless insect" (p. 94). By focusing attention on appropriate scales of observation, Huston illustrates clearly the confusion inherent in many other published models that address the maintenance of species diversity within habitats (e.g., Connell and Orias 1964, Connell 1978) or across successional sequences (re-viewed by Connell and Slatyer 1977).

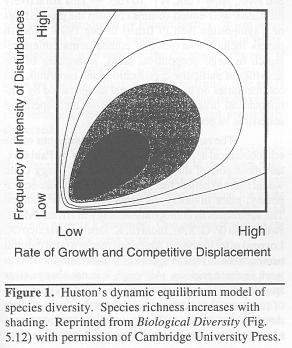

Huston's environmental templet is based on a dynamic equilibrium engendered by varying growth rates of individual species, intensity of interspecific competition, and frequency and intensity of disturbance (Fig. 1). In essence, this book is a symphonic expansion on the themes first elaborated by Huston in 1979, and the theoretical core of the book (c. 4-10) extends this model spatially from the gene to the landscape and temporally to encompass the full range of successional dynamics. As a listener is enchanted by a fine musical composition, the reader of Biological Diversity is captivated by the simplicity of the model, the overt soundness of the conclusions, and the clarity of the writing,

The punch line of the book is that species diversity is highest where productivity, likelihood of competitive displacement, and frequency or intensity of disturbance are lowest. Dozens of case studies (c. 11-14) support this pattern: examples are drawn from the speciose floras of Mediterranean climates; Amazonian centers of endemism for plants, birds, and butterflies; the high invasibility of North American habitats and low invasibility of Eurasian habitats; marine habitats ranging from the abyssal depths through coral reefs to the rocky intertidal; and fire-dependent savannas. The denouement occurs in the penultimate chapter. Huston convincingly argues that in tropical wet forests, where plant species diversity reaches its apogee, productivity and disturbance frequency are lower than they are in temperate forests. This assertion may surprise most of the book's readers, but Huston reaches this conclusion by scaling plant production rates and disturbance frequency by length of growing season.

<left>